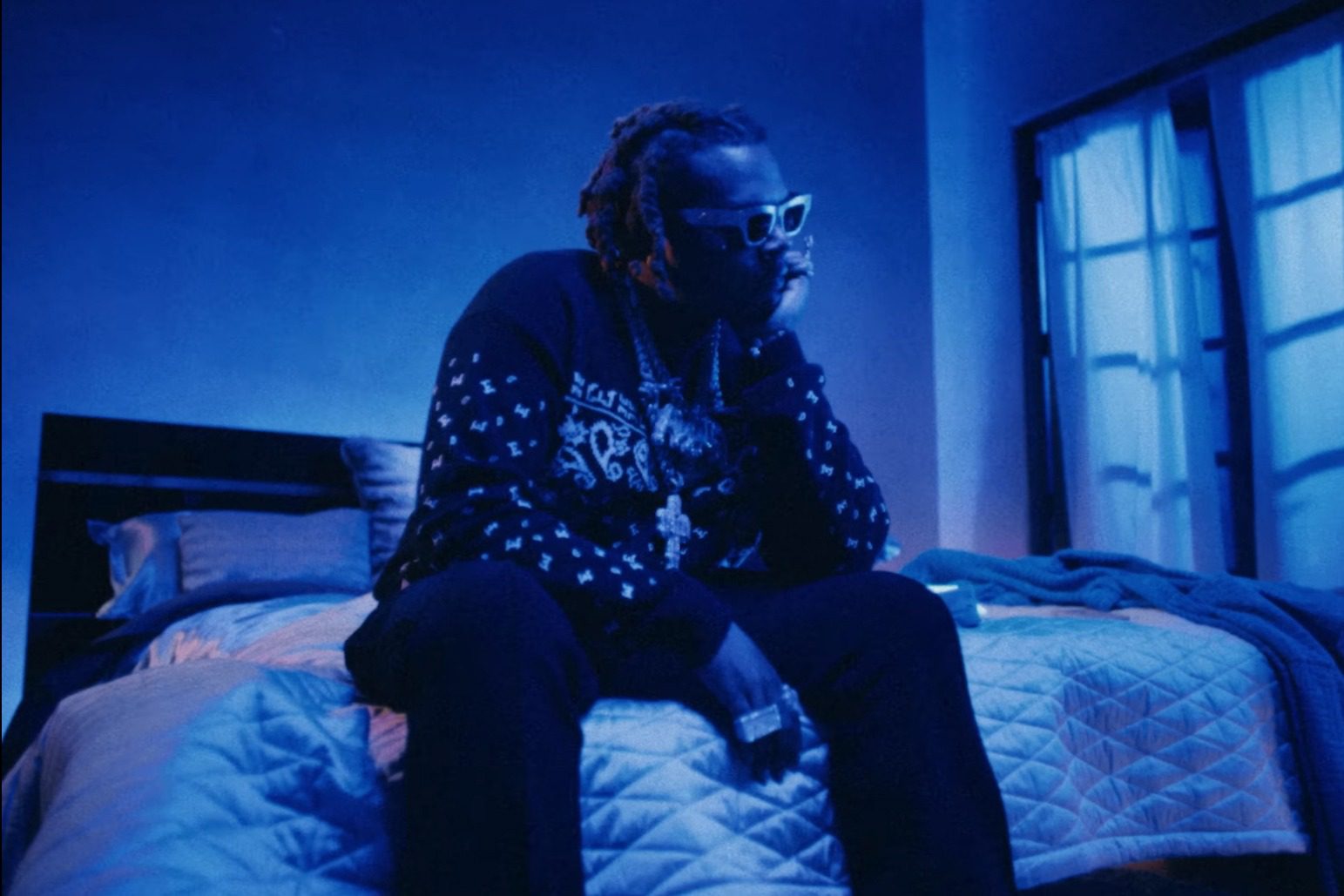

Hulu’s XXXTentacion Documentary and the Cult of Jahseh Onfroy

In a particularly ominous moment from Hulu‘s new documentary Look at Me: XXXTentacion, we see a 19-year-old Jahseh Onfroy, a.k.a. XXXTentacion, make an official-sounding announcement on his Instagram. “I’m going to stop calling you guys fans,” he says. “I’m going to start calling you members of my cult. This is a cult, not a fanbase. This is far more genuine than a fanbase.” Cult leaders, of course, are often more interested in power than they are in the salvation of their followers, and Onfroy, who was murdered the following year at age 20, was indeed formidable at maintaining control over those around him. His followers remain a key element of his mythology — the credits for Look at Me feature recorded video messages from X’s fans about how he saved their life.

Directed by Sabaah Folayan, who also directed the 2017 documentary Whose Streets about the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, Look at Me is comprised of never-before-seen interviews with Onfroy, his family, and collaborators. Much of the footage of Onfroy himself is from a separate documentary produced by The Fader around the time he rose to fame, which was never released; Folayan was brought on later. “It was two years after he passed when I came on,” she says over Zoom. “Any of the footage with his close friends, family, his mom, Geneva, all of the interviews, I shot, with the exception of the very last scene, the reconciliation moment with Cleo and Geneva. That was something that the estate conducted independently.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2],[640,250]])

;

});

The people she mentions by name are key players in X’s story: His mother, Cleopatra Bernard, and his ex-girlfriend Geneva Ayala, who in 2017 alleged that Onfroy abused her over the course of their relationship. The film features extensive interviews with Ayala, whose accusations — outlined in a detailed police report first published by Pitchfork — fueled the subsequent controversy and buzz around XXXTentacion. When Folayan started work on the project, Ayala’s was the first interview she conducted. “I felt a lot more anger toward Jahseh than she articulated. [I was] finding my way of meeting her where she was, which was actually in a place of forgiveness,” Folayan recalls. “Perhaps this is connected to the tremendous amount of public pressure and backlash that she got from coming forward. Who knows what the internal chemistry of her own emotions is?”

Folayan describes her approach to the film in the context of her background in public health advocacy. “I worked at nonprofit organizations and each of my jobs really ended up requiring me to interview people in a clinical setting to understand and unpack their stories and their experiences with trauma,” she says. As a result, she came into the project hoping to paint a nuanced portrait of a highly influential musician. The documentary makes an admirable effort at digging deeper than shocking headlines, unearthing genuinely compelling context about Onfroy’s upbringing, including alleged abuse he suffered earlier in life. But the search for nuance in Look at Me ultimately feels one-sided.

X’s mother and his lawyer, Bob Celestin, are both credited as executive producers on the film, and you can feel an unnerving tension beneath the surface. Nobody seems to have much unexpected to say about X, and as a result, topics go frustratingly unexplored. Whole swaths of his career seem washed over for the sake of cleaning his legacy, like a legal footnote stating that Onfroy was 18 years old when he moved in with a porn star turned rap manager named Bruno Dickumz; no further explanation is given of what this fact means. Folayan admits that working with so many emotionally invested stakeholders made for a number of challenging decisions. “Then there were times where I would agree with what the estate thought, there were times where I didn’t,” she says.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The film is thorough in its narrative trajectory, following Onfroy from childhood to fame, and probing what amount to various theories about what could have turned him violent. “I decided early on that this was going to be a coming-of-age story, more than a music biopic,” Folayan says. The result is an occasional flattening of ideas that could complicate the justifications provided throughout the film by those close to Onfroy. “People who knew him closely saw him as being his own worst enemy — they saw these other aspects of him, where he was really fighting himself and fighting his demons,” Folayan says. “There was this pervasive sense of both allegiance to him and this sense of him as a victim. It was really difficult to work through, because it seemed like people just would consistently talk about him as the victim. Despite the fact that the allegations against him resulted in him being propelled to fame.”

For all of the film’s focus on XXXTentacion’s impact on young people suffering from depression, little is made of the fraught atmosphere in which his fanbase became, by his own description, a cult. There is something unsettling about uncritically lionizing a musician for the sheer fact that they connect to their audience. (Nor was he the first to do so in this way: Tyler, the Creator and Eminem before him both pushed boundaries over what culture deemed acceptable expressions of adolescent rage; Tyler was banned from entering the U.K. for several years.)

In interviews with members of X’s rap collective Members Only, we hear them flat-out admit to using manipulative social media tactics — like making dozens of troll accounts — in order to generate hype. There seems to be a missed opportunity in these threads, as they collide so distinctly with the film’s central image of X as a powerful, almost god-like force for good. “The fans are toxic,” Members Only’s Flyboi Tarantino says in one scene, describing the vicious harassment Ayala suffered at the hands of young XXXTentacion fans after details of her allegations became public. “They’re going to start making their own narratives.”

That narrative, of X as a misunderstood genius unfairly maligned by the media, crystalized when the rapper was tragically killed in an apparent robbery only days before he was set to turn himself in for charges of witness tampering — a charge stemming from his ongoing case after allegedly attacking Ayala.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

In one of the on-screen interviews with X, he’s asked whether he thinks fans should separate the art from the artist. By the end of Look at Me: XXXTentacion, it feels too narrow a choice. Since his death in 2018, the musician has been cast as a singular voice of his generation in ways far removed from X himself. Now, the consistent and often gruesome pattern of alleged violent behavior that he left behind is neatly folded into a tidy story of redemption. In the film’s credits, his posthumous collaboration with Kanye West, “True Love” from Donda 2, plays while a slideshow of his streaming statistics appears on screen.