Jack Irons on His Years With Pearl Jam, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Joe Strummer

IndieLand interview series Unknown Legends features long-form conversations between senior writer Andy Greene and veteran musicians who have toured and recorded alongside icons for years, if not decades. All are renowned in the business, but some are less well known to the general public. Here, these artists tell their complete stories, giving an up-close look at life on music’s A list. This edition features drummer Jack Irons.

Whenever the history of the Nineties alt-rock revolution is chronicled, the name Jack Irons comes up quite a bit. Not only is he the original drummer of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, earning him a spot in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but he also introduced the future members of Pearl Jam to an unknown San Diego singer named Eddie Vedder. He joined Pearl Jam as their fourth drummer in 1994, but left four years later due to stress related to the band’s intense touring schedule.

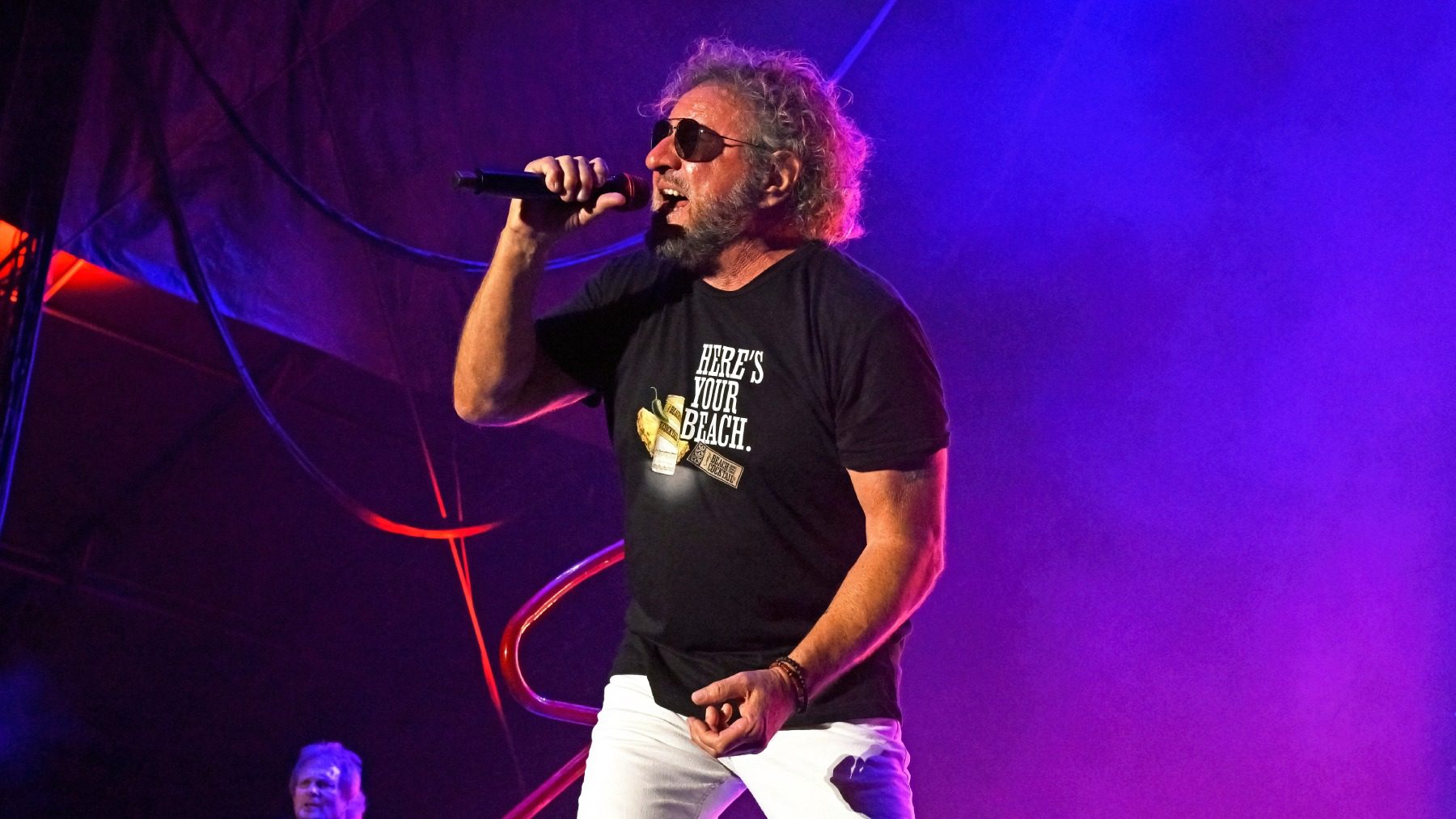

Irons has also played with Neil Young, Joe Strummer, the Wallflowers, Courtney Love, What Is This?, and Eleven. During the past two decades, he has focused largely on solo work and recording projects with former Chili Peppers guitarist Josh Klinghoffer. He recently released the solo EP Koi Fish in Space. We called up Irons at his Southern California home to talk about his long career.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2],[640,250]])

;

});

How are things going? Are things back to relative normal after the worst of the pandemic?

I’m spending a lot of time in my home studio, which is something I’ve always done, at least in the past 20 years. There does seem to be more normalcy and ease of doing things in the air.

I want to go back and talk about your life. What’s your first memory of being a kid and being aware of music?

I don’t know if I have a first memory. My father is a big music fan. He was big on sound. He’d have his own speakers, and he’d build his own cabinets. He would love to play Trini Lopez’s “La Bamba.” That’s one of my earliest memories of hearing music out of a big stereo system. I was like, “Wow, what is that?” That’s probably my earliest memory. After that, it was all the radio. I loved pop and rock hits and whatever was on the radio at the time, like soul and Motown. I just loved it.

Who were some of your first musical heroes?

“Heroes” is an interesting word. It would probably be the Beatles if we’re going to get to that heroes stage where I was really focused on a band. As I said, I was really influenced by hits that were on the radio from around 1969, ’70, ’71. There were a few stations and that’s what you got.

Did you see any concerts as a kid that left a real mark on you?

Not as a young kid, no. I don’t even remember my first show. I didn’t see concerts until I was a later teenager. I remember seeing Santana at the Universal Amphitheatre. I was blown away by the level of musicianship and the jamming quality that his shows were about. I saw Queen at the Forum, and David Bowie. My [What Is This? and Eleven] bandmate Alain Johannes, who is a dear friend, someone in his family had ties to Yes management. And so I saw Yes many times.

I remember seeing the Police. They had a blond concert [on Jan. 16, 1981, at the Variety Arts Center in Los Angeles]. You had to wear a blond wig to get in. It was early days.

What attracted you to the drums?

I don’t know, but it started around 1973. We were moving from one part of L.A. to another and there was a music store with a red-sparkle drum kit in the window. It just caught my eye. I was like, “Wow, what’s that?” I had an attraction to it. I was 10 or 11, but I didn’t act on it until I was 13. That’s when Hillel Slovak and I became friends and decided to play music.

Who were some of the artists that you and Hillel really admired when you first started making music?

When we started making music, we were real Kiss fans. This was around the time of Alive! We were, no doubt, junior-high Kiss fans. We dressed up like them. I was Gene Simmons and Hillel was Paul Stanley.

I’ve read that you guys played a school talent show in costume.

We did. We were real fans. We spent weeks on the costumes. We’d go around L.A. and find the store with rhinestones. We’d sneak around Hollywood Boulevard, where I wasn’t allowed at the time, to find some giant-heel shoes I could make into boots. Then we had to find the makeup. All those things were so fascinating and fun back then.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

This was obviously pre-internet and we were kids, so how do you do it? We figured it out. Before the talent show, there was a Halloween where I didn’t get a wink of sleep. Hillel and I stayed up all night and did our makeup on each other. I’ll never forgot those days. I won that Halloween costume contest that year. We showed up in our Kiss outfits.

What song did you do at the talent show?

We were just miming. This is just us jumping around. We did “Detroit Rock City” and then I think we did “King of the Night Time World,” which is the song after it [on Destroyer].

When did music become more serious in your life?

Hillel and I started taking lessons at 13. We both had no clue what we were doing, but he knew he wanted to play guitar and I knew I wanted to play drums. We just wanted to do it. We could barely play.

My memories are a bit sketchy, but Hillel had met Alain Johannes, who was another high school friend. Alain was great. We were probably six months into our instruments or maybe a year, and Hillel goes, “We should jam with this guy Alain in our classes.” Alain was already a really good musician. He could play anything. He could figure out Steely Dan solos. He was already really advanced, but he was only 13 or 14 years old and he liked us. We all became really good friends and we learned to play and jam together.

Hillel wrote his first song. Alain wrote his first song. We worked them all out together. This was around seventh or eighth grade. Probably by ninth grade we were ready to play with a bass player. We had a set of covers and a few originals. We found a bass player in junior high.

This was the same junior high that Flea writes about in his book. But I knew Flea from elementary school. I don’t know if we were friends. He said I was a bully. He said I drew a nasty picture of him and handed it around the class in the sixth grade. I was a little bit of a bully in sixth grade.

Flea’s memory was you getting into lots of fights.

I guess I was an angry sixth grader. [Laughs] That really changed because, believe me, I’m a sensitive, sensitive guy. By seventh grade, there was no way I was getting into a fight with anybody. Who knows what happened? It was some unconscious childhood stuff.

We didn’t play music with Flea. He was a trumpet player. But we were schoolmates. I don’t remember much of those years. Junior high to me was me, Alain, and Hillel. That was the trio of guys. And then Flea came into our lives in high school.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

There was so much music happening then with funk, punk, very early hip-hop. Are you guys drawing inspiration from all this stuff?

Yeah. … The punk stuff was happening, but I wasn’t aware of it until after high school. I would say all the music coming out was very influential to everybody to one degree or another. I was more of a homebody. I didn’t go out and live in the scene like that. I went out mainly to do my own shows. I was a homebody and that hasn’t really changed.

Music was just in the air. I remember being in high school and we thought we were the shit. There’s always rocker guys around school. One said to me, “You have to hear these Van Halen guys. They are really something else.” I had no clue who they were, how good they were at the time. Their first record came out two or three years later. It was a hell of a first record.

Tell me about the early days of the group What Is This?

We started playing with Flea in high school. Hillel wanted to bring him on board. He really liked him. Flea hadn’t started playing bass yet, but he was a good trumpet player and he knew all about music. It wasn’t hard to put a bass on him and watch him adapt.

We started playing together and it happened real fast. He joined our band Anthem. We did the high school thing. We joined some clubs. We wanted to make a life in music. We changed our name to What Is This? probably around 1980. We started gigging and doing the clubs.

We graduated in 1980 and we were trying to get a record deal. That was the thing to do back then. And we went out and played clubs and tried to attract attention. We were doing that for a while.

But then Flea left and joined Fear. We went through the process of looking for another bass player until we landed somebody [Chris Hutchinson] that was right. We kept gigging at the clubs. It was a regular process of doing shows and hoping something would happen.

There were a lot of small labels coming up. There were alternative labels that major labels were starting like Slash Records. The label that we eventually got signed to was something called San Andreas, which was an offshoot of MCA. They wanted a hip, alternative label.

The music you guys were making wasn’t very commercial. This was the time of Journey and Foreigner.

I didn’t have any sense of that. I just thought we could make it. When you’re playing the music and doing it, I wasn’t objective. I was like, “We can find a spot in this.” I wasn’t really aware of commercial success and how that worked.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about first meeting Anthony Kiedis.

Well, Anthony was Flea’s friend. I don’t recall the first meeting. It was high school. Everybody got to know each other. He was a really good friend of Flea’s, so he became a really good friend of ours. He would come and jam at my house. He’d listen to our rehearsals. He became a friend. It was very high school.

I didn’t get to know Anthony as much in high school. He might come onstage before we played and talk to the audience, say something about the band or a little poem. It was really when the Peppers started that I got to know Anthony better. I think he went to college. We went to different colleges.

There was a lot of pressure to go to college. “What are you going to do when you grow up?” We knew we wanted to make music. All of us decided to go to college to one degree or another. I know Alain and myself went. I don’t know if Hillel went, or Flea, but three of us tried to go to Northridge College. It didn’t last long. I lasted a week. Then we went to Valley Community College. I didn’t see Anthony much in these years. I think he went to UCLA.

What was it like the first few times the four of you played together as the Peppers?

What Is This? was doing a lot of jamming. We were playing clubs. Anthony and Flea were really good friends, so we’d see Anthony on the scene and do things. At some point, those guys were much more out on the scene. A friend of theirs came to them and wanted them to do a show together as a band. All I know is I was asked to play drums with the Peppers: Flea, Anthony, and Hillel. It was a one-off show at the Grandia Room, which was also called the Rhythm Lounge. They said, “Let’s do one song.”

Flea hadn’t been part of What Is This? since 1981 or early 1982. This is now 1983. We got together. There was no rehearsal. We went to someone’s apartment in Hollywood and we all met before the show and did a run-through of what became “Out in L.A.” And since Flea and I did so much jamming in What Is This?, it was all very familiar. It was easy to go over the arrangement. I was playing my sticks on the couch. I knew what I was going to do. Anthony had some words, a rap, and we did it.

If you listen to those early demos you’re on of “Get Up and Jump,” “Police Helicopter,” “Out in L.A.,” and “Green Heaven,” you can so easily hear the DNA of the Chili Peppers sound. You had it all there from the beginning.

Yeah. The formation years were a big part of it. What Is This? spent a lot of time jamming. Regardless of how we sounded and what directions the band took, me, Flea, Hillel, and Alain spent a lot of time jamming. That language really was there when the Peppers started. There was friendship and camaraderie. I always felt a great deal of love for my friends.

Was it hard for you to pick between the Peppers and What Is This? when you had to make the choice?

Well, the way it went was, we did the one show. It was received so well and we had so much fun that we did a second show where we had two songs. We had what was to be “Get Up and Jump” and “Out in L.A.” Then we developed more songs. It was all the songs you just mentioned on the demo.

The Peppers then became something that was real, but What Is This? was still going too. Both bands were going around L.A., but the Peppers really did catch fire. People were really into seeing them. We kept expanding the set and growing. We were doing both bands. That went on for six or eight months. And then both bands were offered record deals the same month, literally.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Hillel wanted us to do both, in a perfect world. We were very young and wanted to do both. We were trying to. We had lawyers saying, “You can’t do this. You can’t sign to two labels. You can’t do that.” We were forced to make a choice and we chose What Is This? since we had been working with Alain since we were 14 years old. It was a long-time commitment. We loved the Peppers, but we couldn’t imagine not trying to fulfill the goal we had to do What Is This?

Was making the What Is This? EP Squeezed an educational experience?

Yeah. We did it at Eldorado Studios. The education part of it was that’s when I learned that in the Eighties, you aren’t going to make records that sound like my favorite records in the Seventies. They no longer had the gear and the type of equipment that would produce the sound I fell in love with that I thought I was going to be a part of. It was digital reverb on your snare drum and all these things. That was my wake-up call. I was like, “What is this?” And of course, New Wave was taking over and everything was changing.

What brought you back to the Peppers?

What Is This? went on. Me, Hillel, Alain, and our bassist Chris Hutchinson finished Squeezed. We did our touring cycle with that. Then we got an album deal and we moved from San Andreas Records to MCA. They wanted us to work with Todd Rundgren. We got a deal with him, working with him on the first LP.

The band did our tours. We did our recordings. And we didn’t take off. We didn’t get real popular. All that was a learning lesson. It was the time when Spinal Tap came out. It’s a classic movie. I remember watching it in the theater and getting really depressed: “Oh, my God, that’s a parody of my life.” I can’t give the movie enough praise. I was like, “Oh, my God.”

It was a struggle. You’re trying to make it and make a living and have a future. We did Squeezed and the record with Todd Rundgren. During the creative process of that record, Hillel decided to rejoin the Chili Peppers. They were doing better. Hillel felt just — even creatively and everything — he wanted to be part of what they were doing.

He left What Is This? during the making of that first LP. We went on as a trio. We did the trio thing and we really tried. We just couldn’t get over the hump. We had some tours. It’s always great to play, but there were some difficult times trying to get through those tours. Around 1986, Alain was making more music with his partner, Natasha Shneider, who became his lifelong partner and my bandmate in Eleven. He was spending a lot more time with her and focusing on what they were doing together.

Somewhere in that time, the record company shifted from what we were doing to Walk the Moon. That was the name of the band they were establishing at the time. What Is This? was a bit in limbo with what would happen. It’s all very vague to me [in my mind] and it happened fast, but the opportunity to rejoin the Chili Peppers came up, so I did.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about the making of The Uplift Mofo Party Plan. There are so many great songs on that record.

The Uplift was the excitement of the original four being back together. When I rejoined, we did a lot of touring. It was a heck of a lot of touring. Crazy amount of runs. We were all in a van pulling a trailer. I remember one run that was 50 shows in 56 days, or something crazy like that, all in different cities. It was wild stuff like that.

With Uplift, we spent a lot of time in pre-production. We were working with Michael Beinhorn. We spent a month on pre-production. Then we went into Capitol Studios. That was really exciting. I don’t think any of us had been in a real official studio like that. The Squeezed record was made at a small studio. The LP with Todd Rundgren was in his home studio.

We were in Capitol. That was a real fun learning experience. I loved it and learned a lot about the studio and was really happy to be there doing it that way. There was a big room and equipment that knew what it was doing [laughs].

This was the peak of hair metal and you guys were doing something so wonderfully different.

From my perspective, we were just doing what we do. I was always just the drummer. Everything I did was a little bit of anti whatever was going on. In the Eighties, it wasn’t hard. It was a rock guy that loved the Sixties and Seventies. It wasn’t hard to be anti everything that became popular in the Eighties. We were also young and full of spunk and energy. It was easy for me to be offended by some New Wave hit on the radio that had drum machines. I was a punky kid going going, “What? This is not good!”

You took songs by Dylan and Hendrix and put a real Chilis spin on them both.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” was totally different. We took a totally different approach and made it a different song. We had to adjust the song so that Anthony could deliver all the words Bob Dylan created. We adapted the groove. We were always jamming and we came up with stuff. “Fire” was just “Let’s do ‘Fire’ fast.” That’s all I remember.

Was hip-hop a big influence on you guys? It was exploding at this time.

I can only speak for myself, but I’d say yeah. Hip-hop was up and coming. I think for Anthony and Flea and Hillel, they would always introduce me to different things. I was more of a rock guy in the sense of what I listened to all the time. I would be at home more listening to records and practicing drums. That’s what I did. I was never too into what was up and coming, and what was new and what everyone was talking about. I’ve never been really into that.

I’m sure after the tragedy of Hillel’s death, you felt you had to leave the band. Staying around would have been painful.

Yeah. I was really blown up. That became the most difficult period of my life. It defined, honestly, the rest of my life. We had toured so much. I was so tired. The road … doing 200 shows in a year in a van … I just became real tired. I didn’t adapt to all that very easily.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

There was a certain level of exhaustion and personal difficulty I was experiencing leading up to Hillel’s death. When that happened, that was really the breaking point for me. And I went on a much different journey at that point that was all about getting my life back and my feet back on the ground and figuring out what I wanted to do. Music just couldn’t be part of it.

If anything, I was blaming music in a lot of ways, since the life was so un-grounding. “Maybe if we’d worked less, the worst wouldn’t have happened.” I don’t know. Who knows where my mind was at at the time? But it was a very difficult event that sent me down … Life became much bigger at that point. “What is really happening here? What is life all about?” It became really deep and consuming.

I knew I wasn’t going to do music for a long time. That’s why I left. Ultimately, I just couldn’t see myself doing it. I just wasn’t … I couldn’t.

You started playing with Joe Strummer just about a year later, though.

All of this was happening fast. It’s funny. Looking back now, it all sounds like it went on for years. But it didn’t. Hillel passed in June of 1988. I went on my own personal, difficult journey. I tried to do music in the months after. I moved away. I left L.A. About four or five months later, I stopped playing drums altogether. It didn’t even matter to me anymore.

And then the opportunity to play with Joe was huge. I wasn’t going to do music anymore. I was in a dark place, a bad place. And here comes a chance to at least go audition, to finish [Strummer’s album] Earthquake Weather. They were having trouble finding the right drummer to do what he wanted to finish the record.

He was working in Hollywood. I was a big Clash fan. I loved Joe. How could I say no? All of a sudden, it was the universe saying, “You can still do this.” Because it was Joe and because I was a fan, I couldn’t say no to at least trying.

I went to the studio. I hadn’t played in months. I was a shell of a person. They had a drum set there ready for me. I was so nervous, so filled with nerves and anxiety. I could barely play. I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t use my limbs correctly.

I was about to say, “I’m done guys. I’m toast. I’m going to leave.” They went, “Let’s just do a song.” The song was “Jewellers & Bums.” Apparently he tried to cut it with a bunch of different drummers. It was a very simple song with a little half-time break in it. I just played what came instinctually. Once the song rolled, I knew how to play. By the second take, I cut the take. He was really happy with it. He went, “OK, take some time and get yourself together and come back and finish the record.” That’s exactly what happened.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about the tour. He hadn’t really played Clash songs since the Clash. What was it like to play “London Calling” and all those other classic songs with him?

It was great. All that got back me back on my feet, got me playing. We did “London Calling,” but I think the songs that were the most fun for me were “Pressure Drop” and “Straight to Hell.” Those were fun songs to play. We did “I Fought the Law.” All in all, it was really fun to be back and be touring. I was learning.

Working with Joe was very different. Before that, I was in bands with my friends. It was that sort of family feeling, camaraderie. With Joe, I didn’t know Joe. Joe was older than me. He had already lived and worked through the business and had all his learning that way.

It was really the bass player, Lonnie Marshall, that told Joe to try me out, Lonnie and [guitarist] Zander [Schloss] … we knew each other, but we became friendlier. It wasn’t like we grew up together. I had this huge comfort zone working with What Is This? and the Peppers since we were high school friends. So this was different. You hit the road with people you don’t know, you get your own hotel room, you see everybody at the venue or at van call. It’s a different experience.

Of course, Joe was putting together his solo career post-Clash. He was going through whatever challenges and adjustments he was going through. It’s probably a lot of leaning and growing.

The story of you meeting Eddie Vedder at the San Diego stop of the tour has been told many times. We don’t need to get into it in great detail here, but he was a gas station attendant working nights as a roadie. You were drumming with a rock icon and had just left the Chili Peppers. What drew you to this total stranger and caused you to befriend him?

I don’t know. We just hit it off. He was a really sweet guy. We just liked each other. Everyone was really young. In those years … how old was I? 26? 27? Meeting someone and it’s like, “Hey, I like you. You like me. Let’s be friends. …” There was still a little bit of high school in us.

When men get older, other things bring them together than just that feeling. People move on and get married and have kids. It changes. There was still a bit of that. For whatever reason, we wanted to hang out after [the concert]. We had basketball. We both liked music. It was fun to make new friends.

It was interesting because on that same Joe Strummer tour where I met Eddie, at the gig before in San Francisco, I met my wife-to-be. And we’ve been married now 31 years. That Joe tour was really instrumental. I met her in San Francisco. We had a day off and I came down to [San Diego] and met Eddie. It was a setup of my whole future right there in a four-day span thanks to Joe.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid8’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

How did you know Stone Gossard and those guys up in Seattle?

I didn’t know them. They knew of my work with the Peppers. Post–Green River, they were looking to put together a new band. I don’t know who told them they wanted to speak to me. I don’t know how that worked out. I remember meeting Stone and Jeff [Ament] at their hotel. They came to L.A. to do whatever they were doing, and I met them. We talked. They asked me about playing with them for their new band, trying it out.

I had so many things going on in L.A. Post–Joe Strummer, I had started my band Eleven with Alain and Natasha. I was putting a lot of time and energy and love into that. As I mentioned, I met my wife-to-be. By the time I met Jeff and Stone, she was pregnant. The gig required uprooting and going to Seattle. I couldn’t do it. I had already committed to doing a tour with Redd Kross for like three months and I really needed the gig.

They gave me a tape and said, “We’re looking for drummers and singers.” I said, “OK, cool.” Eddie and I had been hanging out. We’d become friends. He was in bands and he was a really good singer, and I knew it. And so I gave him the tape. That was pretty much it.

It must feel great to have done something for someone that changed their entire life. He had so much potential, and because of you he was able to actualize it.

I never thought about it like that. You’d have to ask him [laughs].

But from your perspective, to know that you sparked that fire …

Honestly, I never thought of it like that. I look back at the whole period as a time of happenings. I was part of a lot of things that were happening. I take no credit in that sense that I did something. I was part of something. And as it happened, I got to partake in that years later to help myself and my family and my career.

There was just something in the air. If you look back at the Peppers to Joe and all these things, all these things happened over the course of three or four years. It was just the time. That’s how I look at it. I don’t look at it as anything I did. I’m just thankful my drumming and the music I was part of was able to connect all these dots.

Were you stunned in the early Nineties when Pearl Jam and the Chili Peppers, along with these other once-underground bands, were suddenly mainstream? That shift was very quick.

Absolutely. No one expected that. It was an explosion. It just happened. From a point of view of being in L.A. and trying to make it with Eleven and working hard and always trying to succeed, when the scene from Seattle started to explode, it was remarkable.

The record business was somehow gearing up for that. From a business point of view, to sell the kind of records that Nirvana sold and Pearl Jam sold, something was gearing up that I wasn’t focused on. It definitely did burst through in Seattle.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid9’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

How did you grow during your time in Eleven?

It was a good trio of people. We played well together. Alain and Natasha were really high level musicians. As a drummer, I got to feed off that and rise to the occasion. They are deep musicians, capable of a lot. I don’t consider myself as capable a drummer as they are at what they do. It was great for me since they loved to rehearse. We just grew and worked and did our best to have success.

How did you wind up joining Pearl Jam?

It was 1994. Eleven started right around the Joe Strummer era. That’s when I gave the tape to Eddie. Pearl Jam had three drummers by then. Two [Dave Krusen and Dave Abbruzzese] were official in terms of making records, and then Matt Chamberlain for some of the touring. During this time, I maintained a friendship with Eddie. We talked about me maybe me being part of it.

As I mentioned, my son was born. I remember asking, “How long are you on the road for?” He went, “Well, we’re booked for maybe a year and a half straight.” I was like, “Any breaks?” He goes, “Not really.” I was like, “I just can’t do it. I can’t leave my family.”

I had a hard time in the post-Peppers period because of all that intense work. It was a grind. Also, I loved Eleven. I had a lot of reasons to stay in L.A. and not take that on. … I’m not saying I would have been a shoo-in, but we talked. I couldn’t see myself doing it. But I maintained my friendship through the years.

In 1994, Eleven had done two records. We had just finished a touring cycle opening for Soundgarden. We felt that we had our best shot at some success with that second record and a song called “Reach Out.” We felt that something more could have happened, and it didn’t. We had a great time opening up for Soundgarden.

My wife and I made the decision that we wanted to move out of L.A. before our son turned five. I wanted to get out of L.A. my whole life. I was born in L.A. At some point in that time on tour with Soundgarden, we bought a little cabin like 500 miles away in Norman, California. And so my wife moved whatever we had up there.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid10’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

This was June of 1994, I think. And when the Soundgarden tour ended, I went up to our cabin. I never went back to L.A. What I was going to do with my future at that point was a little unknown. I had to be prepared to do other work to make money. I’m a father now. I’m a homeowner, or at least a cabin owner.

Making music wasn’t getting the job fully done. I was uncertain what I was going to do. Eleven was an L.A. band. We rehearsed all the time. How is that going to work? It wasn’t even discussed, but there was a lot of uncertainty. And then around August of that same year, I heard Pearl Jam had moved on from Dave Abbruzzese. I decided to call and ask if they were going to be looking for new drummers, and to give me a chance.

How did that process play out?

Well, I think they were in the process of playing with different people. Each of the guys had someone they wanted to see. I came in. Eddie brought me in. We jammed. I spent some time with Stone. I stayed with him. We were jamming in his basement. I believe that’s where we recorded “Hey Foxymophandlemama, That’s Me.” At least, we recorded the jam that became that.

They had a Bridge School show that was coming up, so they used me. I think I officially got in there when we did the shows that we were on before Neil Young at a benefit concert in Washington, D.C. I think it was a Gloria Steinem event. That was my first official, “He’s part of the band.”

And then the Neil [Young] thing happened right away. We played a song with Neil and did the Pearl Jam set in D.C. That was my, “OK, I think I’m in the band.”

As you said, Mirror Ball happened right after that. It must have been overwhelming not to just suddenly be in Pearl Jam, but now you’re making a record with Neil Young.

Yeah. It was. It was a lot. I was a huge Neil fan. I was the guy that had these old cars with these loud stereos driving through L.A. playing “A Man Needs a Maid” and some of this less-rocking hits, which I just loved. I was a big fan growing up of his whole catalog. I was nervous, no doubt, going into the studio for those sessions. You can ask my wife. I probably really tortured her. She said she got some fever blisters since she got so stressed out for me.

You made that record in a matter of days. It was all so quick.

We did. And I was full of nervous anxiety. But Neil wrote songs that got us to do that real fast. We were probably all nervous to play with Neil, but I was more nervous since I had less experience. Pearl Jam had been working at a pretty high level by the time that I joined. I was adjusting. But Neil wrote those songs that required us to play pretty much straight-ahead. We just had to stay with the song and really pound it out. He knew that’s what he wanted to get out of us after doing that gig. So he wrote songs that suited the session. It was easy. It just flowed.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid11’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

I love all those songs, but “I’m the Ocean” is my favorite. It’s really a lost masterpiece.

It’s a great song. It’s solid, steady, and just keeps moving. When we played it live, we didn’t know if it was going to last five minutes or 12.

His big thing is that the first take is usually the best take.

I agree with that. I know for me as a player that once I knew something in the first few takes, there’s an energy when it’s right at the edge where you almost know it, but haven’t gone over the edge of knowing it too well.

How was the European tour you did with Neil in the summer of 1995?

That was really fun. We played some interesting places. We played a couple of shows in Israel. We played places a lot of bands don’t go. I remember Prague. We were in a hockey rink or something. We played some pretty cool, interesting places. We did some big festivals like Reading. Those were all fairly new experiences for me, for sure.

I’m sure as a longtime Neil fan, to be playing “Cortez the Killer” with him and whatnot must have been a blast.

It was great. All those classics songs, “Like a Hurricane,” “Cortez.” He would really draw them out. He wanted to present them live in a way where we could all play them well. He played them a particular way. He had so much music. He could play with an orchestra or some really seasoned guys, like he had, or he could really rock it. He could go all sorts of ways.

Brendan O’Brien on the keyboards was a nice addition to the band too.

Yeah. Brendan is just a great musician. He can play anything well. He can pick up just about any instrument and play it well. But he is a piano player. He was really happy to do that.

I really love No Code. It’s one of my favorite Pearl Jam records. How was the experience of making it?

It was great. We did a lot of that in Litho [studio in Seattle, owned by Stone Gossard]. I love the studio and I love the time we got to spend there. Obviously Brendan was producing. It was great to spend a lot of time in an environment where you could find the balance of getting things right, but you also don’t lose the energy. Hearing music back the way you imagined or wanted to since Brendan and the guys working on the equipment would reflect a sound that you wanted to hear.

Brendan taught me to put towels on the drums, like Ringo did. I was fascinated by that since those are the sounds I love. I had a really good time. I remember doing “Off He Goes.” That was a special moment. It was late at night and we caught a moment with sound. That’s what I loved about music.

You’re credited as a co-writer on “Who You Are” with Stone. Do you recall making that song?

Yeah. I always had this groove I liked to play. It was my best interpretation … When you listen to great jazz drummers …Max Roach would play like he had four different limbs that each have a brain. I’m like, “How the hell do you do that? I can’t do those things. I gotta come up with something, I need to come up with some syncopation that’s unique.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid12’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

I like to make everything in the form of a groove and a beat that’s more rock. The “Who You Are” beat was something I had been working on for years, with a pulse that has sort of a heartbeat feel. I was probably jamming it and brought it into the room and went, “How about something like this?” And then Stone went into his part. It took off real fast. I think Stone just wanted to leave it freshly captured.

You and Eddie are credited on the song “I’m Open.”

I was getting very experimental at the time. I started getting into my own weird music. I had a four-track and I loved experimenting with steel drums. I love the four-track since you could slow down. You could slow down the tempo, and I could do it in my home basement studio. I loved the sound. I love the sound of steel drums slowed down.

I created a steel drum piece. I was living in Seattle in a basement. I really liked it. I brought it into those sessions. Eddie wrote a song over it.

You guys went out and did that tour of non-Ticketmaster venues. It was a noble cause, but I’m sure it was challenging at times to play those non-traditional venues.

I think there were a lot of challenges for the organization as a whole. I wasn’t as privy to it. All those guys were really seasoned. They’d been playing big places for a lot longer. They had all that knowledge and all that experience that I didn’t have. And so I was just part of the band and went. There was a lot of that in the beginning for me with Pearl Jam. I was learning. I’d hear about the challenges in certain situations, but I wasn’t involved in the decision making.

One of the great things about a Pearl Jam concert is that any song in the catalog could be played at any moment. For you as the new drummer, you must have had to really be on your toes.

Yeah. I tried to practice a lot, but I was always pretty nervous about that. It takes a long time to learn all the songs, and then also get comfortable playing them. My feel is also very different than every other drummer before me. The songs are going to sound different, so they have to adjust to my feel. That process does take time. Pearl Jam liked to just go for it. There wasn’t a lot of, “Let’s hammer this out and work this out prior.” They were in tour mode. They had done a lot of shows before I joined.

That was part of it, and I kind of got used to it. I probably didn’t adapt to every song well, that’s for sure, but that’s just part of the gig.

Tell me about the Yield sessions.

My sense of Yield is that we were smoother somehow. We had played, we had toured. We were set up. I think we did most of Yield at Studio X, which is Bad Animal [in Seattle]. I think we had a bigger room there. We had bigger, roomier sound than on No Code. I set up a stainless-steel drum set that really had that live snap. That all played into the recording process.

My sense is that we were more musical, more comfortable, dynamically playing a little more relaxed together than No Code, which had more anxiety in the air and a lot more energy. Yield was smoother to me. I guess that would be the best way to describe it.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid13’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about “The Color Red.”

That’s another one from my four-track recordings that I did at home. I started with some drum pattern that I slowed down, sped up, and did some stuff on it. I was always trying to get my mine in. I was always trying to get whatever I was doing to be part of the band. They were very good about that, about indulging me. You’ve got five guys and everyone had a creative spark. That was one of them. It somehow came out as a good little interlude, and Eddie came up with a vocal for it. That’s really how that happened.

Why did you leave the band?

A similar pattern, though without a tragedy like the Peppers years. I didn’t handle stress on the road well at the time. I had a young family with two children. I was just getting really exhausted. It was some deep-place exhaustion. That’s just sort of my MO. Pearl Jam was ready to come back full-swing and hit the road. This was post-Ticketmaster and they were like, “It’s time to hit the road.”

We went to Australia, and I just struggled there. I struggled to find my balance, to get my rest, to recover, to be ready for the next one. It was a lot of pressure. I take what I do seriously, and so does everyone in that band. These were giant shows. It’s very important to have a good show and to do your job well up there. I was having a hard time. I’ll just say it: I was having a hard time with my state of being, without getting too deep into that.

I was due for a pullover. I was ready to pull off the road and take a different journey, a healing journey, and really try and get together certain aspects of my life that I had not really done. I had been pushing myself and running on fumes. It was time.

I had two children and a long future I hoped to have. I didn’t think that I was going to get through it. They had like 50 shows booked that summer in the U.S. I remember we pulled off in March. I just knew I wasn’t going to recover fast. I just knew I was in for a long journey, if I was to be able to find my feet again and be a good father, husband, and be grounded and not a wild, stressed-out guy.

I knew I couldn’t do that tour. I knew I couldn’t do it and feel the way I felt in Australia. There were too many shows. It was too big a commitment, so I stopped. That’s it. I said, “I have to pull off the road for my well-being.” And so I did.

Tell me about making your solo 2004 album Attention Dimension. I know you spent a long time on that.

I did. After I stopped playing with Pearl Jam, I still wanted to be creative. I remember my family and I were on a trip to another country. We were in Greece. I brought a guitar with me. Somewhere on that journey, I felt like I needed to really be creative again. And so I started writing songs. As soon as we got back, I got off the plane and I literally drove right to the Guitar Center in San Francisco. That’s when digital technology was taking off. I got myself the equipment that allowed me to start making my own music. It’s something I felt like I had to do.

I didn’t do anything creatively for a while after I left Pearl Jam, so this is about 1999 or 2000. The first song I had was “Water Song,” which was just this long groove that I had. I started working on that, and I just kept going. Probably around 2001 or 2002, we moved again. I wanted to get all my friends on it. I thought it was fitting. I felt a need to connect to everybody. Everyone was willing to contribute. And so on that record you have contributions from Alain and Natasha from Eleven, and from Eddie and Stone and Jeff and Flea and Les Claypool.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid14’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

I really dig the cover of “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.”

Being honest, the drums for that one were recorded in 1995 at a small studio in Seattle when I was living there. I had this idea for a remake, and so I brought some timpanis in. I didn’t even get the arrangement right. It was all in my head. I recorded all the drums for it and put all the timpanis on. We were all surprised I pulled it out. It took all the musicians to make it come together.

How was your experience in the Wallflowers? You were with them for a bit in 2012 and 2013.

I enjoyed a lot of it. I enjoyed making Glad All Over. They treated me really nicely. I always felt like a guest, in a sense. I was a band member, but those guys had been in a band for years, with all the ups and downs that comes with that. I was a guest. I enjoyed our creative process in the studio, for sure.

We hit the road, but the comeback didn’t get over the hump. And like everything, there are consequences for that. But I enjoyed that. Those guys have a little bit of a history [laughs], but that’s cool.

How about recording with Courtney Love on Nobody’s Daughter?

That was Michael Beinhorn bringing me in. They had already recorded a version of things, and Michael was heading up that project. That was me really being a drummer from Michael. I spoke to Courtney. We had some nice conversations. I just closed my eyes and played the music. That’s it. That’s what I like to do. And Michael thought I was the right guy to help finish that record.

The Chilis got inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2012. Did it surprise you that you were inducted too since your time with them was so brief?

No. I don’t remember if I was surprised. I was grateful. Flea called me and said, “I think we’re going to go in. Do you want to come in? Do you want to be part of this?” I said, “Of course.”

How was the night?

It was a fun night. I had been to one Hall of Fame event before when Neil was being inducted. That’s when I was new to Pearl Jam. That was different. That was in the [Waldorf] Astoria in New York and it was a small event in a ballroom. It wasn’t a big televised arena thing. The Chili Peppers one was the first of the big HBO televised ones in a big room event. It was really different in that sense.

But it was great to be a part of it. People enjoyed it. I get it from the original point of view. No doubt, the Peppers have a story of one lineup being the original friendship, and then two other guys come in [Chad Smith and John Frusciante] and they really helped them take it to the next level.

That night, you played “Give It Away” with Chad and Cliff Martinez, the drummer who originally replaced you. How was that?

That was fun. It was fun for whatever you could hear. You don’t have a lot of time to rehearse so you can hear right. You just go for it. It’s just fun to be a part of it.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid15’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

You were in the house with Pearl Jam on their induction night. What was that like?

That was really sweet too. It became clear there weren’t going to be four drummers inducted for Pearl Jam. But Eddie said, “I want you to come and be part of the night.” And he said some really nice things, and that was awesome.

You played “Rockin’ in the Free World” on the same kit as Matt. You were up there with members of Rush, Yes, and Journey. That must have been pretty overwhelming and crazy.

That was fun. I was just fuckin’ on the floor tom. It honestly wasn’t part of the plan. Let’s just say that there were a few people close to the Pearl Jam family that were pushing me. “Come on Jack, they want you.” I was like, “They do?” Matt and I had talked about it. He asked if I wanted to play. I said, “No, this is your guys’ night. I’m good.”

And then they were like, “Come on, let’s do it!” I just went up there [laughs]. It was so chaotic in that moment. They were like. “Yeah, yeah. Just play the floor tom.” I literally did not have time to think anything. It wasn’t part of the plan.

Tell me how you got together with Josh Klinghoffer and started making music.

That goes back to my solo show. Around 2016, I started to put a lot more work into developing my show so I could perform it live. I had Flea come over to my house and I played it for him. He dug it. He said, “It would be cool if you could open a Peppers show or two one day.” I was like, “That would be awesome.”

He got me on the first leg of the Getaway tour, the U.S. leg of it. I was going to do the first leg. I did about 10 shows with them. The first show was San Antonio. It was pretty wild. These are arena shows, big. And Josh, of course, is in the band. He apparently was a big supporter of the idea of me being part of it. I traveled with them. I became part of the band party. Of course, that was awesome and it really helped me because I don’t think I could have done it any other way.

In that time is when I got to know Josh better. He drew a lot of influence from my era of Pearl Jam with him as a teenager and a drummer. I didn’t know that at the time, but we got to know each other. Josh has grown into being a great musician on his own, so it was natural. It makes sense. “Let’s start to make music.”

It’s interesting that it’s two guys who were in the same band, but about 30 years apart.

[Laughs] It’s true. But when I’m hanging out with the Peppers, I don’t feel like I’m part of the band or I was part of the band. They’ve grown in so many ways that I haven’t been there for. I just feel like an alumni. I know I’m an important part of what was when we were young, but all that stuff was just happening. I just see everyone as musicians.

I did that first run with them and it turned into a six-month run opening up for them. I spent a lot more time with anyone. And Josh started sitting in with me for “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” He came out every night and sang on it. We made a plan to maybe record together one day. I was living in North California at the time and Prairie Sun Studios, where Tom Waits records, is a studio he wanted to do something in. We did To Be One With You there and it was really fun.

Now he’s sitting in with Pearl Jam, too. He’s now played with both of your bands, but years later.

Full circle. I don’t know how those things happen. It just shows … I’d like to think it’s just a little bit of magic that exists. I like to look at it as a little bit of good fortune and magic in the air.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid16’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about Koi Fish in Space and how that started.

Through all these years, I did solo music. When I feel a creative period, I tend to jump on it. Of course, it takes a lot more to finish it than the juice I was feeling when I said, “Let’s go for it.” When you’re doing it yourself, there’s so much from the technical side that it takes from you.

Koi Fish is another expression. And through these years, I’ve had four records I put out one way or another. A couple years ago, I put out one called Dream of Luminous Blue where I had a little bit of a run where I finished about six tunes and released an EP. With Koi Fish, I started another one in a different location and finished it. I played it for Josh. He loved it. He actually hooked me up with Org Music. They dug it and wanted to put something out. We put out the last two EPs together as part of one LP. Now we’re here.

It’s a great showcase of your drumming.

Everything starts for me with the drums. All these years, I’ve been developing the concept. … I don’t play any other instrument really well. I’m always like, “What can I do with these grooves or feels or sounds? How can I go somewhere with them?” Through the years, I’ve been experimenting with them. And I love that. I love the random element of creation that just starts with the drums.

I’m sure it’s been very satisfying to watch your son Zach’s career take off as the guitarist in Awolnation.

Yeah. It’s great. From a very young age, he wanted to be a musician. He’s very talented. He’s a great drummer. He rarely plays, but when he sits down, he can really play. That’s how he started.

Both my children are really into the arts. My daughter is a video director. She did a little video for me, but she’s done video for John Frusciante and a couple for Awolnation. There’s just a lot of artistic genes in the family, for sure.

Do you see yourself back in a rock band at any point in the future?

That’s always possible. To me, those things happen naturally. The timing’s right and you meet somebody and they want to do it. I see that as a little harder as time goes by and getting older in terms of an original band. I’d love to do some more playing with Josh. I’ve been a big part of his catalog, and so I’d love to do that. But Josh is playing with Pearl Jam. He’ll be very busy doing that for a long time, it looks like. They have some tours coming. And so it’s hard to say. I love playing with people. I definitely miss it.

We’ll see how all that comes back into the world and how age plays into it. I try to put as much stuff out there as I can. I do little sessions at home, and I love that. I love playing to other people’s songs and getting the job done easily and they’re happy.

When people leave bands, the friendships often dissolve. But you’re still close to the guys in the Chili Peppers and Pearl Jam. That’s rare.

Right. Well, I love everybody as friends. You just make sure you don’t sue your friends [laughs]. That’s a bad joke. In other words, things [with some bands] get very sticky around money and finances. I’m not saying I understand any of it. I just know things go south when the business part of it really steps in. I think there’s a fair way for everything. I’ve always truly loved my friends and I treated them as friends and I talk to them as friends. I think they do the same for me.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid17’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Do you ever think about writing a memoir?

Sometimes. But I do think … I’m obviously willing to talk for interviews, but I don’t like to do it. I don’t like to go over all the past. I live in the present moment. A memoir? What would it serve? I’d have to go deep in a lot of other areas that would be … Maybe everyone has heard some of this stuff, though I guess not all together at once. They know the histories of the bands. My story is probably much more … As they say, the devil is in the details. I just don’t know. Everybody has a story. Right now, there’s just so much information out in the world. I don’t know.

Look, if I ever get inspired. If I’m ever like, “I feel inspired to do this.” Like Flea wrote his book and I was there when he was writing a lot of it. He was inspired to write a literary work. I’d have to have some inspiration that isn’t, “I want to make some money” or “I should do it” or “People should know.” I tend to be inspired by doing weird sounds with weird music that doesn’t fit any form, so words are very foreign. I just haven’t found that motivation yet.

What are your future goals?

I would love to see some of this music open some more doors of opportunity for me to work. It would be nice if it somehow could find its way with visuals. I can’t say I’d necessarily be touring. It would be fun, but tours at this point are me playing to backing tracks with visuals. That all has to come together in a particular way to work out with the logistics of touring.

I would say in the film and TV world, if somehow my weird music could find a home … it feels to me like the world in general, even with all this technology and digital possibility, as an avenue for artists to create as they want, it still feels like we’re going in a more commercial direction in terms of what actually gets used and creates money-making opportunities. I do what I do as an artist. My goals? I don’t know. Probably a lot more meditation, or something.