Inside the ‘Black Market’ Where Artists Can Pay for Millions of Streams

The music industry is famous for being hyper-competitive, but in the summer of 2019, the biggest companies — from major labels to streaming services — briefly united around a common cause: signing a code of conduct condemning streaming manipulation, a practice that inflates artists’ numbers on platforms like Spotify and Apple Music and potentially reduces payouts for smaller acts.

“Streaming manipulation has been an unfortunate blight on the industry over the past few years,” declared John Phelan, director general of the International Confederation of Music Publishers. “There is a black market for pay-for-play.”

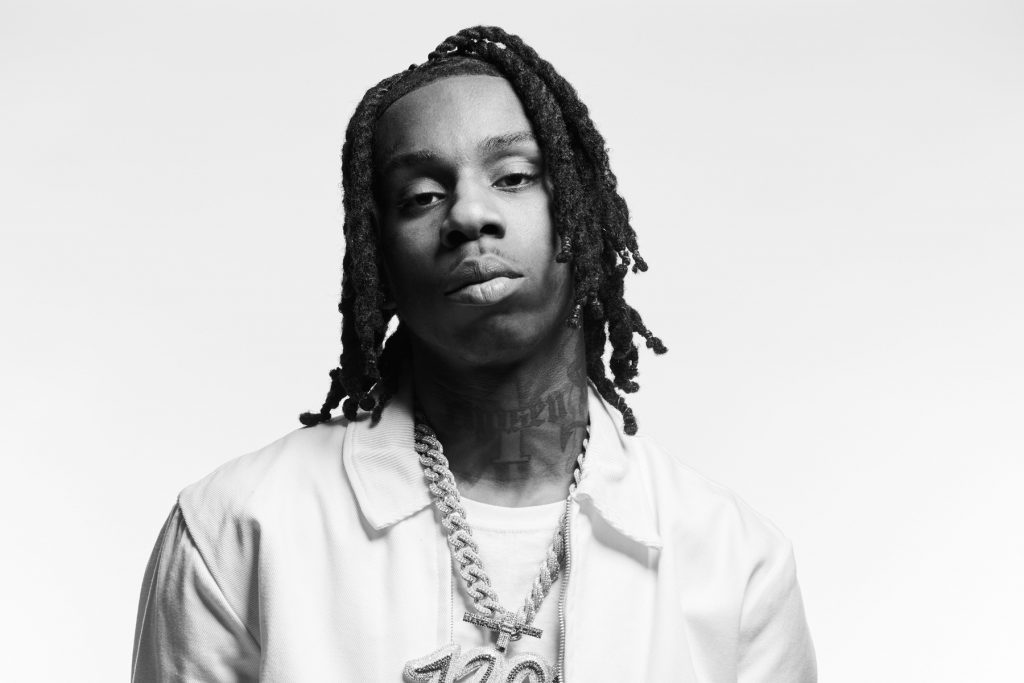

Not long after the code of conduct was signed, various members of the Blueprint Group — a high-powered management and distribution company that works with multiple Grammy-winning artists — hopped on a conference call with a digital marketer named Joshua Mack, according to an audio recording obtained by IndieLand. Two of Blueprint’s CEOs, Gee Roberson and Jean Nelson, the head of digital strategy, Bryan Calhoun, and the chief marketing officer, Al Branch, explored options for boosting an upcoming release from rapper G-Eazy, an artist they manage. “I want this to be big,” one member of G-Eazy’s team says on the call.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Mack tells Blueprint he can jack up artists’ streams — for a price. A salesman operating in an industry that treats hype as standard operating procedure, Mack claims to Blueprint that his “network” can generate “200 million streams a month” spread across its various music clients, a group that he alleges has included nearly a dozen well-known acts and prominent labels. The recording offers a rare glimpse into the shadowy world of third-party companies operating in the music industry, attempting to seduce artists, managers, or labels by promising to manufacture millions of streams.

Mack freely admits to Blueprint that Spotify has punished him for his stream-boosting activities in the past, but he claims that artists continue to use his services anyway. Why? “We basically cracked the code,” Mack says, “and understand how to manipulate the system and hit astronomical numbers.”

Attempts by artists and record labels to “manipulate” sales numbers are as old as the music industry itself. And as streaming has become the music industry’s primary driver, many of the manipulation efforts have moved to the digital sphere, where Mack focuses his services. In a sales deck obtained by IndieLand, Mack’s company 3BMD says it helps with “streaming playlist PR,” “social media PR,” and “music audio PR,” among other things.

To the uninitiated, people who work in streaming promotion might as well speak another language. They praise “save rates” (a valuable sign of listener investment that occurs when a user hears a song and adds it to their personal library or playlist) and “premium” plays (these come from paying subscribers and are weighted more heavily in the charts than clicks from free users), and often use terms like “activate the algorithm.”

But despite the new vocabulary, digital marketers say that some streaming manipulation resembles old-school radio payola: Third parties build or gain control of playlists or networks of playlists on a platform like Spotify and then accept payment from artists or their teams for placing songs in those lists. (Though unlike payola, there is no FCC regulation of streaming manipulation.)

“We agree to a certain amount of money for a certain amount of streams,” says one A&R at a prominent label. “We’re good; we just need performance-enhancing steroids to be a little bit better.”

Other number-fudging techniques are more advanced. Digital marketers say that some companies set up programs to automatically generate thousands of new, bot-like accounts that repeatedly play a song or playlist. This activity doesn’t just lead to artificial inflation of streams (and egos). Due to the way streaming services shell out money — divvying up their pools of cash according to each rightsholder’s portion of total streams — manipulations also lead to lower payouts for some acts that do not engage in this behavior.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

Artists can be penalized in other ways when their tracks are connected to streaming manipulation. This activity goes against the terms of service for prominent streaming companies, which have systems in place to flag plays they believe to be the result of manipulation. In January, Spotify pulled tens of thousands of releases off its platform, claiming that they had racked up “artificial streams.” “Engaging in any way with artificial streams can result in the withholding of manipulated streams from streaming numbers, withholding of royalties, and, where necessary, removal of tracks from our service — so it ultimately hurts an artist’s long-term prospects,” a Spotify spokesperson says in a statement.

At least one of the major labels, Sony Music Entertainment, has instructed staff< that it “prohibits stream manipulation by its employees or any third parties acting on the company’s behalf.” But in some cases, artists or managers may be pulled into manipulation activity unwittingly, handing money to a digital marketing company that claims its techniques for boosting streams are legitimate — by running Facebook ads, for example, or placing songs on playlists that don’t demand payment — only to have their music pulled down by Spotify. “It’s important for artists and managers to know that some promotional services use stream manipulation methods without informing them, leaving artists to suffer the consequences,” Spotify’s spokesperson adds.

“Everybody’s trying to get on playlists; everybody’s trying to get a leg up,” says Chris Anokute, a former major-label A&R who is now a manager and founder of the entertainment company Young Forever Inc. “Most labels hire independent third-party playlisting companies. And it turned out that some of these companies ended up being bad actors.”

But under immense pressure to show streaming growth, even experienced players can decide to look for outside help to manipulate play counts, according to multiple sources in the music industry.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“There are a few third-party companies out there running this for a lot of the major companies,” says one A&R at a prominent label who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution. “We use them too for some of our artists. We agree to a certain amount of money for a certain amount of streams, and we can spread that out among [our] artists. It’s like, we’re good; we just need performance-enhancing steroids to be a little bit better.”

During Mack’s call to discuss boosting G-Eazy’s first-week numbers, Blueprint Group executives — veteran managers with a stable of high-profile acts — directly asked the marketer about his methods for increasing streams.

Joshua Mack: “We Cracked the Code and Understand How to Manipulate the System”

“We’re saving the album and running the numbers up… across multiple devices, all premium,” Mack replies. He also assures the Blueprint team that the streams he generates are “in the United States,” presumably because those plays will count towards the all-important U.S. charts. Another aspect of “running the numbers up” involves what Mack calls “album buys.” He goes so far as to claim that “we bought 8,000 albums” for one well-known rapper.

He does not explain the mechanism behind these supposed purchases. Similarly, Mack says he is reluctant to go into too much detail about his methods for boosting streams. “This is a secret sauce,” he claims. When Mack does name alleged former clients, he never says which projects he might have helped promote, and members of the Blueprint Group rarely push him for additional information about specific artists.

Responding to IndieLand‘s request for comment, Mack acknowledged that he spoke with Blueprint Group, but he declined to answer a list of specific questions related to claims he made on the phone call, saying that he doesn’t recall the details. He also noted that the call was a sales presentation, “and it is possible that some statements may have been exaggerated.” On the audio recording, for example, Mack claims to have worked with a global superstar and hired “the right team in every country across the world” to help one of her rollout campaigns. In his statement to IndieLand, however, he now says that he “never worked with” that artist.

Mack briefly discussed the nature of his work with artists in a statement. “As a marketing company, we have used advertising buys and social media to assist in growing campaigns,” he says. “While I cannot comment extensively on a private conversation that took place two years ago, I can say that I have created a proprietary framework that allows business intelligence to guide in the decision-making process.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Over the course of the freewheeling, 100-minute-plus discussion with Blueprint, Mack mentions a wide variety of acts and labels — including major stars and prominent record companies — that he claims to have worked for.

“If we stop pressing the buttons, the people at the labels would not be able to be getting the type of response and support they’re getting,” Mack says on the audio recording. “That’s the honest truth.”

He also tells Blueprint that artists sometimes take action to boost streams without their labels’ knowledge. Acts can use money earned from live performances or funds earmarked for videos to pay for Mack’s services, he says. “Scoop it off a show; charge it to the music video,” he adds. “Do whatever you need to do.”

The call offers no indication that G-Eazy or his label, RCA, knew that Blueprint was involved in discussions exploring the possibility of boosting the rapper’s streams. Both G-Eazy and RCA’s parent company, Sony, declined to comment.

“If we stop pressing the buttons, the people at the labels would not be able to be getting the type of response and support they’re getting” – Joshua Mack

On the recording, Mack promises that he can play a crucial role in hitting commercial targets. In G-Eazy’s case, he claims to Blueprint that he can deliver 50% more album-equivalent units — a music-industry measure that combines sales and streams — on top of whatever the rapper could earn otherwise. The callers decide that G-Eazy can amass around 20,000 units on an EP opening week. “With us,” Mack says, “you’ll do 30 [thousand].”

He tells Blueprint that the total cost of this effort would be between $30,000 and $50,000. In the 3BMD sales deck obtained by IndieLand, the company offers 1 million YouTube streams for $12,000 and comparable rates for Spotify and Apple Music. (YouTube did not respond to a request for comment.) The deck also claims that 3BMD has had a hand in more than 100 hits on Billboard‘s Hot 100.

It’s unclear from the recording whether Blueprint hired Mack, and the management company did not respond to requests for comment about any aspect of the call. When asked whether Blueprint ended up using his services, Mack did not address the question, saying only that the call had been for the purpose of “establish[ing] a relationship” with the company.

While the F.C.C. prohibits undisclosed radio payola in the U.S., there’s little legal regulation of streaming manipulation. Still, Blueprint expressed “concern” about shelling out thousands of dollars to a third-party company to boost their streams. “My concern is that, how do we protect all of us?” one Blueprint member asks. “The last thing I want is this shit to get so big and the feds are on us.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

An associate of Mack assures the callers that “we’re not putting anybody in harm’s way.” And, he adds, “I wouldn’t be involved if it had an illegal side to it.”

“Third parties that promise playlist placements or a specific number of streams in exchange for money violate our terms of service” – Spotify spokesperson

That being said, businesses that promise streams in exchange for money are beginning to come under increased legal scrutiny. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, a global non-profit group representing the interests of the music business, has succeeded in securing multiple injunctions against sites that offer these services in German courts over the last 18 months. The IFPI has argued — successfully — that these sites are in breach of Germany’s Unfair Competition act, because manipulating play counts creates an artificial impression of popularity and can mislead consumers.

Nothing comparable has occurred in the U.S. yet, leaving the music industry to regulate itself. In a statement, a Spotify spokesperson says that “stream manipulation is an industry-wide issue that Spotify takes very seriously. Third parties that promise playlist placements or a specific number of streams in exchange for money violate our terms of service and encourage stealing legitimate earnings from hard-working and deserving artists and rights-holders. We have taken legal action against bad actors and helped take down artificial streaming merchants in markets around the world.”

Joshua Mack: Spotify “Took All My Playlists”

Similarly, a rep for Apple Music says in a statement that the service “has a team of people dedicated to tracking and investigating any instances where manipulation is suspected. Penalties include cancelation of user accounts, removal of content, and termination of distributor agreements.”

But two people who have worked for years in the playlisting space say streaming companies sometimes end up playing games of “Whac-a-Mole,” shutting down one person violating their terms — either by accepting compensation for playlisting, botting streams, or both — only to have the same person pop up again with a different company.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Mack’s call with the Blueprint Group helps illustrate the challenges streaming services face when it comes to enforcement: Mack explicitly refers to actions taken by Spotify to prevent his activities, but claims he has “figured out” a way to get around the platform’s security measures. “A lot of the [streaming platforms] have gone after people who have been super heavy in this space,” Mack says. “I already went through that crap with Spotify. They took all my playlists.”

But Spotify was unable to identify the person behind the playlists it confiscated, according to Mack. “The paperwork that came [notifying me that I lost those playlists] did not have my name on it or a company name,” he says.

And he assures the Blueprint team that losing a batch of playlists in the past did not impede his ability to help artists boost their streams in the future. “We figured it out,” Mack says. “I build 40 to 60 playlists a week. And they’re going to be consistently being built every week.”