Killer Mike and 2 Chainz Tell Politicians: Stop F-cking With Atlanta’s Clubs

When Michael Render — a.k.a. Killer Mike of Run the Jewels — attended an Atlanta City Council meeting last month, he wasn’t interested in performing for the crowd. Instead, he wanted to vent his frustrations. The 47-year-old rapper, like many of the meeting’s attendees, felt like he was being used.

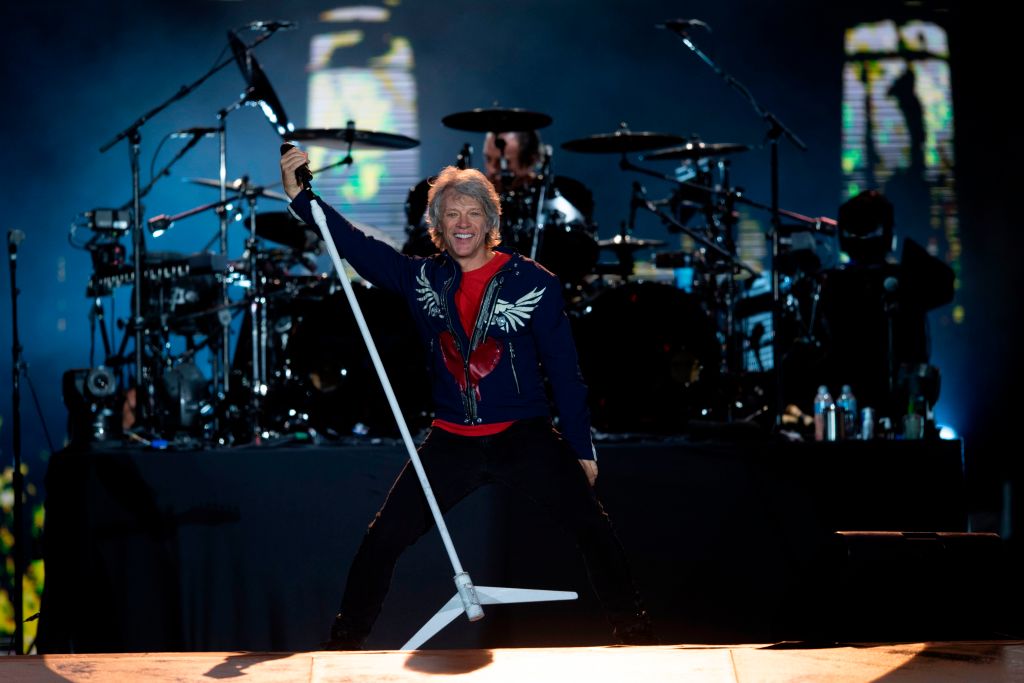

“When you come around and you need donations, when you come around and you need votes, you come to us singers and dancers and club owners and we oblige you,” he said, with Tauheed Epps — the rapper 2 Chainz — standing beside him. “This is one of the only cities where entertainers and athletes have gone on to form a business class.”

“When you go to New York, the clubs ain’t owned by people who look like you,” he added. “When you go to Miami, you might get turned away by people who look like you that don’t feel like you deserve to be in the club.” There are few industries in Atlanta, anywhere really, where Black owners can control their own destiny. Atlanta’s club scene is one of them. Or so it seems.

City leaders have proposed a change to Atlanta’s nuisance property laws, which would make it easier for municipal judges to shut down a business after acts of violence. The changes themselves are fairly incremental; a half-dozen bars and restaurants have been shuttered over the past year under existing ordinances. Most of the properties targeted by the city for enforcement over street shootouts are gas stations, apartment complexes, and corner stores with indifferent out-of-state owners.

But Render and Epps, who both own businesses on Atlanta’s lively Edgewood Avenue, weren’t there to debate the finer points of the legislation. They were drawing a line in the sand. Black entrepreneurs running small businesses created the Atlanta music scene. The city attacks them at its peril.

Atlanta’s party scene has huge opportunities coming. Atlanta will host part of the World Cup in 2026. Newly elected mayor Andre Dickens is angling for Atlanta to host the 2024 Democratic National Convention. Music is part of that pitch, in much the same way Atlanta has become attractive to aspiring musicians everywhere.

“I’ll say that a lot of musicians have a tremendous amount of value in the city as they continue to push out culture and help employ people on those things,” Dickens told IndieLand. “I got a great relationship with them. I’ll tell you that they actually on the mic, they say one thing, but in various other places, they also say, you know, ‘We want to make sure that crime stops.’ They don’t want their car windows broken out, their businesses burglarized.… So, a lot of times the conversation is multifaceted when I’m talking to them.”

But violence has been a growing problem on the Atlanta streets and within the city’s music industry. Atlanta’s homicide rate spiked during the pandemic, with the fourth-highest increase of large cities. Atlanta has more violence per capita than Chicago today. That violence has disproportionately emanated from club beefs and feuds among aspiring rappers. And many of the most high-profile incidents have taken place downtown, in the heart of the city’s tourist district.

“Someone is going to have a nightlife in a convention city. It’s going to be the owners of Hard Rock … or it’s going to be the little people who went to Frederick Douglass and Mays and Southwest DeKalb [high schools]. The question is going to become ‘Are we going to keep Atlanta a place where people can grow and thrive?’”

For example, the Georgia Aquarium is across the street from the former location of Encore Lounge, a hookah bar on Luckie Street that had 171 emergency calls to police over two years. One shooting managed to put a hole in the dolphin tank.

“Once you shoot at the dolphin tank, all bets are off,” said Dustin Hillis, an Atlanta city councilman who chairs the public safety committee. The city was eventually able to get the lounge permanently closed, after more than a year of litigation. “I want everyone to go to enjoy nightlife. However, I want them to be able to return to their house at night and not have to worry about, you know, ‘Am I gonna get shot by a stray bullet for some beef by some other people that I don’t even know?’”

The law as it stands right now allows for the city to start going after a business after even a single incident of violence. The new legislation is intended to clarify the process, better define what constitutes a qualifying act of violence, and explain what steps a property owner can take to keep a place from being declared a public nuisance.

Between a push for more aggressive enforcement of nuisance laws and the prosecution of high-profile rappers like Young Thug and Gunna, the leaders of Atlanta’s music industry and club scene say they’re feeling some pressure right now.

“There is a sense of urgency … because it’s like, ‘Hey, well, how far does this go?’” said Korey Felder, a club and restaurant owner who sits on the city’s nightlife advisory council. “We’re not thinking, ‘Hey, we’re just getting attacked.’ We feel like the entire infrastructure is getting attacked. And if we don’t put our foot down, we will get this Atlanta gold taken away from us.”

The fear of Felder and others in the industry here is that nightclubs — generally small businesses with local owners — will be forced to spend more money than they can afford on security requirements created by the city’s legislation. Those businesses will then fold and be replaced by national chains like the glitzy, touristy Margaritaville restaurant and hotel that opened across from Centennial Olympic Park in July. Black ownership in a city that advertises itself as a place for Black entrepreneurs will give way to white guys from New York and L.A., especially with the explosive redevelopment of downtown and midtown Atlanta that’s fueling gentrification and expansion.

“As Atlanta grows, corporations are going to be coming in here,” Render told the council. “Someone is going to have a nightlife in a convention city. It’s going to be the owners of Hard Rock … or it’s going to be the little people who went to Frederick Douglass and Mays and Southwest DeKalb [high schools]. The question is going to become ‘Are we going to keep Atlanta a place where people can grow and thrive?’”

Hip-hop dominates the charts, and Atlanta dominates the genre. But there’s no equivalent to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium for country music in Atlanta’s rap scene. Instead, the music wafts down Metropolitan Avenue out of Chargers and Challengers, handcrafted in nondescript studios and delivered one club at a time. The closest match to the Grand Old Opry is Magic City, the famed strip club at the grotty end of south downtown.

“Magic City has been here a long time,” said Michael Barney, Magic City’s founder. The strip club has been the stomping grounds for celebrities for decades, from Deion Sanders to Lil Baby. Stacey Abrams made it a campaign stop. But more than one shooting started with an argument at the club, including one tied to the YSL gang case.

There’s only so much a club catering to visitors can do to control its clientele, Barney said. “We can’t control the people who come to our establishment. We open the doors for everyone,” he said. “Here we are risking our lives to tell them to stop. You’re putting the pressure on us.”