MUSICIANS ON MUSICIANS Kevin Parker & Billy Corgan

MUSICIANS ON MUSICIANS

Kevin Parker & Billy Corgan

Two uncompromising studio visionaries on band politics, what the Nineties were really like, and how to keep rock exciting

Kevin Parker remembers hearing his older brother play Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream when they were growing up in Perth, Australia. “It was like an indescribable cross between optimistic and sad music,” says Parker. “All my friends were into Rage Against the Machine. Siamese Dream was my internal headspace album, I guess.”

That 1993 album helped inspire Parker to start making songs as Tame Impala, a solo project that has since grown into one of the biggest rock acts in the world, blending hazy guitars, disco beats, and huge pop melodies. That success has helped Parker, 34, become an in-demand collaborator for everyone from Rihanna to Kendrick Lamar, but he’s never met Corgan — who, it turns out, is a fan of his as well. “There’s a beautiful tastefulness in the tones that you choose, the way you move melody around in a nonlinear way,” Corgan tells Parker. “That’s all discernment. That’s the sign of a good musician.”

Corgan says he has an idea why Siamese Dream — Smashing Pumpkins’ career-making second LP, with Nineties alt-rock anthems like “Today” and “Cherub Rock” — was the one that resonated with Parker. “Every generation has their own gateway album,” he says. “For Gerard and Mikey Way, their [favorite Pumpkins] album was Machina, because it was very distressed and of that time, the dawn of the internet age. I see Siamese Dream as kind of an idealized statement. After that, we explored every variation: brute-force reality, true darkness. But people are really attracted to idealism. What’s weird is we almost killed ourselves to do it.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[2,2],[3,3],[300,461],[320,480],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Today, Corgan, 53, is on a new path of his own, having just finished CYR, a double album featuring founding Pumpkins James Iha and Jimmy Chamberlin; it’s also tied in with a five-part animated series. Says Corgan, “You have to just keep moving forward.”

Parker: I see the [mid-Nineties] as the golden era of rock & roll: When I started making music, all I wanted to do was be in that kind of romantic, grungy scene. It’s this fantasy that I hold in my mind now.

Corgan: I don’t think we realized what a great time it was: the breakthrough of alternative music. The Cure, Depeche Mode, U2 — there had been so many great bands [before]. But once Nevermind cracked everything open, suddenly the world was open to weird bands. We had our sanity, we hadn’t done too many drugs yet. The golden era, to use your words, was ’91 to about ’96. Then it was over.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[2,4],[4,2],[320,480],[3,3]])

;

});

Parker: I think that’s OK. It’s OK that things don’t last. You know what I mean?

Corgan: That’s life, you know?

Parker: Sometimes fans will say, “Oh, man, I wish you had that sound again.” I feel they’re more in love with the time when they fell in love with that album.

Corgan: It’s more tied to their emotional connection to a particular moment in life. I made an album called Oceania in 2012. I sort of said, “I’m going to allow myself to play in that kind of language again,” because I had sort of shut the door on it. So I just kind of wrote those riffs and let it happen. I did find something that moved me, and I was able to revisit certain themes. What’s weird is, now we’re eight years later and people talk to me about the record all the time.

I’m at this midpoint where it’s time to look through the scrapbook, but also look forward. You have to take stock of where you’ve been. It sounds a bit boorish, but when you’ve experienced fame at an international level, it’s a dopamine rush that’s reserved for very few people on this planet. People talk to me about certain years of my life, and it literally is a blur because in that one year we played 200 shows. At some point you have to survey the damage and step back and say, “OK, what did this do to me?” It’s not like I get to go back to the guy I was before. It doesn’t work like that. It is ultimately transformative.

Parker: Isn’t it funny how it’s difficult to appreciate things that we look back so fondly on? Not to be topical of the moment, but it’s funny how much I’m craving rocking up to an airport hungover and having to check in right now, because I haven’t been able to do it. We released an album in February and the tour [had] just kicked off. Smelling the air conditioner of a tour bus, that kind of recycled air when you wake up in the morning — it’s funny how those are the things that we don’t really appreciate in the moment.

Corgan: That’s what I love about your music. It really celebrates the moment. I was listening to some last night and I just think you so beautifully captured the moment that we’re in. I was raised, like many people, on the Beatles and Led Zeppelin. Our way of rebelling against that was to play it louder, faster, with weirder lyrics. So as the world has sped up, as communication became global, I started hearing a lot of music that I didn’t understand. In essence, it’s not based in the same rules that I would liken to classic songwriting. It’s taken me a while to understand that to make music of today, you have to be sort of unattached and more free than we were. Your music bridges the gap. I hear hooks that remind me of the Bee Gees.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Parker: Absolutely!

Corgan: I also recognize that young people are growing up in a far different world than we grew up in. They’re less tied to the rules, and it’s a beautiful thing.

To be somewhat critical of the age that I came from, there’s a lot of complaints here in America about how the boomers have ruined the world. They’ve kind of bankrupted the country, they’re living a lot longer than their parents did. I don’t have any bone to pick with the boomers, but we grew up in a very, very big shadow of the boomer bands. These artists have held on a lot longer than anybody would have imagined. For us coming up, it was like, “How the hell do you compete with that?” So what I like, whether it’s conscious or unconscious, about the new generation of great artists is they seem to me to be the first generation that’s no longer living in that shadow.

Parker: It’s funny, I feel like the best thing about music now is that there are kind of no rules. I feel like it’s one of the only good things about music now. We don’t have much else to rely on, other than that it can be done any way. [Things] are much less linear, in the way that there used to be mainstream music and alternative music. Those two things don’t exist so separately anymore. Even with pop music and rock & roll and hip-hop.

Corgan: We grew up in a world where you were given a lane and you were expected to stay in that lane. If you veered from that lane, you would get a bunch of weird shit about it. We were like, “Well, the Beatles did ‘Revolution’ and ‘Strawberry Fields’ and ‘She Loves You.’ ” People would go out of their way to enforce the rules. Whatever that was is over.

Parker: It’s also less comforting these days that the type of music you listen to it defines your identity less. I feel like when I was starting into rock & roll, if you listened to a type of music, it defined who you were, almost as though it defined which table you sat at at lunch. These days it’s so much more scattered.

Corgan: But the beautiful thing is, whether you know it or not, you’ve figured it out. That, to me, is a talent. It’s a rare talent, because I know how hard that is. Everyone thinks you can just throw a bunch of stuff in a blender and mix it up and somebody is going to want to drink it. It doesn’t work like that.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Part of being a good songwriter is discernment. It’s having the ability to discern what belongs and what doesn’t. I think you have great discernment. There’s a beautiful taste in your music. When I listen to a song, I don’t want anything to take me out of the vibe. So if an artist produces a new element, that’s got to take me on a new journey, not take me off the path that I’m on. The way you move melody around in a kind of nonlinear way — that’s all discernment.

Parker: I guess I like to not feel predictable. I like feeling like I’m just beyond knowing what I’m doing, you know? It’s a difficult feeling to describe. You know when you’re making a piece of music and you feel like you’re kind of just outside your boundaries? One of the things that I love about collaborating is feeling like I’m out of my depth; if it’s hip-hop or electronic music, going in there and going, “Geez, what do I have to offer here? I’m way out of my depth.” Because, selfishly, my favorite thing about collaborating is learning something new.

When we got a record deal, the music that we got signed with was all my home recordings. Then, all the albums from there were all me, but it was this awkward power struggle. Because I didn’t want to be the boss [in my band], but I wanted it to sound like I wanted it to sound. I think Billy Corgan and the Smashing Pumpkins were sort of a template that we would consider a lot. The other was Brian Wilson. How did you navigate that role? I know that you’ve had such strong visions with your music, but still had to deal with people and band members who are your friends and people you love.

Corgan: I’ll try to be succinct. Like a young lover, I had a romantic idea of what a band was. My father had been in a band. I always heard him complaining about the other musicians. I didn’t want to be that type of band. I wanted to be in the Beatles. Socially, we were like a gang. We moved in one direction. Of course, there were early indications that it was my thing, as far as the songs, but it didn’t really come to a head until we first started recording, and then producers like Butch Vig would say, “It needs to be up to this standard” or “It needs to be like this.” Suddenly, I was kind of put on the spot, because I’d made the majority of the demos, like you. People would go, “I want the thing I heard on the demo.” I’d go, “Well, that’s me.” “Why can’t you do it?” “Band politics. I don’t want to hurt somebody’s feelings.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

So over time, we kind of reached an agreement internally; we were kind of cool with that, or at least I thought we were cool with that. Not too ironically, we were doing an interview for IndieLand around 1993. We were sitting in a cafe, and the guy interviewed me first and then James [Iha] and D’arcy [Wretzky], who were an on-again, off-again couple. I ate my soup, but I could hear what they were saying. One of the band members said, “Oh, he does everything.” It was weird — like, “OK, I thought we had an agreement to keep that to ourselves,” because it was going to be a problem. Even if you look at the way other bands of my generation were presented initially, you later found out they were really kind of solo projects. [People] would use words like “tyrant” and “Svengali.”

Look, I grew up poor-ish. I watched my father struggle and play five sets a night and complain and get lost in drugs. I was like, “That’s not going to be me.” So I had this ambition to get not only out of my social situation, I had this ambition to live my dream. And it was working. We had hits and massive sales and were playing festivals, but behind the scenes everybody is complaining all the time. I’m saying “Well, what do you want me to do?” Again, this is pre-Pro Tools; it wasn’t like you could just go fix something. It was a different level of expectation.

Parker: Totally.

Corgan: I think eventually we found this kind of peace with one another, where on one level I figured out what I was good at and I stopped apologizing for it. It’s really [not] personal. I think on the other side, they’ve accepted that over the course of so many years, I’ve sort of proven my focus and my dedication to the craft. So there’s beautiful respect there now where we all realize what we’re good at.

“You said Siamese Dream almost killed you,” says Parker. “I’m intrigued how it almost killed you.”

Parker: Isn’t it funny that it takes that equilibrium to be reached for there to be harmony? All I wanted was to be in that gang. There was also something else tugging at me, which is to make music that I had a vision for.

There was so much confusion in the early days. We had the same kind of thing, where it was between the three of us, but we all knew it was me making the music. But they also had to do interviews. The interviewers would ask the guys what the influences were. Sometimes they’d sort of bullshit and string the conversation along, and sometimes they’d go, “We don’t fucking know, it’s just Kevin.” That confusion came to a head, and then it all blew open. It was like, “OK, something is wrong here, with the kind of marketing of it all. So we’re just going to call it what it is, which is basically a solo project.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Then, from that, I basically had to just take the role of leader and boss. Up until that point, I’d hated that idea. I never wanted to be a boss, but I had a vision of music, you know? So I kind of just had to accept that role, which took a lot of growing up, I guess, and maturing. It works so much better now. We’ve never been happier than the past few years.

One of the things about the heaviness of Smashing Pumpkins that is kind of unique is that even though it’s absolutely raging — I read somewhere that at some point there were, like, 60 guitars; I don’t know if that’s true; feel free to confirm or debunk — it still always feels like I’m just lying in a cloud, you know what I mean? Even when it’s just, like, “Cherub Rock,” any of those songs from the album, even though it’s just like raging fuzz, it always just seems like the fuzz guitars are layered and played so well. I guess it’s kind of like lots of octave and power chords so they kind of jell together well. It always just feels like I’m just bathing in a giant white cloud of fuzz.

Corgan: We’ll put that quote on the album. I’m still chasing it. On our new record, the songs that have just come out, I’m still chasing that feeling. Maybe that’s part of it, I can never quite get there. It takes a lot of time, a lot of studio guile to figure out how to put those pieces together. There’s tracks with tons of guitars. I just go and go and go until it got close to what I heard in my head.

Parker: I guess that’s just one of the sort of amazing contradictions of the sound of Smashing Pumpkins. You said Siamese Dream almost killed you. I’m intrigued how it almost killed you.

Corgan: Well, that’s a great question. We were under tremendous pressure to succeed. It was well-known that if you didn’t produce a bunch of big radio songs or MTV songs, you were dead, and they would just drop you. I’m sure it’s not any different. It was the ’92 version of that.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Our producer was coming off Nevermind, so he was under pressure to prove he wasn’t a one-hit wonder because he was an indie guy. Then I think the inner politics: All three members reacted negatively to what they were being asked to do, because we had to make this once-in-a-lifetime album. We were working 12 to 13 hours a day; the long hours, the isolation.

I think it exposed what was fragile in our relationships. It built up to people quitting, people going on drug binges. It was everything under the sun. Then people would walk through the door and we’d play them the basic tracks and their jaws would just be on the floor, like, “What the fuck?” So we knew we were doing something right. Then you’d close the door and go back to “I hate you.”

That tension, the toxicity, if I could put it one sentence: It was the toxicity of chasing your greatest dream, while at the same time the people in the room with you don’t like you very much. It’s hard enough to chase your greatest dream when people are patting you on the back saying, “You can do it.” When they almost want you to fail because it will prove them right even if it hurts them, which is kind of a weird thing …

Parker: It’s so human, though, isn’t it?

Corgan: What’s funny is the wounds are healed and we’re so long past it, it’s like talking about something that never happened. In a weird kind of way we needed to go through that to figure out how we really loved each other, that our ties were deeper than an album or a song or a moment. At the time, I thought I was going insane. I hate to make it a romantic thing, but it’s like finding the greatest love of your life and it doesn’t work. Like what do you do? Do you walk away from the greatest love of your life because it “doesn’t work?” Or do you just keep fighting? We fought and fought and fought. Eventually it destroyed the band.

But just one addendum, because it’s oftentimes a misconception. We didn’t fight about the music, which is really the weirdest thing about it all. We were always in alignment with the music. It was more about how we made the music that was the problem.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Parker: That’s really profound. That’s a really interesting point. It’s so funny that you can all want the same things and be on the same page, but because of other things at play, it can cause such disruption. It can make you want to destroy something you love.

Corgan: In our case, we did. We did destroy it. We had to learn the hard way what we had destroyed. That’s been part of years of actually rebuilding our relationships and our affection for one another so we can put that engine back together.

Parker: That’s got to be just such a common process, emotionally and socially. It happened with us. There were times that I was like, “Fuck this, Tame Impala is not a touring band,” you know? It was so counterproductive to have that idea. There were so many times I would just sort of sabotage. Because you’re with people you love and the people you are fighting with are the most important people in your life, you’re willing to sacrifice anything to prove a point to them. You know what I mean? Even if it means ruining a gig, ruining a concert, because getting a message to them is more important to you than anything. You know what I mean? Can I propose a topic?

Corgan: Sure.

“Everybody thinks they know how to put on a guitar and say something that 10,000 people aren’t going to like,” says Corgan. “Try it. Until you’ve had people throwing jars of piss at your head, you’re not on the edge of anything.”

Parker: I want to ask how you feel about the current state of rock & roll. Sometimes I wonder, has the driving force of rock & roll been replaced by other types of music?

Corgan: In terms of approach and style, I think that the closest thing to rock & roll is hip-hop. There unfortunately hasn’t been the evolution there in terms of how to play, to make the guitar as valuable as a synthesizer or something. If you’re a guitar player and you have a vision like I did or you do, then you’ll figure it out, even if it means turning your guitar upside down and running it through a blender. That’s just the way it’s worked, since before Elvis and through Elvis. I think those pioneers and heroes, I don’t think they would have stuck on it. They would have been on to whatever was the most exciting thing.

Rock & roll has to be willing and able to be dangerous. When I hear great artists like yourself or Grimes, you guys are figuring out a way to bring what I would call the violence and the beautiful sort of fuzz into the current state. The moment rock gives up the mantle of being willing to step over a particular line, it’s dead. Some of the most powerful moments in the 20th century [happened] when a musician was willing to say, “I’m going to go against the grain of what is the thinking of the times,” whether it was Elvis’ integration of different worlds as far as music went, Bob Dylan standing on the steps near Martin Luther King playing “Blowing in the Wind,” or the Beatles singing “Revolution.” There are moments in time when musicians are willing to go against what everybody thinks at the time and say, “No, this is bullshit.”

I don’t mean it as condemnation because it’s not my flag to march with at this point in my life, but I do think artists have to be willing to step over those lines. Everybody thinks they know how to put on a guitar, stand up, and say something that 10,000 people aren’t going to like. Try it sometime. Until you’ve had people throwing whiskey bottles and keys and jars of piss at your head because they don’t like what you’re saying, you’re not on the edge of anything.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid8’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Parker: Has that happened to you?

Corgan: Oh, yeah. We’re talking near-riots, man. You have to remember that when alternative music kind of blew up around ’93, ’94, a lot of the bands were big, but they weren’t big enough to play arenas. So you’d be stuck in these armories. You’d be playing in Indianapolis in an armory, just a big square box. You’ve got 4,000 people in there moshing. Then you say the thing that the audience doesn’t want to hear. Now they’re trying to climb over the barricade to try to kill you. I’m standing onstage saying “If anybody gets on this stage, I’m going to hit you in the head with my fucking guitar.”

Parker: Are you nostalgic for those moments?

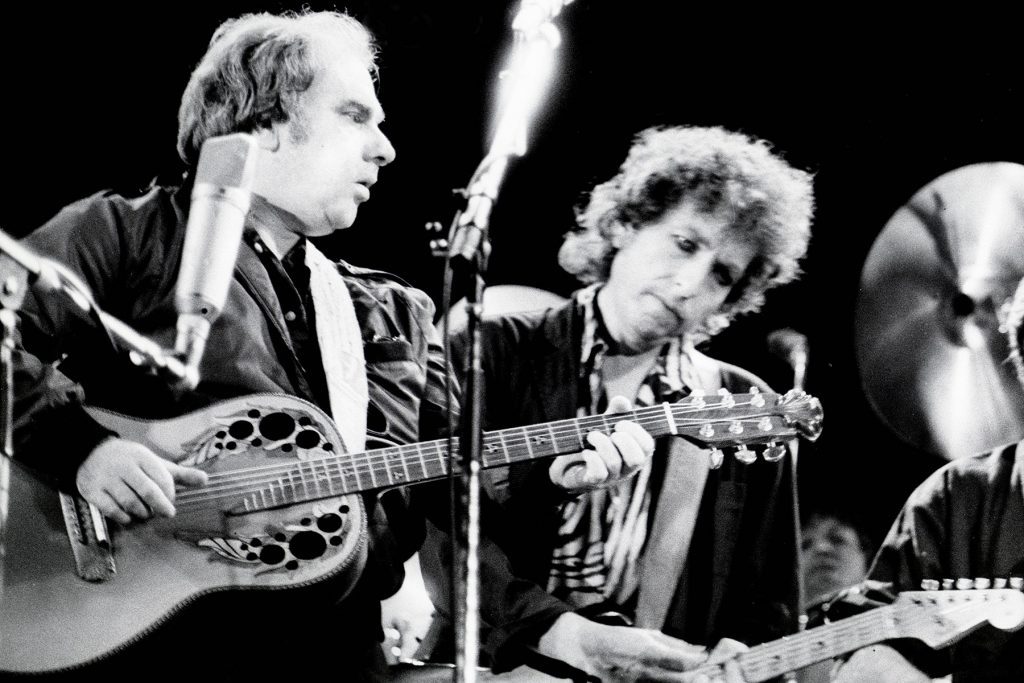

Corgan: Not at all. It’s more like a chuckle. Like, “God, I can’t believe that happened.” I’ll see the photo of me and David Bowie and Robert Smith and Lou Reed from David Bowie’s 50th-birthday concert, and I’ll think, “Oh, that’s so cool, that’s so beautiful.” I’m telling you, there’s never a more beautiful moment than being in this moment, with [my] children, happy. I can call up my band members on the phone and everybody gets along. That’s just as beautiful, if not more beautiful, in my mind.

Billy Corgon, David Bowie, Lou Reed and Robert Smith on January 9th 1997 at David Bowie’s 50th Birthday Celebration Concert

Kevin Mazur/WireImage

Parker: I made some notes before we chatted. The only other thing I had was that whenever I listen to Siamese Dream, it’s like a big hug. That’s all I’ve got.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-mob-article-inbodyX-uid9’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Corgan: There’s your headline.

Parker: Man, it’s been a massive honor to speak to you. It’s funny because I’ve met a lot of my idols over the years. The list of my idols that I haven’t met is dwindling. I’ve always wondered if I’ll ever bump into you somewhere, or get the opportunity to speak to you. Tell me this: Did you guys have plans to come to Australia before this whole coronavirus shutdown?

Corgan: You know, it’s a sad thing. No promoter will bring us over.

Parker: What are you talking about? I’ll have a chat with my people.

Corgan: We’ll get you up for a Siamese Dream song.

Parker: Oh, my God, that would be amazing. That would be a dream.

Corgan: You got to put yourself in the big fuzzy cloud!