Chris Hillman on the Flying Burrito Brothers, Gram Parsons and the End of the Sixties

Chris Hillman couldn’t have chosen a better song title for this excerpted chapter from his upcoming memoir, Time Between — out November 17th via BMG. The chapter, which covers the end of the Sixties, is called “Sin City,” a song off the Flying Burrito Brothers’ 1969 debut, In the Gilded Palace of Sin.

Below, Hillman recounts the founding of the Burrito Brothers, his relationship with bandmate Gram Parsons and more, but casts it against the tumultuous backdrop of 1969, including the Manson murders and Altamont — tragedies that, in 2020, still resonate in harrowing ways.

“You reflect on it, and you go, ‘What’s different?’” Hillman tells IndieLand of the two eras. “There’s still some major DNA flaws in the human condition… that weird, dark violent thing that we all have and we all try to keep secured and quiet in our psyches.”

The “Sin City” chapter isn’t all doom and gloom, though. It picks up in late 1968, when Hillman, although only 24, was already a seasoned veteran by rock & roll standards. He’d put in a shift with the California bluegrass band the Hillmen (also known as the Golden State Boys) and made history with the Byrds. But as the decade neared its end, Hillman says he and his long-time musical partner, Roger McGuinn, were “looking at everything like we were old men.” They wanted to try something new, and Parsons’ help, they cut a classic album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, that reintroduced country music into the contemporary rock landscape.

Sweetheart, released August 1968, would be Hillman’s last album with the Byrds, but he and Parsons would continue to carry the country-rock mantle on In the Gilded Palace of Sin, released February 1969. Musically, country rock wasn’t a huge leap for Hillman. He had his bluegrass background and the Byrds had long-flirted with country before Sweetheart. But Parsons was instrumental in helping the Byrds and Burritos actualize this new style. In both conversation and book, Hillman is frank about Parsons’ brilliance, as well as his struggles with drugs and alcohol (Parsons died of an overdose in 1973 at 26).

“He could charm the gold out of your teeth,” Hillman says; but he’s adamant Parsons ultimately suffered from a lack of professionalism (in Time Between, Hillman ties this directly to Parsons’ trust fund). What Parsons had, though, was the ambition, talent and country music know-how to match Hillman’s desire to embrace country when it wasn’t exactly “cool” and many of their peers remained skeptical.

“I remember David Crosby telling me how he couldn’t stand the steel guitar,” Hillman recalls. “And I’m trying to tell him, ‘You like sitar? The steel guitar has a sliding scale, too.’ Then, within two years, he’s got Jerry Garcia playing [steel] on ‘Teach Your Children’ — but that’s David. I love him. Stubborn. Fight me to the death. But eventually, ‘Oh no, steel’s cool, I got it on the CSN record.’”

Neither Sweetheart nor Gilded Palace were huge sales successes, but their impact was immediate as country-rock took off in the Seventies. Hillman remembers Glenn Frey watching the Burritos obsessively at the Troubador, and puts it plainly: “When we handed the ball off to the Eagles, they ran it in for 10 touchdowns.”

Decades later, both Sweetheart and Gilded Palace remain touchstones — timeless in song and sound, but also in that borderline tragic way, where the stories and themes feel like they could’ve been plucked out of yesterday. On “Sin City,” the song, Hillman and Parsons weave together vignettes of late-Sixties tumult that still feel strikingly familiar. The chorus’ closing couplet — “On the 31st floor a gold plated door/Won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain” — was inspired by a crooked business manager Hillman worked with in the Byrds, but it captures the righteous indignation gross inequality continues to inspire in 2020.

On the phone with IndieLand, Hillman stops himself before ruminating too long on the persistent wickedness of the human condition and finds a somewhat more hopeful note: “I hope we can all play live again. I hope it doesn’t get to a point where we can’t.”

Just a few weeks ago, Hillman sat in with his Desert Rose Band bandmates John Jorgenson and Herb Pedersen and their bluegrass group at a drive-in concert in Ventura, California. After a lifetime in rock & roll, it managed to be one of the most surreal experiences of Hillman’s career.

“I hope that’s not my last gig because I’d finish with people honking their horns!” He laughs. “That was the applause. I was like, ‘This cannot be my last show on this earth!’”

Chapter Ten

Sin City

Just before leaving The Byrds I had sold my house in Topanga Canyon and bought fifty-five acres of beautiful pristine land in northern New Mexico, near the town of Amalia. The Sangre de Cristo River ran through most of the property and the land was part of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range. I had hopes of someday building a little ranch house there but, for now, music was my priority. I rented a three-bedroom ranch house on De Soto Avenue in Reseda, down in the San Fernando Valley. After we made peace, Gram moved in as my roommate in the fall of 1968. In some ways, it was like the odd couple. I serious and focused, with a disciplined work ethic, while Gram was charismatic and completely disorganized. I wanted to make great music; Gram wanted to be a star. Despite our differences, it was the start of a period that I will always look back on fondly. Gram and I shared a similar warped sense of humor and a bond over our mutual love for country music. Not many people in our world thought country was particularly cool at the time, but we both understood its simple beauty.

We also both had a shared sadness. Gram’s father, like mine, had taken his own life when Gram was just about to start his teenage years. His extended family was something to behold. Though Gram came from money, the rampant alcoholism, infidelity, and backstabbing was like something out of an over-the-top Southern Gothic novel. During our time together, Gram would receive at least fifty thousand dollars a year from the family estate, which I think ultimately did him more harm than good. I didn’t have a trust fund like Gram had, but we had a connection. It’s not a topic we spoke much about, but there’s something about facing the loss of a parent at a young age that leaves a mark on you. Neither one of us could have articulated it at the time, but there was a dull mix of anger and sadness that perhaps we recognized in one another on a subconscious level. Whatever it was, we had a real connection, and for a time, we were like brothers.

I usually woke up early in those days and, one morning, I got up and started writing a song: “This old town’s filled with sin, it’ll swallow you in / If you’ve got some money to burn….” I sketched out a couple of verses and a chorus and decided I’d better get Gram out of bed to see if he thought there was something to the idea. He woke up, grabbed a cup of coffee, and added a second verse that concluded with the strange lines, “’Cause we’ve got our recruits and our green mohair suits / So please show your ID at the door.” I wasn’t sure where the old boy was going with that line, but after I came up with the last verse about Bobby Kennedy (“A friend came around, tried to clean up this town”), it all came together.

Built on a foundation of country music and Southern Baptist gospel, each verse was a little vignette about the culture of 1968. From Vietnam to Bobby Kennedy’s assassination to California’s seismic shifts, each section was wrapped around the chorus, “This old earthquake’s gonna leave me in the poor house / It seems like this whole town’s insane / On the thirty-first floor, a gold-plated door / Won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain.” Larry Spector actually lived behind a gold-plated door in a condo on the thirty-first floor of a building on the Sunset Strip, so he provided the inspiration for “Sin City.” At least he gave me something after robbing me blind.

Gram and I finished the song in about thirty-five minutes. He was really on his game during that time and we inspired each other in what soon became our daily songwriting sessions. In a two-week period, we wrote “Sin City,” “Devil in Disguise,” “Juanita,” and “Wheels”— some of the best collaborations either of us were ever involved with. We could practically finish one another’s thoughts while writing or singing. Gram and I were very different people, but we made a good team. The timing was right, as we were both looking for our next musical outlet.

When Roger and I hired Gram and made the Sweetheart of the Rodeo album, it was never intended as a permanent change of direction for The Byrds. Roger and I always viewed it as a one-off Byrds album in country music, but it was a genre I wanted to continue to explore. Traditional bluegrass music was my first love, and from that first day at Bill Smith’s house in 1961, that music had only become more ingrained in me as a player, singer, and songwriter. Since Gram and I shared a common vision to bring real country music to a rock audience with a hip sensibility, we agreed it would make sense for us to join forces and carry on from where Sweetheart left off. With that common vision, we had forged an instant partnership. We just needed a band and a record deal.

Gram knew a bass player named Chris Ethridge who he liked, which was fine with me. After playing bass in The Byrds for several years, I was eager to return to playing guitar in the new lineup, which would give me the chance to expand on both acoustic and electric. Ethridge was from Meridian, Mississippi, and was a very soulful, slow-talking southern gentleman who moved to the West coast to work in Johnny Rivers’ band. He eventually started doing session work alongside Leon Russell, Delaney Bramlett, and other musically gifted transplants. Chris was a great R&B musician, and what he played worked very well with what Gram and I were planning.

After Chris came on board, we identified our next suspect. “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow previously sat in with The Byrds a few times and was one of the strangest steel guitar players I’d ever heard—plus, one of the more interesting people I ever crossed paths with. Sneaky’s other line of work was stop-motion animation, which he excelled at. He worked on shows like The Outer Limits, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, and Gumby, while also playing clubs with Smokey Rogers and the Western Caravan. It was Smokey who gave him the name Sneaky Pete. Considering he was several years older than me, Sneaky could very well have been working with Smokey at his Bostonia Ballroom the day I met Tex Ritter when playing there with the Squirrel Barkers back when I was a teenager. Pete played single-neck steel, as opposed to the double-neck that was the choice of most steel guitarists. He used a strange tuning and had a unique tone that made him a brilliant player. Sneaky could be absolutely orchestral in his approach. Other times he could be coming at you from a whacked-out Spike Jones solar system. Most steel players are very precise in their playing because of the complexity of the instrument, but Sneaky threw out all the rules and came at it from a different angle. He was loose with the steel, sometimes not even bothering to tune it until halfway into a set. And that’s what made him perfect for us.

With Chris and Sneaky in the fold, we were on our way to becoming the consummate “outlaw band.” Gram and I discussed a few ideas about what to call our new project. The Alabama Sheiks came in among the top contenders. I liked the name a lot, but it screamed “blues band,” so I lobbied strongly for one of the other options. That’s when we officially became The Flying Burrito Brothers. For me, especially because it was reminiscent of The Notorious Byrd Brothers album title, I decided it would fit us perfectly.

The Flying Burrito Brothers. You couldn’t have assembled a finer bunch of criminals! The players, the band name, and the songs we were writing were the perfect ingredients for something either truly grand or totally insane. Over the next year, we’d drift back and forth between the two, but at that point, with the puzzle pieces of the band mostly in place, it was time to find that record deal. My former neighbor in Topanga Canyon, Tom Wilkes, was the Art Director at A&M Records — the label created by Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss. Tom was aware that I had left The Byrds and thought A&M would be a great place for my new venture. Although Warner Bros. was interested, we ended up signing with A&M. We were the only country act on the label, and I don’t think Jerry Moss or Herb Albert knew what to expect. They based their decision to sign us on the success I had as a founding member of The Byrds. It’s possible they didn’t even hear any of our music before agreeing to sign us.

My new attorney, Rosalie Morton, began the negotiations. She was a wonderful lawyer and the perfect fit for the Burritos. With her leopard-print briefcase, she took on A&M’s legal team with full force. We were doing quite well until the subject of our song publishing came up. I’d already given away my Byrds publishing to Tickner and Dickson for pennies and thought I’d learned my lesson. During my last year with the band, Roger, David and I had enough sense to form our own publishing company, McHillby Music. Gram and I should have just left it to Rosalie to negotiate our deal with A&M, but we went to the meeting for some unknown reason. Not being businessmen, we grew bored and impatient. Wanting to get out the door and get home, we agreed to let A&M’s publishing company, Irving Music, acquire half ownership of our songs. So stupid and short-sighted on my part. Rosalie was furious that we undermined her tactic of getting A&M to negotiate a recording contract with no publishing component. Her last words to us that day were, “You idiots will regret this the rest of your lives.” So true.

In late 1968, Gram, Chris, Sneaky, and I began recording our debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, at the A&M studios, which were housed in the former Charlie Chaplin film studio complex. Larry Marks and Henry Lewy produced and engineered the sessions. Henry’s true love was jazz, but he was open to working with the Burritos and our unusual musical blend. Larry had a better understanding of who we were, and really liked the songs we were bringing into the project. Along with the material Gram and I had written, Chris Ethridge came up with two beautiful songs that Gram helped him finish in the studio: “Hot Burrito 1” and “Hot Burrito 2.” Terrible titles, but fantastic tunes—possibly the best two lead vocals ever recorded by Gram, who poured every ounce of soul into those performances. Truly magical. Years later, Elvis Costello recorded “Hot Burrito 2” and wisely changed the title to “I’m Your Toy.” Overall, the album was really good on a performance level, but sonically, it wasn’t quite there.

The one thing we seemed to have problems with at first was keeping a drummer. We went through three or four different guys during the making of that first record. But, other than that, we kept our circle tight-knit. We were focused on making a great album, and there wasn’t much of a party atmosphere in the studio at all. The only “outside” performer to appear was David Crosby, who came in to add his high harmony to the Chips Moman/Dan Penn classic “Do Right Woman.” Despite the fact that Roger and I had fired him from The Byrds a year earlier, I always considered David a friend and a true talent.

With our A&M deal in place and our album completed, it was time to fine tune our stage presentation. Growing up watching the country music shows broadcast live out of Los Angeles in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, I was always drawn to the clothes the performers wore. Their rhinestones and exaggerated embroidery made for an unforgettably multidimensional musical and visual experience. There were two main western tailors in LA back then: Nathan Turk and Nudie Cohn. I think Turk may have been around before Nudie, but each possessed his own individual style. Eventually, the striking “Nudie suits” became even better known than Turk’s creations and—with the advance money from our new recording and publishing deals freshly in hand—Gram and I decided to recruit Nudie to outfit the group. To me, real country music included rhinestone suits, so I was really excited the day that Sneaky, Chris, Gram, and I drove over to Nudie’s shop on Lankershim Boulevard in North Hollywood to order our own.

Every band member’s true personality shone through with his own signature design. Manuel Cuevas, who was Nudie’s son-in-law at the time, helped with the designs and did all the tailoring. Manuel remains a dear friend, as does his former assistant, Jaime Castandea, who continues to design and create wonderful stage clothes for me to this day. Sneaky, who loved dinosaurs, ordered an image of a pterodactyl on the front of his black velvet top. For whatever reason, he wanted a pullover with no buttons or pockets, very baggy sleeves, and a crew neck collar — plus big, wide, baggy pants. A strange man, but I loved the guy. Chris Ethridge opted for a long southern-style coat, all white with red and yellow roses on the coat and pants. His classy look reminded me of a modern-day version of something out of Gone with the Wind. Gram had the vision that fit him perfectly: a white suit with a short jacket, on which was embroidered marijuana leaves and pills. Two naked ladies, sort of like you would see on the mud flaps of a truck, were embroidered on the lapels. On the back of Gram’s coat was a huge red Latino-style cross that tied in with the flames on his pants. Me, I was all over the place with my design. I couldn’t quite settle on one look, so I somehow included all manner of strange embroidered pictures—from a huge sun with a face like an Aztec god on the back, to peacocks on each side of my jacket, to the Greek god Poseidon on my sleeves, and red flames running down the legs of my pants.

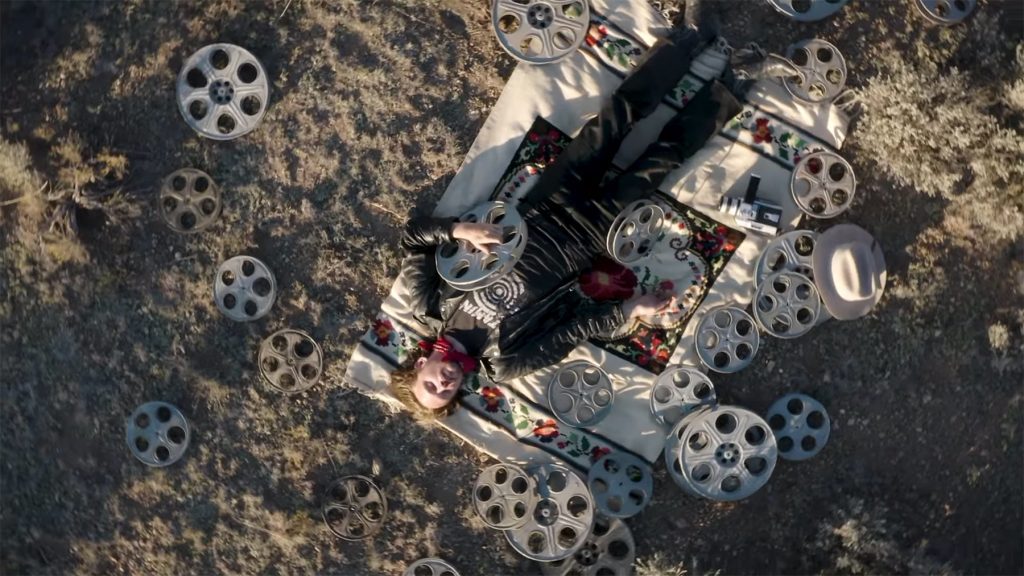

Barry Feinstein, another member of The Byrds’ extended family, photographed the cover for The Gilded Palace of Sin. Barry had shot the cover of the first Byrds album in 1965 and had attempted to shoot our ill-fated music video on the beach in Malibu. After staying up all night, we drove out to the desert, arriving at dawn. We were feeling ragged, but it actually made for a great shoot. With two beautiful models in tow and a worn-out shack in the background, the title and the look of the album suggested all kinds of devious play. It was a great cover and will always be one of my favorites.

A&M was supportive of the album and planned a preview concert at their studios. All their employees, along with other music business people from around town, were invited to our “stepping out party,” which they dubbed “the Burrito Barn Dance.” Of course, if we were going to introduce ourselves to the world, we needed to settle on a permanent drummer. Who better than my old brother from The Byrds, Michael Clarke, who had recently returned from his self-imposed exile in Hawaii? He’d been playing with Doug Dillard and Gene Clark in The Dillard & Clark Expedition, a group that also included Bernie Leadon at that time. With the group on hiatus after a particularly disastrous performance at the Troubadour, Michael was happy to join the Burritos. The event was quite a set-up, with the label having set the stage for an unbelievable party. We shined brightly in our rhinestones, but, unfortunately, we played poorly that night. Gram was wasted, and we were way too loud and completely disorganized. I remember coming off stage and knowing that we’d dropped the ball big time.

The Gilded Palace of Sin was released in February of 1969, and A&M planned our first promotional tour across the country. We hired Frank Blanco and Robert Firks to handle the equipment. Frank, who grew up in the barrio in East LA, and Robert, recently paroled from San Quentin prison, were ex-paratroopers who were a bit older and more seasoned that the rest of us. Phil Kaufman signed on as our road manager. Phil had previously worked for The IndieLands as a personal assistant — or their “executive nanny” as he referred to himself — while they were in LA Keith Richards introduced Phil to Gram, which is how Phil ended up in our orbit. I found these new characters interesting, to say the least. They proved to be loyal and always dedicated to the band members’ protection.

Gram Parsons was so smooth he could charm anyone — man, woman, or child — out of the gold in their teeth. I think he developed this gift as a survival mechanism, growing up in a Southern family of eccentric characters whose love of money and deceitful ways were right out of a Tennessee Williams story. Gram went to work convincing A&M to send us by train on this, our first tour of the Midwest and East Coast. I was to blame in the political maneuvering too. I loved trains, and I was on the Santa Fe Super Chief to Albuquerque on a regular basis whenever I had a little time to get away. It’s truly amazing the label eventually relented and actually agreed to send us that way. Phil Kaufman booked the tickets from Union Station in Los Angeles to Chicago — with stops in Albuquerque, Dodge City, and all manner of interesting places.

When the day came, we had our big send-off from Union Station, with friends waving as if they were saying goodbye to the troops heading off to fight the Great War. A&M sent their head of publicity, Michael Vosse, along with his credit card, to chaperone us, which we certainly needed. We were assigned our own Pullman sleeper car on the train and, with Michael and Gram along, trouble was always brewing. We passed the time on the two-day train ride to Chicago with lots of poker games and all manner of hedonistic pursuits. Touring by train was totally crazy and way too expensive, but we figured the label was paying for everything, so why worry about it? It wasn’t until later that we wised up and realized they were paying for everything with our money.

We finally rolled into Chicago on an early morning and prepared to play our first show that night. Most people didn’t know who we were, other than our past association with The Byrds, but, after struggling through “The Burrito Barn Dance” debacle, we began finding our footing. There were some off nights, but, musically, it turned out to be a strong tour. Gram was at his best during that first year with the Burritos, and sometimes I would just sit back and shake my head in wonder. He was so funny and bright, and nothing seemed beyond his reach. Rhinestone suits! A train tour! Turbans!

Turbans? Yes, turbans — the kind worn by Sikhs or suspect magicians. Gram was out shopping one day in Philadelphia and happened upon a store that sold turbans. He quickly bought a handful of choice models for the band and brought them back to the hotel. That night, those of us who dared wore our brand-new turbans on stage, along with our Nudie suits. I even had a blue one to match my blue suit. I felt like the 1950s R&B star Chuck Willis. It wasn’t until later in my life that the great record producer Jerry Wexler explained to me why black performers sometimes wore turbans in the old days. It was a way for African Americans to try to pass as East Indian during the era of legal segregation and blatant racial intolerance in the deep South.

One of the more memorable stops on the train tour was at a club called the Boston Tea Party where we were booked on the same bill as The Byrds. It was wild being there with Roger, Michael, Gram, Clarence White, and Gene Parsons. On the final night of shows, our bands played together. That night has since become legendary, but at the time it was just a fun and mildly chaotic attempt to make some music together. For me, it was just nice to revisit with old friends. Our lives and music were already intertwined — as they would remain for many decades into the future.

A couple of months before leaving on the train tour, Gram and I had moved from the house in Reseda to yet another ranch-style home in Nicholas Canyon, just above Hollywood. We had left that house just prior to our departure from Union Station, so when the tour was over, we staggered back to LA to the new house that Phil found for us at the end of Beverly Glen Boulevard. Mike, Gram, and I moved into Burrito Manor, which was decorated with all sorts of strange furniture that Phil and his band of minions managed to purloin along the way. We started working steady gigs at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood on Monday nights and at the Topanga Corral in Topanga Canyon on Tuesday nights, and you never knew who might follow us home after the gigs. Given my two roommates, there was always a steady stream of strange people and suspect women wandering through our house almost every night. Living with Michael and Gram was like living with a couple of animals. I actually went so far as to padlock my bedroom door while living with those guys.

Somehow, during the chaos of the train tour, Gram and I managed to find time to write another semi-gospel song called “The Train Song.” I already mentioned Gram’s knack for pulling off whatever hijinks he could think of, but he did it again when he cooked up the idea of hiring R&B pioneers Larry Williams and Johnny “Guitar” Watson to produce that record as the Burritos’ next single. Larry was best known for his songs “Dizzy, Miss Lizzy” and “Boney Maroni” (with the memorable line, “skinny as a stick of macaroni”), while Johnny was known for his signature song “Gangster of Love.” It was an idea only Parsons could come up with.

When the day arrived, we were all standing in the parking lot of A&M’s studios when a gleaming red Cadillac convertible pulled up with Larry Williams behind the wheel and Johnny “Guitar” Watson riding shotgun. They looked like a couple of characters straight from Central Casting. Larry had his initials emblazoned across his jumpsuit, which of course was bright red to match his Caddy. Johnny had on the coolest straw pork pie hat with a wide black band. Now, these guys were cool. Before the engine had even stopped, Larry was out of that car, clapping his hands. “Watson,” he shouted, “let’s make us a hit record!” In addition to our dynamic production duo, we brought in Leon Russell and Clarence White to play with the rest of the band.

Once we got settled into the studio and started working out the parts, Gram pulled out a big bag of cocaine. Johnny and Larry scoped out Parsons and started working their game: “Watson,” Larry exclaimed, “I believe this is a hit.” Johnny fired back, “You know it is!” Gram was soaking up the compliments when Michael whispered to me, “Does Parsons even know they’re just playing him for his drugs?” Chris Ethridge, being an R&B bass player born and raised in Mississippi, gave me a wink from across the room. He knew the score, too. It was a strange session to say the least, but in the end we wound up with a genuine Flying Burrito Brothers record that sounded a little like Spike Jones and his band. What it definitely was not was a hit, despite what Mr. Williams had so loudly earlier proclaimed in the A&M parking lot.

The first half of 1969 was like one never-ending party, but then the vibe suddenly changed. We were still living at Burrito Manor in August when the Manson murders happened. The free-flowing culture of trust disappeared in the blink of an eye. It was like the entire city went under lock and key. People were frightened to the point of not leaving their homes at night, and it suddenly seemed crazy to have unknown people coming and going from your house. It was later discovered that one of the Manson family’s intended targets was Terry Melcher, who produced the first two Byrds albums. Terry and Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys had gotten professionally entangled with Manson, who was an aspiring singer and songwriter. When they realized he wasn’t very good and attempted to sever ties, Manson became belligerent. It was shortly after that when Terry moved from his house, which was subsequently rented to Roman Polanski and his wife Sharon Tate — the home where the Manson murders happened. Rumors circulated that Manson targeted the place to seek revenge on Terry, and Terry himself went into hiding for a while.

Before the murders were solved, police were following every lead they could. Michael and I had a good friend from our Byrds days named Charles Tacot, an older guy who ran with Dickson and a lot of the Hollywood crowd. Charles, who’d been a small arms instructor in the Marines in his younger days, was a tough, no-nonsense kind of guy you could count on to watch out for you. After the murders, I opened up the Los Angeles Times one day and saw Charles’s name as someone they were interested in talking to. One of the victims was famed hairstylist Jay Sebring, and there was some kind of conflict between Charles and Jay. On top of worrying about the random people who’d been coming and going, we were now also convinced that the cops might burst down the door of Burrito Manor, looking for Tacot, and drag us all away. It sounds paranoid now, but it’s hard to describe the mood across the city in those dark days.

I decided it was time to move immediately — if not sooner. I found a house north of Malibu that Gram and I could rent for six months, so we moved out and closed up the Manor for good. I was the one who’d signed the lease on Burrito Manor, which came back to bite me two years later when I was stuck with the bill for unpaid damages done by my roommates. It was a few thousand dollars, so I just paid it and vowed that I would never live with either of those lovable idiots again. No question the original lineup of The Flying Burrito Brothers was the weirdest, craziest, and funniest bunch of characters I was ever involved with, but the fun of it all was starting to run its course in the late summer of 1969.

By the time Gram and I relocated, things were changing quickly. The other side of Malibu was too far from the action for Gram, so he was in and out, rarely ever staying there. We wrote “High Fashion Queen” and a few other songs together, but we definitely weren’t productively collaborating like we were before the first album. I had no idea where Gram was coming from anymore. I poured what energy I still had into protecting the music and the band while Gram, always the charmer, was more of a hustler. He was brash and assertive and sought to advance his career by networking and ingratiating himself into the right social circles. But he was starting to trade off his career aspirations for a more hedonistic lifestyle. We both had the drive to succeed but with a very different methodology when it came to execution. It just wasn’t that important to me to see and be seen, but as Gram was drawn into the trappings of Hollywood excess, I could feel him slipping away. He was drifting into dark territory, and his fascination with the party scene chipped away at the tight musical brotherhood we’d established just a few months before. It increasingly seemed that Gram cared more about fame than about the music.

Nobody held more sway over Gram than Keith Richards. If The IndieLands were around, Gram was like their eager puppy dog. He was determined to be in their presence, and it didn’t matter what other commitments might fall by the wayside. One night we were booked at a show in El Monte, a Los Angeles County suburb. On the day of the performance, I couldn’t find Parsons anywhere. Searching for Gram was becoming a daily chore, but I knew the Stones were in town cutting tracks for their next album, so I had a hunch where I’d find him. I drove to the studio, Sunset Sound, and explained why I was there. Gram didn’t want to leave until, finally, Mick Jagger walked over and said, “Gram, Chris is here to pick you up; you have a show tonight and we’re busy working.” What Mick was really saying was, “You have a responsibility to your band and your fans, and we don’t really need you here while we’re recording.” What a moment. Mick Jagger giving Gram Parsons a lesson in social and professional responsibility! Though Keith and Gram were tight, I had a feeling Mick never had much warmth in his heart for Gram. But Gram wanted to be Mick Jagger, so Mick managed to get through to him with a message I’d not been successful at communicating. I was grateful for Jagger’s words, but I sensed the end was in sight.

Despite the triumph of getting Gram to the show, it still turned out to be a strange night. We played fine, but headed home afterward while our roadies Frank and Robert packed up the equipment. A bunch of gangbangers jumped them and tried to steal our gear, but they managed to survive. Robert later told me that Frankie saved his life that day. Frank was all of five-foot-five, but he was an ex-gang member himself and a guy you wouldn’t want to mess with. I’m pretty sure the guys who caused the problem had to be helped back to their respective homes at the end of the confrontation. Frank and Robert were incredibly loyal friends who stuck with me even after the Burritos.

Though there were some good shows in 1969, in all honesty, the original incarnation of the Burritos probably started going downhill after the first tour. The concept was better conceived than executed and, unfortunately, lackluster performances were a common occurrence in that band as it became clear that Parsons was more interested in getting wasted than getting his job done. I would say maybe only every fifth or sixth show was passable, and it was killing me to go out and give audiences a sloppy performance. I felt I had reached a high mark as a musician singing and playing on The Byrds’ “Eight Miles High” and “So You Want to be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star,” but I was no longer hitting the standard I’d set for myself.

I loved working with Gram in those first months, but he simply grew more and more undisciplined. Sadly, he just couldn’t consistently deliver on our promise. He had natural stage presence, but I firmly believe that the greatest hindrance to Gram’s development as an artist was his steady stream of trust fund payments. He never had to suffer in his quest for a career in music, while everyone else had to learn how to scratch out a living while building a strong following. Gram had the drive, but he didn’t have the hunger. Despite generally strong material, we were too often lazy and weak in our execution. And Gram’s financial situation was a huge contributor to his downfall.

When it came time to start planning for another album, we were unprepared. We didn’t have a strong batch of new songs, and we’d lost Chris Ethridge who, citing family problems, returned to Mississippi. Phil Kaufman wasn’t the right guy to manage the band, and I often found myself having to be the adult in the room to keep everyone on track. By the fall of 1969, Phil was out, too, and I brought in the old team of Dickson and Tickner to help guide the Burritos. Sure, I’d had my differences with them during my time in The Byrds, but at least they had some experience in the music business.

With Chris Ethridge gone, we needed to bring in a new band member who could handle the chaos. I decided to return to playing bass, as I’d done as a Byrd, and recruited my old friend Bernie Leadon to play guitar. Bernie had left Dillard & Clark at the same time Michael departed, and he’d been playing in a group called The Corvettes, backing up Linda Ronstadt. Bernie was a fantastic singer and musician, and I was thrilled when he decided to switch gears and join us. With Gram losing focus, I knew Bernie would be a lifesaver in the vocal and instrumental departments.

Despite all the changes, the odds were stacked against us in terms of material. We were really desperate to come up with something for that second album. Generally, the recording process was draining, as Gram routinely showed up late, loaded, disengaged, or some combination thereof. Even with the challenges, however, there were still some memorable moments in the studio. Frank Blanco’s mother brought in (and acted as translator for) a Norteño accordion player named Leopoldo Carbajal to add a bit of spice to Bernie and Gram’s original song “Man in the Fog.” I enjoyed recording a couple of other things for those sessions, including “Older Guys” and “Down in the Churchyard,” but, overall, we weren’t anywhere near the groove or unique vibe we’d come up with for The Gilded Palace of Sin. The songs just weren’t there.

Needing outside material to round out the sessions, Gram convinced Mick and Keith to let the Burritos record “Wild Horses” even though they’d not yet released their own version. I think they’d sent a tape of it to try to get Sneaky to overdub a steel part, but when Gram heard it, he wanted us to cut it. The song didn’t work for me at all. It was depressing, maudlin, melodramatic, and did not fit what we were doing on the second album. At that point, I just didn’t care. I was starting to lose all interest in the band, so I just went along with it.

As it was becoming harder to maintain much enthusiasm for the Burritos, the Stones asked us to perform at their upcoming free concert to be held in December of 1969 at the Altamont Speedway in Northern California. I wasn’t sold on the idea, mainly because there wasn’t a lot of information about the event and because we’d be traveling there on our own dime. I finally gave in, and off we went. We flew to San Francisco and rented a car to head to the show.

It was a dark day. Clouds obscured the sky, and there was a thick, haunting presence in the air. We were involved in a car accident on the way to the gig and, when we finally arrived, it was complete chaos. It looked like a war zone. We quickly learned that the Oakland Hell’s Angels were in charge of security. The Angels were in an agitated state of chemical enhancement that made them overbearing, violent, and confrontational. They were flat-out scary and had already been punching and kicking anyone who happened to cross their path. When Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane jumped off the stage in the middle of his band’s set to try to take care of some problem involving one of the Angels, he was hit in the head and knocked out.

Frankie and Robert backed our equipment van up near the stage, and we prepared to do our set. As I made my way up the steps, I saw that Crosby, Stills & Nash looked to be making a quick exit after playing a few songs. As I was heading up, Crosby was coming down. He paused and looked me in the eye. “Be careful,” he warned. “This is a little strange.” A little strange? I walked up and was greeted by two burly Hell’s Angels. One of them barked, “Where do you think you’re going?” I had my Fender bass in my hand. Where did he think I was going? Not something I would say to these guys in their present condition. Feeling like a monk explaining to two Vikings that it wouldn’t be a good idea to sack and plunder the monastery, I finally managed to convince the two gentlemen stopping me at the stage that I was going up to perform.

The Flying Burrito Brothers played a good show. We managed to calm everyone down a bit, and there were no problems during our set. As we exited the stage, however, we found a very large naked man being severely beaten by a couple of the Hell’s Angels. He was out of his mind on drugs and had no clue what was happening or why. As soon as the Angels found something more interesting to go after, we pulled this guy into our van and told him to stay put until we could find someone to help him. The minute our backs were turned, he escaped from the van and proceeded to get the Angels’ attention again. They were immediately back on the attack. This was turning into an unbelievable nightmare. It was like a living Hieronymus Bosch painting unfolding before my eyes.

I gathered my belongings and — along with Sneaky, Dickson, and our friend Jet Thomas — beat a hasty retreat toward the car. Gram took off with the Stones, and I didn’t know where Bernie and Mike had ended up. It wasn’t until 2010 that Bernie told me what happened to them. The two of them got a ride back to the Sausalito Inn with our friends Toni Basil and Annie Marshall. The hotel was seventy miles from the speedway, which tells you something about how well planned the whole thing was. Mike didn’t even have a room, but he was able to talk the desk clerk out of the key to Gram’s room, where they stayed that night. By the time they finally made it to the hotel, Sneaky, Jet Thomas, Dickson, and I were on the way to the airport. We heard the horrible news on the radio that a young man had been stabbed to death by someone in the Hell’s Angels right in front of the stage.

Altamont was a far cry from the Monterey Pop Festival, which was just two and a half years prior. That’s when everyone got along, with very little security, for a nice, peaceful weekend. With the darkness descending around Altamont, it was almost predestined to end in tragedy. The promise of peace and love that had marked the 1960s was now a shattered dream. The decade wasn’t fading out with a whimper, but with a very evil and abrupt end.

© 2020 by Chris Hillman, Bar None Music, Inc. Courtesy of BMG.