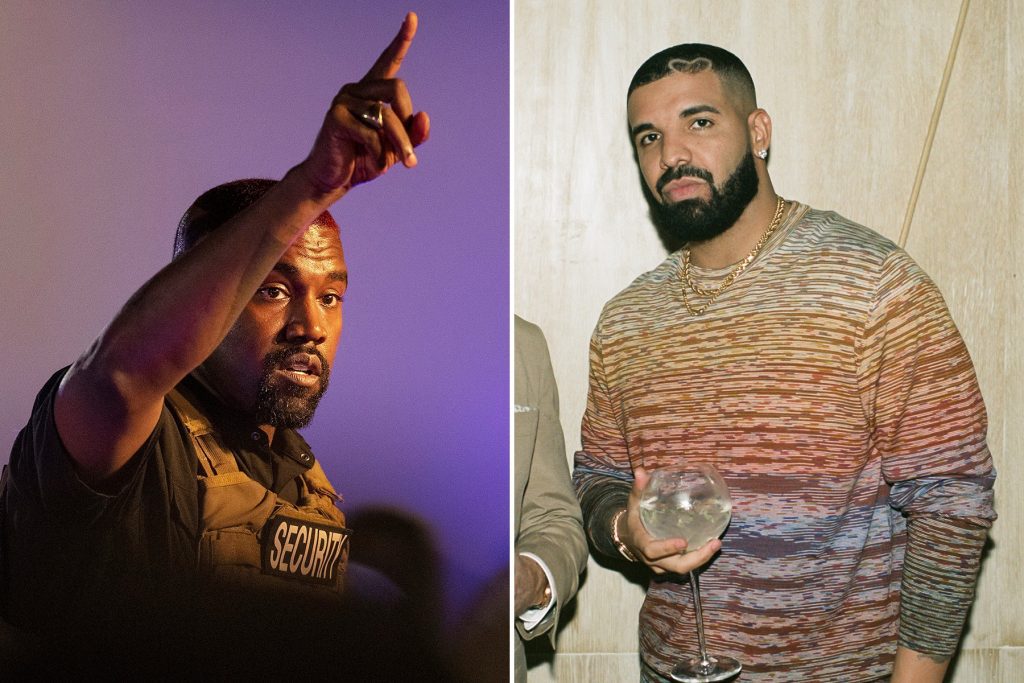

How a Beatles-Obsessed Producer Helped Drake Make His Latest Gloomy R&B Hit

Drake waits until the second half of Certified Lover Boy to deploy the gloomy R&B bomb that has been one of his most reliable weapons since Take Care. That album included “Marvins Room,” which found Drake drunk at a club plotting the pettiest of revenges — calling his ex and smearing her new boyfriend. The dynamic is reversed on Certified Lover Boy‘s “Race My Mind:” This time, the object of Drake’s interest is out “all night dancin’” and “coming home intoxicated” — if she comes home at all. Drake’s delivery is smooth but weary, glassy-eyed and edging past irritable; his dignity is dissipating rapidly. “I hit you like, ‘please come home to me,’” he sings. “You’re not understandin’, no/You gon’ make me beg, make me plead.”

“Race My Mind,” which has already amassed more than 17 million streams with just three days of data available, is co-produced by Scott Zhang, a 23 year-old singer, multi-instrumentalist and sampling obsessive who records as Monsune. His major placement comes despite his low profile — he has just six songs to his name, and he had never done a phone interview before speaking with IndieLand. Like most producers the morning after their name appears in the credits of a Drake album, he sounds pleasantly dazed by the whole experience. “I feel like [Drake] hasn’t really done a wounded R&B track for quite some time,” Monsune says. “I’m glad he brought that energy back.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Monsune grew up in the Toronto suburbs, where, like many kids, he developed a healthy obsession with the Beatles. But unlike most of his peers who admired the Fab Four, Monsune was driven to try to emulate their mixture of accessibility and technical wizardry while he was still in middle school. “Do you know that song ‘Because’ on the Abbey Road album?” he asks. “The first thing I ever recorded was me trying to do the vocal harmonies to that.”

His consumption of music was intense plus omnivorous — “I would just come home, listen to music, and practice guitar; for a long, long time, that was all I did,” he explains — and his enthusiasm for a wide range of talent, from the Brazilian great Gal Costa to the harpist Dorothy Ashby, Tame Impala to Prince, bleeds through the phone. “What partially fueled my obsession [with music] was the fact that my parents were immigrants who came to Canada from China in the 1980s,” Monsune continues. “They didn’t have a reference for Western music, and didn’t play it around the house, so I felt like I was a little behind. I thought I had to dig harder because I don’t have as much of a starting point to go from.”

He began piano lessons early, and added guitar, drums, and some trumpet to his repertoire before high school. But Monsune also became increasingly consumed by the art of sampling, which allowed him to play around with whatever sounds he liked, even the stuff he couldn’t play on an instrument. “I got into those people, J Dilla, Madlib, 9th Wonder, the ones who are really the greats when it comes to sampling,” he says. “I was very into this idea of taking samples and using them in a pop music context.”

In 2017, while attending college, Monsune decided to release one of his sample-heavy compositions for the first time. “It was just a young person’s desire to share something they’re proud of,” he says. “There wasn’t any real expectation.” Monsune is self-effacing; he calls the video for “Nothing in Return,” made on the cheap with friends at a local park, “such high-school type shit.”

But only the most curmudgeonly listeners could apply that description to the song, which starts with an arresting sample that lands somewhere between the harpsichord sound from early Ne-Yo hits and wind-chimes quivering under pressure from intense winds. The beat is a funky lope, and Monsune’s singing is convincingly anguished: “If you kept me waiting on your word/Would you give me nothing in return?” Horns add a vivid flourish in the middle of the track, adding more rich texture; this could be a sample, but it’s Monsune’s playing — “I’m not very good,” at the trumpet, he says modestly, “but I can still play simple shit” — which helps bring the track to a peppy end despite its depressing final line. “I guess your silence keeps me warm,” he sings.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The warm response to “Nothing In Return” convinced Monsune it might be worth trying to pursue a musical career. “Let me run with this, see how far it can go,” he remembers thinking. He moved back into his parents’ house to reduce his cost of living and focused on producing more music. He put nothing out for nearly two years. “It took a really long time,” he says. “I tend to take a long time.”

Monsune’s next batch of tracks built on the funky promise of “Nothing in Return.” This was especially true for “Cloud,” which positions the singer as a one-man neo-soul outfit, and “Outta My Mind,” which has some of the lush beauty and handsome harmonies of late Seventies yacht rock. The track’s video shatters the reverie with a restaurant brawl; in the song, Monsune also unleashes an unbridled scream of the type rarely heard in modern R&B — or any other genre — which he sees as a tribute to Prince’s “International Lover.”

“Listening back, did I really do that?” the singer says. “It was really adolescent experimentation stuff. I’m like, ‘I actually did that. That’s so indulgent.’” But listeners don’t seem to mind, as “Outta My Mind” has amassed more than 28 million streams on Spotify alone.

Around the time Monsune released Tradition, his debut EP, he also received an invite to a Red Bull Music Academy event in Calgary where he connected with a number of producers, including Nile Goveia, who subsequently became a friend. “He’s one of those best kept secret guys,” Monsune says. “The first time we linked up, we made three beats,” including what would eventually become “Race My Mind.” Goveia “was talking to some people in OVO at the time” and sent over some instrumentals, which is more or less how modern big-budget albums come together. (Goveia also co-produced the Drake, Nicki Minaj, and Lil Wayne track “Seeing Green” from May.)

While waiting and wondering on the fate of “Race My Mind,” Monsune has quietly started building his resume as a beat-maker for others, collaborating with his friend Jonah Yano and co-producing Foushee’s “My Slime” single. “Working on something on my own, putting my own voice on it, sharing it with the world, that’s kind of stressful,” Monsune says. “I feel like working on other people’s music is less of a personal headache.”

Following the credit on “Race My Mind,” it’s likely Monsune will have ample opportunities to work with other artists, should he choose to. He’s in no hurry. “For the next couple weeks I’m gonna ride this high,” he says, “and eat a lot of good food.”