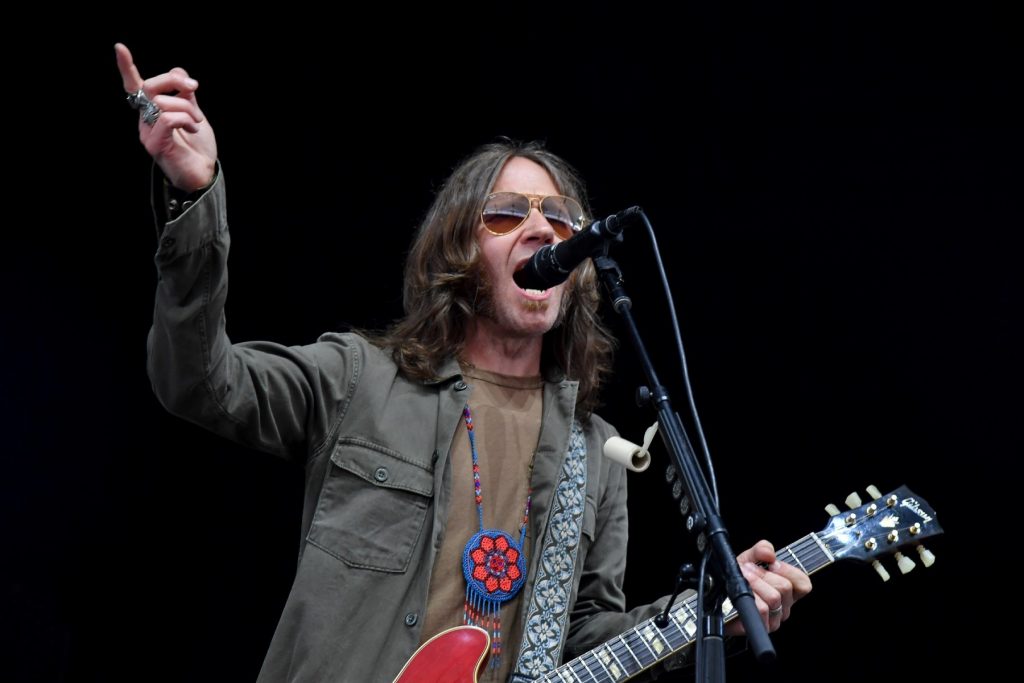

Blackberry Smoke Mine the Bible and Their Georgia Roots on Introspective New Album

There’s a simple acoustic ballad called “Old Enough to Know” on Blackberry Smoke’s new album You Hear Georgia that captures that bittersweet moment when experience collides with age. Just when you’ve figured out the tricks to living life, you’re already past the point where they can help you.

“They don’t tell ya till you’re old enough to know” sings Blackberry Smoke’s Charlie Starr in the melancholy song, written with frequent collaborator Travis Meadows.

Two decades into their career, Blackberry Smoke may not be at that juncture just yet, but they can view it on the horizon. Calling from Syracuse, New York, during an off-day on their first proper tour since the start of the pandemic (they played drive-in shows and socially distanced gigs in 2020), Starr is looking forward to that day’s band field trip: walking the local mall.

“It used to be, ‘Alright, man, let’s go out tonight to the strip club,’” he says, recalling more hedonistic times. “Now it’s, ‘Dude, there’s a Whole Foods across the street!’”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Blackberry Smoke still play songs about fast women and too many beers, but these days, Starr, 46, is far more concerned with introspection. The songs he writes, most often by himself, can reveal his untapped feelings about his father, acknowledge past backslides, or even draw on the biblical teachings he absorbed in Sunday school as a kid.

The Bible is a wellspring of lyrical ideas for Starr, something he bonded over with Alice Cooper, one of his heroes, during a 2012 interview on the shock-rock pioneer’s radio show. “I knew going into the interview that he’s the son of a minister, and he touched on that immediately,” Starr says. “He was like, ‘OK, I see what you’re doing. I see some of these biblical references. I do the same thing.’ We’ll always have that to draw from, as far as imagery, because what’s more powerful, right?”

In the New Orleans shuffle “Hey Delilah,” Starr unites the secular with the sacred, updating the Bible story of Samson and Delilah as a tribute to a girl with “a wild streak a mile long” who “helps me sing a dirty song.” Like the biblical Delilah, she double-crosses him too.

“That story always fascinated me when I was a kid because Samson had long hair and he was the strongest person in the world,” he says. “I remember getting really frustrated like, ‘Wait a minute, don’t tell her what gives you your power!’ But because of love or lust, he finally gave in.”

Formed in Atlanta in 2000, Blackberry Smoke are a Georgia band through and through. On 2016’s Like an Arrow, they recruited Gregg Allman, synonymous with the soulful, humid vibe of the Peach State, for the song “Free on the Wing,” one of Allman’s final recorded performances. But on You Hear Georgia, they amplify their roots right in the title of the LP. You Hear Georgia marks the band’s first time working with Dave Cobb — the Grammy-winning producer of Jason Isbell and Chris Stapleton, and a fellow Georgian — and it was Cobb who encouraged Starr to write the title track after he heard him playing the riff during a studio break.

Starr finished the song with Dave Limzi (whose band the Four Horsemen released a Southern-rock cult classic in 1991’s Nobody Said It Was Easy) and landed on the record’s title in the process. “It kind of feels like the album really is a tribute to the state of Georgia, but it wasn’t intentional,” Starr says.

Starr and the band — drummer Brit Turner, bassist Richard Turner, guitarist Paul Jackson, and keyboardist Brandon Still — expanded their lineup with slide guitarist Benji Shanks and percussionist Preston Holcomb and cut live on the floor at Nashville’s RCA Studio A. As a result, You Hear Georgia sounds downright huge.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article2″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“I said to Dave, ‘We’ve been playing a lot of gigs as a three-guitar band and with percussion,’ and that’s what he wanted to capture,” Starr says.

The big band lets loose on “All Over the Road,” the most rambunctious track on the album. Based on a true story about a guy Starr knew who drove 200 miles every weekend from Panama City, Florida, to Opelika, Alabama, to see his girlfriend, the song plays like Dave Dudley’s trucker anthem “Six Days on the Road” after a hit of meth.

“He was working all week for a construction company, literally digging ditches, and then Friday afternoon when he got off work, he would drive to Opelika, Alabama, to be with this girl. Then he’d drive all the way back on Sunday,” Starr says. “He’d always tell me, ‘Man, I got a radar detector and I just put the hammer down.’ That’s where that came from.”

But if “All Over the Road” is Starr celebrating spontaneous impulses, “Old Scarecrow,” which directly follows it and closes the album, is him probing the past. Starr wrote the music with Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Rickey Medlocke, but the lyrics, at first defiant and obstinate (“I ain’t losing sleep over your opinion,” it begins) become vulnerable and personal.

Starr imagined the character in the song as an old farmer who lived through the Depression and World War II but is struggling to make sense of today’s world, specifically its technology and divisions. He’s unconcerned with the culture wars and wants to simply go about his business.

“He’s a good man and he’s looking at the judgment that happens online. It’s so very in the now, you know?” Starr says. “And he’s like, ‘I don’t care about all that. I don’t care what you think. I just want to be here and live my life and do what I do and take care of my family. I love my family. I love my friends. And if you don’t like me, then goodbye.’”

Starr realized afterward that he was writing about his dad, the man who first introduced him to bluegrass and gospel. The elder Starr wasn’t much into rock & roll, and still isn’t.

“I didn’t really see it when it pen was going to paper, but that’s him,” Starr says. “He taught me good things, taught me to not hate people, don’t judge people. He’s very religious, he’s very Baptist, and I never heard him say a bad thing about anybody.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid-articleX”,”mid”,”in-articleX”,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“I ain’t ever gonna change my ways/make my stand for the rest of my days,” Starr shouts in “Old Scarecrow.” It’s the final line of You Hear Georgia and an appropriate couplet on which to end the album. Twenty years down the road from their formation, it’s Blackberry Smoke’s credo.