Angélique Kidjo Is Tapping the Next Generation to Speak Truth to Power

One day in 1992, Angélique Kidjo walked into a magazine editor’s office and found herself being introduced over the phone to one of her all-time favorite artists.

“Someone said, ‘Mrs. Kidjo, Mr. Brown wants to talk to you,’” she recalls. In stunned disbelief, she replied, “Yeah, and I’m Mother Teresa.” But it really was James Brown, the Godfather of Soul himself, asking to talk to her.

“I almost dropped the phone,” she continues. “He was speaking, and I couldn’t understand, so I started singing. He picked up the song and I would do the bassline, I would do the guitar, I would do the drums — just like, crazy stuff.”

It’s just one of a sea of stories of Kidjo meeting and collaborating with all-time greats across generations. Over the course of her three-decade long career, Kidjo, 60, has dipped into the vast well of legendary artists and performers across the black diaspora — taking inspiration from South African artist and activist Miriam Makeba, Cuban salsa icon Celia Cruz, Aretha Franklin, and many more. She has collaborated with many of the African continent’s greatest legends, from the bluesy stylings of Boubacar Traoré to Manu Dibango’s Cameroonian jazz saxophone lyricism.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

After a storied career of paying her respects through endless innovation within black sonic canons, she has the distinct honor of being exalted on the level of the artists she adores, with young artists throughout the international black community often referring to her as “Ma” or grande soeur. Now, she is paying that respect forward wherever possible — including rounding out her latest album, Mother Nature, with collaborative features from emerging young artistic voices in the African continent and its diaspora, ranging from Nigerian star Burna Boy to Atlanta hip-hop duo Earthgang .

“With my work, I’m always in my continent,” she says, explaining that she’s learned a lot about emerging contemporary youth culture via her work with UNICEF and her own Batonga Foundation. “They want something completely different…They aren’t playing, man. They’re huge stars in their own right, and making much more money than they can make in America or anywhere else.”

This perspective informed Kidjo’s remarks on the 2020 Grammys stage in Los Angeles, where she won Best World Music Album for Celia — a project that revisited the salsa great’s defining tracks and amplified the distinct West African percussive and spiritual foundations of the Queen of Salsa’s music. “Four years ago on this stage,” she said, looking out to the crowd from the podium, “I was telling you that the new generations of artists coming from Africa are gonna take you by storm, and the time has come.”

“That’s what I’m trying to tell them at the Grammys,” she says now. “I’m saying, y’all are gonna stop looking at Africa through your really narrow-minded lens. Things are happening — and these new generations, they ain’t afraid of no challenge at all.”

At the time, Burna Boy was also nominated for his critically lauded project African Giant, which included Kidjo’s contributions on the powerhouse track “Different” alongside Damian Marley. It’s a moment that was facilitated by a call from none other than Burna’s mother and manager, Mama Burna, who notably accepted a BET Award on his behalf in 2019 while stating, “every black person should please remember that you were Africans before you were anything else” — a sentiment that goes hand-in-hand with Kidjo’s personal and professional ethos.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

“I went and visited him after the Grammys and we talked,” Kidjo says. That conversation led to a standout collaboration on her new album that Burna supplied, called “Do Yourself” — an immersive collaboration with the young star, known for his anti-colonial imagery and messaging, that serves as a call to action for African self-empowerment and self-determination.

Mother Nature serves the dual purpose of both inspiring the masses looking for guidance towards the future, and connecting with the next generation of artists who have had the privilege of following in the footsteps of Kidjo and her contemporaries while blazing trails of their own. Nigerian artist and Banku music pioneer Mr. Eazi’s contributions to the project in the track “Africa, One of A Kind” are anchored by a dynamic sampling of Salif Keita’s “Africa”, a song that Kidjo originally planned on performing in a curated Carnegie Hall series in March 2020 honoring 1960’s “Year of Africa” alongside Manu Dibango, before Dibango tragically passed from Covid-19. “Dignity,” a collaboration with Yemi Alade, is a direct response to the youth-led uprising against Nigeria’s infamous Special Anti-Robbery Squad. “Free and Equal,” whose title directly plays off of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is a call to the entire black diaspora, brings in Zambian artist Sampa the Great, whom Kidjo discovered by watching her Tiny Desk Concert.

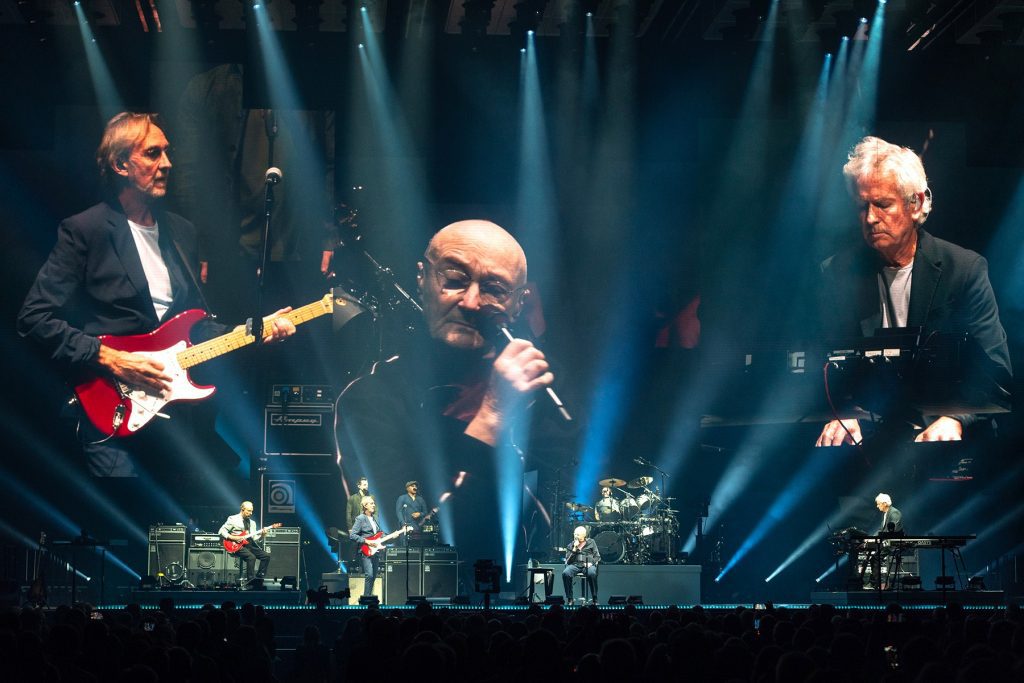

Angelique Kidjo with Burna Boy.

Jean Hebrail

Kidjo also harkens back to her homeland of Benin with “Omon Oba,” bringing in young Beninese musicians to continue the work of building her personal story into a greater practice of reverence. “Salif [Keita], myself and the young generation, we just have to continue that chain,” she says. “That chain allowed us to know who we are and where we come from — you might not know where we’re going, but we definitely know where we can go back to.” And go back she does, reshaping the seminal revolutionary Congolese classic “Independence Cha-Cha” into a melody that honors the ongoing liberation fights throughout the continent in both sentiment and name.

Kidjo’s coalescence of personal and political is most evident in the title track, which tells the story of ancestral struggles that have played out with the African diaspora, emphasizing how those struggles manifest in climate and environmental justice efforts, particularly in the midst of the Covid pandemic. “If you don’t want to weigh people down, make them dance — make them dance and listen,” she says. “All of those conversations are very deep conversations to have, and I want people listening to the album to have those conversations themselves by listening to the song.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

What provides the album with its gravitas is its emphasis on connection — not just between the older generations and young upstarts, but between cultures and places. She connects the Yoruba legacy and musical stylings with its descendants in present-day Benin, reinterpolates the traditional variété française style of ballads with the sharp edges of West African inflection and percussion, marries electronica with traditional continental rhythms, and injects calypso, kompa, and dancehall musical phrasings into contemporary Afrobeats production and alt-R&B with ease.

Since the Trilogy album series she began in the late 1990s (Oremi, Black Ivory Soul, and Oyaya!), Kidjo has made a point of acknowledging African-American cultural production and its prominent position in the greater contemporary diasporic fabric. For this album, she tapped the Roots’ James Poyser to work on her track with Earthgang, whose distinctly melodic and staccato lyrical approach integrates seamlessly with a Congolese-influenced refrain.

Asked for her perspective on her esteemed status amongst peers and idols, Kidjo simply states, “It’s just a matter of humility.” She’d rather defer to a position of service to her people, the music, and the various inspirations that compel her to create. She is happy to see the ways that conviction has empowered younger artists on the continent to pursue their own sensibilities without reservation. “I do it because that’s the person that I am, and I’m not expecting anything in return. But if, through my work — my integrity and my hard work representing my continent for so long, taking so much heat, so many slaps — it gives them the strength to be who they want to be today, then I think part of my job is done.”

Having represented such a large diaspora of black people on the world stage is not a gift that she takes lightly, and it is a core part of her mission to transform topics that people find to be cerebral and abstruse into engaging musical storytelling. On Mother Nature, she uses joy and pride as transcendent tools of empowerment. A self-designated “Daughter of Independence” — Kidjo was born on July 14th, 1960, two weeks before Benin declared independence and in the same year as 16 other nations’ establishment of autonomy — she sees the pandemic and ongoing liberation crises as urgent calls to action. Community is more critical than ever before, and her mission to inspire change and speak truth to power has now been re-centered in collective work and trust, embracing the impact that her work has had on the younger generations.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“The best way to tell our story is us,” she says. “No one can tell it for us. You want to be part of this train, or you just want to be a bystander? You want to jump in it? We need collaboration, we need partnership — we don’t need your help.”

In Kidjo’s world, your place of birth in the black diaspora is irrelevant: Everyone should be able to tap into a shared pride in a greater African legacy, and the way that legacy is expressed in its multitude of iterations. “Don’t be afraid of no one,” she adds, “because where you come from is great. Period.”