Music’s Road Crews Are Overwhelmingly White and Male. Meet the People Trying to Change That

By the time he signed on for Justin Bieber’s Believe tour in 2012, Lance “K.C.” Jackson had more than 30 years under his belt as a stage manager and touring pro; he’d worked with Prince, Destiny’s Child, Luther Vandross, and Earth, Wind, and Fire, among others. Now, on a tour headlined by a white artist, he drew quizzical looks backstage whenever he went to help Bieber with a harness that allowed him to descend onto the stage sporting wings. “There aren’t a lot of black props workers out there, so people were looking at me like, ‘Who is this guy? Can he make it happen?’” Jackson recalls. “It was a prejudgment.”

While anecdotal, Jackson’s story was revealing. Anyone who’s been backstage at a concert or on the road with a music act will have noticed two things about the employees scurrying around to prepare the stage and venue: Most are doing difficult, back-breaking work that’s vital to live shows, and most are white and male. In a recent Pollstar/Venues Now survey of 1,350 live-music professionals, 67 percent were male and 85 percent were white. Black workers constituted only two percent, with Hispanic workers at 3.6, and two percent deemed “multiracial/multiethnic.” “There’s been some progress, but not enough,” says Tony Bulluck, currently Earth, Wind, and Fire’s production manager. “A lot of times, I walk into buildings and people make assumptions that I’m the janitor or with security.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

But as part of the reckoning in both in the entertainment business and the world at large, the diversity spotlight is now shining on road crews and others working on that side of the music industry: the people who set up lights, sound, and the stage for shows, and even handle backstage catering. Jackson is the co-founder of Roadies of Color United, launched in 2009 and devoted to connecting people-of-color crew employees to share stories and job news. And this past spring, Fitz and the Tantrums co-lead singer Noelle Scaggs, who was also becoming aware of this disparity, took it upon herself to launch Diversify the Stage, dedicated to spreading awareness about this issue and educating both music professionals and those who want to enter that side of the business. Diversify the Stage is particularly setting its sights on BIPOC, LGBTQ, and “female-identifying and gender-nonconforming” individuals.

Scaggs admits that the minuscule number of minority crew members didn’t immediately occur to her. In the early indie-soul days of Fitz and the Tantrums, the sight of largely white crew members at shows that themselves drew a largely white crowd seemed normal. “Coming from the alternative space, I honestly just figured that’s just the way things were because of the genre, where the audiences are predominantly white,” she says. “But then I realized it wasn’t just in the alternative space but in pop. The bigger the artist, you start to see the lack of diversity in those spaces as well.”

In the music industry as a whole, diversity remains an issue. In a recent survey of industry workers conducted by the Creative Independent site and musician and activist René Kladzyk, most agreed that “more than three-quarters of their company’s leadership positions were held by white people,” and nearly 70 percent reported that “more than three-quarters of their company’s leadership positions were held by cisgender men.” A Spotify-funded study published earlier this year by USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative determined that only one in five recording artists were female, and only one in 37 producers are women. The USC group is currently working with Universal Music to research, in their words, “the extent to which men and women of color are excluded from music’s leadership ranks,” although results haven’t yet been announced.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

In that context, many agree that the time has come to address the small number of people of color (and women) in the live-concert business. “Absolutely it needs to be addressed,” adds James Bell, another longtime rigger. “For the better part of five or more years, I was the only African American doing rigging. As time went on, a few more women came in the business, and a few more people of color, but the ratio is still horrible.”

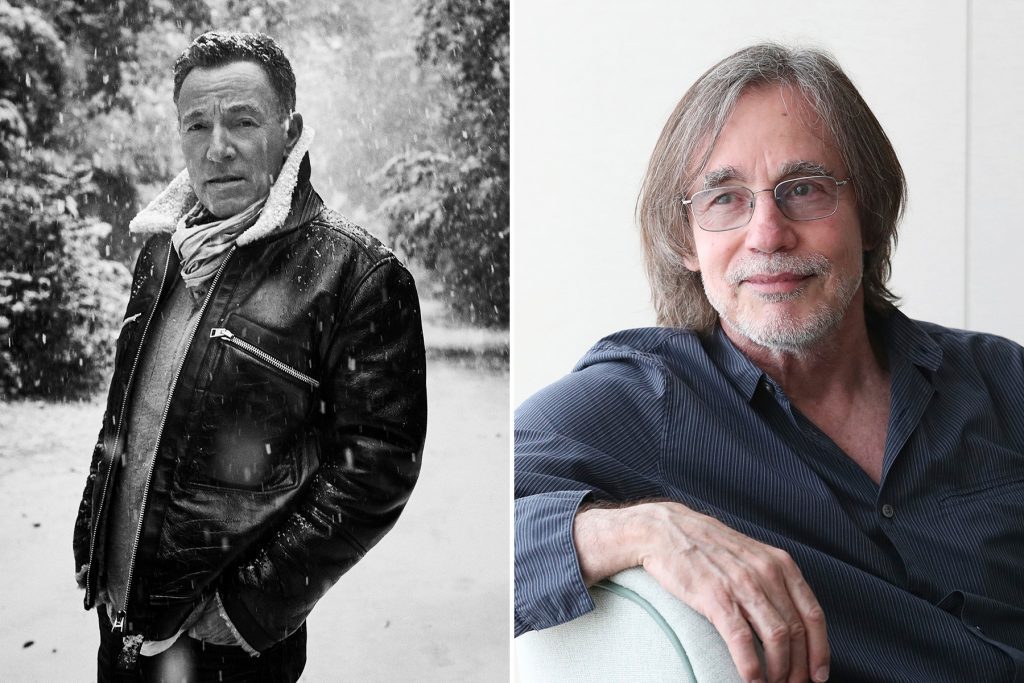

K.C. Jackson, Stuart Gray, Victor Reed Sr., David “5-1” Norman, Lisa Pittman Dennis, Shae Usher, Bill Reeves, and Ronnie Stephenson (from left) of the Roadies of Color United 10th Anniversary Planning Committee

Courtesy of Lance K.C. Jackson

“When George Floyd happened, everyone’s awareness went through the roof,” says Gerald McDougald, known early in his career as the “hip-hop rigger” for his work hoisting and installing sound systems at rap shows. “And from there, it went to, ‘Hey, we deserve to work these shows.’”

Although more women are part of road crews than ever, often working in production and wardrobe, their numbers also remain small. Jeneen Anderson, who’s been Soul Asylum’s tour manager for the past six years, saw for herself when her band recently went on the road with two other like-minded groups. “It started with me and two other women,” she says. “And halfway through the tour, one of the women left. So it was me and another woman out of 50 or 60 people. It was us and a lot of dudes.”

Exactly how many people of color and women work those jobs — or are available to work them — is still undetermined; no databases or directories exist for any of these jobs. That was the motivation behind Roadies of Color United when it was launched more than a decade ago. Jackson and co-founder Bill Reeves (a veteran tour and production manager who’s worked with Prince, Anita Baker, Luther Vandross, D’Angelo, and, currently, Anthony Hamilton) had the idea when they were perusing an earlier road-crew social network and noticed some glaring omissions. “For every 100 faces, there would be one person of color, maybe one female,” Jackson says. “We thought maybe we should start our own social network. People say, ‘We’d love to hire more people of color if we knew where to find them.’ We said, ‘Well, maybe we can create a directory of our membership.’”

As those who work with hip-hop and R&B acts attest, the crews for those artists tend to be more diverse. McDougald cites recent tours with Dr. Dre and Eminem for its inclusive employees. Shae Usher, who has toured as a production coordinator or assistant with Lil Wayne, OutKast, Chris Brown, and Nicki Minaj, says, “We had black and white workers; some of our carpenters were white.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

According to those on the other side of the stage, though, pop, rock, and country tend to have the most largely Caucasian workers. For the past 25 years, McDougald has toured with acts both in pop (Britney Spears, Fall Out Boy, Jonas Brothers) and hip-hop (Jay-Z, Lil Wayne, P-Diddy). Along the way, he’s noticed firsthand the difference in crews, especially during one tour with a leading hard-rock band. “I went around the world with them for nine months, and I never saw another person of color,” he says of their crew. “They treated me with respect, but I had to say, ‘I’m going to the hood so I can see some of my people.’”

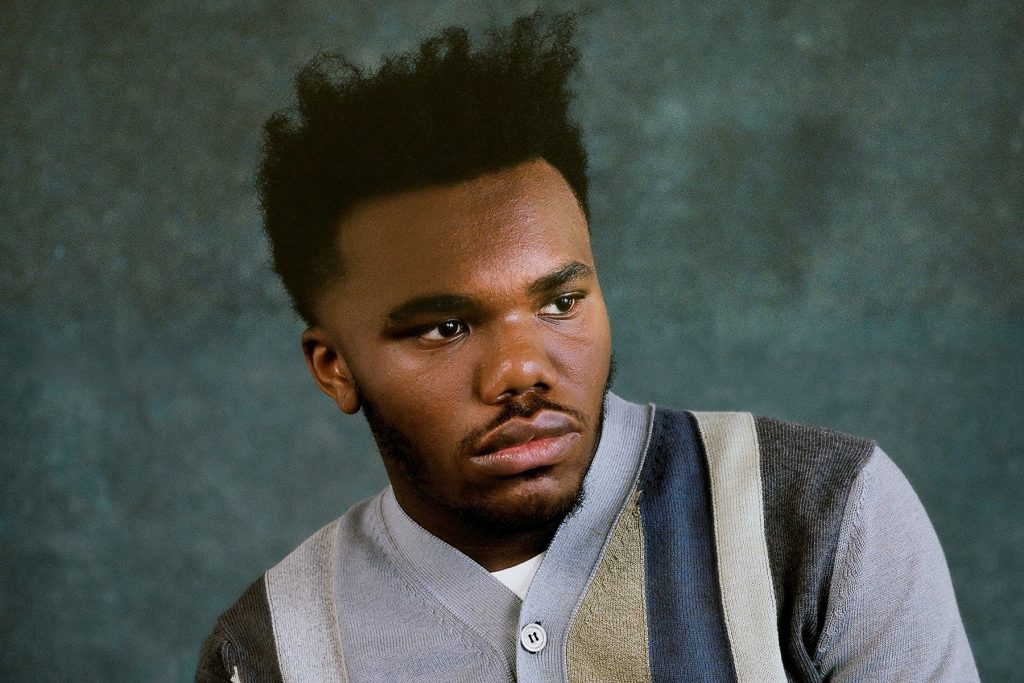

Gerald McDougald at work

Courtesy of Gerald McDougald

Despite his own extensive résumé, Roadies of Color United’s Reeves says he’s never been approached about running a rock tour. “You would think someone who has competency in that area should be able to work across genres,” he says. “Rock & roll doesn’t care what amp it plays through. But I’ve never been offered or asked about joining a pop or rock tour. I can name eight or 10 white guys who are production managers on R&B shows. I can name two black touring managers who work pop and rock.” (One of them is Jerome Crooks, the esteemed tour manager for Tool.)

Many in the business ascribe that situation less to any form of racism and more to familiarity: When big tours start cranking up (which, hopefully, some will do next year), tour managers tend to reach out to the same crew members they’ve worked with over time, knowing they’ll get the job done in situations filled with technical and logistical challenges. “Most artists are very loyal to their crew,” says veteran tour manager Marty Hom (Fleetwood Mac, Stevie Nicks, Barbra Streisand), who is himself Asian American. “There’s not a huge turnover either. If you, as a crew member, go out with an act, you pretty much stay with that act unless you do something horribly wrong and get fired.”

“It’s not because they don’t want us,” says McDougald, who has recently done rigging work for Kendrick Lamar and RuPaul. “It’s because they don’t know us. Big-time production managers just know their core group they work with.” Adds Jackson, “No one is doing this on purpose. It’s systematic. It’s a game of musical chairs, with not enough seats when the music stops. And most of the time they call the same people, so the seats are already taken before the music starts playing.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Still, some in the business detect a bias based on a combination of race and genre. “For years, it was seen as a given fact that black [crew] guys couldn’t do pop because they weren’t as competent,” says Reeves. “The thinking was that you didn’t have to be as good an audio or lighting guy or rigger because the standards were somehow less or looser than in rock and pop.” Adds Bulluck, “Some guys haven’t said this, but some of them don’t consider roadies or techs of color competent. They don’t know them from the man on the moon. It’s a matter of trust, and I understand that. When you kick off a show, you want to feel safe and secure and that everyone is doing the best job they can. But to make the assumption that they have to be Caucasian? That’s not happening.”

Scaggs, who herself is black, admits that her band could do a better job of rounding out its own team. On Fitz and the Tantrums’ first tour, more than a decade ago, she was the only woman until a female assistant was eventually hired, and she realizes their team needs more people of color. “Where we lack is on cultural diversity,” she says, “and that’s attributed to a lack of people of color applying for jobs when our tour manager puts out the word. They may be hired based on experience of working with a band similar to ours. But we’re working on it.”

Others, though, express disappointment that some major hip-hop artists graduate from largely black to predominantly white crews once they reach superstar status (and often switch management or road crews in the process). And as Scaggs and others say, such hiring matters are sometimes out of the hands of artists, who rarely interact with crews and may not even see much of them. “There are so many variables to getting a crew hired,” says Scaggs. “You have production suppliers bring in staff as well, for catering or wardrobe, and if their staff isn’t diverse, it doesn’t matter what your own team looks like.”

Jeneen Anderson at work

Courtesy of Jeneen Anderson

Even when a woman lands a top road job, she can still be viewed with a degree of skepticism — as Jeneen Anderson has learned when Soul Asylum’s tour bus has rolled into some buildings for a show. “I get off the bus and walk into a venue and people would assume that I’m doing merch or was dating someone on the bus,” she says. “Even when I walked onstage, people assume you don’t know what you’re doing or say, ‘Let me help you carry that piece of gear.’ Which is very nice, but I don’t need help. Sometimes it’s hard to tell a 50-year-old man what to do when you’re half his age. I get a lot of, ‘I’ve been doing this for 30 years, sister.’”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Whether it’s people of color, women, or LGBTQ workers, the hiring issues also stem from that absence of any sort of directory of these workers along with the word-of-mouth nature of many of these jobs. “These are not jobs you apply for,” says Reeves. “The way it works is, someone calls and says, ‘So-and-so is looking for a tour manager — are you interested or available?’ It’s not like a job listed in the want ads: ‘Wanted: production manager for major artist.’”

“Wider knowledge is the problem,” Shae Usher concurs. “There’s a lot more women who should apply for these positions, but they may not know about them.”

Due to that situation, Roadies of Color United as well as Diversify the Stage are currently at work reaching out to BIPOC and women employees in their business to compile an extensive, fact-checked database. Working with Never Famous, an online job portal created by Crooks, Diversify the Stage is hoping to give young and college-age candidates opportunities to network and find jobs in the concert business. To further enhance its own organization, Roadies of Color United held its first awards ceremony early this year, and Diversify the Stage has been endorsed by tour managers for Coldplay and Pink, and agents at prominent companies like ICM and WME.

“Consistently, the thing I get back from tour and production managers now is, ‘You know, it never occurred to me that my crew was always white — I didn’t have a bias against hiring black crew members, it just never came up,’” says Reeves (who believes the percentage of black crew workers is closer to eight to 10 percent, not the two percent cited by the Pollstar/Venues Now survey). “Now I’m hearing, ‘Now that I think about it, the next time I’ll at least consider diversifying my crew.’ I’ve been told that by at least a few production managers.”

“What we say is, ‘I can wrap this cable as fast as you can, and I can push boxes as fast as you can,’” Jackson adds. “‘Don’t look at my color — look what I can do.’”