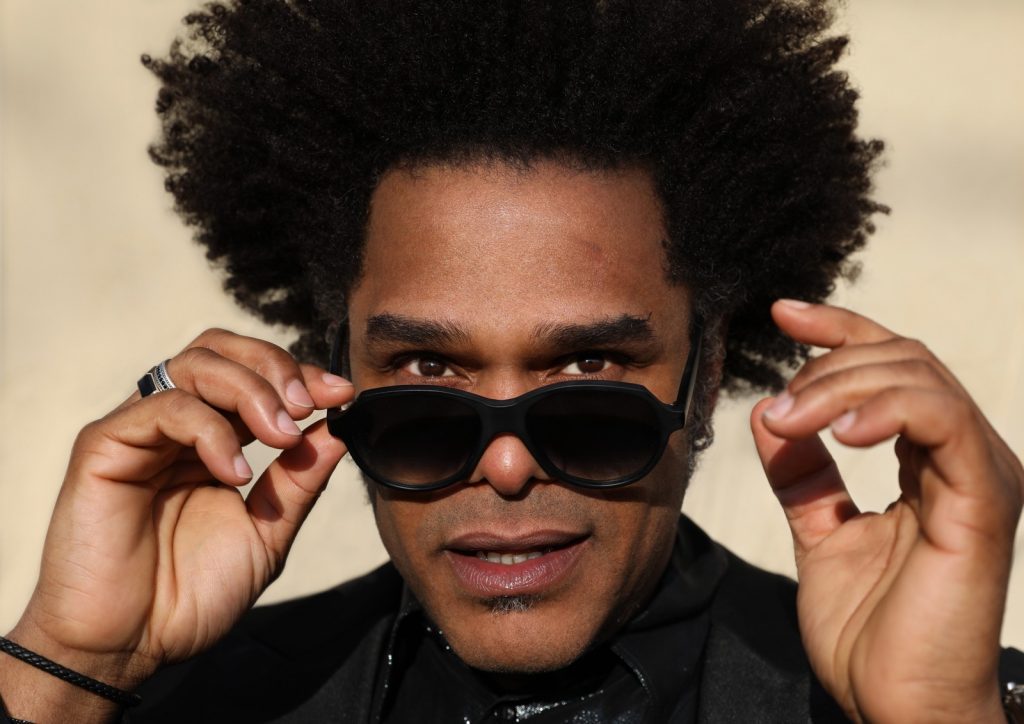

Maxwell Wasn’t Sure He Wanted to Be a Star. ‘Urban Hang Suite’ Left Him No Choice

In the early 1990s, Stuart Matthewman, the writer, producer, and multi-instrumentalist known for his work in Sade, heard a remarkable demo: a ballad that stretched out over nearly seven minutes, making room for daredevil falsetto and a bass line as elegant as a spiral staircase, building to a description of a sexual liaison so ecstatic that it lasts for days and eventually brings police to the door.

“A guy from the record company said, ‘It’s from a new artist, would you meet him?’” Matthewman recalls. “I was like, ‘It’s amazing, but it sounds like it’s already done.’” Not long after, Karl Van Den Bossche, a percussionist who also worked with Sade, came through New York to do sessions with the young man behind the demo: A then-unknown Brooklyn native named Maxwell. When Van Den Bossche stopped by to visit Matthewman later, he brought the singer as well.

The two men ended up working together on multiple tracks that appeared on Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite, the singer’s debut, which turns 25 this week; Maxwell is honoring the birthday with a reissue and a performance at the NAACP Image Awards. His most vital album, Urban Hang Suite helped prove that a pre–hip-hop R&B tradition could still be creatively and commercially viable at a time when rap was already taking over popular culture.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

While Urban Hang Suite is dashing and assured, its creator was profoundly ambivalent about his place in the music industry at the time. In the early Nineties, a young Maxwell was enraptured by Marvin Gaye, Prince, Graham Central Station, and the “warmth” of studios with Neve mixing consoles, but he wasn’t sure he wanted to be a singer. “I was peddling music around as a songwriter,” Maxwell recalls. “I wasn’t so sure that I really wanted to be in the front. I saw in the media how people are mocked and destroyed — I didn’t have that kind of thick skin.”

He also worried that he wasn’t supposed to make the type of R&B he loved. “Having a mom from Haiti and a father from Puerto Rico, being from Brooklyn and not the South, I felt like, did I deserve to be part of this tradition?” Maxwell says. “That would come up a lot inside of myself and of course from people when I was trying to do what I was trying to do.”

The fact that Maxwell felt like an outsider may have made it easier for him to turn away from the dominant mode of the time. The early-Nineties airwaves were packed with fusions of rap and R&B: the whiplash-inducing pleasures of New Jack Swing, followed by sample-driven hip-hop soul, which made cross-genre collaborations commonplace. But “everything was very programmed-sounding,” Matthewman explains. “What we were doing was programmed, but it sounded live because we allowed other instruments to breathe and play around the vocals. No one was doing crazy smooth-jazz solos.”

Maxwell assembled an unusual group of musicians: not just Matthewman, who recalls that the singer “was very enamored with the Sade album Love Deluxe” at the time, but also Leon Ware — the singer-songwriter-producer, who, in one of the most outrageous acts of generosity in music history, donated a planned 1975 solo album to Marvin Gaye, resulting in the singer’s I Want You LP — and Wah Wah Watson, a guitarist whose résumé included Gaye’s Let’s Get It On and Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall.

“I was a 22-year-old kid flying to meet guys who were 50, 60 years old,” Maxwell says. “For all intents and purposes, they thought the industry was done with them. I was walking in like, ‘I think you’re incredibly valid.’”

Those were just a few elements of what the singer describes as a “smorgasbord of cultures” flowing into Urban Hang Suite. Maxwell collaborated for the first time with guitarist Hod David, who co-wrote three songs and has worked with the singer ever since. Maxwell enlisted other pros with enviable track records as well: David Gamson, a former member of Scritti Politti who had also produced for Chaka Khan and Sheila E.; Mike Pela, who produced and engineered for Sade and Fine Young Cannibals; and Itaal Shur, who would go on to mint money by co-writing Santana’s gargantuan hit “Smooth.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

The first half of Urban Hang Suite is springy and suave. It opens with “The Urban Theme,” a vocal-less funk workout that bleeds wah-wah guitar; the track is reprised later on the album in slightly different form, a trick that Gaye used twice on I Want You. The record label found the idea of starting an album in this way baffling. The lead A&R “was like, ‘What’s the deal with the instrumental?’” Maxwell recalls. “I was like, ‘That’s the point — it starts with an instrumental and ends with a slow version of the same instrumental.’”

Maxwell follows that intro with four gently danceable cuts, including the Ware co-write “Sumthin’ Sumthin’” — originally titled “Hot Chocolate,” the track has the album’s most aggressive bass line, whipping and wriggling and popping — and the single “Ascension (Don’t Ever Wonder),” co-written by Shur and originally titled “XXX.”

“Ascension” sold more than a million copies, and it’s not hard to understand its allure: There’s the gliding economy of the groove, which seems to walk on water; the reckless falsetto run from Maxwell that opens the song; the strangely sticky lyrical construction of the hook, which swings from questioning to emphatic (“Shouldn’t I realize/You’re the highest of high/If you don’t know, then I’ll say it/So don’t ever wonder”); the subtle tumble of drums that precedes the chorus every so often. Maxwell then caps the first half of Urban Hang Suite with the demo that entranced Matthewman, “…Til the Cops Come Knockin’,” which had originally been written by Hod David with a bass line that reminded the singer of Motown great James Jamerson.

The second half of Urban Hang Suite is more subdued, a series of Quiet Storm ballads. “Whenever Wherever Whatever,” a drum-less Matthewman co-write that sets Maxwell against tense acoustic guitar, is the set’s most blatant Sade homage. “We loved it; it was so simple,” Matthewman remembers. “A guy from the record company came in and said, ‘It’s really beautiful, have you got drums coming in?’” (No.) While “Whenever Wherever Whatever” is another demonstration of Maxwell’s dexterity in the upper register, “Suitelady (The Proposal Jam)” has more hoarse bite, along with a rhythmic slink not unlike what Prince was playing with around the same time.

In the years since Urban Hang Suite was released, it’s frequently been name-checked, along with D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar (1995) and Erykah Badu’s Baduizm (1997), as a foundational album for the neo-soul movement. But those two albums are really separate endeavors; Maxwell’s music is airier and often more dance-floor friendly, pushing past the 95 b.p.m. mark into a region where Brown Sugar never went, and that Baduizm only flirted with.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

In addition, the bass-heavy rhythmic engine for D’Angelo and Badu was hip-hop — both their debuts were co-produced in parts by Bob Power, who helped mix and engineer A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory. (The Roots also helped out extensively on Baduizm.) Urban Hang Suite is really just soul, with a lineage that reaches back to Keni Burke’s “Risin’ to the Top,” Sade’s “Haunt Me,” the English group Loose Ends — “we both loved their mix of drum machines and live stuff,” Matthewman says — and Shuggie Otis, among others.

When Maxwell completed the album, it sat unreleased for nearly a year. (“I’ve experienced that before with Sade when they’re scared of putting things out,” Matthewman says sympathetically. “They sat on the first album for a long time before they put it out in America.”) “I was in a studio apartment with one window that faced a brick wall,” Maxwell remembers. “I had my little cassette of this album which had been mixed and mastered by Tom Coyne, who has passed away since, a genius mastering guy. I just sat and waited.”

Some of his ambivalence about his path remained even when Urban Hang Suite finally hit stores in April 1996. “I wanted the cover to not be my face,” Maxwell says. “That seems like a marketing ploy that’s obvious in today’s world, but I was actually scared that something would happen. I wanted it to happen, but I was secretly afraid.”

“Then ‘Ascension’ came out,” he adds, “and the whole lack-of-visibility part didn’t really work.”