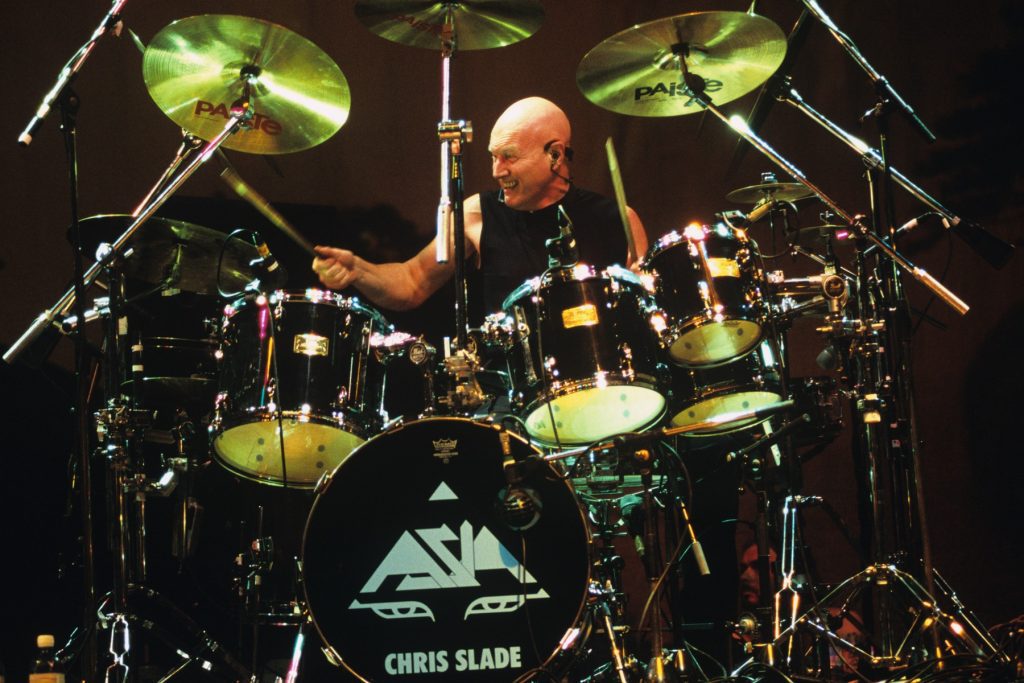

Drummer Chris Slade on His Years With AC/DC, the Firm, David Gilmour, and Manfred Mann

On the surface, AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck,” Manfred Mann’s Earth Band’s “Blinded by the Light,” and Tom Jones’ “Valerie” have nothing in common. They were recorded in different decades, targeted at different demographics, and they don’t sound even remotely alike. But they all feature the drumming of Chris Slade, a journeyman Welsh musician who has also played with Olivia Newton-John, Tom Paxton, Uriah Heep, David Gilmour, the Firm, Gary Moore, and Asia.

He’s best known for joining AC/DC in 1989, just in time to play on their comeback LP, The Razor’s Edge. He left the group in 1994 when they reconnected with classic-era drummer Phil Rudd, but rejoined in 2015 when legal problems forced Rudd to take an extended leave of absence. Slade traveled the world with AC/DC throughout the Rock or Bust tour of 2015 and 2016, even after vocalist Brian Johnson departed near the end and was replaced by Axl Rose.

The current status of AC/DC is such a mystery that even Slade doesn’t know if he’s still their drummer. But he still phoned up IndieLand to tell amazing stories from his long career, going all the way back to his teenage days in Wales, where he connected with a local singer calling himself Tommy Scott, years before he cut “It’s Not Unusual” and became known to the world as Tom Jones.

How’s your quarantine going?

Pretty good. I’m in lockdown, as usual, as I presume you are in the States. I can’t really go anywhere. We’re allowed into the pubs now, but I’m not going. Things are pretty nasty.

I want to talk about some key moments in your life. Tell me what first drew you to the drums as a child.

I think it was probably my brother Danny. He was a drummer in a street marching band. He used to bring the drum home to clean when I was about 10. Of course, he didn’t clean it. I did. Being seven, eight years younger than him, I got the job. For that, he taught me a few licks.

Who were your drumming heroes as a teenager?

Definitely Buddy Rich, without a shadow of a doubt, as many drummers of my generation would also say.

What inspired you about his playing?

He had a very crisp sound and, of course, amazing technique. Gene Krupa was great and a great showman, but in my opinion — people might disagree — Buddy was much crisper.

How old were you the first time that you were paid money for playing drums?

1983, I think. [Big laugh] I actually think I was probably 11 or 12, probably with a friend of my father. My father was a tap dancer and singer. That’s where the rhythm probably comes from. Also, I was born on the side of a railway station, so I blame that as well.

How did you first meet Tom Jones?

I knew of him because he worked sometimes with my father’s concert party. That’s what they used to call them, concert parties. They went around the workingman’s clubs in South Wales, where I was born. I hadn’t met Tom at that point, but he went to school with my brother. He’s seven or eight years older than me.

I had left school at the time and was working a summer job in a shoe shop in Cardiff, which is the capital city of Wales, 12 miles from where I was born, in Pontypridd. I’d heard that Tom’s band had either lost or sacked their drummer the night before. I knew what the guys looked like in the band because they were famous around the towns and villages.

One day, in walks the lead guitarist of Tom’s band. They were called Tommy Scott and the Senators. And so I walked up to him. He was in his twenties and I was 16. I’m quaking in my boots, but I say, “I heard you need a drummer. I’m a drummer and I live pretty close to Tom,” which I did, about half a mile.

We arranged for them to come to my house, where I had my brand new Premier kit. The whole band came, including Tom. I think Vernon [Hopkins] the bass player said, “Can you play the start to ‘Walk, Don’t Run’ by the Ventures? I hammered it out, which was quite difficult in those days, especially for a 16-year-old. But I knew it properly, and my kit looked amazing because it was a brand new kit out of the showroom, out of the boxes. They went, “Alright, let’s go to a pub and rehearse.”

Everybody grabbed a drum and we got on the local bus, which was a half a mile walk. Then we changed. That’s the way things were done in those days. We ended up going to this pub and we rehearsed, and I got the job. I was with Tom for seven years in total. Tommy Scott and the Senators became Tom Jones and the Squires. The rest is history for Tom.

Tell me about recording “It’s Not Unusual.” I know you didn’t wind up on the master recording that came out.

As far as we know, I didn’t play on the definitive version. But they tried everything. I played the demo and they tried everything. They tried it six times, maybe even more. And they used almost every top session player in Britain. To my knowledge, it was a drummer called Andy White, the guy that replaced Ringo Starr in the Beatles on their first record, “Love Me Do.”

That famously pissed Ringo off.

[Sarcastic laugh] Of course, it didn’t piss me off at all …

Wikipedia says that Elton John plays on it, but that can’t be correct, right?

It’s not. It wasn’t on that. That was with the Squires. We were recording on Denmark Street in London when it was all music stores and recording studios and publishing companies. Now it’s Indian restaurants. Denmark Street, of course, is the famous Tin Pan Alley. We were doing a demo just for the Squires. Our keyboard player, for some reason, didn’t turn up. I ran across the road to a coffee shop called the Gioconda, which is where everyone used to hang out.

I opened the door and went, “Any keyboard players here?” And this young, skinny guy gets up, probably the same age as me. He came across the road and he played on a Squires session for 10 pounds. That was the going rate.

Do you know what song it was?

No. It disappeared. It never came out, it never went anywhere. That’s when the Squires were Tom’s backing group. “Thanks a lot. Really good.” “What are you doing?” “I’m a songwriter. I’ve just signed with a publishing company upstairs.” “Great, what’s your name?” “Reg.” “OK.” Of course, a few months later Reg changed his name to Elton John.

Why did you leave Tom’s band?

In early 1970, I found out that the rest of the touring musicians were getting about triple what I was being paid. [Laughs] Drummers, man …

Flash forward and tell me how you wound up in Manfred Mann’s Earth Band.

Right after I left Tom, I got this call from Manfred Mann. He said, “A couple of people recommended me to you because I’m putting a new band together.” But I had done some sessions with Manfred when he had a big jazz band called Chapter Three. I think they made two or three albums. I played on whatever the last one was. He knew I could play and he obviously liked what he heard, and he asked me to form a band with him.

He said, “Do you know any bass players?” I said, “Funny enough, just last week I met a bass player called Colin Pattenden.” Manfred also knew [guitarist] Mick Rogers from Australia. We put that band together and it became Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. It was called Manfred Mann in the beginning, but we couldn’t get any work because everybody thought of the pop band, which was not very popular at that time. So we became a so-called “underground band,” which is what it was called in those days — a little bit like Cream or something, that type of band.

Tell me what you remember about making “Blinded by the Light.” It’s such a unique take on a Springsteen song.

That’s Manfred, actually. He is the one famous for arranging the songs of other singer-songwriters. He’s famous for doing Dylan songs, for instance. Manfred and I were given a Springsteen album that disappeared without a trace the first time it came out called Greetings From Asbury Park. I absolutely thought it was amazing. I thought this guy was fantastic and, obviously, Manfred saw a lot of worth in him too.

Manfred did an arrangement and he played it for us. We went, “Um, I don’t really like that Manfred, sorry to say.” And then he went away and did another arrangement, and we all went, “That’s fantastic. We gotta do it.” It shows you what can happen sometimes.

Were you shocked to see it hit Number One in the States? To this day, Bruce himself has never even managed that.

Shocked beyond all.… I know a record company guy that said, “I knew it was a hit as soon as I heard it.” I said, “That’s funny, because we didn’t.” We didn’t have a clue. It was a complete shock.

Settle a long-standing rock debate. Is he singing “deuce” or “douche?”

[Laughs] It is a long-standing debate. There’s an even longer story to it, which I won’t go into. I’ll save it for the book. But the recording machine was set up wrongly. Everything was very sibilant and we didn’t know the lyrics. That’s one thing. There were no lyrics on the album Greetings From Asbury Park. There was no way in those days, no internet, to find out lyrics. The whole band sat around for hours trying to work out the lyrics. That’s how we used to do it in those days. There was nobody saying, “Why don’t you phone Springsteen’s management?” How do you do that? You don’t even know who they are or how to get in touch with them. They’d probably be like, “We’ll get back to you next week.”

We’ve never heard of a “soul fairy band” [in our cover of “Spirit in the Night”]. That wasn’t a thing that was in Britain. It came out as “song fairy band.” To answer your question, the actual lyrics are “revved up like a deuce” like a deuce coupe [car.] Those are the actual lyrics that Springsteen actually wrote. But because the machine head was set up wrong, it came out very sibilant and very similar to what you and the whole of America heard as “douche.” That’s probably what took it to Number One.

Flashing forward again, what’s your favorite memory of your time on the David Gilmour tour in 1984?

Oh, they’re all great memories. I loved that. Dave is such a great guy. A genuine guy. He treated the band absolutely fantastic. He’s genuinely a great guy. He’s intelligent and an amazing player. One of the nicest people you could ever meet. So at the end of the tour, he took the whole band and their families on holiday to the Bahamas.

How did you wind up in the Firm?

To back up a bit, I got this call from Dave Gilmour. It was like, “Hello, Chris, Dave Gilmour here.” I looked at the phone to see if I was hearing correctly. “I’m putting a band together. I’d like you to play drums.” I said, “Dave, that is absolutely fantastic. But I’m working with Mick Ralphs’ band.” They were friends, [he and] Mick Ralphs from Bad Company. He said, “That’s all right. Mick is doing it too.” I thought, “Oh, fantastic.” And I said, “OK, Dave. We’ll sort it all out and I’ll see you soon.” He said we were going to start in about a month or so.

I said to my wife, “OK, we’re going down to the pub to celebrate.” We went down to the pub and had some lunch and some beers. We came back and the phone rings. I pick up and hear, “Hello, it’s Jimmy Page here.” I’m going, “Come on, friend. I know it’s you. Stop messing about.” “No, no, no, no. It really is Jimmy Page.” “How are you, Jim?” We’d never met, but we had mutual friends. “Me and Paul Rodgers are putting a band together and we’d really like you to play drums.” I was like, “Oh! Jim, you won’t believe this. An hour and a half ago” — I was thinking honesty was the best policy — “an hour and a half ago, David Gilmour asked me to do a tour and it’s starting in month or so.”

I was thinking, “Oh, God, that’s the end of it now.” And he goes, “That’s all 0right. We’ll wait.” Holds phone away from face. Stares at phone for about 30 seconds. Couldn’t believe it. “OK, we’re not in any sort of rush, really. How long is the tour?” I said, “I think it’s going to be three months.” “Well, keep me in touch and we’ll see what happens when it finishes. But we definitely want you to play drums.” I went, “OK, thanks a lot. Thank Paul and I’ll call you and keep you informed with what’s going on.” We definitely went to the pub after that. Again.

That’s a big day.

I have it written down somewhere, the only time I’ve ever done that. I wrote the date in red.

Tell me about the decision to tour with the Firm and not play any songs by Free, Bad Company, or Led Zeppelin. I’m sure the audiences were dying to hear that stuff.

Absolutely. And I wish we had. I really wish we had. It flowed like a really great band. Why wouldn’t it? One of the greatest singers ever. Certainly blues singers. And one of the greatest guitarists. And Tony Franklin on bass, of course. As he said himself, he’s a monster. A fretless monster. It was great. I had a great time.

But as you can imagine, Tony and I had nothing to do with the input for the band. It was Paul and Jim. To me, it was suicidal not to do Bad Company or Free or anything like that, or Zeppelin. To me, that was just not the thing to do. I come from the showbiz side of things. As I say, my father was a tap dancer. You do everything you can to entertain the public.

I imagine they wanted to break out of the past, not get stuck there, and just focus on the present.

I think that’s the thing. “We don’t want to get known as doing our old stuff. We want to do the new stuff.” I think what you just said is true.

Do you think the group lived up to its potential?

I can’t judge that. Only the audience can tell that. I still get people coming up with Firm albums saying, “It’s my favorite band ever.” That is genuine. When I’m on the road, it’ll happen twice a night. After all that time, we must have done something right.

How did you hear about the job opening in AC/DC?

I was working with Gary Moore all the way through 1988-89, about a year. They had the same manager, AC/DC and Gary Moore. His name was Stewart Young, no relation to the Young brothers. I think he put me forward. I think, actually, Malcolm came to a Gary Moore show in Birmingham [England]. He saw me play that night. A few months later, after Gary Moore had finished, I got a call from Stewart Young saying I had a chance at an audition. What I didn’t know, I found out later, was that they had already auditioned 100 of the top players. People in bands would say, “Don’t tell my band, but I really want to try out with you guys.”

I was told this by Dick Jones, the drum tech. He auditioned even people that weren’t professionals. He spent weeks auditioning people, like “OK, next …” This was without the band. He had been with them for 30 years by that time. He sorted the wheat from the chaff, and the professional players got proper auditions with the band playing with Angus, Mal, and Brian singing. We did things like “Back in Black.”

It was an hour from my home, actually. It was just north of Brighton in England. I probably played about 10 songs, though I can’t remember. I only remember that we played “Back in Black” and all the standards. I thought I had done really badly. At the end of it, I was like, “OK, see you. Thanks a lot.” I was so preoccupied at kicking my own butt since I’d done so badly that I got lost, an hour from my house. I phoned my wife and said, “Look, I’ve done the audition and I’m headed back now.” “How’d you do? How’d you do?” “Really badly. Terrible. I’ll tell you about it when I get back.”

I get back to my house eventually, of course. She walks up the path and says, “So you did really badly?” I said, “Yeah, I shouldn’t have done that, shouldn’t have said that, shouldn’t have played that.” She said, “They just called and said to tell you that you got the gig.” They called before I’d even gotten home. I was number 100. Dick told me that and the guys confirmed afterwards. There were really top players, but I won’t mention any names.

Tell me about recording “Thunderstruck.” That song became a key part of their comeback during that time.

Angus and Malcolm had already written it, of course, as they write everything. They demoed it, like they always do. Angus or Malcolm were playing drums, real drums. I’ve heard a few demos where they use a drum machine as well. But it’s them hitting the buttons.

And so it was one of the demos I got to this album that had no title. I was told to learn those, and then we went into the studio. I think it was [Mike] Fraser, the engineer, that said, “Can you double your fills on that?” I said, “Sure I can do that. No problem.” They just seemed incredibly surprised I could actually play the same thing twice. That’s the way it seemed to me. I did double the fills and made the thing much bigger. They said, “When that ‘thunder’ bit comes in, can you just dub a big tom on that with the ‘thunder?’” I said, “Sure.” They seemed surprised at that too. As a lot of drummers know, it ain’t that difficult.

Do you recall much about making the video? It’s become super-iconic and you’re pretty prominent in it.

I can’t remember sets and things like that. But David Mallet was the video guy and he set two cameras on the drums, which I thought, “Wow, what is going on here? Attention paid to the drummer!” It turns out he loves drums. He cut it in such a way that the drums are featured a hell of a lot, I’m very, very pleased to say.

How was the tour? Those must have been some of the biggest crowds you’d ever played to. They were a stadium act at that point.

To be honest, it wasn’t that much of a stretch for me. I played a week at Madison Square Garden with Tom Jones. I’ve done festivals, been to festivals both as a punter and an artist. It’s something I’ve done all my life since I was a teenager. To me, it’s another day at the office.

What happened around the time of Ballbreaker?

I did the demos for Ballbreaker. That’s when the split came about, when Phil came back in.

How did you find out?

I got a call. I’d been doing demos for Ballbreaker with Angus and Mal in London. They had a small demo studio. This went on for months, these demo sessions. I even ended up staying up in London because driving back and forth all the time was a real pain. To cut a long story short, I got this call from Malcolm. He was incredibly nice. I remember him saying, “This is not anything you have done or anything that you haven’t done, but we’re going to try Phil out again.” I went, “Oh, wow. That’s a biggie. So I’m gone then.”

He said, “No, no. We don’t want you to leave. We want to keep you on. We want to keep paying you. We don’t even know if Phil can play drums anymore.” And I said, “Malcolm, I appreciate your phone call very, very much. But if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” He said, “No, no. We want to keep you around.” I said, “No, I can’t do that. It’s not in my makeup.” We talked for a while, actually. But that was the outcome. That was the end of it.

I actually did leave. No doubt, Phil would have come back in anyway, but it would have perhaps delayed the inevitable.

How was your experience playing with Asia in the early 2000s?

It was really good. They didn’t know where I was, phone number or anything, so they wrote a letter to my last address. I got this letter through my letterbox that said, “We’d really like to see you because we’d like you to play drums with Asia.” I went, “Oh, wow. That’s pretty cool.” I went down to Wales where their recording studio was. They turned out to be nice guys. A few weeks after, we had been recording in their studio and this guitarist shows up who had been recommended by a producer, Guthrie Govan. It was like, “Jesus Christ, this guy is amazing.” He still is. He travels with all sorts of people, absolute tremendous player. That was great. I was in and out of Asia with Guthrie for about seven years total.

When you heard about Phil Rudd’s troubles, did you think maybe the band was going to call you back in?

To be honest, no. [Laughs] I didn’t. I had hopes, of course; why wouldn’t I? But time went on and on. Friends and fans and people kept saying, “Have they called you yet? Have they called you yet?” I went, “Look, they’re not going to call me.” “No, they’re bound to.” “No, they’re not going to call me.”

Eventually, I was on the road with [the Chris Slade] Timeline in Switzerland and I got the call from management. They said, “We’d really like you to rejoin the band.” This went on for a while. At the end of it I said, “OK, we’ll get together and I’ll see you in the States.” Then I said, “Can I ask you? Did this come from the band?” And he said, “Of course, it came from the band! I’m not going to call and offer you a job if the band don’t know about it.” Even at the end of the conversation, I was still apprehensive about it. But he confirmed that Angus and the guys were all on for this. That made me feel a hell of a lot better.

How did it feel to get back behind the drum kit at that first rehearsal?

Oh, it was brilliant. Absolutely brilliant. We always got on as people, so it wasn’t that different. Everybody got a bit older, including myself, but it felt great.

Did you appreciate the experience more the second time around?

I’ve always appreciated it. [Laughs] I’ve always appreciated working. And more importantly, playing drums. I always appreciated it.

What happened on the tour that led to Brian’s departure?

Brian was getting unhappy. He kept saying, “I’m feeling bad. I’m feeling bad for the fans.” I wear in-ear monitors. First time I ever used them. I could hear everything perfectly, including Brian. I kept going, “Brian, it’s really not as bad as you think it is. I know you have professional pride. But you keep saying you screwed up. It’s really not as bad as you think.”

I don’t know the end of the story. The band, including Brian, was in Miami. Tim [Brockman], the tour manager said, “We’re going to be staying here for a while.” I went, “Oh, really? I thought we were going to a new city next week.” He said, “No, we’re going to be here for a few weeks.” I said, “Why?” He said, “I’ll tell you later.”

I never got the story. But I had been talking to the crew and they filled me in. All I know is — and this is serious; I don’t know the details — all I know is that Brian went from Miami to home. He lives in Florida anyway. As far as I know, he stayed there.

There were more shows to do on the tour, though. What discussions did you guys have about how to solve that problem?

To be honest, that is Angus and management. That’s above my pay grade [laughs].

Besides Axl Rose, did you hear about any other possible replacement singers?

We were in Atlanta, Georgia, and we auditioned a few people. Some of them were really good. I said, “What’s happening tomorrow?” Someone goes, “Tomorrow we’ve got Axl Rose.” I went, “What?! Axl Rose!” I knew his reputation. “Wow, that is left field. I never saw that coming.” I’d only ever heard his Guns N’ Roses voice. I didn’t know he could cut it. He showed up the next day at the rehearsal place in Atlanta and he seemed like a really nice guy. He was telling jokes. The rest of us were like, “Wow. This is unprecedented.” At least in my mind, that is. When he started singing, it was like, “Wow!” I never even knew he could sing like that. It was brilliant, absolutely brilliant. He turned out to be the nice guy that I thought he was. I found out he wasn’t putting on an act or anything. That’s how he was.

The guys you auditioned before Axl, were these known singers or relatively unknown singers?

Relatively unknown, I would say. Some tribute-band guys and some of those guys are really good, as we all know. And, of course, I had no input whatsoever. Nobody says, especially to the drummer, “What do you think?” [Laughs]

It must have been weird during the Axl shows to look out and not see Brian, or even Malcolm, for that matter. Two key parts of the band were no longer there.

Yeah. We had auditioned for a few weeks with Axl. I’m pretty spontaneous in my life and sometimes drumming, as well. To me, it was like, “It sounds great. Let’s go with it. Come on, Slade, do your gig. It’s what you’re getting paid for.”

At the end of the tour, did Cliff Williams say that he was retiring from the band?

I think that was during the tour. I think I got it, actually, from Tim, the tour manager. I think he just actually said one night, probably at the bar, “Cliff is packing in after this.” Cliff confirmed it probably over the last week or so of touring. He said, “No, I’m done.” We talked a few times, Cliff and I, in various bars in various hotels. I remember meeting Cliff when he was in a band called Home, a British band. I was in Manfred Mann’s Earth Band and we played the same gig. We were both on the bill. I knew him from way back in the Seventies. He didn’t want to go on the road anymore. He wanted to go fishing with his son, who’s a professional fisherman. It was like that.

The tour ended in Philadelphia. Did you think that night, “This could be the last-ever AC/DC show?”

I never thought that, actually. Never thought that because whatever happens, Angus will want to continue. He’s 65 and he’s still got all the energy that he needs. He still plays the same. Why wouldn’t he, no matter who is in the band? Stevie [Young] was in the band, completely different, but he did a great job covering, if that’s the right word, for Malcolm. By the way, Malcolm was a genius rhythm guitarist. Absolutely genius. Don’t forget, I’ve worked with a few.

There were rumors at the end of the tour that Angus was going to go into the studio with Axl to make a new AC/DC record. Did you hear anything about that?

No. Not to my knowledge. That is where my actual knowledge ends, actually, with the end of the Rock or Bust tour.

At the end of the tour, did you talk to Angus? Did he say anything about the future?

No. Absolutely no. [Laughs] And he never would, anyway. They used to take five years between albums. They still do, at least. No. There would be no discussion, not even between Angus, Cliff, and Brian. There would be no keeping in touch every week. There’s none of that. It’s like, “OK, that’s over now. We’ll talk again in five years.” And that is a fact.

Pictures have surfaced showing Brian, Cliff, Angus, and Phil near a recording studio in Vancouver. The fans all think they’ve made a new album. Do you know anything about that?

Nope. I don’t at all. To be honest, those pictures are so old. I think it was probably … I don’t know if I was the first drummer to go through Canada. But it looks, to me, like old pictures, to be honest. If you look at the hair on everybody and what the hair is like now, including me, you’ll see what I mean. There are so many rumors about AC/DC. There are daily, and I mean daily, rumors. “Oh, Angus has bought New Zealand.” It’s ridiculous. “Oh, I know things because I know. They recorded an album and they’re going to be touring in 2020!” You know what? They’re not [laughs].

I keep reading they are taking old Malcolm riffs and making new songs out of them with Brian singing. That’s the rumor at least.

That could happen. We all know about technology. I’m certain that Malcolm and Angus talked in great depth about this before he passed and before he was really, seriously ill. I’m sure there was a master plan. Of course, you throw away plans. Plan A turns into Plan Z. Personally, my gut feeling is that Angus is not going to retire. There could quite possibly be another album. I’m pretty certain there will be. Who is on it? I have no idea. Will Cliff come out of retirement? Who knows? If he’s had enough fishing for a while, maybe he’ll want to come back to rock & roll.

I’m looking at their Wikipedia page as we speak, and it lists you as their current drummer. Do you think that’s accurate?

To my absolute knowledge, and this is me being absolutely honest, I am the current drummer in AC/DC. [Laughs] It may sound deluded to some people. I’ve said that before in interviews and people have gone, “The man is deluded. He’s lost it. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” It actually says that? I’ve never looked.

I mean, it’s just Wikipedia. But that’s what it says.

Yeah, well, nobody has ever called me and said, “By the way, you’re not the current drummer,” or, “By the way, Phil’s been in the band for three years.” Nobody has ever said that. As far as I’m concerned …God, I’m philosophical enough to realize that Phil may well be back in the band. I have no idea. I had no idea last time when they called me before Rock or Bust. I’m open to all possibilities. That’s the way people should be, open-minded.

To move on here, tell me about the Chris Slade Timeline. It must be lots of fun to do concerts where you can finally play music from your entire career and not just one band at a time.

Oh, yeah, I love it. Half the set is AC/DC. And half is other material, stuff I’ve worked on, like the Firm, Manfred Mann’s Earth Band. We do “Blinded by the Light”; we even do Tom Jones. That sounds bizarre, but we have two singers. Bun [Davis] is the name of the singer that does AC/DC. Steve [Gee] does the other material, such as David Gilmour, the Firm.

We play for like two hours. I can only do this because the band is so good. They are world-standard. It’s James Cornford on guitar, Andy Crosby on bass, Michael Clark on keyboards and guitar. He plays rhythm guitar. I’ve known him as a keyboard player. I said, “We’ve got to get a rhythm player” and he goes, “Oh, I play guitar. And I cut my teeth on AC/DC. That’s the first things I’ve learned.” I had no idea when I put this band together that that was the case.

It’s a pretty amazing cross-section of songs, mixing “It’s Not Unusual” with “Thunderstruck.”

Yeah. We play for two hours, at least. Nobody is disappointed. Nobody. In fact, when I announce the last song it’s always like, “Oh, no!” Seriously. It could only work because the musicians in the band are so adaptable and so good.

Tell me about your future plans. Do you ever think about retirement, or are you going to drum until you drop?

Drum until I drop, most definitely. You won’t believe this, but I have a song that says something like that. We just recorded it. We’ve started doing original songs as well. I’m definitely not retiring. Only if I was ever forced, for whatever reason, to do it. I’m still playing with the same power that I’ve always played [with]. When that day comes where I can’t, I’ll stop. I’d be embarrassed if I couldn’t come up with the goods, as anybody would.

I know it’s a different kind of gig, but I saw Louie Bellson play on what I think was his 80th birthday. I thought, “Wow!” I know it’s a different style of drumming, but if I thought I couldn’t do what I wanted to do with AC/DC-type songs, I just wouldn’t want to continue. I will rock till I drop.