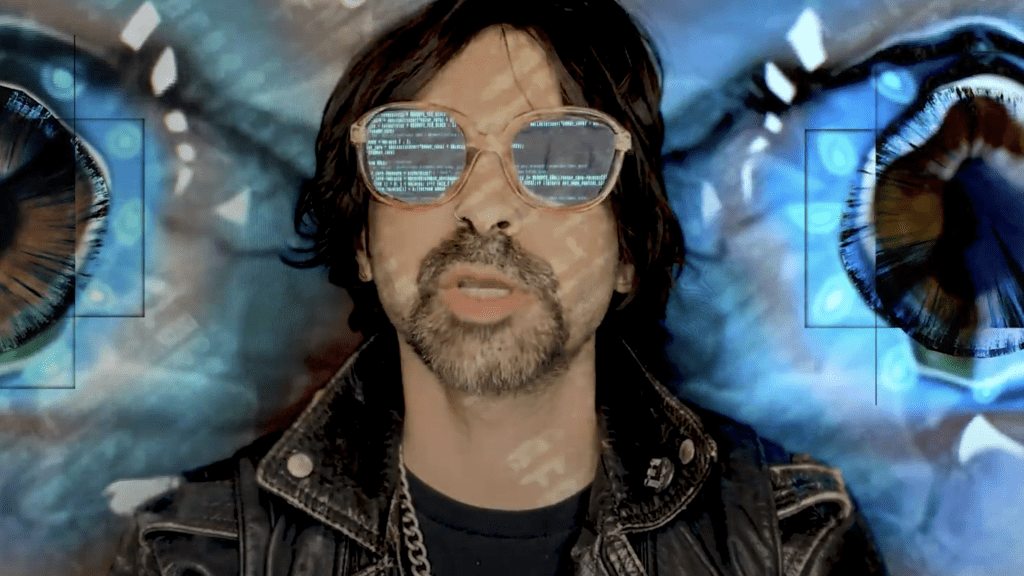

‘Grief is giving me this beautiful, deepening understanding’: Phil Elverum on loss, new love and his landmarks of US indie

For almost two decades, Phil Elverum’s life centred around performing and recording music. First as the Microphones and then as Mount Eerie, he had accumulated a catalogue of songs through which he made sense of his world, written with a diaristic honesty that won him a loyal following. But in July 2016, after the death of his wife, the cartoonist and musician Geneviève Castrée, a distraught Elverum began “rejecting my life’s work” and focused on single parenthood with their daughter, Agathe.

From his home in Anacortes, Washington, Elverum reflects on those darkest days. “Geneviève and I had both been artists, obsessed with our creative lives,” he says. “That was our focus, our devotion, our identity. But when she died, I asked myself: why had drawing at a table 16 hours a day or making all these dinky little LPs been so important to us? I questioned the existential value of art and music and poetry. These had been my tools to understand life. But when Geneviève died, they felt useless to me.”

In the months that followed, Elverum wrote and recorded a pair of albums, A Crow Looked at Me and Now Only, that helped make some sense of this incalculable loss, that reconnected him with art, music and poetry. Lost Wisdom Pt 2 reckoned with his short-lived marriage to actor Michelle Williams. Now, he returns with Night Palace, one of his finest albums – a sprawling, diverse, ambitious and perhaps surprisingly political record he says marks “a reset in my life”. Restlessly shifting between buzzing, melodic indie-rock, ambient passages, intimate folk-rock and inchoate blasts of black metal to deliver what he describes as a “multitudinous” sound, it finds Elverum “looking outward … I didn’t want ‘Phil Elverum’ to be a character in this record at all”.

Previously, he says, “all the songs I’ve written have been about what it’s like to be a human in the here and now, reckoning with this life”. This album examines his home in Washington “from poetic, metaphorical, almost spiritual perspectives”, and confronts the violence done to Indigenous Americans. At one point he sings: “This America, the old idea, I want it to die … Let this old world shatter and reform.”

“Modern life is pretty alienated from our past, our history, the brutality that undergirds this system we’re all benefiting from,” he says. “It’s an uncomfortable truth to admit: massive genocide happened here. But there are so many delusions here. If I’m to sing, to have a thing to say in this world, my ideal is that it diminishes delusions, it doesn’t enable them.”

As a teenager, Elverum had a singular focus on music. He fell under the spell of Canadian group Eric’s Trip, whose revelatory lo-fi jumble of indie-rock and acoustic experiments was, he says, “a world of its own”. Elverum wanted in to that world, and set up an old eight-track tape recorder in the back room of Anacortes record store The Business, whose owner was Bret Lunsford of indie legends Beat Happening. Late into the night, he composed his first cassette releases as the Microphones, “layering feedback and loops, just seeing what sound could do”.

Elverum left Anacortes for Evergreen State College in Olympia in 1997 – where riot grrrl had been forged at the turn of the 90s – but got his true education at Dub Narcotic Studio as apprentice to Calvin Johnson, leader of Beat Happening and founder of K Records, and immersed himself in the art of production. Meanwhile, the Microphones were gathering low-key heat thanks to 2000’s chaotic, lovelorn It Was Hot, We Stayed in the Water and 2001’s staggering, ambitious breakthrough The Glow Pt 2. He had developed a songwriting voice influenced by the “underground soap-opera” storytelling of Eric’s Trip; the “grounded, small-scale autobiography” of independent comics creators Chester Brown, Julie Doucet and Joe Matt; and the radical honesty of Sebadoh’s Lou Barlow. “It was about displaying your embarrassing fallibilities,” he emphasises. “An expression of punk idealism: ‘I’m no phoney – this is the real me.’”

The Glow Pt 2 was released on 11 September 2001, and Elverum promoted it with an inauspicious solo tour, “this weird, isolated odyssey across the southern states. There was aggressive patriotism and flags everywhere: racism, tribalism, the ramping up to war.” This darkness weighed upon him. During epic drives between shows, the soundtrack to Black Orpheus his only companion, he would pull over his station wagon to jot down new song ideas, experiencing “some kind of megalomania. I wanted to make something monumental, that would go down in history.”

These ideas became 2003’s Mount Eerie, a psychedelic, existential concept album that opened with five minutes of unaccompanied drums to simulate being in the womb, and climaxed with lyrics about Elverum being ripped apart by vultures and then reborn. It sounded like nothing else happening in music right then. But Elverum had no time to bask in Mount Eerie’s critical acclaim; he left Olympia in the wake of its release, deciding he would “move to Norway forever, despite never even having visited Norway. An on-again, off-again relationship was torturing me, and something had to change.” That Scandinavian winter, he put the Microphones to rest. “I needed to keep moving forward,” he says. “I didn’t want to get stagnant.”

His new vehicle, also called Mount Eerie, was experimental by design, its albums pursuing his every whim and concept – be that duetting with Julie Doiron from his beloved Eric’s Trip (Lost Wisdom), or embracing synthesisers (Clear Moon) or Auto-Tune (Pre-Human), or reimagining black metal (the thrillingly maximalist Wind’s Poem). He married Castrée in 2004, and in 2015 Agathe was born. Shortly afterwards, however, Castrée was diagnosed with inoperable pancreatic cancer; she died the following year.

In the immediate aftermath of this loss, Elverum felt aimless and bereft. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to write songs any more. I’m not a musician. I’m a parent, and that’s it.’ But it wasn’t long before songs started coming to me, out of habit, with no thought of my releasing them. Even as I was recording them, I told myself, ‘This is just for me.’” The songs addressed the loss of Castrée with characteristic, unforgiving honesty; on Real Death, he sang that death was “not for singing about … when real death enters the room, all poetry is dumb”. His family urged him to release these songs, but he remained hesitant. “I felt exposed in a way I hadn’t before, and that these songs were provocative, that maybe I would hurt people.”

Hurt who? “Strangers. I was using blunt language and just, you know, saying the thing. I never said stuff like, ‘She passed away.’ I said, ‘She died.’ For me, it was appropriate and respectful to not skirt around or use euphemisms. But I was afraid of hurting people by being blunt in this realm where people prefer the opposite of bluntness. I had a nightmare where I sang these songs and some stranger stormed the stage and punched me in the face. But in fact, the opposite happened. Nobody punched me.”

Elverum’s two albums responding to Castrée’s death – 2017’s A Crow Looked at Me and 2018’s Now Only – were starkly powerful and incredibly moving; they were greeted with deserved acclaim. Furthermore, they reaffirmed Elverum’s faith in his work. “I had felt like art didn’t help me,” he says, “but once that first, reactive period of grief passed, having this creative pursuit to navigate meaninglessness totally helped. It healed me, nourished me.” On his next album – 2019’s Lost Wisdom Pt 2, another collaboration with Doiron – he “deliberately tried writing more poetically”. The album is as autobiographical as those that preceded it, “but about a different phase of my life”. A year earlier, he had married Michelle Williams, moving with Agathe to New York to live with her.

“I made all these life changes,” he says. “But then it didn’t work, and I got dumped and had to move back home.” The more poetic approach was, in part, “because the person in these songs” – namely Williams – “was still alive; I couldn’t speak as freely about her, and felt more protective of her anonymity.” He sighs. “I can’t listen to those songs now.” They were written in “a period of hopefulness” during the break-up, “when I thought maybe understanding could be reached. And now I know that it can’t. It’s still a little embarrassing in hindsight, just because of how painfully it ended, and how abruptly. The trauma from that lasted a weirdly long time. It seems like [losing Castrée] should be a bigger trauma, but it didn’t require as much therapy.”

He has since started a new relationship. “I’ve been talking recently with my partner,” he says, “about the role of the past in one’s present, and about moving forward. I have a lot of layers of past; I have this daughter, and her mom died, and we have some of her things around. And I’ve got this new life, this new house I built, a new partner.” His next record, Microphones in 2020, attempted to make sense of all this: it was a single, album-length song that served as a treatise on memory and past and art, an examination of his lifelong project. After this unexpected final Microphones release, he “felt, conclusively, ‘the line is drawn – I’m freed from my past. I can move forward.’ And this new album, Night Palace, began with this unburdened, fresh starting point.”

Like much of Elverum’s work, Night Palace is by turns dark and redemptive, always unflinchingly honest, and occasionally deeply funny. Those lighter moments are often the most poignant; I Saw Another Bird revisits the grim omens that haunted A Crow Looked at Me, and this time sees only birds, suggesting the agony that inspired that album has passed. “I feel like I’m in the later stages of dealing with the loss and the grief,” he nods. “It’s not as raw. I’ve found peace. I get to live in the luxury of: I’m going to spend today looking at that cloud passing over the hill and thinking about what it means when a bird squawks at me. I take the responsibility seriously, to find something real and meaningful in this human experience.

“People say grief doesn’t end, that it’s with you for life and just changes,” he continues. “That’s true. I’m in a phase now where the role grief plays in my life is giving me this beautiful, deepening understanding of things. Like, yeah, a crow looked at me. OK? Well, I saw another bird. I see them all the time. It’s not a big deal.” He pauses, and smiles. “But it is a big deal, actually.”