Operation Ivy’s ‘Energy’: Inside the Making of a Ska-Punk Classic

Operation Ivy only existed for two years, from May 1987 through May 1989, but in that time, the Berkeley, California, band forever altered the future of both punk and ska. They weren’t the first to mix these genres, but the band — made up of singer Jesse Michaels, drummer Dave Mello, and future Rancid members Tim “Lint” Armstrong and Matt “McCall” Freeman, on guitar and bass, respectively — completely changed the rules for what was possible in each, inspiring thousands of others to follow their lead.

The band didn’t exist in a vacuum: The late-Eighties East Bay punk scene they sprung from was fertile ground for creativity. At the heart of it was 924 Gilman St., an all-ages, all-volunteer-run venue that held its first show on December 31st, 1986. Founder Tim Yohannan, who also launched influential zine Maximum Rocknroll, envisioned it as a space that would challenge all the norms of a capitalist nightclub. It was the perfect breeding ground for Operation Ivy’s innovative genre blend. In this excerpt from In Defense of Ska — a book from ska drummer turned journalist Aaron Carnes, which mixes essays, interviews, and memoir-style deep dives into the often-maligned genre, and will be released May 4th — he charts the formation of Op Ivy, as well as the recording of their first (and only) album, Energy, before their untimely breakup.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Gutter-Punks, Goths, and Anarchists

Basic Radio was not a traditional ska band, or even trying to emulate the 2 Tone Records sound in any way. The group, whose members included Tim Armstrong and Matt Freeman, played rock, punk, and hip-hop, but used ska as its glue. “This diversity of influences was typical of bands in those days because Berkeley in the early Eighties was a real melting pot of musical cultures and different types of kids,” says Jesse Michaels. One of Basic Radio’s final shows was in Dave Mello’s tiny garage in Albany, California; they got a feeling for how well their breed of jumbled-up ska would go over within the small community of East Bay punk rockers.

When Basic Radio broke up, Armstrong wanted to form a strictly punk rock group. He invited Freeman, Michaels, and Mello. Armstrong envisioned Operation Ivy to be somewhere between East Bay punk band Crimpshrine, early Social Distortion, and the Clash. In the first few practices, those elements came together well. However, ska also seeped in, but with the same hyper energy as their punk songs. “Once we started playing, the ska influences quickly emerged because of Tim’s familiarity and natural talent with that type of music, and because the ska songs we wrote sounded good,” says Michaels.

Once Operation Ivy was playing ska, Armstrong gave the rest of the group a crash course in the music. “I had never really played ska,” says Mello. “I remember Tim saying, you got to listen to these records: The Specials, Madness, English Beat, and the Selecter. He just said those four records.” At their heart, the members of Operation Ivy were punk rockers, even when they were playing upbeats. Operation Ivy only rehearsed for a few months before they played their first show in Mello’s garage, along with Crimpshrine, Bitch Fight, and Isocracy, which was jammed packed with friends and other bands. The crowd surrounded the band tight enough that they could literally touch the musicians as they played. The energy was so punk rock the wooden shelving unit on the garage wall nearly fell on Mello mid-set, but a few audience members caught it in the nick of time.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

The next day, the group played its second show at the recently opened Gilman where they opened for MDC. Gilman was a natural fit for Operation Ivy. Initially, Tim Yohannan ran Gilman somewhere between a socialist collective and a community center with a whole network of people sharing duties. Outcasts from every subculture flocked to Gilman: Goths, gutter-punks, skaters, art students, anarchists — all rebels against the status quo. Creative kids formed friendships and took care of the venue, even volunteering to do menial tasks like sweeping the floors and taking out the trash. Bands weren’t listed on flyers, in newspaper ads, or even on the venue itself. You would show up and find out what was going on that night.

Sometimes bands didn’t even play, in which case, kids just hung out. There was hardly a line separating the band from the audience. Anyone could hop on stage and sing another band’s songs. Musicians were interchangeable or ambidextrous, spontaneously joining and leaving other groups. Unlike emerging punk scenes in other cities, these bands were wildly diverse. Pre-Gilman, most of these kids didn’t know each other and had developed their own styles. Gilman brought them all together. The environment supported originality and creative thinking. Even Gilman’s famously posted wall rules (no racism, no sexism, etc.), were thoroughly debated from the beginning by its volunteers as to how strictly they should be enforced.

At Gilman, no one watching Op Ivy told them they were playing ska wrong. Had Operation Ivy tried to join the mid-Eighties ska scene, they would have been laughed off the stage. The Uptones, the Bay Area’s first ska band — formed in 1982 — may have had punk energy, but they didn’t play punk songs. You couldn’t be a ska band that dressed like dirty punks, played sloppy upbeats, and fell off the stage mid-song, accidentally unplugging your guitar cable. Likewise, Operation Ivy would have never fit in the hardcore scene a few years earlier where dogma demolished outliers. At Gilman in the late Eighties, with the small crew of kids that brought this scene to life, the very notion of punk rock was being redefined. What everyone did was punk; it wasn’t defined by how the music sounded. Operation Ivy’s adventurous approach to melding late-Eighties East Bay punk with ska came at just the right moment. East Bay musician and local punk promoter Kamala Lyn Parks explains this liberating spirit at Gilman: “It was the attitude, the energy, the political bent, challenging the norms — you were part of it.”

In this landscape, a diverse, free-spirited group of East Bay punk bands all cropped up together that said fuck you to punk-rock dogma. There was the metal adjacent Neurosis, a confrontational, funny feminist rap trio called the Yeastie Girlz, the light-hearted pop of Sweet Baby Jesus. There was the Beatnigs, an all-black industrial-punk group who banged on metal objects. And within all of that, there was a single group playing ska songs: Operation Ivy, who all these bands loved dearly.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Mysterious Hybrid

Punks in other cities got a taste of Gilman in 1987 when Maximum Rocknroll made its first attempt to document these bands with a two–seven-inch record compilation called Turn It Around! Local engineer Kevin Army recorded most of the bands in two short sessions, one band after another. Later Army would record several seminal punk albums from bands like Jawbreaker, the Mr. T Experience, and Green Day, but at the time he wasn’t familiar with this current crop of bands. He was the only engineer in the area Maximum Rocknroll could find that wasn’t scared of recording punks. Once he started the Turn It Around! session, he recognized immediately the thread connecting all these musically diverse punk bands: They were all great pop songwriters.

‘In Defense of Ska’ is out May 5th. For the cover, author Aaron Carnes and photographer Cam Evans painted a wall of the legendary venue 924 Gilman (with the owners’ permission). “[It was] an all day process,” says Carnes.

Book cover photo by Cam Evans

Army was especially impressed with Operation Ivy. They were a sloppy, raw punk band throwing ska riffs into their songs. Their politically charged anti-cop anthem “Officer” was unlike anything he’d ever heard. “It’s this mysterious hybrid. It’s simultaneously ska, hardcore, and pop-punk,” says Army. “It’s melodic and catchy.”

The kind of ska Operation Ivy played was totally new territory. It went way beyond having punk elements. That was already happening. The Mighty Mighty Bosstones had released hardcore- and metal-influenced ska, but the Bosstones still adhered to ska traditions. They wore suits, they had a horn section, and played as tight and in-tune as possible. The N.Y. Citizens, though much less famous, formed in the mid-Eighties and were also very untraditional and punky in their approach. “We had this ‘fuck the world’ approach to everything. A lot of our stuff didn’t come out very ska. We would meld it all together,” says N.Y. Citizens bassist Paul Gil. They too didn’t stray from the core mission of being a dance band. Some Op Ivy songs were power-chord punk blasters; others were upbeat-driven ska songs. But it wasn’t a dance party. It was unleashed, unapologetic punk-rock fury. “We never really played ska shows; only punk shows,” says Michaels. “Some ska people distinctly didn’t like us because we had no horns or suits and I was too much of a spaz for them.” Op Ivy was doing something no band before them dared: recontextualizing ska within the punk genre.

Other cities around the country had growing underground punk scenes, many with great bands and killer DIY venues, or at least local promoters that could navigate through the halls and basements to sustain a scene. Parks soon discovered this. She may have been instrumental in opening Gilman — she and Victor Hayden identified the building as a perfect all ages venue for Yohannan — but she didn’t heavily participate once it got going. She wanted something of her own. With Gilman providing a stable place for East Bay punk bands, she transferred her energy to helping bands book elsewhere. San Francisco punk band Clown Alley, who she unofficially managed, asked if she would book them some West Coast dates. With a little research, she spotted DIY scenes up and down the coast. The tour went splendidly. The drummer then asked Parks how she booked shows so he could do the same for his other band, Sacrilege B.C. She gave him her contacts, figuring this would be her final time booking a tour.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Larry Livermore, co-founder of Lookout Records, heard what Parks had done for Clown Alley and asked if she would get Operation Ivy on the road. He had just released the group’s debut EP Hectic at the beginning of 1988 and they were itching to tour. That was an easy yes. She loved that band and was friends with all the members. Operation Ivy became the first Lookout band to hit the road.

The tour was six weeks across the country in a beat-up 1969 Chrysler Newport. Leading up to the tour, they’d spent the prior year playing every weekend, usually at Gilman or other DIY spaces in the region. Their whole life revolved around Operation Ivy. “We had a routine where we would make stickers and we would do this thing called dohing where we would stick them on people’s backs and stick them on cars and walls, wherever we would go,” says Mello. “We talked about our band as much as we could. We were always at Gilman Street.”

The shows Parks booked were mostly punk rock DIY shows that she located through copious research. The audiences ranged from five to a couple hundred people, though usually it was in the 50 to 100 range. In Chicago, Op Ivy played a big show with Screeching Weasel and headliner Zero Boys, who were reuniting.

Operation Ivy had developed in the unusual bubble that was Gilman, but word was spreading in the deepest punk rock circles about them from their two tracks on the Turn It Around! comp and their Hectic EP. Most of these people they played to on that tour had never seen a punk band play ska, but they took to it right away. “Even though ska and punk were different, they still knew ska. They listened to the Descendents, they listened to SoCal punk, they listened to the Specials,” Mello says. “It wasn’t like we were blowing people’s minds. We were just playing something that they were like, ‘Of course those things mix together.’ ”

Mistakes Are OK

That first Operation Ivy tour had a big impact on the band’s sound. It pushed them in a more ska direction, a natural evolution that grew from playing every night to new crowds. If there was a down moment in the sets, they’d start to play a ska or reggae jam to fill the silence. Mello and Freeman were locking in on their grooves better every time. Armstrong would inevitably hop in with a skanking guitar and get it going. If Michaels was feeling it, he might start improvising lyrics or pull out words from a song like Journey’s “Lights.” The audience would go crazy. The consistently positive response they got from audiences gave them the confidence to slow down some of their ska and let it actually have more of a dance feel. They wrote “Unity” on tour and started working out ideas for what would be “Sound System” and “Take Warning.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

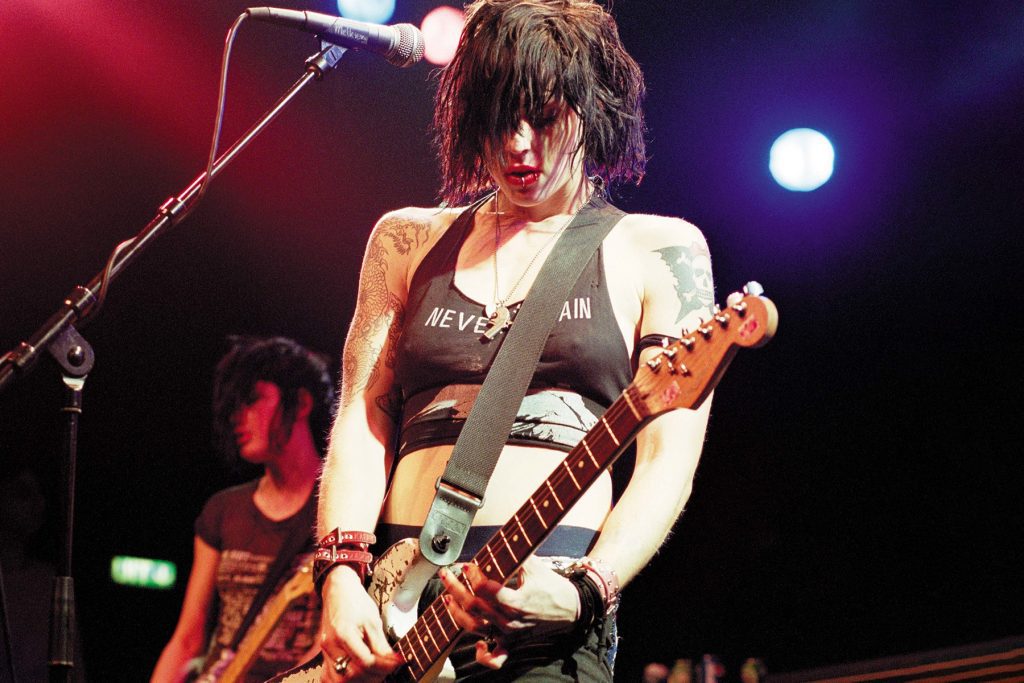

Operation Ivy performs at 924 Gilman in 1988.

Murray Bowles

When the band returned home, they already had material for a full-length, but it took a while to record. Gilman sound guy Radley Hirsch had a vision for the recording, and the band were willing to follow him on it. He started by recording demos at Gilman. He then recorded the band’s instrumental takes at a nearby empty warehouse and did a bunch of overdubs at his apartment basement in San Francisco. It took a while to get what he was hoping to get. He nitpicked parts of it, like the snare drum sound. He overdubbed Mello playing just the snare parts in his bathroom because they weren’t popping in the warehouse recordings. Regardless, the whole recording wasn’t sounding right to the band. “It was too hollow of a sound,” says Mello. “We didn’t hear the actual instruments. It was too much noise, too much bleed. He wanted us to feel like this is going to be a great thing, but it was taking so long, we just got bored of the whole process.”

They went back to the man that captured them so well on the Turn It Around! tracks and the Hectic EP: Kevin Army. The objective was to get it done and not dawdle around. They had spent so much time trying to record what would be their first album, Energy, in the warehouse that they’d already updated their song “Freeze Up” to say that it was 1989, instead of 1988. Army recorded the basic tracks at [San Francisco studio] Sound and Vision in a single eight-hour session in early 1989. Fortunately, they’d been practicing the songs for nearly a year, so it wasn’t tough. Army got solid, immediate takes. He focused on capturing the band’s live sound, and making sure you could hear the quality of that pop songwriting he spotted when he first fell in love with the group during the Turn It Around! recordings.

Every song was recorded in one or two takes, no more. “I had seen them play live. I knew, don’t fuck that up. Don’t make them freaked out and uncomfortable. You throw up the mics as quick as possible and you get them to play,” says Army. “Mistakes are okay. Chuck Berry records are filled with them. Music business people are over-focused on perfection. Later I would be laughed out of an A&R office for my demo tape when it came to the Op Ivy song. People would fast forward or laugh.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

He positioned the members in a semi-circle, facing each other inside the tiny space at Sound and Vision. The drums sat in front of the door, which was left open so the sound would bounce around and create natural reverb. Overdubs were minimal, though guitarist Tim Armstrong did some “scrape” guitar overdubs, some leads, and some random rhythm parts to give the songs dynamics. And that saxophone in “Bad Town” was overdubbed by a friend of the band, Paul Bany, who was the guitarist for Mello’s old band Distorted Truth. Michaels was so focused and thoughtful when he sang, he’d rewrite lyrics in the studio.

Army mostly kept his comments to a minimum. The band was almost perfect on their own. But he interceded during vocal overdubs when the band pushed to add gang “oi oi oi” vocals on every single song. “Left to his own devices, Tim will do that,” Army says. “I went, ‘You guys are starting to sound like the Village People.’ I deliberately used ‘The Village People’ to bother them.” It worked. They eased up on the gang vocals. Army told them to think about the magic that happened when it was just Michaels and Armstrong’s vocals going back and forth.

Mixing went quickly. Army adjusted the levels of reverb, bass, and treble differently on every track. “If it’s a 10-song album, you can blaze through it with all the songs sounding the same. But I think if it’s that many songs, you want to mix it up.” Army captured the band exactly as they were: Raw, fast, loose and with Armstrong’s almost grating, dissonant tone. Michaels’ lyrics were political but also intellectual, thoughtful and personally relatable. He railed against the oppressive, corrupt system, but made you think about your own role in perpetuating its power, and how you felt about that. “He was always writing lyrics. He was always trying to stress different syllables and come up with different words or different lines,” Mello says. “Jesse would think about what he wanted to say, what the song meant and just rework the way he wanted to sing it. And it would come out more meaningful.” Several songs started with a chorus hook that Armstrong or the group would make up, usually something that spontaneously came to them that they thought sounded cool. Michaels would pore over what he could say in the verses to give it meaning. “We came up with ‘I got no nothing in mind,’ ” Mello says. “Jesse would sit there and think about the meaning of that and what he could say about an empty generation, about not knowing and trying to make my way in this world but not saying anything meaningful.” Few punk or ska vocalists since have come out with lyrics as universally relatable as what Michaels wrote for Op Ivy as a teenager.

Heartbreaking on Every Level

Ever since Op Ivy had gotten back from tour, they were getting buzz in the larger punk community. They’d started as part of Gilman’s scene; now they were a draw unto themselves. The group had a European tour scheduled for the summer of 1989 to coincide with the release of Energy. They would tour alongside U.K. ska-punk band Culture Shock. But before Op Ivy left for tour, they broke up due to interpersonal conflicts and an inability to hold together this thing that seemed to be growing bigger than they ever imagined. “One of the saddest days of my life,” Parks says. “It was heartbreaking on every level. They were a very magical band to see.”

Even with the momentum they had, Op Ivy might have been lost in obscurity forever had Lookout not released Energy. In 1989, the ska world wasn’t sold on Op Ivy. Ska label Moon Records, to whom they’d sent Energy demos to in the late Eighties, passed on the group. Tim Armstrong mentioned this to Moon owner Rob Hingley years later in 1998. Hingley told him he passed on it because he didn’t have the funds, but the reality was he wouldn’t have put it out anyway. Whatever it was this band sent them, it was not ska. It certainly didn’t fit the Moon brand of 2 Tone–influenced ska. Lookout released Energy two months after Op Ivy broke up. Even though they never toured to support Energy, it was the record for an entire generation of punk and hardcore kids. The same would be true for ska kids, but it took a while.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“We were starting to get a good reputation and good crowds,” Mello says. “It’s a shame we broke up, and [to think about] what we could have done if we would have still been together. But it doesn’t do any good to think of it that way. It’s better to think of what we did accomplish, how much fun we had, and how much we inspired people.”

As more ska bands heard Energy, it forever changed the rules of ska-punk. It set the foundation for a new way of thinking in the ska world. Fishbone had influenced nearly every Eighties ska band to broaden what styles they mixed with ska, but Op Ivy inspired bands to rethink the culture of ska itself.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Eric Din’s band the Uptones may have inspired the members of Op Ivy, but he quickly became a fan, and sees them as a distinct line in the sand for American ska. “Whatever the Uptones did, what Fishbone did, Crazy 8, all those other bands. It was a moment in time,” Din says. “Through that little funnel of Op Ivy, it just spat a thousand other bands.”

From the forthcoming book In Defense of Ska by Aaron Carnes. Copyright © 2021 by Aaron Carnes. Published by CLASH Books. Reprinted by permission. Available here.

You can listen to Aaron Carne’s accompanying podcast wherever you stream them, or here.