Drummer Joe Vitale on His 50-Year Saga With CSNY, Joe Walsh, the Eagles, and John Lennon

IndieLand interview series Unknown Legends features long-form conversations between senior writer Andy Greene and veteran musicians who have toured and recorded alongside icons for years, if not decades. All are renowned in the business, but some are less well known to the general public. Here, these artists tell their complete stories, giving an up close look at life on music’s A list. This edition features drummer and songwriter Joe Vitale.

Veteran drummer Joe Vitale was asleep for the night when Bob Dylan’s June 2020 interview with The New York Times went online, but a friend phoned him to say he had to wake up and read it at once. “I said, ‘Man, I can read it in the morning,’” he recalls. “I woke up later and read it and was like, ‘Damn! I wish that I had read that in the middle of the night!’”

Midway through the interview, historian Douglas Brinkley asked Dylan about his favorite Eagles songs. “‘New Kid in Town,’ ‘Life in the Fast Lane,’ ‘Pretty Maids All in a Row,’” said Dylan. “That could be one of the best songs ever.”

Back in 1976, Vitale co-wrote “Pretty Maids All in A Row” with Joe Walsh, his longtime close friend and collaborator. “Coming from Bob Dylan, it doesn’t get any better than that,” says Vitale. “I called Joe immediately. And he goes, ‘I know what you’re calling about.’ I said, ‘This is so cool, Joe.’ He was excited too. He thought that was really cool. I printed out that article and framed it.”

Walsh has been playing with Walsh steadily for the past 50 years, but it’s just one part of his incredible musical legacy that also includes tours with Crosby, Stills, and Nash, Buffalo Springfield, the Stills-Young Band, Peter Frampton, Ted Nugent, the Eagles, and sessions with everyone from John Lennon and John Entwistle to Bill Wyman, Ringo Starr, and Eric Carmen.

We phoned up Vitale at his job in Canton, Ohio, to hear stories from his epic career. (We were just able to scratch the surface, so check out his book Backstage Pass for even more.)

Have you always lived in Canton?

I was born here. Briefly lived in Florida and briefly lived in Colorado, but I came back home.

I want to go back and talk about your life. When did you first get interested in playing music?

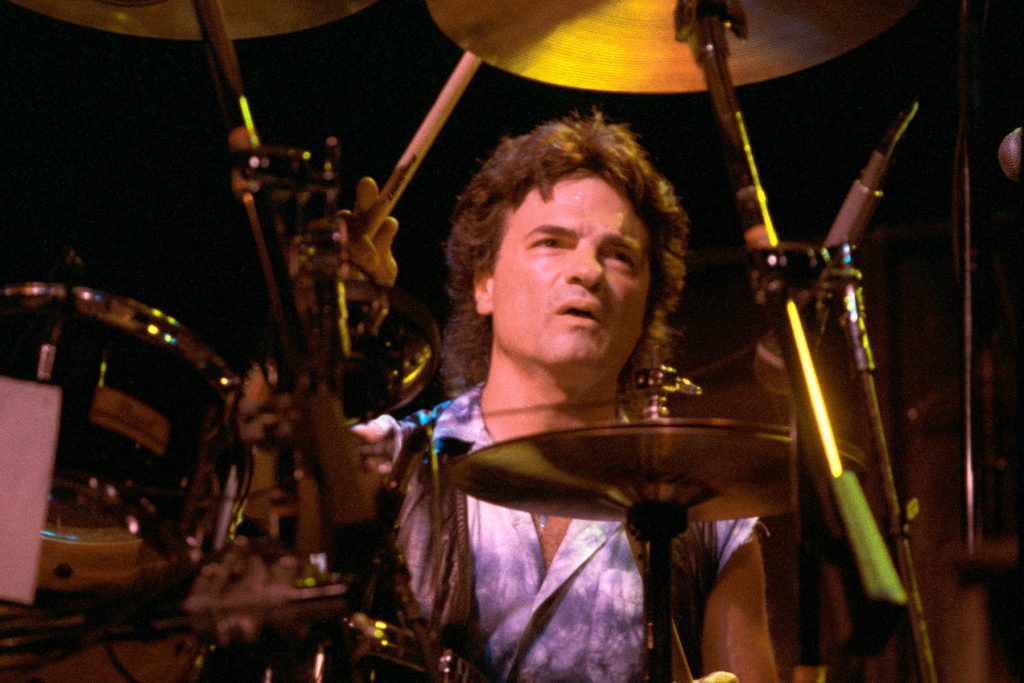

Well, father was a musician. My brother was a musician. My uncles were musicians. We were surrounded my music all the time. I was always pounding on my mom’s pots and pans. My dad said, “Guess what? You’re going to be a drummer.” I loved playing drums back then.

I started taking lessons when I was six. My father, being a musician, really knew a lot of the local teachers. I was really blessed. I had some incredible teachers. We grew up pretty poor. My dad was a barber, so we worked out a deal where he gave haircuts to the drum teacher and they traded off, haircuts for drum lessons.

Who were your music heroes back then?

My father was a jazz musician, so I was surrounded by jazz. I was listening to Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa and all those guys. That lasted a long time. In the Sixties, I started listening to rock & roll. I’m sure you heard this from everyone my age, but once the Beatles played Ed Sullivan it changed our lives and we were big Ringo fans.

Who did you get into as the Sixties went on?

Keith Moon and, of course, John Bonham. One of our favorite drummers that a lot of people don’t talk about, and we all wanted to be him, was Dino Danelli from the Rascals. Dino was so cool. He was a great drummer, but his whole stage act and whole thing was just cool. He was flipping sticks and he just had this cool attitude on his face. I finally got a chance to meet him later in life and that was very exciting.

When did you arrive at Kent State?

I went to Kent State in 1969. That’s where I met Joe Walsh. He was at Kent State as well.

Tell me your first memory of ever seeing him.

I actually saw the James Gang down in Canton in 1968. Jeez, Joe was only 21 or something. I heard about this hot-shot guitar player, so I went over to an amusement park that had a ballroom. They played a gig there and I went. The band was amazing. I met him there, but he didn’t remember me.

When I moved to Kent, he was there with his band. I looked him up, saw his show, and told him I already met him, but he didn’t remember. Anyway, I was in a bunch of different bands in Kent and he was in the James Gang. There was a lot of work in Kent for musicians. That is why a lot of us moved there. We were working five or six nights a week in rock & roll clubs. It was a college town, so we always had an audience. We were working pretty steady.

We were always talking about putting something together one day, but the James Gang were doing really well. They were doing national tours already. But we still talked about some day getting together.

Did you know Chrissie Hynde? She was on campus back then.

I knew Chrissie real well. She used to come see us play at the clubs. She was just a teenager then. Her brother Terry Hynde still lives in Kent. He’s a sax player and they have a blues band. They are still together from the Sixties.

Was your first big tour after college with Ted Nugent?

Yeah. I was playing at one of the clubs in Kent. Ted heard about Kent because it was a pretty big music town. Ted came down to Kent one night looking around for musicians. He was putting a new band together. He came into the club one night and I guess he liked what I was doing. I got a call from him a couple of days later and he invited me up to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to audition for his band. It worked out pretty good and I started playing for Ted Nugent and the Amboy Dukes.

So much attention is paid to his personality and politics that people often overlook the fact that he’s a great guitar player.

Yeah. He’s a great guitar player. He also wasn’t very political back then. He’s always been, even back when I played with him, pretty anti-drugs and anti-alcohol. He was pretty strait-laced and not very political. A lot of people when they think of him, they go right to that area of what his life is about. They do forget that he’s a really good guitar player.

How was he as a bandleader?

He was fun. Detroit had a personality. The rock & rollers from Detroit had a great personality. For some reason, they were kind of rowdy and kind of fun and just really heavy-duty rockers. That was a little different than what we had grown up with in Ohio. He was really rocking and rolling. We had a good time.

How long did your stint in his group last?

I was with him for six months. What happened was, one of the shows we did in Florida we opened for the James Gang. After the show, Joe said, “Let’s hang. Come over to my room.” We knew each other for a few years then. He said that he was going to do something different and he was going to put a new band together and he wanted me to play drums in it. I was like, “Tremendous. This is fantastic.”

Ted was really sweet about it. He was so nice. He gave us his blessing and said, “Listen, you guys should be in a band together.” He was really nice about it. And so I left Ted’s band in October 1971. January of 1972, I moved too Colorado to play with Joe. That launched a 50-year career with Joe.

How did Joe want Barnstorm to be different than the James Gang?

He wanted more of a band thing. In other words, in the James Gang, Joe did a lot of everything. He was the lead singer, lead guitar player, wrote most of everything. He was main presence and that’s a lot of pressure on an individual, to be the guy that everyone is coming to see. He wanted to be in a band. He’s a real band guy. There’s a difference. There are solo artists out there and that’s what they want to do. They’re the boss and the focus is on them. Joe is more shy than that onstage. He rocks out, but he likes the whole band thing.

His goal was in starting the band was that he wanted other people to write songs and sing, whatever. We all participated. We had a good four- or five-year run. Then I stayed with Joe after Barnstorm broke up. I still work with him.

You wrote “Rocky Mountain Way” with Joe and the rest of the guys on the first record. Can you tell me about putting that song together?

Yeah. In 1971, Duane Allman died and Joe was a big fan. He loved Duane Allman and Duane was a terrific slide-guitar player. When Duane died, Joe started playing slide. He never played slide until then. He may have messed around, but he wasn’t serious about it until then.

He picked up a slide and started messing with it. It’s a pretty difficult animal, a different instrument, but Joe is an amazing guitar player and he picked it up quickly and got really good, real fast. Today, he’s one of the greatest slide players in the world.

What happened is we were one song shy on the Smoker [You Drink, the Player You Get] album. We needed one more song based on the contract. Our producer Bill Szymczyk said, “Why don’t you guys write something to show off Joe’s new slide-guitar talent?” We said, “Oh, perfect.”

We wrote this little thing called “Rocky Mountain Way,” which was a slow blues shuffle in E. What more of a perfect song to show off slide guitar? It was just an extra song we needed, one more song for the contract. Contracts say you got to have so many songs per album.

It sounded really good. It was actually take one when we cut it. It was so good that we didn’t try to beat it. Then we were done with the album. Little did we know, that became Joe’s flagship song of his whole career. I mean, he had “Funk #49” with the James Gang and “Walk Away.” After that, there were other hits, of course.

Every time we recorded, we took every song seriously. But this one was more, “We owe them one more song, let’s have a little fun with it, some slow blues.” We were in Colorado, so Joe wrote about the Rocky Mountains. It was one of those fun, little things. It turns out to be a classic classic-rock song. We got BMI Awards for millions of airplay. It’s a classic song.

How did Barnstorm morph into a Joe Walsh solo project? What happened to the concept of a band?

We were trying to build the Barnstorm name, but that takes time. It wasn’t “Joe Walsh” and he already had a name with the James Gang. People knew who he was. Management and the record company one day were like, “You know what? We need to call this …” and I get what they were doing. It was now Joe Walsh. It went from Barnstorm to Joe Walsh and Barnstorm. Then we changed the personnel and it became Joe Walsh.

Management and the record companies are looking at things you can market. When you market a band, you gotta use everything you can. The name Joe Walsh, that was the ticket. Seeing that on a marquee brought in more people, more tickets were sold. We were cool with it. I didn’t care. We actually got bigger when we went to that. [Laughs]

How did you feel when he joined the Eagles?

By then, I had started with Peter Frampton and Crosby, Stills, and Nash. I thought it was a great move by the Eagles, a terrific move. The Eagles were always a great band. Joe stepped it up. Instead of country, they became country-rock. It was a perfect marriage with Joe and them.

I was playing with a couple of big bands by then, but we never had a thing where one guy goes one way and the other goes another way. We were always talking and writing and doing different things. We wrote songs for his next album, But Seriously, Folks …, that had “Life’s Been Good” on it. That was after Hotel California.

He was busy with the Eagles, but then the Eagles would take a break and Joe was a busybody. He’d get off the road with the Eagles and call me and be like, “Let’s go into the studio and make another record. Then we’re going to tour. Then I’ll go back to the Eagles.”

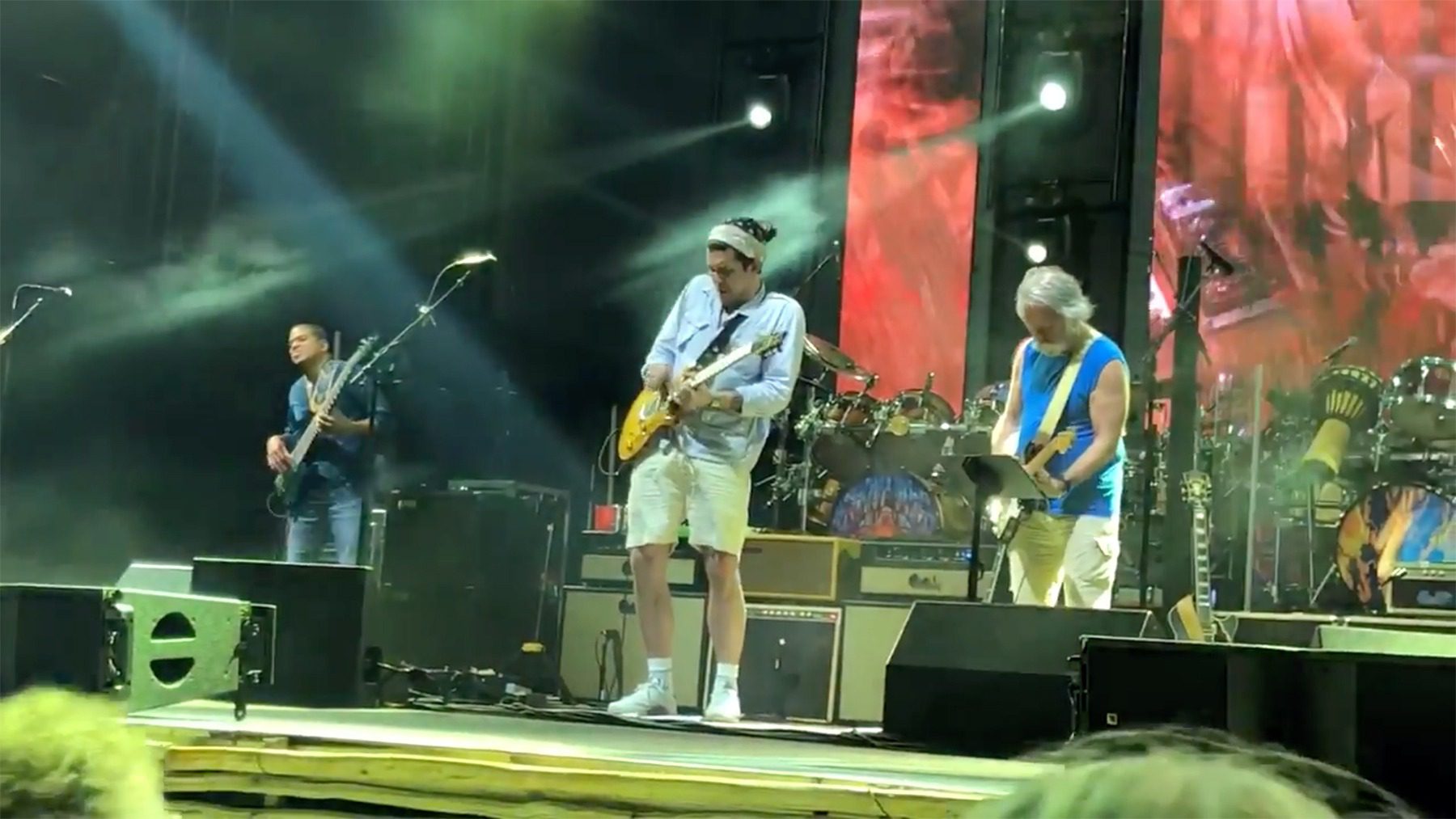

We were working all the time, just bouncing back and first. He’d go back and forth from the Eagles and I’d go to Crosby, Stills, and Nash or whatever. Then we’d get together and make more record. Then he brought me into the Eagles band. They were doing a lot of Joe Walsh music on tour. He wanted me to play drums because I played drums on the records. Also, I was able to give Don Henley a break when he’d go out and sing out front. He still does that to this day. That was fun. I did the Long Run tour with them. It was about two years.

To back up a bit, tell me about writing “Pretty Maids All in a Row” with Joe.

Like anything, Joe called me and said, “I’m working on this song.” He had this cool, little verse and he said, “Hey, why don’t you help me finish this song?” They had already started working on Hotel California and Joe wanted to get a song on there. He was finishing it up and didn’t quite have it.

At first, I didn’t know it was possibly going on an album for the Eagles. We were just writing. Glenn Frey told me a long time ago that they were sold on the song once we finished it and got the chorus. I wrote the chorus. Once that was done, they really put their vocal magic to it. It came out really good. We were really, really happy with it.

You have a songwriting credit on an album that sold 10s of millions of copies. It’s one of the biggest albums ever. I’m guessing you made some decent money from that.

Well, you know, I was just a writer on one song. What happens is that initially when an album is released and it goes sky-high on sales, you get a big check. Through the years, it dwindles way down. But I always say, if you’re going to write a song, try to write one on Hotel California. [Laughs] Either that or The Wall or the White Album by the Beatles. I actually wish I could have written some stuff with Peter [Frampton] for the live album [Frampton Comes Alive!]. He’d already recorded that when I joined him.

The Eagles are a famously precise band on stage. They want the songs to sound just like they do on the records. Was that challenging for you when you joined them for the Long Run tour?

It’s challenging in the sense that sometimes it’s harder to play the same exact thing every night than it is being a musician where you just jam. When you’re playing and not having to deal with an arrangement, just having fun, you aren’t even thinking, “OK, what’s the drum fill coming up on ‘Take It Easy’?’”

But you know what? I really appreciated that. People pay a lot of money to see an Eagles show. They get a great show and nobody ever goes home disappointed. I don’t know if they ever had a bad review. I never read one. Their live show is just incredible. It’s impeccable. Joe warned me about that. He said, “Listen, no jamming. Play the parts and play them every night. Play it like it’s your first time you’ve ever played it.” I said, “No problem. I get it.”

That tour was famously tense. Did you pick up on any conflicts they were having in the band at that time?

You know, I really didn’t. They had that blowout they showed in the Eagles documentary. The way Glenn explained it was exactly what happened. I was there. They had a blowout with Felder. That is what happened. I think it had been brewing for a while. I think it was the old straw the broke the camel’s back. It finally came to a head [that night in Long Beach.]

It was really sad. I spent two years with one of the greatest rock & roll bands in the world. We’re playing stadiums and all these great big places and all of a sudden, “We’re done now.” [Laughs] “Great, thanks a lot.” Now I’m just one of the sidemen. But man … I was really happy to see that they got back together even though it took 14 years. And thank God they did. That was too good of a band to just stop.

To go back in time a bit, tell me about jamming in the studio with John Lennon and Ringo Starr in 1974. That must have been the thrill of your life.

The thrill of a life. I was in L.A. working with Joe. We got a call from John Stronach, who had engineered some stuff with Joe. John called one night and said, “Do you guys want to come down to the Record Plant and jam with John Lennon?” We went, “Get out of here! Are you kidding?” He went, “No, I’m serious. Do you guys want to come down? He’s got all these musicians coming in. He’s going to test-run some material.” I said, “Whaaat?” Joe looked at me, I looked at him and I said, “Let’s go.”

It was amazing. There was a lot of security just to get in the building. When we got in the room, it was no big deal. Everyone was just standing around, talking. It was in Studio D, the big room at the Record Plant. John was playing piano and some guitar. He was running through some ideas and just sort of test-running it. Before he goes in and records a real record, he test-runs a lot of the material, which is really wise. A lot of bands test-run on a live performance before they even record it just to see how the audience feels.

Who was there that night?

Jeez, everybody was there. Ronnie Wood was in there and Klaus Voorman, Ringo, Jim Keltner, Nicky Hopkins. I can’t even remember all the rest, but we’re in there with all these big-timers and we’re like, “This is so cool.”

We strayed in there and this thing lasted several weeks. We’d go in there every Sunday night around midnight and we’d leave around 5 a.m. This is before cell phones. They said, “Please, no cameras. Don’t tell anybody. Keep this to yourselves.” We did. We did this for two or three weekends and then I guess somebody leaked it out and the fourth Sunday it was 5 a.m., we open the door to leave the studio and there were like 5,000 people in the parking lot.

That was the end of it. We were so pissed. We were really having fun. It was really just a beautiful camaraderie with musicians. We weren’t trying to be in a band with John Lennon. We were just hanging out with him and he was such a great guy. He just wanted to play music with musicians.

Was this for Walls and Bridges?

Yes. Some of the ideas we worked on were “Going Down on Love,” ‘What You Got,” and “Surprise, Surprise (Sweet Bird of Paradox).” Remember, these weren’t completed songs. They were just ideas. He’d take a little bit of a verse and the chords, do a little verse and a feel on the verse. We’d jam that a little bit.

Again, it was just a jam night. But if you close your eyes and open your eyes and see who was in the room, you’d freak out. It was like every rock & roll star you ever loved and they are all in there playing music. Everybody was so cool. Nobody was weird or anything like that. That’s why we were so pissed when it ended.

How did you wind up in the world of Crosby, Stills, and Nash?

Well, I met Stephen Stills in 1973. He lived in Colorado and he came up to Caribou Ranch where we were finishing the song “Rocky Mountain Way.” Stephen came to the studio because he lived in Colorado. He knew Joe, but I had never met him. He came to visit Joe and wanted to sit and listen. He heard what I was doing and he talked to me afterwards and said he really liked what I was doing. He said, “Someday, let’s play together.” I said, “Man, are you kidding? You’re Stephen Stills. Anytime.”

This was 1973. In 1976, just three years later, he called me and said he wanted me to help him with a solo album that was called Illegal Stills. It’s really a cool record. After that record he called me and was like, “Let’s go down to Miami and start on a new record.” I said, “Great.” I’m on the plane and I think I’m going to play on a Stephen Stills record. When I show up in the studio, there’s Crosby and Nash. I’m like, “Holy crap. What’s going on here?” And then Neil Young shows up and it was a Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young record.

A very short-lived one.

Right. We started recording and it was going well. But what happened was Crosby and Nash just finished a duet album, Whistling Down the Wire. They had written all these songs and you give your best songs to an album. It’s not like they were out of songs, but they were kind of like, “Man, we’re spent on material. We just made a record.”

We started recording with the four, but then Crosby and Nash bailed because they were getting ready to go on the road to promote their duet album. So Neil Young goes, “Hell, let’s do the Stills-Young album.” They had never done that combination. It was really cool. All I could think was, “This will be cool since it’ll have some Buffalo Springfield flavor to it.”

We ended up doing the Stills-Young album, which had a hit on it, “Long May You Run.” But it was a bummer because I’m making a record with CSNY and then all of a sudden now it’s SY. Still, that’s not a bad thing. It ended up really good. We had a great time.

The tour must have been fun at first since you were re-working all those Buffalo Springfield and CSNY songs.

Oh, man. The live show was incredible.

I love watching Neil and Stephen play guitar together. They really bring out the best in each other.

It’s incredible. That happens a lot in rock & roll. You get two guitar players that play off of each other. Hell, like Joe Walsh and Don Felder. Those two guys, boy did they complement each other. They have two completely different styles, but they melded into one.

That band was fun and we sold out every show in a half hour. Unfortunately, Neil bailed after four weeks. [Laughs] He had obligations with Crazy Horse. They were going to make a record and tour and they were under contract. Hey, it’s only rock & roll, but we love it. [Laughs]

What’s your memory of learning that Neil bailed on the tour?

Oh, that’s documented. I still have my telegram. We had finished a show in South Carolina. We sold it out, a big arena. We got on the plane and flew to Atlanta, Georgia. We got to the hotel. Remember, this is 1976. They were using telegrams in 1976. When we got there, we got our room key, our room list and a telegram. We were like, “What?” I’d never received a telegram in my life.

It said, “Funny how things that start spontaneously end the same way. Oh well. Each a peach, love Neil.” It said “eat a peach” because we were in Atlanta, Georgia, the peach state. Everyone’s telegram read the same. I still have mine.

Was Stills livid? You had all those shows to play.

There was a whole summer of shows to play! Stephen was pissed. But that’s his brother. They love each other like brothers. But he was still pissed. “Why didn’t he tell us he had Crazy Horse stuff?!” We had to deal with the promoters and the lawsuits. I’m glad I was a sideman!

Didn’t you briefly try to do the shows without him?

Yes. We got Chris Hillman from the Byrds and we tried to salvage the shows, but when Neil Young bails, so does the audience. The same thing would have happened it Stephen Stills had bailed. Both those guys were big ticket sellers individually. But together they were huge ticket sellers.

We went back home and spent the summer doing nothing because everything was already booked. Everyone was already out for the summer. I couldn’t get booked. But when Crosby and Nash were done, they got together with Stephen in January of 1977. We were idle for about four months. Then we went back down to Florida to record the CSN album.

That tour you did with them was pretty amazing. They’d never gone out and done a proper tour as a trio. Everything before was in groups of two or with Neil.

That’s right. But the group was CSN. They always said CSN and sometimes Y. The 1977 tour was so incredible. I get goosebumps thinking about it. Those guys were so good. The vocals were outstanding. The music was outstanding. And remember, once in a while we’d do the song “Ohio.” Joe Walsh and I were at Kent State when all the tragedy went down. We were there. All of a sudden, I’m playing “Ohio” with these guys. It was bizarre. It was weird. It was exciting at the same time.

Moving into the Eighties, Joe Walsh has been very honest about all of his addiction issues in that decade. Were you worried about him?

All his close friends and family were worried about him. We did whatever we could do. That’s a really delicate situation in anyone’s life. Nobody was going to do an intervention. But when you look back, sometimes you think, “I love this guy so much, I don’t care if he hates me. I’m going to do an intervention.” But nobody did that.

Fortunately, he decided that on his own when the Eagles got back together. They knew, and he knew, that it wouldn’t work if his substance problem wasn’t fixed or remedied.

We were scared to death for him. I’ve known him since 1968. He’s a dear friend and I hated seeing someone going down the drain like that. You don’t condemn someone like that. You just hope and pray they’re going to find their way back to sanity. And he did. Man, did he. He’s so healthy now. He’s been clean and sober since 1994. That’s a long time.

At the exact same time, it must have been hard to watch David Crosby struggle.

Same thing. It was sad to watch. We tried to do the [Crosby, Stills, and Nash] Daylight Again album, which wound up being a multi-platinum record since it’s so good with “Southern Cross” on it. But that was a struggle, that album. It was so difficult because there’s a magical blend about Crosby, Stills, and Nash. You can take three other amazing singers and they don’t have that blend. There’s a magic to them. You can’t have that blend without C or S or N. And C was missing in action and having a lot of problems.

It’s funny when you look back at life and how things work out. Him getting arrested and thrown into prison changed his life. He and Joe Walsh, I believe, would have died soon after that. You can only do so much, and especially at their age. By God’s grace, Joe had to face the Eagles and rekindling that. And Crosby had to face prison and dealing with that.

You know what? They both came out on the other side sober and clean. What’s so great about those two particular guys, and I’m sure a lot of others, is that they maintain their sobriety. They’ve been sober and clean since they got sober and clean.

I was amazed to read in your book that you were present at the private Buffalo Springfield reunion at Stephen’s house in 1986. What an amazing thing to witness.

They hadn’t played together in about 20 years. Some of them hadn’t even seen each other in 20 years. They got together in that room and when they kicked it off, it was like 1968. They sounded just like the Buffalo Springfield of 1968. It was so good. Sadly, we lost Bruce [Palmer] and Dewey [Martin] before they reunited for real [in 2010].

How were all the CSN tours of the Nineties? I imagine it was hard having three bosses like that. There must have been times when they wanted different things out of you.

You have no idea! [Laughs] You have no idea how hard that is. Let me give you an example. We’re playing “Love the One You’re With.” The hi-hat pattern is 16th notes. That’s the way Stephen wanted me to play it. Well, Crosby turns around and gives me a dirty look. At the end, I say “What’s wrong?” He goes, “I don’t like that drum beat. Play eighth notes. Slow it down. I said, “Stephen told me …” He goes, “I don’t care. Play eighth notes.” I say, “OK.” I played eighth notes.

The next night, I do that and Stephen turns around and goes, “What the hell are you doing over there? I told you to play 16th notes.” There we were, just going back and forth. Graham Nash is just laughing. I say, “What am I supposed to do, Graham?” He goes, “I’ll talk to them.” It was hilarious.

They made a pact at that time, which was really good. Remember, those three guys are celebrities within themselves. They can all do solo tours if they want, and they have.

So they changed the rules. What they said was, “Whoever wrote the song is the leader of the band.” I go, “Great.” If we do “Long Time Gone,” I go, “Crosby, what do you want me to play on this?” If we do “Teach Your Children,” I’d go, “Graham, you want me to play it like the record?” And nobody argued. That was a good thing.

How was the experience of recording the CSNY reunion album Looking Forward? I’m sure once Neil enters the picture, it’s suddenly a very different dynamic.

It was awesome. A lot of people maybe don’t know the name, but Bill Halverson was the producer-engineer on the first Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young album. For Looking Forward, we did it in 1999 and 2000. For that album, the four guys brought back Bill Halverson. He made the first two records 30 years earlier. We set up the way Bill wanted us to set up. We did overdubs. We did vocals. We did everything like they did in 1969 and 1970.

It was fantastic for me to watch how they did it. It was so smooth that it made so much sense the way they recorded. All four of them stood around a microphone. They didn’t each individually record their tracks and then the engineer mixes the voices. They found a blend by physically moving closer to the mic or further away from the mic. All four guys around one microphone, there’s a certain blend to that that you cannot get when you have individual tracks.

You play drums on nearly every song on Looking Forward. Why weren’t you on the tour?

I think it’s because that’s the first tour that Neil Young did with the guys in 30 years. Neil had just done all these recordings with Jim Keltner, who is a fabulous drummer. Jim is amazing. Neil was a little nervous because he wanted to have one of his guys in there. Same with [Donald] “Duck” Dunn on bass. Well, Duck Dunn and Jim Keltner had been making records together and working with Neil Young for several years.

It was only every once in a while that Neil Young joined CSN. They hadn’t toured since 1974. I think that Neil felt more comfortable with a couple of his guys in there. I understand that. They did the tour, and then it was back to me with CSN. We resumed where we left off. It was a little disappointing. I really wanted to do it, but I understood. It was like, “Alright, fine. Whatever.”

How did you first hear about the Buffalo Springfield reunion of 2010 for the Bridge School?

I used to ride on Stephen’s tour bus and he was on the phone with Neil one night. I couldn’t hear the conversation. But he got off the phone and said, “Hey, we might think of doing an acoustic version of Buffalo Springfield for Neil Young’s Bridge School concert.”

I went, “Wow, that’s so cool.” But he said acoustic. That doesn’t include a drummer or a bass player. I went, “That’s so great, Stills. That’ll be so fantastic.”

That’s all we talked about it and six months went by. Weeks before the show, Stills calls me and he goes, “Hey, listen. We might have a bass player and a drummer. You’d play brushes and the bass player will play acoustic bass.” Remember, Neil insisted that the Bridge concert be all acoustic. That’s the way he’s done it all these years.

I said, “Just tell me the songs I have to learn and I’m on it.” It was so excited. We had a little two-day rehearsal. We only played about 40 minutes. I was blown away how fun that was. To hear those guys do those songs after all those years, and I’m in the band! It was so fun. Keep in mind, it was acoustic, so everything was kind of soft.

How was the show?

I was nervous. We were on last. The crowd went nuts when we went on. Elton John and all these other big-timers were at the show and they were all standing on the side of the stage. The audience couldn’t see it, but both sides of the stage were jam-packed with all these big stars. They wanted to see the Buffalo Springfield also.

It went really well. It went so well that we all got calls from Neil. He went, “Hey, listen. I had a good time.” I said, “Tell me about it, Neil. It was a fabulous time, man. You guys were so good. Seeing the three of you guys on the same stage was incredible. A monumental night.” He said, “Listen, let’s do this.” I went. “Are you kidding?” He went, “Let’s do this for real. I mean electric guitars, rock & roll, big time.”

We were supposed to go out in January [2011] and then it became February and then it became March. All of a sudden, we got the final word that we were going to go out in June. We did seven shows. We did two in Oakland, two in Santa Barbara, two in L.A., and then we did Bonnaroo. We were headlining Bonnaroo in front of about 200,000 people.

That was June. Then Neil had some stuff he had to do on his own. But they had booked 30 shows for the fall. We’re excited. I hate taking a summer off since I have to work, but I was looking forward to it because those seven shows were unbelievable. Looking forward to 30 dates in the fall, I could wait until then.

I don’t know what happened to this day, but it fell apart. Neil bailed again. He went off to do other stuff. He’s a free spirit. [Laughs]

I was at the Bridge School. When you walked onstage and went into “On the Way Home” and we heard the sound of Richie, Neil, and Stephen locking voices after all these years, it was truly one of the best concert moments of my life.

Yeah. I’m back there playing like, “I can’t believe what I’m hearing.” Back in 1968, everyone was listening to the Buffalo Springfield. They were huge. I even played in a local band that played a bunch of Buffalo Springfield songs. I was playing the songs with the real guys. It was quite amazing. Looking forward to that tour was … I can’t tell you how amazing it was. And I can’t tell you how horrible it was when it fell apart. [Laughs]

CSN toured until 2015. You weren’t there for the last few years of it. What happened?

I jumped ship because there was a couple of cancellations and I started getting some other work. I was kind of losing work because they were starting to cancel things here and there. But I did some Stephen Stills solo tours during that time. I was writing a bunch for a new record. They were kind of doing their own thing. It was kind of fading away. I don’t know what happened, but it wasn’t like every year we were on the road. I needed to work and so I started doing some other stuff.

Were you surprised when they broke up?

I am. It’s sad they broke up after all those years. I guess the problem with a lot of bands, and a lot of relationships, whether it’s music or not, is that things aren’t talked out when they come up. They eat at you and they burn at you. It’s like acid that eats away at your heart and soul. After so many years, all of a sudden it gets to a point … If something flares up, some situation, work it out, man. Talk it out. Don’t let that thing fester inside you because in 20 years or so it’s going to come out like an ugly beast.

It’s not that it was so bad with them, but there were a lot of issues that had never been brought up or talked about or resolved. All of a sudden, it got ugly and that was that. It’s sad. It’s not good.

Tell me about the Tom Petty/Joe Walsh tour of 2017. Obviously, nobody knew it would be Tom’s final run.

Oh, my God. That was heartbreaking. We had just finished a tour and one week later, Tom died. It was like, “Oh, my God. What’s going on?” He was just so wonderful to tour with. That was his 40th-anniversary tour. We had so much fun with those guys. They are such a great rock & roll band. They tell little jokes. They are little pranksters. They are a lot of fun.

Did you get any sense that he was going through health problems on that tour?

He seemed perfect. The only issue was that … in these arenas, the dressing rooms are quite a good distance to the stage, maybe 150 yards. He would get picked up in a golf cart and walk to the stage. The he’d walk up the steps to the stage.

That wasn’t a health thing. What happened is he had problems with one of his hips. Why put the guy through 150 yards of walking? Once he got onstage, he was fine. He was running around like he always did and it was a great rock & roll show. He only took that drive to the stage because of his hip problems. It had nothing to do with what was going on inside of him. It was a hip problem.

Nobody would have ever thought he had health problems on that tour. It was very sad. I was driving in my car when it came on the news. I had to pull over. I had to call somebody to find out, “Is this on the level?” I couldn’t believe it.

Tell me what it was like to shoot the Jonathan Demme movie Ricky and the Flash. In a million years, I bet you never thought you’d find yourself in a movie playing a Bruce Springsteen song with Meryl Streep singing it.

[Laughs] I know. Such bizarre things in rock & roll. What happened is I got this call one night and the voice said, “Is this Joe the drummer?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “This is Jonathan Demme.” I said, “Get the hell out of here. Jonathan Demme doesn’t call me.” He goes, “No, no, no. This is Jonathan Demme. I got your number from Rick Rosas, the bass player.”

I said, “OK, now it’s making a little more sense. Jonathan Demme, my goodness. What do you want with me?” He says, “We’re going to make a movie with Meryl Streep and she’s a rock & roller and she has a band that plays in the movie. I want you to be the drummer.” I went, “Wow, wow. Wait a minute? Really? OK. I’m in. You kidding?”

Filming that movie was one of the greatest experiences of my life because you’re talking about Meryl Streep. This is the big time in movie making. This is how the big guys and girls do this. It was amazing to watch what goes down and what it takes to make a film. Those guys and girls are working 12-hour shifts. It’s just amazing.

Jonathan Demme said, “We’re a bar band. We’re playing in a bar. We want to sound like a bar. We don’t want it to be all polished. If there’s any mistakes, as long as they aren’t complete screw-ups, just let it roll.”

It was all live. I had the time of my life. It was such an experience. I don’t have any visions of being an actor. That’s not what I do. But for a moment, doing that was so fun.

Are you hopeful that CSN might reunite in the future?

I hope so. There’s no reason not to mend fences. That’s crazy at our age and with their history. They are three individuals and they’re all different, but through music they found a common thread. There’s no reason to break that thread. They can iron out anything.

They accomplished something that dwarfs anything else they might do. For them to be able to mend fences, I hope they do. Whether or not I’m involved with it doesn’t matter. I hope they get back together because they aren’t getting any younger. There’s no reason at our age to hold any grudges. They’ve been through lot. They’re ironed out stuff before. I hope they do.

How is your lockdown going down in Canton? Getting bored?

A little bit, but I’m doing a lot of online sessions. I’m doing a lot of records right now. It’s not the same, but I’m working. I’d be going crazy if I weren’t working.

Are you hoping to be back on the road next year?

Absolutely. The worst thing about what happened here was that going way back to Kent State University, this year on May 4th was 50 years since the tragedy. They were going to have a big 50-year memorial event. Crosby was going to play and Joe Walsh and Barnstorm were headlining. They were going to bring in Chrissie Hynde in since she’s from Ohio also. We were going to do this big weekend memorial celebration. Then COVID arrived.

And since the Eagles were done for a while, we were looking at maybe doing some shows in the summer. We look forward to 2021 now. I’m an optimist, but I doubt anything will be going out before 2021.

Are you in touch with Joe? Is he doing OK?

I talk to him all the time. He’s fantastic. Bored to death. He wants to play. He wants to record. We’re talking about maybe in January getting together and starting to record a bit. We’re all trying to stay healthy and safe. I don’t want to look back on 2020. [Laughs] I want to forget about it some day.

Are you able to envision a day when you retire?

Only when I can’t do what I do now and when I don’t play well or feel good about myself playing out there. If I start to slip, I’ll accept that. At this point, I don’t see retirement. Ringo is 80 and he’s playing gigs. I love the man. So, no, I don’t see that. It’s a lifelong love affair, this music business.

I’ll tell you what I’m looking forward to: The first rock & roll shows of 2021. They are going to be crazy. People are going to be so out of their minds to get out since they’ve been deprived of rock & roll. It’s going to be fantastic. I’m looking forward to it.