Gabriels Blew Away Elton John. Now They Want the Rest of the World

Gabriels have just five songs to their name, but one of them verges on the sublime. “Professional,” which came out toward the end of 2020, embraces the off-kilter swoon of jazz vocalists like Billie Holiday or Andy Bey, as singer Jacob Lusk sends his voice gently dive-bombing to the floor and then yanks it back up like a yo-yo, ducking and weaving around a glum string section. The strings fall away, leaving Lusk alone for a late-night, empty-bar, alone-at-the-piano interlude, and then the fireworks begin: A lazy beat enters, spurring the singer to unleash a series of wounded pleas. The high notes are gorgeously multi-tracked and easy to decipher — “You were s’posed to/You were s’posed to love me” — but there’s also a quavering harmony on the low-end, like the soft whimper of man who was just dunked in an ice-cold bath. This portion of the song is less than 60 seconds long, and it’s mesmerizing.

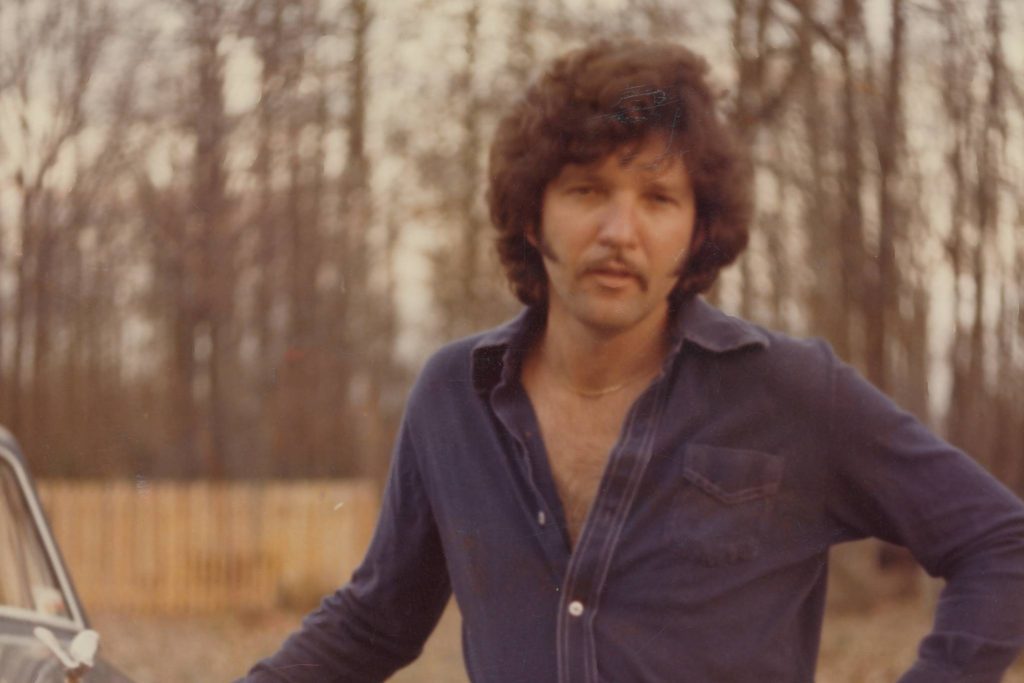

“I’ve done songwriting stuff in the past where it’s like, ‘this is a radio killer; this is for R&B or for Adult Contemporary; let’s make this R&B record that’s gonna compete with Tank,’” Lusk says, exaggerating his voice to lampoon hit-thirsty record executives. His work in Gabriels, a trio with producers Ari Balouzian and Ryan Hope, is “not doing that,” the singer continues. “This is a breath of fresh air for me.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

The group announced their signing to a major label on Thursday — Elektra in the U.S. and Parlophone in the U.K. This is not just surprising because the group scoffs at the idea of chasing commercial trends; it’s also notable because Gabriels have been on a slow-burn trajectory in a short-fuse era.

More than ever, the modern music industry is obsessed with what’s called “research.” Contemporary technology allows executives to track artists’ growth nearly minute-by-minute on streaming services and social media platforms. As soon as a song or artist, but usually a song, starts to gain momentum, every label acts like a hound finally off its leash, all bounding after the same quarry. Signing artists that already have a popular sound on TikTok is thought to minimize risk — a spark is already lit, so all the label has to do is add napalm — and labels are anxious to reduce risk as much as possible.

Gabriels have followed a more old-school path. At a time when artists shoot out songs like they’re about to be banned from studios for life, Gabriels have put out just five songs since 2018, a mix of haunting gospel, brittle electronics, and harmony-drenched doo-wop — the combination sometimes sounds like someone is playing Philadelphia soul records arranged by Thom Bell at the wrong speed. And instead of displaying viral growth on a platform like TikTok, Gabriels have built a profile by earning nods from old-school tastemakers like Gilles Peterson and the Los Angeles station KCRW. There’s a note of pride in Hope’s voice when he calls the group “the most social media unsavvy trio.”

But they’re also wary of being tagged as yet another retro group in a landscape crowded with revivalists. “It’s not cosplay bullshit,” Hope says. “That’s not what the fuck this is,” Lusk agrees.

Lusk has an impressive resume, working as a choir director and a background singer for Diana Ross, Gladys Knight, Nate Dogg, Ledisi, and Beck, among others. Balouzian came up composing music for movies, which is how he met Hope, a hyper-chatty and self-effacing music video director — “I blagged my way onto the shoot” for Massive Attack’s “False Flags,” he says cheerfully, “with absolutely no credentials” — and DJ-producer who also harbored an interest in film composing.

The three connected in 2016 while putting together music for a commercial; Hope and Balouzian were so impressed with Lusk’s talent that they went to his church in Compton and “basically ambushed him there so he had to talk to us.” Even while making music for a commercial, “Jacob was leading and arranging the choir in a way that made it interesting no matter what the material was,” Balouzian recalls. “We were recording harmonies and vocal arrangements, and all the other singers in the choir were looking to him for direction. He was coming up with stuff on the spot very quickly.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Lusk was also struck by how quickly the three men connected, even though the “crazy” pair had stalked him at church. “In the studio, it’s like you have a golden doodle, and English bulldog, and maybe a golden retriever, and they understand each other’s bark language, but no one else knows what the fuck they’re talking about,” Lusk says. “That same energy happened when they came to the church.”

While holding on to their various rent-paying gigs, the trio began to meet every few months to work on new music. They didn’t put anything out until 2018, when Hope was directing commercials for Prada, and the trio decided to compose a 60-second piece of music, a glacial dirge about a dangerous infatuation, to accompany the footage. They liked the track enough to blow it out to two and a half minutes, and R&S Records — known for releasing crucial electronic music from legends like Kevin Saunderson and Aphex Twin — picked up the song.

Gabriels’ slow, steady approach has also given them time to develop a backslapping rapport — they’re quick to poke fun at each other, and themselves — that’s even evident over Zoom. They bicker good-naturedly about Lusk’s tendency to be “a little grand,” Balouzian’s obsessive nature in the studio, and Hope’s casual dismissal of some of the producers, even famous ones, who hoped to remix Gabriels’ work. In conversation, Hope and Lusk barrel forward, pausing only to ask this reporter not to publish comments the second after they say them, even when it’s something seemingly banal. “They’re fucking funny,” says Duncan Ellis, who signed the group to his Atlas Artists label and management company.

Ellis stumbled upon the group when the Spotify algorithm served him up “Love and Hate in a Different Time,” which melds chamber pop, the reverence of Sunday’s sermon, a stiff Motown march, and a synthesizer like an erupting tea kettle. Ellis also manages Celeste, the U.K. singer who displays her own sterling pipes on modern soul songs like “Father’s Son;” he initially started messaging Gabriels on Instagram “like a fanboy” in the hopes of getting them to work with his other client.

But when Ellis finally made contact with Gabriels’ then manager, he was rebuffed. The band later reached back out to the veteran executive on their own and ended up signing with Atlas — which in turn licensed the music to Elektra and Parlophone — earlier this year, marking the first ever deal Ellis inked without meeting a group in person.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

He’s aware Gabriels’ path to this point is unusual in the context of the contemporary major-labels ecosystem. (He says that, among others, the indie Partisan Records also pursued the trio.) Gabriels’ story is “very much anti the model right now,” Ellis says. But while he understands the rationale behind chasing viral songs on TikTok, he jokes that it’s “Tiktoxic.”

His focus is elsewhere: In England, “Love and Hate in a Different Time” has a toehold at radio that Ellis hopes to expand. And Gabriels are preparing for their U.S. television debut on Jimmy Kimmel Live! August 16th, in addition to spending late nights in the studio, readying another short release for the fall and a slew of new music for 2022. Earlier this year, the group earned a new fan in Elton John, who called “Love and Hate in a Different Time” “probably one of the most seminal records I’ve heard in the last 10 years.”

“We need to give the early adopters more music,” Ellis says. “Now is the time.”