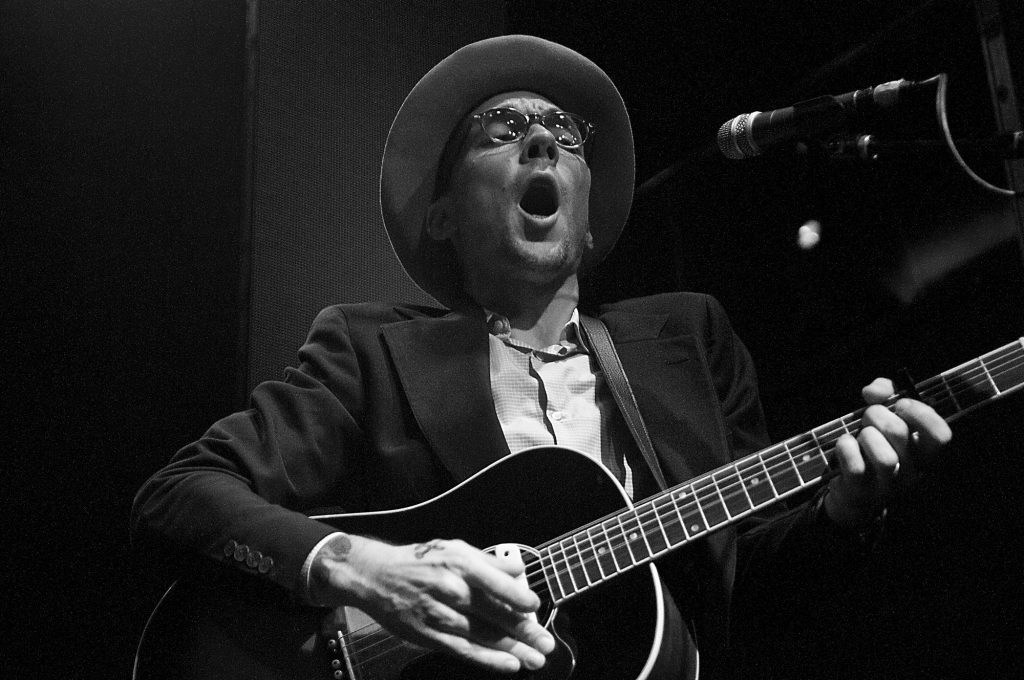

Justin Townes Earle: The IndieLand Interview

Last June, Justin Townes Earle sat down for a typically frank and hilarious interview on our IndieLand Music Now podcast. Townes Earle had a lot to celebrate: an excellent new album, The Saint of Lost Causes, and a two-year-old daughter, Etta, at home. In a free-wheeling, emotional conversation, Earle — who died at the age of 38 over the weekend — looked back at his rough childhood, discussed his relationship with his father, Steve Earle, his “bumpy” ride with sobriety, and much more. An edited version of the conversation, previously published only as a podcast, is below; for the full audio of the conversation, press play below or go to iTunes or Spotify.

You’re 37. Do you feel older than your years? Younger?

I’ve been on this earth too long. [laughs] It’s been a long, rough life. But I mean, that just happens. But you don’t get to write songs the way that I write songs if you don’t, y’know, live.

But you’ve talked about that idea being a trap. It could be dangerous thinking that you got to live to provide grist for the art, right?

Well, you know, you don’t got to shoot speedballs to be able to write songs. You don’t got to be all fucked up to write songs. But one thing you have to do is take your earbuds out, get your head out of your goddamn iPhone, and pay attention to what’s going on around you and the world around you. Because otherwise, you’re going to write diary entries. And nobody wants to hear your diary entries.

Does that become more of a challenge as your life goes on, and as the world gets more full of distractions?

Well, I do think that it does get harder to find interesting things to write about amongst the public. The world is in a fucked up state right now. A lot of bad shit going on. But you really have to process what you… I was sitting at a Waffle House at one time and I heard this guy behind me tell his girlfriend, “Look, woman, if you ain’t glad I’m leaving, you ought to be.” I was like, “oooh.” And I wrote “Ain’t Glad I’m Leaving” right after that. So you know, it’s things like that.

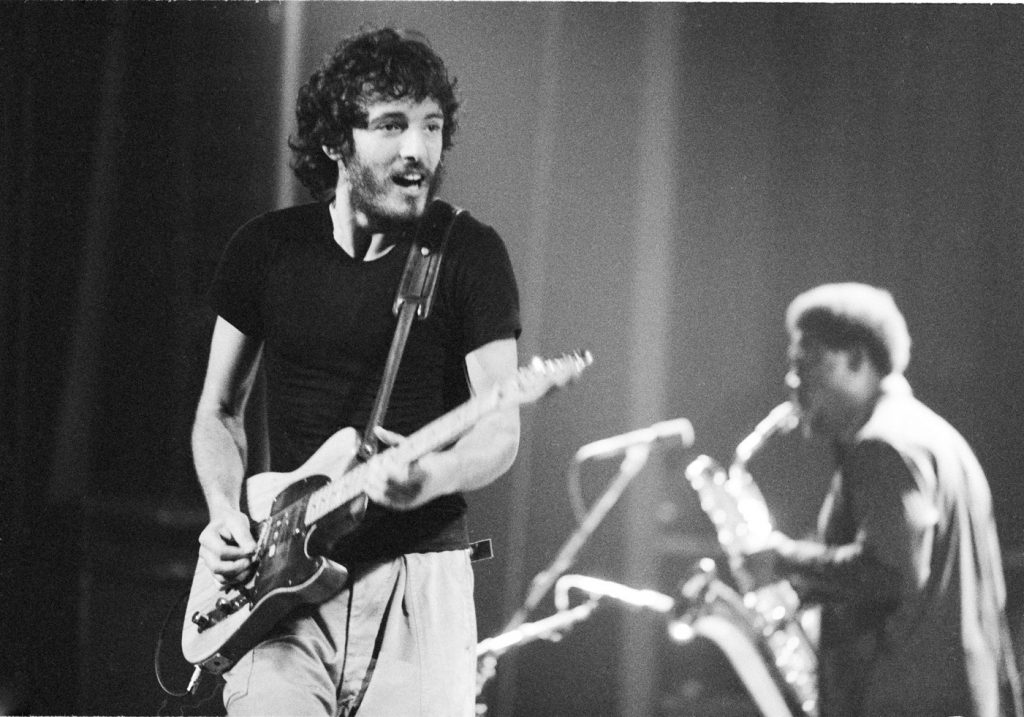

I happened to sit next to your dad at a Bruce Springsteen concert three years ago. And while Bruce was playing a song, I just happened to see Steve pull out his iPhone and start writing lyrics right there.

Yeah. I mean, I’ve always been a cocktail napkin writer. My dad’s the same way. It’s not sitting down at a desk and like, “I got to finish the song today.” It can take me six months to write a song. Because, if you stole one of my notepads, you could get a whole steno pad that just has one song and over and over and over again, edited, edited, edited, edited, edited, going over and over and over again. If you want to be a songwriter, you need to be a songwriter and nothing else matters.

There’s a lot of approaches, but just to put it on polar ends, there’s the Leonard Cohen type approach, which is “revise, revise, revise.” There’s the Neil Young approach, which is basically “first draft, best draft.” You’ve always been on the Leonard Cohen side.

I’ve always been. Most people who think that their first guess is the right guess need to keep that to shooting pool, not life and not art. Because it’s, you’re probably wrong! You’ll probably think of something better later if you give it time to rest.

You draw on a really wide range of roots music, which stretches all the way to folk and blues and ragtime. Do you see that attention to tradition and historical knowledge withering to a certain extent in the larger culture?

I do think that it is withering. Kurt Cobain was not a great songwriter because the first thing that he heard was Thin Lizzy and then he based everything off Thin Lizzy or Springsteen. He was a great songwriter because he went all the way back to Lead Belly. He understood Woody Guthrie. He understood Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Songwriting has such a history. If you get to do this for a living, you owe something to the past. You know, and you got to be ballsy to step up and write a song like “They Killed John Henry,” or “Same Old Stagolee,” but it is your responsibility to carry on those traditions if you’re going to use them.

You arguably don’t hear much connection to the real roots in a lot of modern country music…

That awful bro-country bullshit that’s coming out of Nashville now… I mean, even hip hop drives me insane now, I mean, what happened to flow? But you know this, this happens to all forms of music. I mean, if you sat next to Howlin’ Wolf right now and asked him what he thought about the state of the blues, he’d say, “ain’t no blues.” He wouldn’t be happy about it. You ever heard his quote about Eric Clapton? They said, “what do you think about all these British blues prodigies?” He goes,”I tell you, what Eric Clapton can do is you can take that whee-wah pedal and throw it in the creek on his way down to the barbershop.” Wee-wah pedal! [Wolf seems to have actually said something like this to guitarist Pete Cosey, who recalled, “I had an Afro hairstyle at the time and he said, ‘Yeah boy, you need to go get a haircut, and while you’re on your way to the barber shop, take that bow-wow pedal of yours and throw it in the lake.’”]

The story of the guy in your song “Appalachian Nightmare” parallels your own life somewhat.

A bit. Yeah. I mean, I lived in Appalachia. I saw [issues with] pharmaceuticals in the 90s. I mean, long before people started trying to sue drug companies because people are addicted to Oxycontin. That’s not drug companies’ problem. It’s our problem.

Hmm. I mean, it does sound like they were pushing doctors to prescribe and all that kind of thing.

Well, I mean, they got something to sell, don’t they? They got something to sell. But it ain’t a drug company’s problem that somebody started taking pills. You know what the problem is? Is something hurt inside them. Something wasn’t right inside them. And the world didn’t treat them right. They never felt comfortable. And they found something that made them comfortable. I mean, I remember the first time I shot heroin. I was 12 years old, and nothing had ever felt right in my life. But when that plunger went down, it was like a warm blanket wrapped over me. Everything was ok. It got un-ok, really fast. That first time, that’s the bitch. But we do have to realize, people who have drug problems are missing something inside them.

Does having a kid of your own to start to give you a new perspective on how dark this all was? I mean, 12 years old.

Well, you know, nothing will ever change the heart that’s inside of me. And you know, it goes way deeper than my father. I was a kid. I was abandoned. I was molested. I was beaten. You know, so, everybody’s lucky I’m not a serial killer. And so there’s something that will always be missing inside of me. But I will protect my daughter. I will protect my daughter and make sure that that does not happen her. I’ll do the best I can to do that. I hope she has a better life than I did.

Yeah. Well, your life’s not over yet. You know what I mean? You’re still writing the story.

Yeah, you know, it’s still going, it’s still going on. I mean, I hope she has a better youth than I did. That’s the thing.

You told me the last time we spoke that you’ve talked to a “few headshrinkers.” Is it too romantic to imagine that your art is a healing thing as well?

Writing songs and performing – if I didn’t do that, I mean, I would be insane. Not to mention it’s the only way I know how to make money other than selling dope. So if I didn’t do this, then I’d be in prison or dead right now. And so there’s something very therapeutic about it. I love being onstage, love writing songs, all those things. But once again, you can’t write songs that are diary entries. Nobody wants to hear that – even “Mama’s Eyes,” songs like that. That’s not a diary entry. I left a lot open for what other people want to think.

“Mama’s Eyes” is essentially about seeing your mother in you and seeing that as a redemption from whatever you don’t like about what you inherited from your dad, right?

Absolutely. It’s the idea of somebody who’s exactly like their father which was the last thing they wanted to be. You didn’t want to end up doing all the things that your daddy did. And you did. And your last saving grace is everything about you is like your father except for one night, very depressed, you light a cigarette and you see in the mirror that your eyes are shaped like your mother’s and that’s the only thing you’ve got that feels redeeming.

Have you ever discussed that song, or another one about your dad, “Farther From Me,” with your father?

No, no, we don’t really talk about those. The first time he heard “Mama’s Eyes,” he was standing like the proud father on the edge of the Ryman Auditorium stage years ago, and I played it solo. I remember walking offstage and he goes, ”Mama’s Eyes,’ that’s a good song.’”

You toured with Lilly Hiatt, the very talented singer/songwriter who happens to be John Hiatt’s daughter. Love it or hate it, is there some genetic component to songwriting talent?

No, no, no, because I mean, there’s plenty of sons and daughters that are the shittiest songwriters you’ve ever seen in your life. Most of them are! Because they’re trying to live up to something. And they sound too much like their parents. One thing I love about Lilly, even growing up with her dad, she has a sound like nothing else. These weird cadences. She’s great. We didn’t ride Daddy’s coattails into this business. We created something for ourselves. Our daddies can’t do what we do. We can’t do what our daddies do.

I really got to know my dad when I was like 12 or so, somewhere around there. I grew up with my mother in a shitty rundown apartment on food stamps. You know what makes the best grilled cheese sandwich in the world? Government cheese in that brown box. Best grilled cheese you ever had. SO people are like, ‘Oh, what was it like growing up with…” and I’m like, I didn’t grow up with my dad. I grew up with my mom. That’s why I wrote “Mama’s Eyes,” not “Daddy’s Eyes.”

Did he really fire you from his band at one point?

Yeah, I cost $10,000 worth of damage to a hotel room in Berlin.. I’m still banned from Millennium hotels worldwide. Because I was junked out back then. We were in Berlin and I got on the train outside our hotel and went up to this spot where I knew to cop dope, got high and got off at the wrong stop coming back. And in this open air market, I bought a jar of clown-red Manic Panic hair dye. I went back to my hotel. And I don’t remember doing this. But you know, Millennium hotels, they’re all white. The floors are white, carpets white. The walls are white. Everything’s white. I woke up in the morning, laying on the floor naked. I stood up and saw red handprints, footprints, all over. All over the room. All over the walls. All over everything. And I was just like, “What the fuck? What’s happened?” I thought it was blood. And what I done was I evidently put the hair dye in and got high, nodded out and didn’t rinse it out.

What year was that?

Must have been about 2000.

So it took a while after that to get to your first album.

Yeah, yeah, eight years. Yeah, I almost made a record for Lost Highway when I was 18 years old. It was right around the same time that all this shit happened. But actually the same A&R person that signed me to New West decided not to sign me up because I was too fucked up. She liked the songs but she was like, “we already got Ryan Adams…” [laughs]

Around 2011 you had a pretty dramatic relapse. What’s the sobriety ride been like for you since then?

It’s bumpy… But sobriety to me means I don’t shoot heroin and cocaine together.

You smoke weed, right?

A lot of weed. Uh huh. A lot. A quarter ounce a day. I like spliffs. 15 to 18 of them a day.

Do you have anyone warning you that that’s bad for someone who has a history of addiction?

My dad’s one of them. I was like, you do you. I’ll do me.

Can you write high? Does it help you?

Um, I’m not sure if it does, but it’s just one of those things when I sit and write I smoke. I mean, I don’t think there’s any substance that helps people write songs. I’m an ADHD kid. So you know, a little speed focuses your brain up, but it doesn’t mean that it helps you.

You said you were doing some prose writing, correct?

I’m working on a book called Baseball, Blues and LSD – Cultural Revolutions in America. I think about what would America be like if we never had baseball, never got the blues. Never had LSD.

Were psychedelics ever part of your drug intake?

Well, actually, I do take a lot of LSD.

You do?

Oh fuck yeah. Okay, but I got real shit, Owsley acid. Not some shit that you get from your cousin. You know? Nobody knows what that’s like. It’s a very different thing.

Your music is definitely not conventionally psychedelic.

Fuck no. I’m not a fucking hippie!

Do you have any weakness for the Dead or Phish?

I never liked Phish. I’ve never got into that shit. I was really good friends with John Perry Barlow who wrote a lot of Dead songs. I do like Workingman’s Dead. The rest of it is a lot of wandering spindly shit. Garcia was incredibly talented. I think Pigpen was incredibly talented. Some of Jerry Garcia’s bluegrass was awesome.

You’ve talked a lot of times about Nirvana Unplugged leading you to Lead Belly, but what was your journey dig into roots music from there?

I mean, a total obsession with Lead Belly that I then ended up from there, discovering Woody Guthrie, and then went back to Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Son House… I mean, this was like when I was 1213, you know, right around there. I put the guitar pick down and started playing with my fingers, I didn’t care about electric guitars. Started playing an acoustic. I think by the time I was 14, I learned to play “The So Different Blues” by Mance Lipscomb. That’s a pretty complicated ragtime song.

Did anyone teach you?

My dad showed it to me. And he was like, “you’re not gonna be able to do that.” I was like, “just show it to me.” And he showed me. And I was just obsessed.

This is the mid ’90s. So this had very little to do with anything that was going on in the larger culture.

But you know, also, I’m white trash from Tennessee. I listened to punk rock, metal and hip-hop, I listened to all that [roots] stuff when I was away from my friends, because they hated it.

I could very easily see you fronting a band like Social Distortion.

It’s like, I can see it, but I’m more interested in like, I want to make a jazz record. I want to do a record with the Preservation Hall Band. Justin Townes sings the best of Billie Holiday with the Preservation Hall Band.

That sounds fantastic.

We just got to talk the record label into paying for it. And them into doing it.