Various Artists

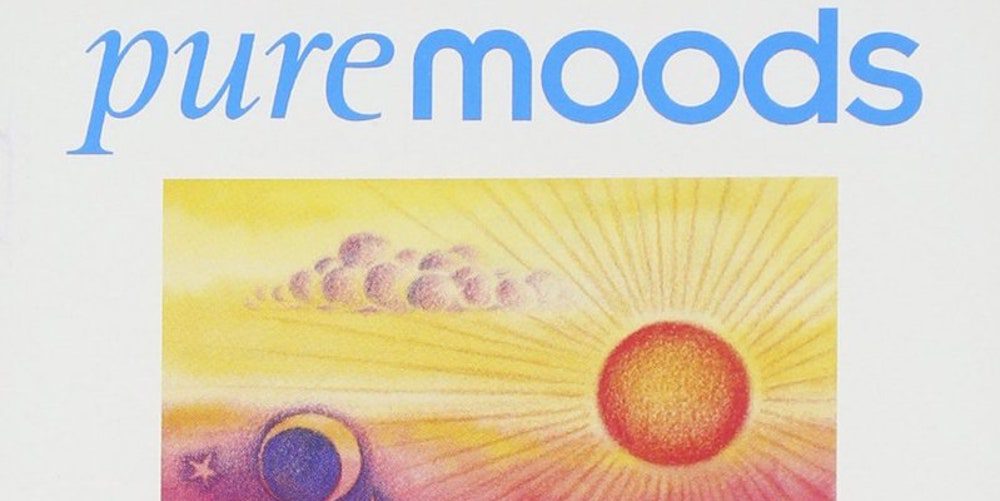

On weekday mornings, sometime between 1.a.m and 5 a.m., lawless fantasia used to appear on television like a good recurring dream. Today, the rhapsodies are duller, stricter, and more subdued, but in the ’90s, they came in the form of ads for phone sex lines, softcore porn, and low-resolution infomercials that sold the mirage of a life fantastic to a woozy after-hours audience. The colors were always saturated, syrupy, rich as cream; the tones sedate, misty, and mostly libidinal. Whether bored, sleepy, incapacitated, or horny, this tribe—routinely or accidentally—was well acquainted with the call of Pure Moods.

Unexpected, unbidden, and more or less unnecessary, Pure Moods is a piece woven with some wear into the silk of the popular unconsciousness. You may not remember hearing this work, but after watching the commercial, you might find yourself feeling that you’ve always known lines from its script. Swooning and naked in its pride, the 17-song compilation album, advertised in 60-second hallucinations disguised as infomercials, was a warm vat of music that we might today refer to loosely as “new age.” Its carefully selected tracklist—a mosaic made largely up of film or television scores, or trance remixes thereof—seemed engineered to induce a ridiculous sort of fugue state. For some, hearing the album might pang a Proustian memory of falling asleep on a familiar sofa. For others, it can suggest an intensely ambivalent mixture of pity and allure. Pure Moods’ essence is safe, formless, and mostly meaningless, like a piece of art hung in a bathroom. For me, and for many others, it felt like paradise.

Before the shadow of Bezos, before the Zuck, before, even, the contemporary comedy provided for us by the insidiously dippy Elon Musk, there was Sir Richard Branson. In 1970, 22 years before he would publicly weep while selling his record label/airline/mobile-phone/space-tourism conglomerate, Virgin, for over a billion dollars, the rugged and floppy-haired Branson invented the mail-order model of record distribution out of the usual entrepreneurial cocktail of luck and generational wealth. Twenty and lordly, then-helming his small but pop-savvy lifestyle magazine, Student, he noticed the UK’s Retail Price Maintenance Agreement—which kept strict restrictions on the saleable cost of vinyl records—had been quietly lifted. Seizing the sword of opportunity, he quickly took to the back pages of his paper to be the first to offer a good bargain. “Name any record you want,” his ad read, “and we’ll sell it to you 10% to 25% cheaper than anyone else.” A business was born. Branson’s arbitrage paid off well in an unwittingly fertile market, functionally reconfiguring a luxury product into a more petty-bourgeois pleasure. High off the fumes of his boon, he assembled a team from his editorial staff, bought a manor, refurbished it into a recording studio, and christened the effort “Virgin” in honor of his fumbling inexperience in the music industry. It would become one of the largest and most powerful record agencies in the world.

After the first ripe boils of the young label’s hardships had been lanced (Branson was noted for having “no musical taste whatsoever” until enlisting his avant-minded second cousin to arrange a roster of artists for him), Virgin enjoyed a mainstay on the tone and volume of music sales for many years. They held court, especially in the early ’70s, to a certain genre fit for the bookish, acid-dabbling Eurodude who read NME and dreamt of armfuls of warm Eurogirls who did the same. A river of German esoterica gave the label several releases by the psychotropic faerie proggers Faust (who were deftly marketed as “the German Beatles!”) and the rhinestoned scuzz of Tangerine Dream, but the pièce de résistance of Virgin’s inertia lay in a freaky slab of music by a shy 19-year-old composer named Mike Oldfield.

That an album with a title and sound true to the phrase “Tubular Bells” could have eventually sent the world into a mania for two 20-some-minute, mostly repetitive instrumental opuses of glockenspiel and honest gibberish is testament to the strength of Virgin’s aspirational animus. After hearing the mesmeric and thoroughly uncommercial music Oldfield had designed in the wake of a disturbing LSD trip, Branson backed his production efforts in full at the Virgin manor. It was clear that the future mogul yearned to head the most influential label in an industry that he knew incredibly little about. What he did understand, however, was that there was a vested, collective, and profitable desire for music that made audiences feel like connoisseurs of a higher order.

Cannily, Branson invited Britain’s leading tastemaker and radio host, John Peel, onto his houseboat for lunch, during which he played the entirety of Oldfield’s finished two-track, 49-minute Tubular Bells to the captive presenter. Miraculously, Peel adored the record and premiered it in full on his show. “One of the most impressive LPs I’ve ever had the chance to play on the radio,” he purred on his May 1973 transmission. Rolling Stone later called it “a debut performance of a kind we have no right to expect from anyone.” Tubular Bells would launch the Virgin empire by earning the label million-dollar financing from its investors, become the third-best-selling album of the ’70s in the UK, provide theme music for William Friedkin’s 1973 blockbuster, The Exorcist, and sell more than 15 million copies globally. Almost exactly 20 years later, Tubular Bells would lay at both the spiritual and literal centerfold of our Pure Moods.

The full ad for the U.S. release of Pure Moods lives on in accurate fidelity on YouTube, but it would be a shame not to recollect it for you here. First, a call bursts from a black screen. A quick time-lapse of a sunrise fades into a husky, lusty voiceover (“Imagine…a world…where time drifts slowly…”), which lays cozily across a shot of an autumn mountaintop. At least a dozen vignettes ensue. A woman spins in a woven dress as a unicorn gallops into translucence. A faraway man walks through a fast-moving river. The unicorn reappears, newlyweds gaze and grope at one another before a soulful kiss, waves crash onto a dusky beach, a swarm of hummingbirds eject from a cloud—each image t-boned into one another in an effort to inspire a feeling of chaotic, seductive fantasy, soothing by way of arousal.

First released as Moods – A Contemporary Soundtrack in the UK in 1991, the compilation was rebranded as Pure Moods upon reaching the U.S. in 1994. The slightly fatter American version contains songs that are as decadent and suggestive of Tolkienian lore and day spa imagery as the montage in the commercial, each composed by artists that, when written out, sound like a cast of villains and druids. There was Enya, Vangelis, the Orb, Enigma. Together, they formed a New Age Mount Rushmore, chiseled in lavender quartz.

These were tracks and artists never designed to be played alongside one another, tracks and artists, for all intents and purposes, mostly foreign to one another except in essence. Their clunky but satisfying cohesion can be attributed to the cataloguing done by the Virgin heads, who arranged the piece on a lark, “stumbling into the project” as an experiment to determine if an album could be successfully telemarketed and sold far before its release date. The model, deemed “a huge buzz” after selling more than 2 million copies prior to its formal drop, would be replicated five times over with a tetralogy of sequels in the releases of Pure Moods II-IV. Later, it would fuel a variety of spinoff flavors, like Gregorian Moods, Christmas Moods and Tranquil Moods: The Ultimate New Age Collection. (I will freely offer that these should be sold as a box collection, titled, simply, “Mood Ring.”)

No claims were made over precisely what sort of mood Pure Moods would put you in, but the album summoned a particular soul of Virgin’s experimental curios and left-field aberrations that signaled a certain taste, ease, and class of listener. It was something like a lifestyle brand touting self-care avant la lettre. Suitable for the essential-oiled and candlelit bath, the head shop, or for popping into the cassette deck of your Corolla on a summer’s night with the windows down and your children asleep in the backseat, Pure Moods arranged a prefab state that, for the listener, may have summoned a feeling they didn’t know they needed. Likewise, for Virgin, Pure Moods was something of a sample platter made in quiet tribute to the unexpected blessings in their own roster: the artists, tracks, and rogues that had clinched the success of the label in stupefying spades.

At the spine of both the UK and U.S. versions of the album lives the baroque jangle of “Tubular Bells” (though excerpted from its original sprawl to a reduced-fat 4:58). Flanking “Bells” are tracks from Enigma, a louche and late-stage ’90s-era cousin of Oldfield’s success. “Sadeness (Part 1),” the first Enigma single, is a porny, breathy, breakbeaty song, with Gregorian chanting giving way to a French voice pining orgiastically for the 16th-century erotic writer, Marquis de Sade, atop a downy bed of trip-hop. It somehow defies both anarchy and order, any sense of convention, and the usual formula for anything resembling commercial success. Yet, beginning in 1990, it lived on the Billboard charts for five unbothered years, reached the Top 10 in several countries, and made Enigma the most successful act signed to Virgin at the time of its release. (Unintentionally, the Gregorian chanting endemic to the track created a global hunger for sacred Latin monophonic music: In 1994, an unrelated album titled Chant from three dozen Benedictine monks living in a Spanish monastery went double-platinum.)

True to their title, Enigma remained heroically and consumingly atop the charts for the majority of the ’90s. “Return to Innocence”—whose aboriginal Taiwanese vocalizations blast at the top of the commercial, responsible for waking thousands of half-asleep American citizens on couches—is a glamorous smoothie of pseudo-erotica, a treatise on nostalgia and self-help. Seemingly custom-made for the proto-Y2K fetish for exploring one’s attitude with slogans across graphic t-shirts, its first four lyrics are just words (“Love…devotion…..feeling….emotion”) both inspiring and completely drained of meaning, at once empty and rich. It enjoyed a No. 1 one position on the charts in over 10 countries.

Non-Virgin releases on Pure Moods share the twin tenets of mild conceptual lunacy paired with baffling commercial success. There’s Enya’s immortal “Orinoco Flow (Sail Away),” which, upon its release, the Los Angeles Times scoffingly noted as part of an album filled with “nothing more than unusually windy New Age music.” “Orinoco Flow” is, in fact, an island archipelago of a song, with choral arrangements as lush and fabulous as the remote wonders it promises. It seems to give off its own aromatherapeutic odor and made Enya—a woman who does not tour, who never has toured, and whose perfectly inverse ratio of near-total reclusiveness and global omnipotence inspired an entire phenomenon known by business students the world over as “Enya-nomics”—one of the wealthiest and best-selling musicians alive today.

There’s the four-minute throb of “Oxygène Part IV,” courtesy of one Jean-Michel Jarre, who once bore ownership of the Guinness World Record for hosting the world’s largest concert (3.5 million in Moscow, 1997). DJ Dado, an agent of chaos, remixed the theme from The X-Files into his “Dado Paranormal Activity Mix,” ascending an already astral, imminently whistleable piece of art into the Burning Man mesosphere of dream trance (a top 10 hit for weeks across Europe). Kenny G, the saxophonist known in most minds as the human incarnation of a scented candle, contributes a satiny number titled “Songbird,” a song that became the first instrumental to reach the top 5 of the Billboard Hot 100 since the “Miami Vice Theme” by Jan Hammer (who is also featured on Pure Moods).

It’s no surprise that so many of these tracks were either born or retrofitted into movies and commercials. From Karl Jenkins’ “Adeimus” (now known as part of an indelible Delta Airlines spot), David Byrne’s “Main Title Theme from The Last Emperor” (self-explanatory) even to David A. Stewart and Candy Duffer’s silken, sax-laden “Lily Was Here” (of the 1989 Dutch film, De Kassière, later to become a mainstay of the Weather Channel “Local on the 8’s” music) these were spectral mood-pieces, if not tailored for, then entirely befitting of, calibrating emotion. When divorced from the screen, scores take on new life when soundtracking yours.

But an album that capitalizes on tracks that would serve as well as closing-credits for a lovesick drama as they would in an airport bathroom does not, necessarily, a serious album make. Even without looking at the melty watercolor cover or hearing the title of the compilation, the songs summon the solace endowed by inspirational posters and cruise brochures that now feel bathetically out-of-touch: blue horizons freckled with soaring birds, pistachio mountaintops, forests of fluff and fungi, images of women with their hair thrown back in smiling rapture. Are these parodies of paradise, or can we see them in earnest? The commercial unhelpfully adds that the album is delivered “direct from Europe,” wherever or whatever that may be.

If you, like I, have struggled manfully to crack the riddle of whether the album is glib, good, or good in its glibness, the idea of camp may be a sound starting point. As Susan Sontag details in her 58-point treatise from 1964, camp is work characterized by a sort of “seriousness that fails.” Or, a unique “spirit of extravagance [that] cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much.’” That too-muchness—from the commercial’s art direction to its deliciously sleazy voice-over, promising that this album was specifically “for your way of life”—was enough for mine, and for hundreds of thousands of others. Pure Moods peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard chart the week of July 26th, 1997, the same week the Men in Black soundtrack secured first place.

An inspired and perfect choice, then, that Pure Moods begins its downtempo descent with Angelo Badalamenti’s “Theme from Twin Peaks,” that totalizing Lynchian ballad of too-muchness. Regardless of whether your first encounter with the music was within the hundreds of scenes it was deployed in during the television series, in the later-lyricized Julee Cruise version, titled “Falling,” or, even, within Pure Moods, Badalamenti’s score from a show that—like the album—embodied mesmeric alternate realities, sentimental chintz, and a strangely narcotized, palliative hopefulness, sealed the work tightly with a sad, bassy kiss.

For everything that Pure Moods is, one thing is certain: Pure Moods is not kidding. Pure Moods aimed to sell the awe and wonder of music’s ability to change you. It is work that is genuinely, and for better or worse, peddling you a vague miracle. It is quietly saying that you will feel good for having listened to it. Even if it reeks of patchouli and a joke now, it also reeks of something like purity.

Even those most irony-poisoned among us can wrap ourselves around the fullness of Pure Moods as a pop object that’s completed its natural tour of meaning: a curio first taken in earnest, then as a joke, now as a museum fixture that holds both forces in its heart at once. It also illustrates the great life cycle of art’s journey through critical response—how spectacles are typically born as novelty, laid to rest as cliché, and resurrected as nostalgia.

Watching the ad for Pure Moods today can impart a sort of joyous nihilism by laying bare the architecture of the more complicated—but no less fantasy-enabling—advertising so inherently part of our lives now. And, in an hour when everything feels alien and existence slippery, falling in love with Pure Moods’ lawless pageantry is worth any mild cognitive dissonance it suggests. “People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing,” goes Sontag, again. “They’re enjoying it…it is a tender feeling.”

I grew up watching infomercials with the focus of an obsessive. Longform ones, like that of the especially good spot for the Magic Bullet blender (a full 30-minute, eight-actor orgy of disbelief), or that of the Xpress-Redi (in which two people praise a countertop griddle) were especially rich for their steeply-sloped story arcs, climaxing in money shots of satisfied men and women leading their lives with new, happy ease. These half-hour-long paeans to kitchen appliances were absurd moments of absolution; they worked like slow-acting pills against the usual symptoms of childhood melancholy. Their taglines and promises buried themselves inside me like hymns or worms. For the child who slept belly-down in front of a television nearly every night, exhausted by the glow of a screen, these moments felt like satisfying surrender to a particular sort of commercial rapture.

And this is what Pure Moods inspires—rapturous, wild, ridiculous satisfaction, each song over-indexing on its unspoken bond to bring fantasy to an otherwise quotidian life. Like the seconds before losing consciousness, it re-created a floating, near-delirious state as image and song wrapped each other in a duvet of chloroform and melatonin. To so many, Pure Moods guaranteed a feeling so total, so rich, so sedative and decadent, that it approximated, then beget, real beauty. The miracle was the point. To see salvation suddenly offered to you—a proposal to make life easier, more fantastic, purer—was a bargain at $19.99, rush shipping notwithstanding.