Justin Townes Earle’s Perpetual Search for Forgiveness

Before the dusty down-and-out protagonist is ready to give up on life in “Yuma,” one of Justin Townes Earle’s earliest songs, he calls his mom. “There ain’t nothing I fear,” he tells her, “so much as being alone.” Released in 2007, ”Yuma” is astonishing in its emotional tenderness, a song ostensibly about a young man who decides to kill himself that is actually a meditation on what it means to accept someone else’s pain. As he calls home to beg for forgiveness for what he’s about to do, Earle is asking listeners to grant the character the same grace.

Justin Townes Earle, who died last week at 38 of a suspected drug overdose, knew something about forgiveness. He sang about it, in nearly all his greatest songs, like someone who spent much of his life asking for it himself.

From “Yuma” to his final album, 2019’s The Saint of Lost Causes, Earle’s music was preoccupied with repentance and absolution. A former addict who would struggle with relapse on and off throughout his adult life, Earle wrote songs that refused to moralize his fellow miscreants. Those songs, like 2008’s “Who Am I to Say,” in which a narrator spends three minutes letting a woman off the hook for her transgressions, were like prayers — as if Earle were hoping that if he practiced enough radical forgiveness in his art, someone might eventually forgive him too.

Although his royal Nashville pedigree and dark backstory always threatened to overshadow his own music — it’s impossible to fully escape the shadow of Steve Earle — Earle left behind a profound body of work far more emotionally complex and nuanced than the singer’s hard-living troubadour veneer would suggest.

That veneer was built on old-fashioned country and blues tropes about mischievous wandering and unavoidable sin, and it gave Earle a layer of protection in both his records and onstage. For Earle, the romanticized American past of Hank Williams, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Woody Guthrie was a veil as much as it was his sole inspiration and creative lifeblood. But he was always too much of an empathetic songwriter, gifted with an uncanny sensitivity for familial drama and lapsing salvation, to be limited by the archetypes he inherited.

“I haven’t swayed from Bruce Springsteen’s formula of girls, cars and sex,” he joked onstage in 2009, before adding an important clarifier: “and momma.”

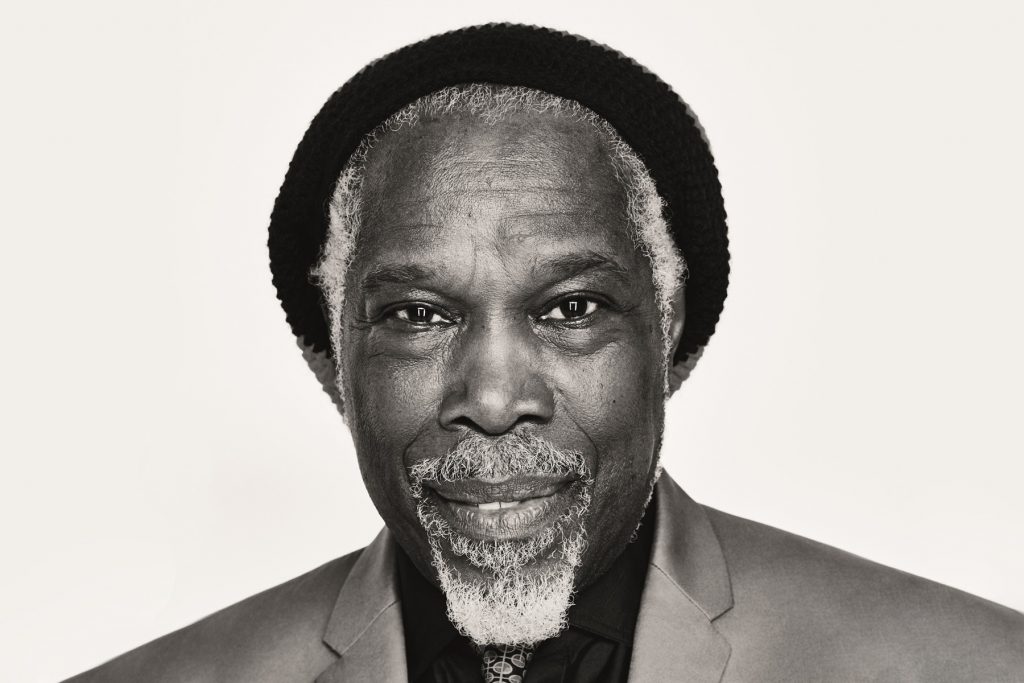

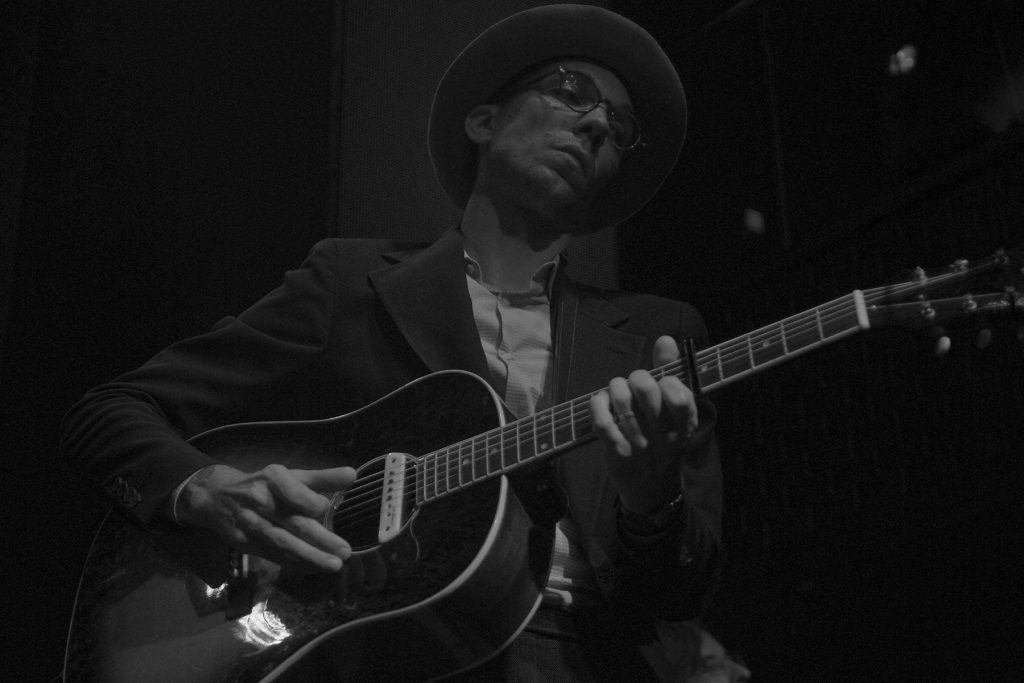

When performing live, Earle was a lightning bolt. He’d hunch his six-foot-six frame, often draped in a dapper suit, over the microphone stand, looking as if he walked directly out of a 1940s Ernest Tubb honky-tonk, shouting and storming his way through songs that sounded as out-of-time as his appearance. He was always “staring or glaring,” as Rob Miller, the head of his first label, Bloodshot Records, put it, “at something off in the middle distance.”

Earle’s onstage non-narrative mannerisms — the intensity of his fixed stare; the way he prowled the stage as he finger-picked between verses; how he’d tag a whining, high-lonesome babe to the end of a line, as if the word were a comma — often ended up telling his songs’ stories as much as the lyrics did. So, too, did the songs Earle chose to cover: the Replacements’ “Can’t Hardly Wait,” John Prine’s “Far From Me,” Lightnin’ Hopkins’ “My Starter Won’t Start,” which he delivered with an intensity he sometimes couldn’t stand to bear in his own music.

Earle, whose middle name was given in honor of his dad’s difficult, depressive friend, Townes Van Zandt, never stopped wrestling with his cursed country-music namesake. His dark inheritance (both his father and Van Zandt struggled mightily with substance abuse) was the burden he forever struggled to lay down. When he did find those bright moments of release, as in 2009’s breakthrough “Mama’s Eyes,” they tended to come as revelations. More often, though, he wrote songs about men and women who were always warning those around them that their burdens might just get the best of them — that nothing was going to change the way we feel about them now.

If Earle’s characters weren’t warning each other preemptively about what they were about to do (“Won’t Be the Last Time”), they were apologizing for their misdeeds just after the fact (“Someday I’ll Be Forgiven for This”). On 2010’s “Slippin’ and Slidin,’” Earle turned the promise of Little Richard’s riotous 1956 rocker into a sorrowful self-scold: “I shoulda learned better,” he sings, assuming the character in the midst of a relapse that he himself would suffer through the very month the song was released.

That song was on 2010’s Harlem River Blues, an album full of thoroughly modern folk originals about subway conductors, cramped city apartments, and dirty rivers, that seemed as if it would cement Earle as roots music’s next-big-thing. But any such title was likely abhorrent to Earle, who despised contemporary country music and seemed not to care much more for the increasingly popular Americana scene he was inadvertently helping foster. Instead, he remained steadfastly committed to preserving the finger-picking legacy of blues singers like Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb.

That stubbornness resulted in a series of records (2014’s Single Mothers, 2015’s Absent Father) that could be seen as something of a step back. But even when Earle risked coasting on his retro stylings, he found room to preach his radical repentance. On 2015’s “When the One You Love Loses Faith,” he delivers the sad-sack life lesson with the regretful weariness of someone for whom such a misfortune has become an all-too regular occurrence.

Earle was well aware of his stubbornness, going as far as to name his final album The Saint of Lost Causes. The record was a return to form for the songwriter, full of the type of topical originals (about contaminated water, gentrification, and bleary-eyed Memphis mornings) that had become the songwriter’s calling card at the beginning of the decade.

But it’s the album’s penultimate song, “Ahi Esta Mi Nina” (loosely translated as “there’s my girl”), where Earle would reveal, for the last time, his most shining self. The song chronicles yet another difficult conversation between parent and child, much like the phone call to mom in “Yuma.” But this time, it’s the parent pleading for forgiveness: A wayward father is speaking with his estranged daughter after years of abandonment.

“I’ll just say, ‘I’m sorry,’” he tells her toward the end of the song, “But I know it’s not as simple as that.”

By that point, it’s not clear if the daughter is even physically present for the conversation, that the father hasn’t imagined this entire exchange in his head. But Earle knows that is beside the point. By apologizing, the father can keep moving, even if all he’s done is forgive himself.