Dawn Richard’s Precious and Precarious New Orleans

“We went from homeless to limitless, y’all,” Dawn Richard coos sweetly on her sixth studio album, Second Line. That lyric neatly encapsulates her trek through the music industry. It also tells a story about the place Richard comes from. The album gets its name from the parades of dancing revelers that follow brass bands down New Orleans streets, often marking new beginnings, like weddings, or bittersweet endings, like funerals. “I wouldn’t have survived as an artist if it wasn’t for what I came from,” Richard says. “My city is based off of survival. We’ve been through so much, yet we dance through it all, even death.”

This summer, not for the first time, Richard watched her hometown hurt and rally as Hurricane Ida — the powerful storm that hit southern Louisiana precisely 16 years after Hurricane Katrina — killed at least 30 in the state and caused up to an estimated $64 billion in damage nationally. Richard, who had fled to Los Angeles for safety, witnessed neighbors back home in New Orleans lending tools and sharing resources in text threads. “I’m still asking people to donate to Habitat for Humanity, to things like that,” she says. “People think that once natural disasters happen — once it’s over and people come back home — that’s it. But the truth is, there are a lot of things that come with the aftermath.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

The trauma left behind by Hurricane Katrina, she explains, informed her family’s evacuation plans this year. Rattled by memories of 2005, Richard opted to get as far as possible from the storm, hoping she could convince her mother and father to join her in L.A. Instead, her parents drove to Dallas to wait out the storm, wanting a self-sufficient route back to their suburban New Orleans home. “My mom and dad were willing to go through craziness to make sure that they could get back home just to see if their house was still there,” says Richard. “The way they handled their trauma — they needed to set eyes, because the last time we went back, there was nothing, we had no home.”

In the summer of 2005, Richard was best known as a contestant on the third season of the Diddy-helmed MTV reality show Making the Band, filmed in New York City. Before the final five young women were chosen for Diddy’s girl group, Richard went home to New Orleans and was soon met with Katrina’s devastation. She spent three weeks living in a car with her parents, before eventually being summoned back to New York to take her spot in Danity Kane, named for a comic-book character Richard created.

Crushed and jobless after Danity Kane ended four years later, Richard joined her family in Baltimore, where they had relocated after Katrina. She later reunited with her Bad Boy label boss as a part of the trio Diddy-Dirty Money, which released one studio album in 2010 before disbanding as well. In 2015, a decade after the hurricane, her family returned to New Orleans, and in 2019 Richard joined them there for good. “We never wanted to leave,” she says. “My parents had retired, so we all went home. It was the best decision we ever made.”

All these years later, Richard is proud to have mostly escaped the music business’s New York-to-Los Angeles orbit, a move that she credits with helping her make the “electro-revival” album of her dreams. A smooth amalgamation of dance and electronic music sounds from New Orleans bounce to Chicago footwork and D.C. go-go, Second Line celebrates the resilience of her city, her personal tenacity, and the inextricable link between the two.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

For Richard, living in New Orleans has come with a recommitment to her art and her joy. “I’m not trying to have a national career,” she says. “I want to be happy. . . . I was in New York and L.A. and I still wasn’t big nationally. I was in two big multimillion-dollar groups; it didn’t help me none. It didn’t. So why not be in a place that inspires me and try it a different way?”

Her 2019 LP, New Breed, explored her father’s NOLA roots by sampling his funk band, Chocolate Milk, and drawing on the Mardi Gras Indian aesthetics of his ancestry. Second Line, too, drips with New Orleans pride, from the way she channels the city’s distinctive accent in lead single “Bussifame” to her majorette garb and choreography in its video.

One of the album’s clearest throughlines to the city is “Pilot (a lude),” a tribute to bounce artists like Big Freedia, Katey Red, and Messy Mya. Richard grew up surrounded by the upbeat dance music. “If a DJ is there, bounce is happening,” she says. “There’s no inappropriate age for bounce. You’re four years old, the Easter Bunny come? Bounce. Santa’s out there? Bounce. Bounce is played all day, every day.”

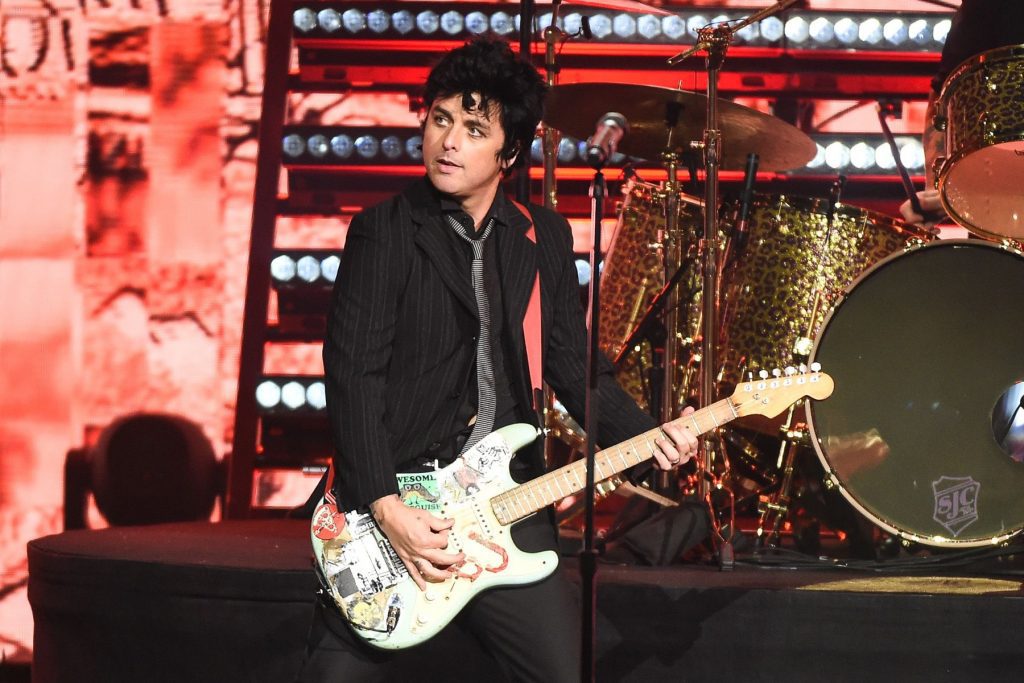

Dawn Richard at the sculpture garden in City Park, New Orleans.

Akasha Rabut for IndieLand

New Orleans is synonymous with dance to Richard, who cut her teeth at the dance studio her mom, Debbie Richard, ran until losing it to Hurricane Katrina. Richard displays her sharp skills in her music videos for “Pilot (a lude)” and “FiveOhFour (a lude),” both of which were shot in New Orleans’ City Park. “The moss trees and just the bigness, the bayou and the ducks and the swans — it’s such a beautiful representation of the city,” Richard says. “If your parents want to show you heaven but they don’t have a lot of money, they show you City Park.”

Debbie Richard’s story is part of the narrative glue that holds Second Line together, with conversations between mother and daughter serving as transition pieces. In one, Debbie tells Dawn that she was brought to New Orleans by her parents at two years old, from New Iberia, Louisiana, a rural town roughly two hours west. “People speak broken French, you have to walk to school, there’s miles before you have a neighbor,” Dawn says. “Bayou country.”

New Iberia also bore a dark history for Debbie, who grew up in a violent home there, her daughter says. “You can hear my mom’s strength through how she sees the second line, how she sees love, how she sees what a Louisiana girl is. New Orleans became her savior. If you’re hurt and you leave, New Orleans is hope.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Growing up, Richard loved seeing alternative bands when they came through town (Green Day and Alanis Morissette were her first two concerts). As a young girl, she was often the only act in talent showcases performing the electro-pop music she’s perfected as an adult. Now, she sees the arrival of Buku Music & Art Project, a festival founded in 2012 to celebrate electronic music, as an indication of how tastes and opportunities in her hometown are expanding. She’d like to see New Orleans flourish more, into a festival hub that caters to Black music more expansively. “I would love to see us have a Coachella vibe, where we embrace the Black DJ, the Black rock band, the Black heavy metal band, the indie kids,” she says.

Now that her life as part of the music industry’s biggest commercial-pop machines seems behind her, Richard is focused on bringing people and resources into her world in New Orleans. “With this album, the hope is to show people artists like me exist here, and we were born and raised here, and we’re not neglecting the heritage,” she says. She hopes to serve as an example for newer local artists, so they’ll feel less pressure to leave the city to succeed. “The moment I got in my career, I was homeless,” she adds. “So this is the first time I’ve been able to touch my city as an adult, musically, the way I’ve always wanted to, to get into the soil.”

In the aftermath of devastating storms, Richard is also thinking about the ways New Orleans needs protecting. “We are a musical city that most of the world wants to visit,” she says. “If you want to preserve that, then we have to start having the conversation that global warming exists and we are a product of it. If we want to continue to have those festivals and continue to have that art, we need to start paying attention.”