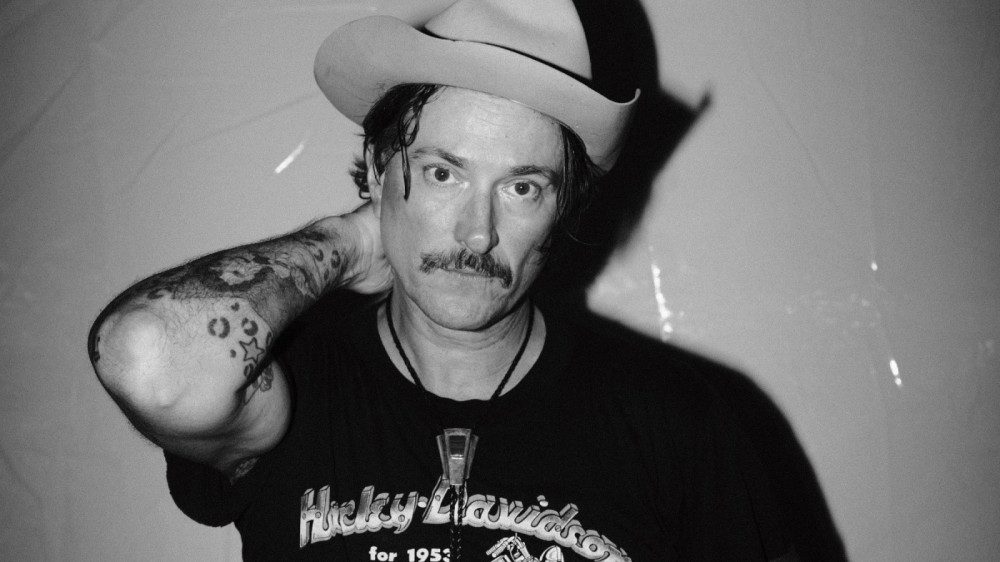

How Butch Walker Cracked the Live-Performance Code With Fist Pumps, High Kicks, and a Piano-Rocking New Album

It’s a hot late-summer Saturday at the Pilgrimage Music & Cultural Festival outside Nashville, and Butch Walker has just jumped off the stage of the Americana Music Triangle tent and is wading into the crowd. About half the audience has never seen Walker perform before — he took an impromptu poll — and they look mesmerized by the lost art of showmanship he practices: the pick tosses, the high kicks, the fist pumps, and the journey into the people. Walker hops up on a rickety bench and enlists a fan to hold his mic while he continues to sing and bash away at his guitar. By the finale, a furious rendition of his 2006 T. Rex-style glam-rocker “Hot Girls in Good Moods,” he has the entire tent crouching in the grass, waiting for his signal to rise up and dance deliriously to the chorus.

After the soul-crushing darkness and isolation of a pandemic that, depending on who you ask, is kinda sorta over, Walker’s hourlong festival set is distilled euphoria, a long-in-the-making release for both artist and fans. It’s also a table-setter for Walker’s new tour, his first in four years, on which, I suggest, he’ll demonstrate how he’s cracked the code of the live performance.

“I don’t think I did?” Walker says, laughing off the compliment during an interview at his home studio in the hills of rural Tennessee. The Cartersville, Georgia, native and hot-shot producer for albums by Green Day and the Wallflowers — and a track on Red (Taylor’s Version) — is doing his best to appear humble. But even he seems to know that’s a silly task, after commanding a tent full of people just a week earlier to dance, shamelessly and badly, and have them actually do it.

“The beauty of playing a festival is that 80 percent of the people there don’t know who you are,” he says. “I consider myself a low to mid-level artist. I’m not a household name. It’s a fun rush to see the faces. They are taking this in, they’re enjoying it, now let’s seal the deal. That sounds cheesy, but to me, it’s so fun to win over people. Plus, I’ve never been stimulated by staring at my feet.”

Walker’s studio near Thompson’s Station, Tennessee, is a converted barn, painted black, with a stained-glass cathedral window, and a sign reading “The Butcher Shop” over the door. It’s stocked with too many guitars to count, a drum kit, and a Yamaha C3 Baby Grand that he says he purchased about 15 years ago with “my first-ever fuck-you money from music.” That particular piano plays a major role in Walker’s new album, Butch Walker as…Glenn, a freewheeling concept record about a bar-room musician that calls to mind the best of Seventies piano-rock. Think Elton, Zevon, and Billy Joel. Glenn is Walker’s middle name, and he conceived the character while producing an upcoming album by the singer-songwriter Morgan Kibby, on which she too inhabits a character. Hers goes by the name Sue Clayton, and she duets with “Glenn” on the standout track “State-Line Fireworks.”

“Sue Clayton is a washed-up, tragic widow, who maybe was an actress back in the day, and now lives in the Palm Springs desert doing phone sex as a side hustle,” Walker says. “We do a skit on her record where you hear a recording of her phone-sex greetings, and it’s me as a caller named Glenn. Morgan said, ‘Why don’t you make Glenn the character for your record?’”

After releasing nine albums under his own name, beginning with 2002’s Left of Self-Centered and, most recently, 2020’s polarizing American Love Story, Walker jumped at the opportunity to step outside of himself. Especially in the wake of the shitstorm he endured following American Love Story, an intricately crafted rock opera about a politically and culturally divided country. Just like on Glenn, Walker played characters on that LP too — he sang some songs from the POV of an earnest liberal, others from a MAGA believer — but some of his fans couldn’t make the distinction and were left feeling tweaked, realizing that Walker’s politics may be in opposition to theirs.

“It pissed off a lot of people, but it was people who I finally needed to see for who they really were,” he says. “I said, ‘I don’t give a fuck if I lose half of my little fanbase.’ The last thing I want is some shitty, racist, bigoted asshole singing every word to my songs at my shows, front row. That doesn’t make them awesome; that still makes them a shitty person. So I was really happy to thin the herd. But it was tough. There were awkward moments, with fans, friends, and family after that.”

Walker doesn’t wade into political issues on Glenn, but he does takes some astute, sharp jabs at gentrification and the influx of new neighbors (himself included) into established communities. “Now they’re mad at folks like me movin’ in/Avocado toast still fresh on our hands,” he sings in “Roll Away (Like a Stone),” speaking volumes with a simple nod to a basic brunch dish.

After living in Los Angeles and then splitting his time between L.A. and Nashville, Walker is now a full-time Tennessee resident. Ironically at this very moment, his home and studio are literally being rattled by construction next door, where an army of excavators are jack-hammering away at the bedrock so a new neighbor can begin building a mansion. Walker laughs at the situation. “I’m the statistic of people that leave L.A. because it was getting too ridiculous and come to the country,” he says. “So I’m like, this goes both ways. I come here to get my space and my peace of mind, and I’m still wearing Vans and a hat and looking for avocado toast, while out here, people are on tractors and at church. That’s what that song is about: No matter what, you’re never exempt. There’s always somebody more annoyed at you than you are at others.”

With the tour just two weeks away from the time of our interview, Walker has much of his gear already packed in cases near the door. He and his band, which for this run features Aaron Lee Tasjan on guitar (Tasjan opens the gigs too), will hit all the cities Walker once or presently called home: Atlanta, Nashville, L.A, among them. There’s a request segment that’s in line with his play-anything-for-tips alter-ego Glenn and, like at Pilgrimage, there are more up-close moments in the crowd and exhortations for fans to dance. It’s a proper show, the kind Walker began to craft when he played the Sunset Strip with his Eighties rock band SouthGang, refined in the Nineties with his “Freak of the Week” alt-rock group the Marvelous 3, and — though he may disagree — has since perfected as a solo entertainer.

“I’ve watched other artists that I love my whole life. Some blow me away and leave me feeling like I left a church service. Others, I don’t ever need to see them again live,” he says, packing up his computer to head to his son’s school, where he’s recording his kid’s band for a class project.

“Years of being in a van and playing to the bartender will either completely jade you to the point of no return, or it will make you try your fucking hardest to win over the bartender,” Walker says. “That was all of the Nineties for me. But no matter the lane you pick, the common thing has been to connect with people in the audience. I get high from that.”