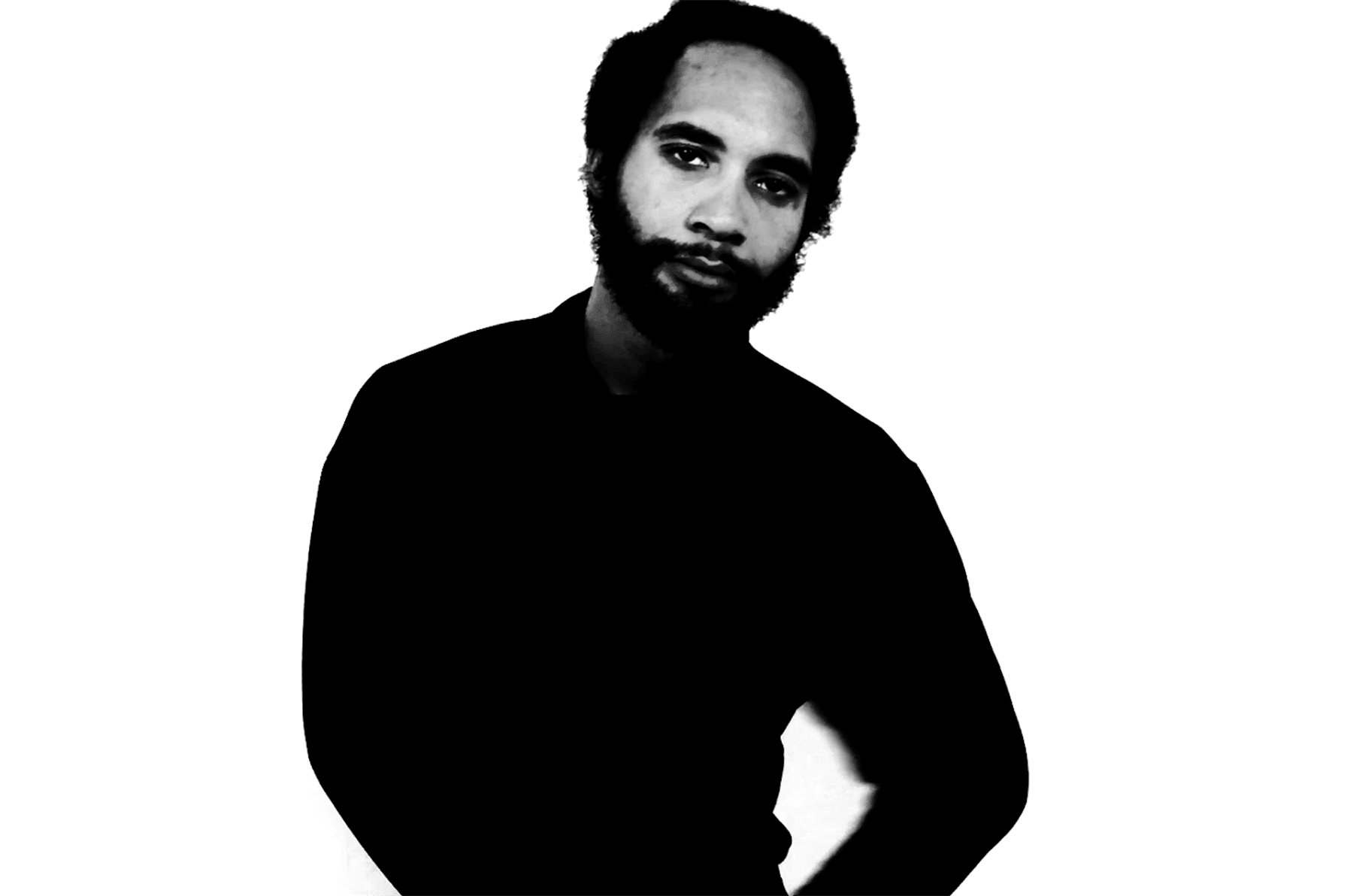

Robin Pecknold’s Season of Rebirth

In the spring of 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic tore through New York City at terrifying speed, Robin Pecknold stayed home in his rented one-bedroom apartment in Greenwich Village. “I wasn’t being creative at all,” says the Fleet Foxes singer-songwriter, 34. “There were some dark weeks where I would end up waking up at 7 or 8 p.m. and stay up until noon. The world just seemed like it was more sane at night.”

On top of everything else — “the stress that we’ve all been going through, just by being alive in 2020,” as he puts it — he had an album to worry about. He’d spent the previous fall and winter recording instrumental tracks for a new Fleet Foxes project, but the songs were half-finished at best, with no lyrics or vocals in place and no clear ideas for what to do next. “It was this extra albatross,” he says. “It was unclear if I would just abandon it, or if it was going to come out in 2022, or what.”

That feeling lasted through March, April, and May. Then, in June, Pecknold had a breakthrough. Heading north for long, aimless loops around the Catskills region in his Toyota 4Runner, with rough mixes playing on the stereo, he found himself pulling over to the side of the road to jot down new lyrics. Soon he had enough to fill an album. “I put 6,000 miles on my car in three weeks,” he says.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

The songs that came into focus on those drives became Shore, the fourth Fleet Foxes album, released today at 9:31 a.m. in sync with the autumnal equinox. It’s a gorgeous folk-rock song cycle about life, death, and art, full of deep mourning and glimmers of relief on the other side. Track for track, Shore is the most immediately rewarding Fleet Foxes record since their brilliant 2008 debut. With virtually no advance promotion, it arrives as a welcome surprise in a still-unsettled world. “Catching the end of the summer, it felt like the right time for the music to come out,” Pecknold says. “If there were ever a time to try it, it seemed like it was now.”

He began writing shortly after the tour for 2017’s Crack-Up, the album that ended a multi-year hiatus in which he quit music, enrolled in undergraduate classes at Columbia University, and learned to surf. (That last part is also why he drives an SUV: “I got it because the back window goes down, so it’s easy to put a surfboard in the back,” he says.) Hoping to avoid another long gap between albums, he got the instrumental tracks down at studios in upstate New York, Paris, and Los Angeles, working closely with engineer Beatriz Artola and select session collaborators.

The music was sunny and full of light, but finding a strong lyrical perspective to match proved harder. “I resent lyrics sometimes,” Pecknold says. “I’ll spend all this time on a melody or a chord progression, and then I can ruin the song with a bad lyric. It’s very delicate. You can’t have a classic song with bad lyrics.”

Even before the pandemic, he felt himself hitting a wall of creative exhaustion. “There was just no subject matter,” he says. “It was a mistake that I made in planning the album — living with the gibberish scratch vocals for a year and a half is a bad idea.”

As the lockdown period stretched on, he began to see a novel way out of that dilemma. “The whole experience gave me so much additional perspective on what community means, what death means, what gratitude means, what privilege is,” he says. “This is my least personal album. I wanted it to be mostly about how I felt about other people.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

There’s no better example of this approach than “Sunblind,” the stunning litany of thanks for musicians gone before their time that appears near the start of Shore. “For Richard Swift,” Pecknold sings, invoking the beloved artist and producer who worked with the Black Keys, the Shins, David Bazan and many others before his death in 2018. Like many musicians of his generation, Pecknold knew Swift and mourned his loss. But he explains that the line is really there to honor what Swift meant to indie rock more broadly: “So many of my friends were even closer to him. Seeing how his passing affected them … It was difficult for this community.”

“Sunblind” keeps going from there, reciting the names of Judee Sill, John Prine, Elliott Smith (a “hugely, hugely formative” artist for Pecknold, who remembers going to Smith fansite sweetadeline.net in the early 2000s to look up guitar tabs), Silver Jews’ David Berman, and more, mingling recent tragedies with older ones in a cosmic scroll of appreciation. Then the song bursts into sunshine, with a celebratory chorus that came to Pecknold just a few weeks ago: “I’m going out for a weekend/I’m gonna borrow a Martin or Gibson/With Either/Or and The Hex for my Bookends/Carrying every text that you’ve given/I’m gonna swim for a week in/Warm American Water with dear friends/Swimming high on a lea in an eden/Running all of the leads you’ve been leaving.”

“That chorus is saying I’m going to live as best I can, in thanks to these people, because they can’t, or they couldn’t,” Pecknold says. “It’s zeroing in this idea of gratitude just to be alive. I’m so lucky.”

That same emotion radiates throughout Shore, which Pecknold sees in part as a love letter to the music that has inspired him throughout his life. “Anything that sounds like a relationship song or a love song is really just me talking to music, [expressing] how grateful I was feeling to be working again,” he says. “This invisible thing can be so meaningful to you, and so much more real in some ways than actual, tangible things.”

Another key song on the album, “Jara,” is named for Victor Jara, the Chilean protest singer who was killed in the U.S.-backed right-wing coup that brought down socialist president Salvador Allende in 1973. With its mention of “the great white tyrant” and an oblique reference to Jara’s sacrifice (“Now you’re off to Victor on his ladder in the sky …,” Pecknold sings over bright, burbling chords), the track is the album’s most direct reflection of the injustice Pecknold saw around him as many of his downtown neighbors vacated their townhouses at the start of the pandemic. “Being in New York, seeing this neighborhood empty out, and knowing that not everyone had that opportunity … Everything about this is just so unjust,” he says.

Later in the summer, as Black Lives Matter protests filled New York’s streets, he joined at least one march that passed by his block, and used his car to bring ice and other supplies to occupiers who needed them. He wrote the lyrics to “Jara” thinking about others who took a more active role standing up against racism and oppression. “In the song, the speaker is equating a friend of theirs who’s a very engaged activist to their own personal Victor Jara,” he says. “I have a couple friends who are very politically engaged, and I find them inspiring, the same way you would find Victor inspiring.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

One of the lightest moments on the album comes with “Young Man’s Game,” which pairs an energetic, liberated groove with lyrics that gently mock the existential quandaries he was writing about just an album or two ago: “I could worry through each night/Find something unique to say/I could pass as erudite/But it’s a young man’s game.”

“I used to think [the idea of] a young man’s game was something to lament — like, ‘I’m going to age out of this glory,’” Pecknold says. “So it was funny to turn that around. Actually, it’s great to get older and not make the same mistakes and not have the same hang-ups.”

Aside from that and a few other moments, Shore is a remarkably outward-looking album. Its recording process was full of new collaborations, with a cast of three renowned drummers (Grizzly Bear’s Christopher Bear, the Dap-Kings’ Homer Steinweiss, and Angel Olsen collaborator Joshua Jaeger) giving Pecknold’s songs a new rhythmic edge. The very first song on the album, “Wading in Waist-High Water,” showcases the voice of Uwade Akhere, a mostly unknown young singer whom Pecknold found after someone sent him a clip of her singing Fleet Foxes’ “Mykonos.”

Grizzly Bear co-frontman Daniel Rossen shows up on another song, “Cradling Mother, Cradling Woman,” adding the kind of richly textured instrumental crescendo that Pecknold once both admired and shied away from in his own early music: “He’s such a unique player. I was always grateful to get lumped in with [Grizzly Bear], back when. But I was very conscious to try and not do anything that felt too much like them, because we share so much taste.”

The same song features a small sample of Brian Wilson counting in the band, taken (with permission) from the Pet Sounds Sessions box set that Pecknold encountered and loved when he was growing up in Seattle. The sample comes from an outtake of “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)” in which Wilson is heard giving instructions on how to layer vocal harmonies: “He’s making this insane world, this crazy egalitarian magic, with just his voice. … It was like watching Picasso paint,” Pecknold says. “Hearing that clip, when I was a teenager — that more than any other thing made me want to get into overdubbing and making songs.”

The other four members of Fleet Foxes — Skyler Skjelset, Morgan Henderson, Casey Wescott, and Christian Wargo — are notably absent from Shore. In fact, though they have contributed to varying degrees to Fleet Foxes’ previous albums, Pecknold says his bandmates have always been more like touring members. “The studio albums have always been predominantly my work and my vision,” he writes in an artist’s statement provided to the press for this album. “I’ve always handled all the songwriting, most of the vocals and harmonies, and most of the recording of the instrumentation.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

This balance of roles hasn’t always been entirely clear to the listening public, in part by choice. “On the first Fleet Foxes album, I just didn’t list who played what, because I didn’t want to have certain songs be all me,” he tells me.

Fleet Foxes’ second LP, 2011’s Helplessness Blues, was “more of a solo album than any of these records,” he continues. “For Crack-Up, me and Skye [Skjelset] were working on it together — he was engineering and helping me produce — and then we had a week of sessions with the other guys adding ideas. I thought that was how it was going to go this time, but with lockdown, the logistics … I don’t know. I just wanted to finish it and get it out.”

At one point, he expected to be playing these songs with the band on tour this fall. “Part of the whole idea of this record was songs that would be fun to play live,” he says. “It won’t happen for a year, and that’s weird.” But it’s also been freeing in a way: “We can’t go on tour. There isn’t this path to insane monetization. That’s just the way it is. The record’s just the record. That feels really great.”

Pecknold thought about self-releasing Shore through Bandcamp — “Let’s just throw it out there, who cares what comes of it?” — before partnering with Anti-. Since finishing the LP, he’s begun trading files with his bandmates, “bouncing ideas back and forth, co-writing in little groups.” “I’ve never written songs with the guys in the touring band, but they’re all great musicians with interesting perspectives,” he says. “It’ll be fun to work with them. Maybe we can get those [songs] together for next year, and when it’s time to go on tour there’s something to accompany it.”

The process of making Shore has left him feeling newly comfortable with his life and career, shrugging off some of the cares that once preoccupied him. “I used to think that all I needed to do was two albums, because that’s all anyone ultimately listens to or cares about,” he says. “Now I’d rather think about a filmmaker’s career, where they can have eight awesome movies.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

He doesn’t want to come across as blithely unconcerned, but he sounds happy. “I’m still anxious and worried, but it’s not about my own stuff,” Pecknold says. “It’s about what’s going on in the world. This is one weird little moment where there might be some optimism. We don’t know what’s going to happen in November; maybe it all falls apart. But there’s a little bit of hope in the air in this moment, and I can’t say if that is always going to be true.”