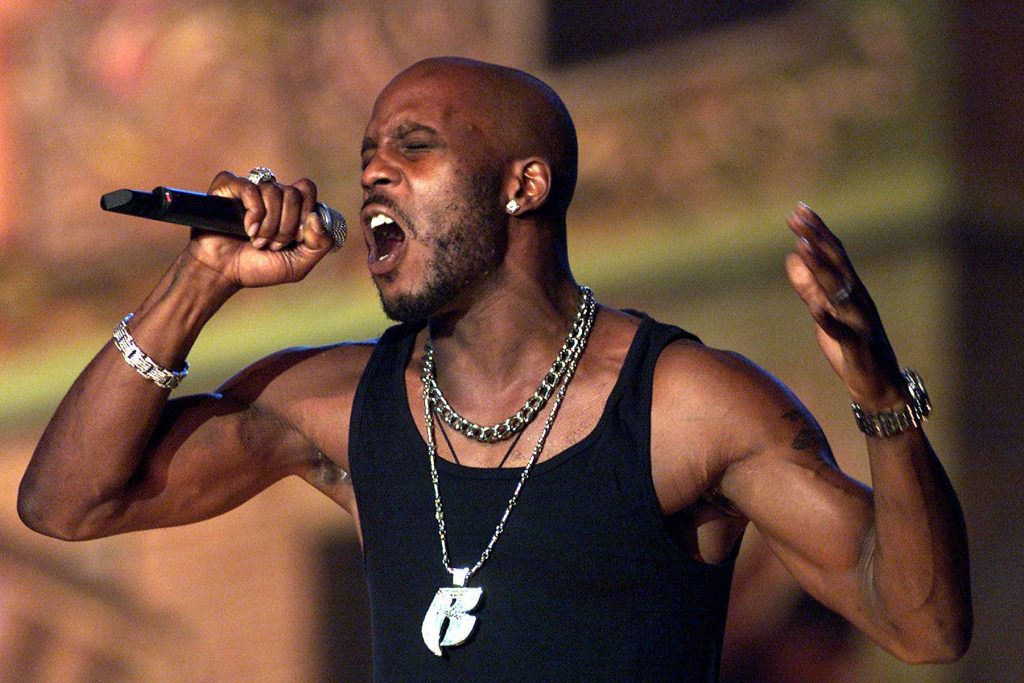

DMX: 16 Essential Songs

DMX was a larger-than-life force in rap music at the turn of the millennium. The Yonkers, New York, rapper, who died April 9th at age 50 after being hospitalized with a heart attack days earlier, burst onto the scene in the Nineties with one of the most distinctive voices on the radio — a commanding presence on the mic, from his earliest guest appearances to the five straight multi-platinum albums he released starting in 1998. Effortlessly balancing raw charisma with hit-making savvy, X had a major impact on the sound and direction of an era in hip-hop, and the catalog he built stands as a landmark of passionate, profound performance. Here are 16 of DMX’s most essential songs.

LL Cool J featuring Method Man, Redman, Canibus, and DMX, “4, 3, 2, 1” (1997)

Produced by Erick Sermon, LL Cool J’s street hit from his 1997 album Phenomenon is not only famed for inaugurating Def Jam’s late-Nineties “Survival of the Illest” era, but also for sparking a subsequent war of words between seasoned vet Uncle L and brash newcomer Canibus. Meanwhile, Method Man and Redman ladle the cut with punchlines, and DMX uses his verse to shout out energetic ski-mask threats. “Do you value your life as much as your possessions?/Don’t be a stupid nigga, learn a lesson/I’m gon’ get you either way! And it’s better to live/Let me get what’s in your sock, ‘cause it’s better to give,” he instructs. This year, as news spread of DMX’s hospitalization, LL Cool J reminisced on Twitter: “Today is 4/3/21 — it’s only right that we celebrate the talent and genius of my brother DMX on the 4, 3, 2, 1 song. We love you X get well fast.” — MR

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

DMX featuring Sheek Louch, “Get at Me Dog” (1998)

Many DMX fans don’t realize that before he seemingly emerged as an overnight sensation, the Yonkers rapper struggled to crack the industry for years, leaving a failed Columbia single deal (1992’s “Born Loser”) and random guest verses in his wake. No wonder that his first major hit found him portraying the life of a hungry criminal who hustles for survival. “I rob and I kill, not because I want to, ’cause I have to,” he raps over a pulsing Dame Grease beat that makes excellent use of a B.T. Express disco-funk sample. “’Cause nowadays, gettin’ by is nothing more than an occasional meal and gettin’ high.” He punctuates his words with yelping barks, and the track simmers with uneasy, menacing excitement. Complete with an assist from Sheek Louch from the Lox on the chorus, “Get at Me Dog” kicked off DMX’s 1998 — a Year of the Dog if there ever was one — with a gold-selling top 40 hit. — MR

DMX, “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” (1998)

A master class in how to ride a beat. No one has ever sounded better over Swizz Beatz’s keyboard loops — it took a rapper as charismatic as DMX to imbue those Casio presets with such physical presence. “I wrote it in 15 minutes,” he recalled in a 2019 interview. “I actually didn’t want to write it. I didn’t want to do that song. The beat was simple and repetitive. So many other songs had so much substance, and this song was like, fucking ABCs, like elementary.” That simplicity turned out to be the song’s secret weapon, giving him more room to flex, alternating gruff-talking threats and half-sung melodies with crooked-smile punchlines. (“Oh, you think it’s funny?/Then you don’t know me, money.”) This song was omnipresent on hip-hop radio that year — a self-declared anthem that really was one, and a loud and clear signal that a new rap superstar had stopped, dropped, and opened up shop. — SVL

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

DMX, “Prayer (Skit)” (1998)

DMX came from the era of skits on rap albums, and on his 1998 debut, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot, he offers up an upfront prayer that serves as a functional mission statement for his entire career. X’s music was always rooted in faith, and his work offers a reminder of religion’s transformative power when not being weaponized for politics. X’s music bled with passion and a yearning for redemption; on “Prayer,” we get a clear-eyed window into the concerns of his soul. There was a poetry to his music that transcended the demographic lines of the previous era’s gangsta rap boom. Here was music born from the streets but inspired by heart. DMX endures as a figure of resilience, making one line from “Prayer” particularly gut-wrenching: “So if it takes for me to suffer, for my brother to see the light/Give me pain till I die, but please, Lord, treat him right.” — JI

DMX, “Stop Being Greedy” (1998)

DMX floats over a menacing string loop on “Stop Being Greedy,” which functions as a blunt warning to anyone who disagrees with the rapper’s ideas about wealth redistribution. The chorus makes DMX sound like a hip-hop Robin Hood who steals from the rich to help the poor — “Y’all been eatin’ long enough, now stop being greedy/Just keep it real, partner, give to the needy” — while the verses are paranoid and violent, delivering in hoarse, shotgun-blast couplets. DMX makes it clear that he’s ready for a scrap, but mostly he just hopes to be left alone. “I don’t like drama, so I stay to myself,” he raps. “Keep focus with this rap shit and pray for the wealth.” — EL

DMX, “How’s It Goin’ Down” (1998)

The music video for “How’s It Goin’ Down” feels like a preview of director Hype Williams’ hood masterpiece Belly, beloved for its noir portrayal of life in the ghetto, its abundant love of hip-hop, and its visuals — Williams’ film style makes DMX’s skin look like it is glistening in technicolor. He stars in the film as Tommy “Buns,” a character who’s grimy like him, full of demons that a reverend couldn’t help him with. It’s a great performance by X. He could have done more with acting, just like Pac could have. “How’s It Goin’ Down” is a classic on its own merits, too: For someone whose rapping style was often so intimidating, DMX’s music could also be very seductive. He goes into a lower octave here, like he is reading a bedtime story for his lady, but X is still piercing and direct. The song’s plot is simple: X is making moves on a woman named Temika. This seems to already be causing some issues with her current man (“Heard he smacked you ’cause you said my name when y’all were sexin’/Ran up on some dude he thought was me, and started flexin’”). X isn’t all about sex — he wants to take care of you, too. But after some more flirting, he gives up. Temika has two children and is in an entanglement with the father of those kids. X doesn’t have time for that. Back to growling. — JB

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The Lox featuring DMX and Lil Kim, “Money, Power & Respect” (1998)

Opinion remains divided on whether the Lox’s debut album was a failed marriage of Yonkers hardcore and Diddy’s Bad Boy “jiggy” ethos, or a memorable setup for one of the most popular East Coast groups of the day. But there’s no debate that the title track is an incredible banger, with standout performances from Lil Kim on the hook and 16-bar phenomenon Jadakiss. Then there was DMX — himself on the verge of taking over the music industry with his debut LP — who delivered a sharp flurry of words to close out the track. “This ain’t no fuckin’ game!/You think I’m playin’?/‘Til you laying somewhere in a junkyard decaying?” he barks. With the gold-selling “Money, Power & Respect” cracking the top 20 as the Lox’s most successful single to date, it’s no wonder the group eventually left Bad Boy and joined DMX’s Ruff Ryders label. — MR

DMX, “Slippin’” (1998)

DMX was known for the battering force of his delivery, but he showed uncommon tenderness on “Slippin’,” crooning the gravelly, affecting chorus to this hip-hop ballad about overcoming trauma. The DJ Shok-produced beat teases a somber riff from the jazz-funk star Grover Washington Jr., and DMX uses this backdrop to chronicle a life “possessed by the darker side.” “Wanna make records, but I’m fuckin’ up,” he raps. “I’m slippin,’ I’m fallin,’ I can’t get up.” The single’s video ratchets up the tension, as an ambulance rushes DMX to the hospital. “Slippin’” didn’t do that well on the charts in the 1990s; the music industry tended to prefer adrenaline-fueled DMX records like “What’s My Name” and “Party Up.” But “Slippin’” resonated with many fans, and it has earned a loyal following over time — the track was certified Gold in 2017, almost two decades after it first came out. — EL

Jay-Z featuring DMX, “Money, Cash, Hoes” (1998)

How big was DMX in 1998? So big that by the year’s end, a few months after he reshaped New York rap with his debut LP, X popped up on Jay-Z’s Vol. 2…Hard Knock Life to lend some guttural gravitas to another ascendant Def Jam star’s bid for multi-platinum success. “Money, Cash, Hoes” exists mostly as a platform for DMX’s ad-libs — the deep growl that opens the intro, the titanic “WHAT!” and “UH!” and “COME ON!” that punctuate each chorus. (“All the ‘What!’ ad-libs that you hear in the beat were from X live,” Swizz Beatz recalled in a 2011 interview. “I wasn’t sampling the ‘Whats’ until way, way later. That’s just what X would always do.”) Jay gets in some slick verses of his own, but it’s DMX’s bark that echoes loudest all these years later. — SVL

DMX, “It’s All Good” (1998)

In “It’s All Good,” DMX rhymes over one of disco’s most indelible basslines, from the 1981 Taana Gardner classic “Heartbeat,” making a crossover between thugged-out hardcore and vintage roller-boogie disco, at a time when that was a rare move. He boasts about groupie love with his own over-the-top humor: “I like ‘em greedy/Black like Idi/Eyes beady and willing to give to the needy.” — RS

DMX featuring the Lox and Jay-Z, “Blackout” (1998)

The relationship between Roc-A-Fella and Ruff Ryders continued to pay off as the Nineties came to an end, with a joint tour and more collaborations. Jay-Z rode his natural born hustler’s swagger to the top, using his trademark flow mixed with the double-time that he originally came up on. X’s lyrical persona was something different completely: If Jay went to the dealership after dipping in his stash and spent $10,000 that night at the club, X was robbing dudes blind on his block. The phrase “wrong place at the wrong time” transpired when you ran into X. “Blackout,” from X’s second LP, is the best song they made together. Swizz Beatz’s trademark symmetrical beats mix with you-better-fear-us grittiness from the lead rappers. X’s raps have pauses between them, like he is waiting for his pitbull to bark with him. He and Jay caught lighter fluid when they made music together, but their partnership quickly fizzled out in the subsequent years. They’d always been more like frenemies, even when they first battled in the Bronx years before the fame. (Rumor has it that the battle was heated and it ended in a draw.) As Jay’s success grew to new heights and X’s problems with the law and addictions began to mount, their paths diverged further. Seeing signs of tension between them was sad, a reminder that all rap dynasties eventually end. Which is unfortunate: Both X and Jay brought life back to a region that needed it. “Blackout” isn’t just a call to arms for Brooklyn and Yonkers. It’s two of the greatest East Coast rappers, planting their flag in the game. — JB

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

DMX, “What’s My Name” (1999)

Irv Gotti helped craft this bulldozing single, which isolates and weaponizes a dissonant cluster of piano notes. DMX always had a gift for concise, easily shoutable hooks, but few songs in his catalog matched the simplicity of this 1999 single: “What’s my name?” the rapper yells. “DMX!” This is aural blitzkrieg, a series of threats (“Make cowards disappear into thin air”) and commands (“Stop talkin’ shit!”) delivered one after another with thunderous, unflagging intensity for nearly four straight minutes. “I’m not a nice person,” DMX warns. “I mean, I’d smack the shit out you twice, dog, and that’s before I start cursin’.” – EL

DMX, “Party Up (Up in Here)” (1999)

DMX and Swizz Beatz had a fruitful creative partnership that peaked commercially with “Party Up,” an absurdly boisterous hit from the quintuple-platinum album … And Then There Was X. This one opens like an air raid, with pile-driving synthesizers and shrieking whistles, and DMX rains insults down on “wack,” “broke,” “twisted,” “weak,” “whining” enemies. The chanting, whooping outro — “one, two, meet me outside, meet me outside” — also helped Swizz Beatz pad his bank account. That “part was spur of the moment, but it got famous and people started paying me extra to do the outro [to their songs],” the producer said in 2011. “I would charge $15,000 extra just for the outro.” — EL

DMX featuring Sisqo, “What These Bitches Want” (1999)

The beat, produced by Nokio of Dru Hill, comes in like the bell at Riverside Church in New York, about a 10-minute walk from where DMX used to battle in Harlem. X opens with a question: “What these bitches want from a nigga?” It wasn’t just X’s voice that was intimidating, his whole presence was. The tragedies and trials of his childhood made him into a lean machine, ready to spit so hard that his veins might pop. DMX, more than anyone else, was rap’s Mike Tyson — an example of the system, and the kinds of personal demons that made both men the deadliest alive. X yells before the rap starts, a rage that was meant for being locked in a cage. He says he doesn’t understand what women want from him, in part because he has so many different women that remembering them is close to impossible: Marina, Selena, Katrina, Sabrina, and about three Kims. He swears they are all treated fairly. Sisqo yells at the end: “YEEEEEEAAAAAAAAHHH.” It’s a three-minute moment of memory and pure id. — JB

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

DMX, “We Right Here” (2001)

By 2001, tales of DMX’s increasingly public and unstable lifestyle were circulating in the press. The first single from his fourth solo LP, The Great Depression, found him reasserting his perch as one of rap’s biggest stars. “Bring it! WHAT!/We right here/We’re not going anywhere,” he growls over producer Black Key’s assembly of percussion, bass, and minimalist keyboards. His growling lyrics push back against the perception that he’s about to fall off: “And y’all gon’ see/That the hottest nigga out there was, is, and will be me/Just like that/I can go away for a minute, do some other shit, and bounce right back.” DMX’s performance is purposely muted and determined, which may be why “We Right Here” wasn’t a major hit with an audience used to wild, over-the-top club ragers like “Party Up.” — MR

DMX, “X Gon Give It To Ya” (2003)

A hit in 2003, “X Gon Give It To Ya” has had a second life in the years since, thanks to TV and movie spots (notably Marvel’s Deadpool franchise) as well as baseball stars Xavier Nady and Xander Bogaerts, who have used it as walk-up music. The song’s popularity is fitting, given it’s one of DMX’s most pop-wise songs, distilling everything about his hyper-aggressive minimalism into three-and-half-minutes of hooks, taunts, and threats that don’t sound idle. When he barks, “This rap shit is mine, motherfucker/It’s not a fucking game,” you believe him on both counts. — CH