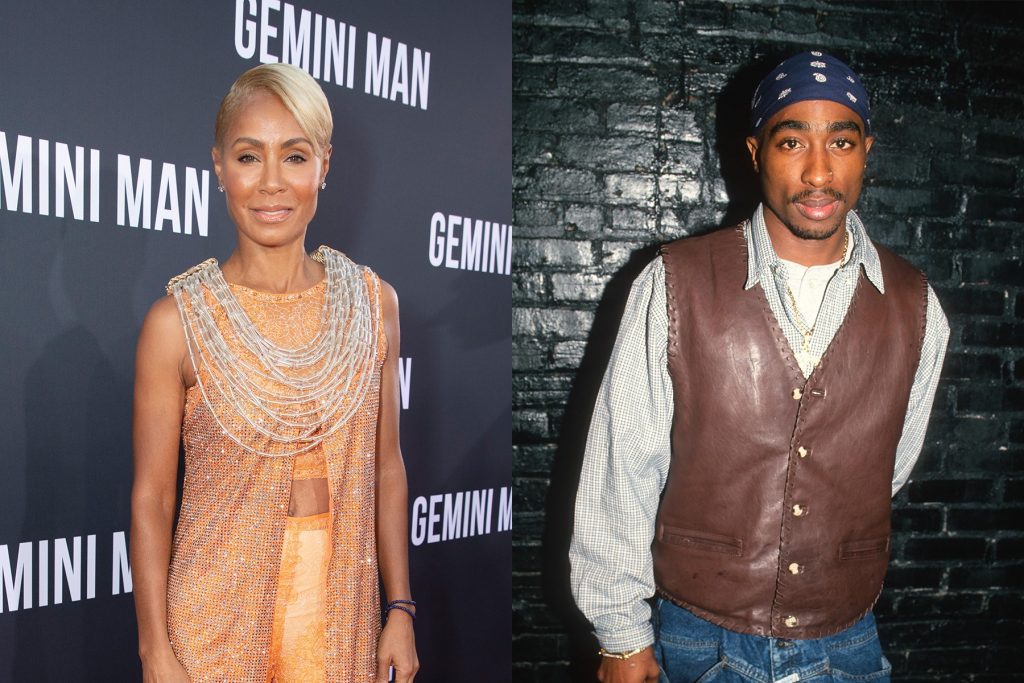

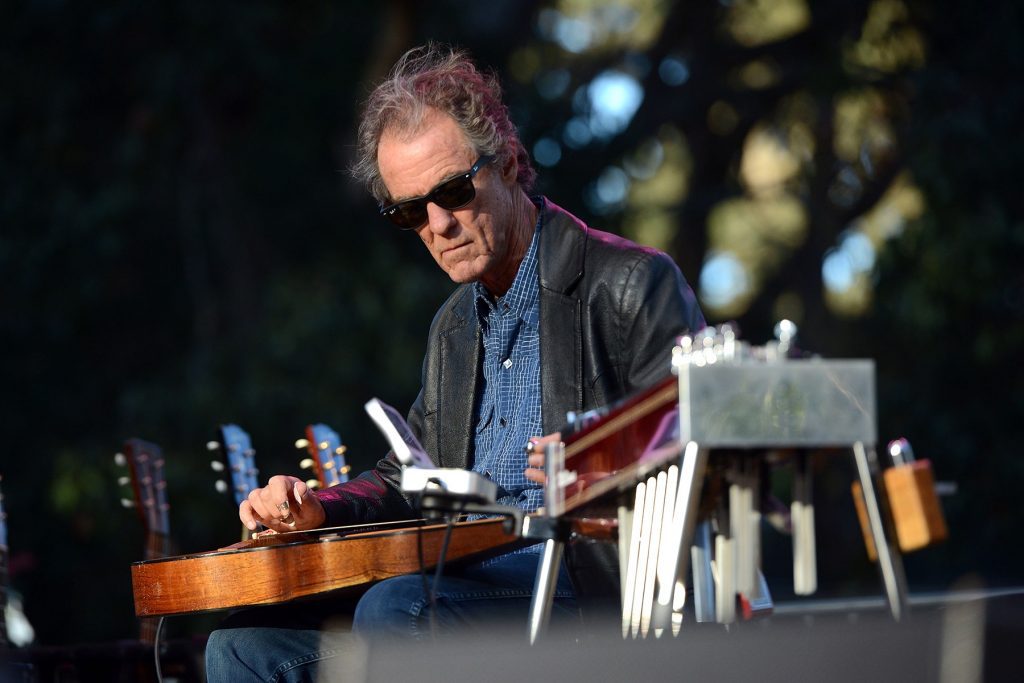

Pedal-Steel Guitarist Greg Leisz on His Years With Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton, Bruce Springsteen, and Daft Punk

IndieLand interview series Unknown Legends features long-form conversations between senior writer Andy Greene and veteran musicians who have toured and recorded alongside icons for years, if not decades. All are renowned in the business, but some are less well known to the general public. Here, these artists tell their complete stories, giving an up-close look at life on music’s A list. This edition features pedal-steel guitarist Greg Leisz.

Greg Leisz’s list of credits is so incredibly long and varied that it’s almost hard to believe it’s all the work of a single person. In 2013 alone, the pedal-steel guitarist played on records by Daft Punk, Eric Clapton, Kris Kristofferson, Glen Hansard, the Beach Boys, Bonnie Raitt, Billy Bragg, John Fogerty, and way too many others to mention here. Every one of the past 30 years has been that busy in the studio, and he’s still found time to tour with the likes of Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, Eric Clapton, K.D. Lang, and Bob Weir and Wolf Bros.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

“I don’t know how to comprehend everything I’ve done,” he says. “I recently tried to just make a list of the names of the people I’d played with, but it was so many that I had to stop. When I look at Discogs and AllMusic, I go, ‘I forgot about this record and that record …’ But for me, it’s the breadth of the stuff that I’m most proud of, not necessarily the number.”

We spent two hours on the phone with Leisz, and just barely scratched the surface of his life and career. Getting to all the great records he’s played on would have resulted in an interview longer than Infinite Jest and the uncut edition of Stephen King’s The Stand combined.

Where are you right now?

In Southern California, kind of North of L.A., near Santa Barbara.

How has your pandemic year gone?

I live in a place that’s a good place to hang out during a pandemic since it’s very close to nature. I’ve been very fortunate since all my friends and family have remained healthy and fine. And my wife and I spend a lot of time together during the pandemic since we’re both musicians. We were both planning on being on tour a lot. But it’s been a crazy year, just like it has for everybody. I feel very fortunate we got through the whole year.

I haven’t been on a plane for about 14 months or something. The last plane flight I was on, I went to New York at the beginning of last February. That’s a little odd. That’s probably the longest time I haven’t spent on a plane since I was a teenager.

Are you vaccinated?

Yeah. I’m fully vaccinated, have been for some time. I guess because of that, I’ve been fairly active. I haven’t really been hunkered down as much in the last couple of months, particularly since I’ve been vaccinated.

I want to go back here and talk about your life. Tell me your first memories of being a kid and hearing music that really reached you.

Well, that’s a good question. I have to go back pretty far. I grew up in a family where I didn’t have older brothers or sisters. Music wasn’t brought to me through older siblings or really through any older kids. Fortunately, my mother was musical, even though she sang more opera. And when she was young, she actually sang in a Broadway musical and light opera in the mid-Forties, during the war. My first musical experiences were hearing her sing around the house.

I took piano lessons when I was nine, but I didn’t have a good teacher and I gave it up pretty quickly. But once I started hearing songs on the radio I liked, I’d memorize them and play them on the piano. I got pretty good. At some point, I just picked up the guitar, probably around 1962 or 1963. I started teaching myself how to play out of these folk-music books, which basically had songs by the Kingston Trio and Burl Ives, like “On Top of Old Smokey.”

When I heard “Tom Dooley” by the Kingston Trio, that totally hit me. “Hang down your head, Tom Dooley/Poor boy, you’re bound to die.” That was like, “Wow.” And when I started playing guitar, I knew those melodies from hearing them on the radio. And then I was like, “Wow, I can actually play this stuff. I can teach myself.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Once I could actually play the guitar, I started meeting a couple of other kids in the neighborhood and we’d play together. By the next year, the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan. I already knew how to play guitar by then. The music started coming into my consciousness a lot more. I was like, “Now I have to get an electric guitar.” That was the start of the garage-band culture of the Sixties. I basically grew up inside of that.

During this time, are you thinking of music as a possible career, or is it more a fun hobby?

Well, no. I never thought of it as a career. I didn’t have any role models or anyone that would suggest that could even be a possibility. I’m not one of those people that went, “This is what I want to do with my life.” It’s weird to call it a “hobby,” but I guess that’s what my parents would have called it. I didn’t really know what to call it. It was something I really liked to do and I started doing it a lot.

What sort of career did you see yourself pursuing?

I actually didn’t think much about a career. If you think about that era, I was in the mid-Sixties conundrum generation where you had a generation gap and a draft. The idea that you were going to have to go to Vietnam and maybe kill people, it wasn’t conducive to thinking about being a musician. There was a lot of stuff in your head, so you didn’t think that was a possibility.

I went to college and took stuff that kept me out of the draft. I didn’t study music because I didn’t think that was a career option for me. I also didn’t have parents that thought it was a good idea. I basically was just playing music with my friends. And then I started working with some musicians that were playing in some of the folk clubs in Southern California. And then it became, “Wow, I can make a little money.” But I had all sorts of different day jobs the whole time.

Like what?

I sometimes just took day factory jobs in Orange County. I got a job as a janitor and as a substitute mailman for a while. As a janitor, I’d work at City Hall, just cleaning bathrooms and stuff like that. I tended to gravitate towards jobs where I didn’t have to be around a lot of people. I didn’t really like service jobs. Being a mailman was great because you had a car and you drove around and delivered mail.

I basically thought at one point that I’d be a geologist or a forest ranger or something like that. I actually went to college for a while and studied geology. But I spent a couple of summers working as a forest ranger in Idaho and fighting fires. And I’d save money from doing that and come back to California with several thousand dollars, which is a lot of money for fighting fires. And then I would live off that money and play music for as long as I could.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

By that time, I had been in some bands and the bands had broken up. You get very disillusioned about that being a possibility, but you still keep doing it. I was like, “I’m going to try and keep playing music and try to get better.” I saved up my money one summer and bought my first pedal steel and started teaching myself how to do that.

What drew you to the pedal steel?

It was the same thing that drew me to the electric guitar. It was the sound of it. When I taught myself how to play the electric guitar when I was 13, 14, it’s a visceral thing. Once you get an instrument in your hand and start playing it, you go, “Wow.” Then you teach yourself something and you’re able to do it, you can apply it, it’s mind-expanding. Once you’re in that world, your ears become really open to hearing stuff.

When I heard electric guitar on records, I wanted to play that. It really wasn’t like I saw the Beatles on TV and said, “I want to be like them.” I never really did that. I never really tried to emulate a pop star. I just liked the sound of the guitar and I wanted to do it. I wanted to figure out how to make those sounds.

The same thing happened when I heard pedal steel on records that I listened to. I was drawn, even before pedal steel, to traditional slide-guitar music. In the late Sixties when a lot of people were listening to harder rock, Led Zeppelin and things, I was listening to Jimmie Rodgers, old country music like Hank Williams, bluegrass music, and I was learning how to play that music, and I was learning with other musicians that were kind of turned on to that.

At the same time, I was heavily influenced by Bob Dylan and that type of songwriting. I was drawn to the records that I guess now we talk about as “folk-rock” or “country-rock” and I kind of got pulled into the pedal steel through that music, through hearing it on the records that I liked.

Did certain pedal-steel albums influence you?

There was a Judy Collins album called Who Knows Where the Time Goes. It has really great songs, but it had some amazing pedal steel by Buddy Emmons. I think I became really aware of his tone and his playing. I loved the stuff that Sneaky Pete Kleinow played on the Flying Burrito Brothers records that he did.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Once I got to the point where I could hang out in bars, I used to go to country bars. I’d sometimes listen to the band just to hear the pedal-steel player. They were just guys that were factory workers during the day that played country music at night. They were amazing. The sound of the guitars blew my mind. I was usually to shy to go up and talk to anybody about it, but I just kind of absorbed the music. Eventually, when I finally got one, I had friends that I could play along with. I taught myself how to play.

It sort of became an avenue to make a living by expanding my vocabulary as a guitar player. “Maybe we can have that guy in the band. We already have a guitar player.” I could see it as a smart thing to do.

To jump forward here, can you tell me about the formation of the Funky Kings?

That band was really the brainchild of this guy named Richard Stekol, who was one third of the songwriting triumvirate of that band. He basically put the band together since he was the only person that knew everyone that ended up in it. He met Jules Shear. He met Jack Tempchin. He introduced Jules to Jack and vice versa. He’s the one that knew me.

We got a record deal because of Jack Tempchin’s past of writing songs for the Eagles on their early records. He tried to get a deal as a solo artist and he was told that he should get a band around him. He was probably looking to do something at that same time. The band got signed very quickly because there was already a songwriter that had a couple hit songs. We hadn’t even learned many songs when we got our record deal, and Arista, Clive Davis, signed the band.

Long story short, we made one record. We did a short tour opening for Hall and Oates. We went in the studio to make another record and the band broke apart during the dramas of making the second record.

I’m looking at your credits and there’s a 10-year gap after the Funky Kings and before you start racking up a ton of credits. What happened in that time?

Well, in those 10 years, I spent a lot of time playing in clubs, basically. That pretty much sums it up. I went through a little bit of soul searching. I wasn’t expecting that band to break up. It wasn’t the first band that wasn’t successful that I was in, but it was the band that had the most attention focused on it, quite a bit in a very short time.

I basically felt like I had to hone my own skills. The best way for me to do that was, I felt, I needed to play music, not sit around and wait for something to happen. I met the first great drummers, the first great bass players, the first great musicians I ever played with while I was playing in country bars, rhythm & blues bars, any type of places.

Starting in 1986 or so, your credits list gets insane pretty quick.

It gets crazy. I can’t really believe it myself. I didn’t even have a business card. If someone asked me for my phone number, I’d gladly give it to them and write it on a piece of paper. They’d stick it in their wallet and maybe they’d lose it, or maybe they’d write it down.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

I started meeting people that came out of almost the punk era in the Eighties. They were all getting more into roots music. There was something called “new country.” Once that started happening, I had been pre-conditioned to play that kind of music. I had put in my time many years before that, learning that stuff. I already knew it and I came out of the Sixties and had a folkie background and could understand that stuff. It was a natural fit with a lot of people. I was able to play a lot of different kinds of music.

The early Eighties must have been rough then.

It was. I didn’t listen to contemporary music for a long time, probably from around the late Seventies until the late Eighties. I didn’t really listen to the radio. I missed that whole era. That’s what they called New Wave at the time. There was a lot of music I couldn’t really understand. I didn’t really see myself in the picture. There was a lot of questioning, to be totally honest. I think I was probably at least 40 years old before I started thinking, “Maybe I can keep doing this.”

I want to talk about a few random credits that caught my eye. Let’s start with Roxette and their hit “It Must Have Been Love.”

[Laughs] That’s so random. And it’s interesting to me that you’d think of that. Also, it’s interesting to me that it even happened at all. They are Swedish musicians, but I knew some of the same people that they did. At some point, Roxette came to town for a gig and they asked me to come into the studio and play with them. I didn’t know much about Roxette and it was just that day. They did two version of that song. I don’t think the one I play on was in Pretty Woman. [Editor’s note: Leisz does, in fact, play on the Pretty Woman version of the song.]

I love the Victoria Williams song “Crazy Mary.” You play on that.

I love that song too. That’s another very interesting one. That album [Loose] was a really great album for me. I really liked that project. I had met Victoria before that. This was a time where I met a lot of people like Victoria Williams and Lucinda Williams, Dave Alvin, Dwight Yoakam, Rosie Flores … there was a bunch of people that all kind of knew each other and were playing in the same clubs in L.A. in the late Eighties. Everybody was trying to get record deals.

Victoria had already gotten a deal and made a record in New York. She made one record before that, at least. What I remember is that was right around the time she was diagnosed with MS. Maybe it was after. I think that happened when she was on tour with Neil Young.

We recorded that song with Don Heffington on drums and Greg Cohen on bass. Victoria played guitar and I played pedal steel on it. I played a lot of different kinds of guitars on that record.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Pearl Jam have played that song countless times.

They recorded a version of it after she got MS. That was the first Sweet Relief album. Pearl Jam did “Crazy Mary” on that. I guess they could have learned it from the version we did. It was really close in time to after her record came out.

Then you were with Joni Mitchell on Turbulent Indigo in 1994.

That was the first thing I did with her. Interestingly enough, there is this thread between Victoria Williams and Joni Mitchell. Larry Klein bought me onto Turbulent Indigo. He was still married to her at that time. I think he’d become aware of my playing on a couple of other records, especially this K.D. Lang record Ingénue. He heard my pedal steel and thought that was something that Joni would embrace in her music. He’d been with her for a pretty long time.

I play on two songs [“Not to Blame” and “Borderline”] on that record. They were different sessions and I recorded with her sitting right next to me while I overdubbed. I didn’t play live with her. But I overdubbed. It was pretty terrifying.

I can imagine that being intimidating.

[Laughs] Yes, but I’m used to being intimidated by people in the music business. If you have a certain kind of shy disposition, you’re usually intimidated because you don’t know what to say and you just hope the person that is intimidating won’t be intimidating because of something that you say.

And my experience with that is, a lot of people that I’ve worked with, you think they’re going to be intimidating, but they’re so good at making you feel comfortable that you wind up singing that person’s praises.

That was the case with Joni Mitchell. I asked her if she had any ideas for the song when we started. I wanted to know where she wanted me to play. She set me straight and said, “I’m not going to tell you anything. I’m not going to try and edit what you do.”

I knew right then it was all up to me. I just had to hope she wouldn’t walk out of the room and not come back. But she was fine with it. She ended up having me play enough takes that she felt she could put together what she wanted. A few weeks later, they called me back and I did another song.

Four years later, I worked with her again on Taming the Tiger. My friend Brian Blade played drums on it. She decided she wanted to go play some live shows. At first, she thought she’d use Brian’s jazz band. Brian didn’t think that was a great idea. He felt it would be too many musicians and that it should be more stripped-down. Brian recommend to her that maybe I should do it.

Was this the 1998 tour with Bob Dylan and Van Morrison?

Yeah. It was that tour. We did a spring leg and a fall leg. On the fall leg, Van Morrison didn’t do it. But Dylan called up Dave Alvin and asked him to be the opening act. That was fun since I had done all these albums with Dave in the preceding years. I had produced a bunch of his records too. That was kind of a cool thing.

Those threads can have a huge impact on your musical journey. The people that you meet and have a connection with, suddenly there’s another connection later on. Without Brian making that suggestion, I don’t think she would have thought of it. And then seven or eight years after that, she did her last album [Shine], and she called me to work on that one, too.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

That was fascinating since I spent more time with her and got to see more process. I played on something where she hadn’t finished the lyrics yet. It was really a drag that she didn’t continue after that because she didn’t get enough … people didn’t really appreciate that last album. She got treated a little rough in the press in the reviews. She was just like, “I don’t need this anymore.”

She also never really toured again after 1998.

She did a tour with an orchestra [in 2000], but it was last time she went out and played guitar with a band.

Going back here, can you talk about playing with the Smashing Pumpkins on Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness? You’re on the James Iha track “Take Me Down.”

That’s another one of those random things. I just got contacted. I forget if it was directly by James Iha or the management. It was just that Billy Corgan was allowing James to do one song on a double album. [Laughs] He was like, “Here’s this carrot. You can do anything you want.” He asked me to come to Chicago and I was there. I overdubbed on the song. He had Flood and the other producer [Alan Moulder]. They had two different studios in the same complex. Billy was in one room working on his stuff and James was in this other room working on his song. It wasn’t much.

Later, I did play on a James Iha solo album [Let It Come Down] that Jim Scott produced. I went back to Chicago and worked on that with James. Another funny story is that when we were in the studio, he had a banjo. I didn’t have one and said I’d like to play it. A couple of months later, a box came to my house and it had a banjo in it. It didn’t say who it was from. He basically gave me a banjo. I learned how to play it and I’ve now played it on a couple of records. It’s kind of funny.

You’re on Beck’s song “Sissyneck” from Odelay.

Yeah. That was the first time I worked with him. I ended up working on a few other albums with him. Odelay was interesting because he was working with the Dust Brothers. And it was the first time I remember going to somebody’s house to record. It was just basically recorded in a bedroom. Up until that time, it seemed like there was always some kind of a studio you worked in.

I hadn’t met Beck before that. And it was a cool thing to get to do that. I never ended up doing anything live with him. But I have worked on several other sessions with him, including several where we played live in the studio, like Mutations.

You’re on Paula Cole’s “I Don’t Want to Wait,” which was an enormous song.

That was enormous, yeah. I was also on “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone,” which was pretty big too. Playing on that record was a big deal to me. Prior to that record, I knew who she was. I had seen her play live when she opened for Sarah McLachlan in Los Angeles. She was on my radar as somebody up-and-coming.

This was her second record and she wanted to make a bunch of changes. She was unhappy with her producer and had lost her guitar player because I think it was her boyfriend and they had broken up. She decided she wanted to take over the production of the record herself. I don’t think Warner Bros. was particularly happy, but they allowed her to do it. To make a long story short, I knew her engineer and he asked me to come play on the record.

I was basically asked to play all the guitars on the album. We met the day I got the studio. She was very focused, so it was great working with her. She had a strong vision. She wanted a wah-wah on this guitar part and something atmospheric elsewhere. She wanted something very specific. On the other hand, she was always very interested in hearing what I could come up with.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

It was very quick. Her budget had been stretched by the time, so she wanted to work fast. I overdubbed all those parts. She had already done all her drum parts and vocals and most of the bass. She didn’t want a lot of guitar parts. She wanted something focused on every song. I really had no idea it would become what it became.

I don’t think the label was very confident. They were like, “She’s gone off the tracks, she fired her producer.” I think they were surprised. It was one of those things where she had a breakout song with that “Cowboys” song and suddenly the record company was like, “Oh, we knew it the whole time!” I’ve seen this a lot before.

And so she goes through this whole process where she has these hits and she makes another record and it didn’t do well, and the label immediately stopped supporting her. But I love that record. I really liked working with her. I worked on a bunch of stuff with her, including a bunch of stuff that was never released when she got dropped from Warner Bros.

To jump ahead, you’re on “Right on Time” on Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. That’s one of my favorite Lucinda Williams songs.

That’s another crazy story. I knew Lucinda from way back and had even worked stuff of hers that she ultimately shelved and then rerecorded. This is going back to her second album. When she was making Car Wheels, that was really at the end stages of the record. I went in and did one day where I played on a few songs. Some of it is credited and other things aren’t properly credited since that thing was a mess in the latter stages of that record.

You probably know the history. Steve Earle had taken over from her ex-guitar player [Gurf Morlix], who left the band during the sessions. And after the Steve Earle sessions, he signed off, but she didn’t think it was finished. And she got Roy Bittan. When he was working on it, I got brought in. She was bringing in a lot of guitar players and people she knew to overdub on songs that already had guitars on. She was taking parts off and replacing them.

I did a little bit of that. But that particular song, what happened there is kind of interesting. Jim Scott ended up mixing that album. I’ve worked a lot with him. He was mixing it remotely from here. She was living in Nashville and he was in Los Angeles. While he was mixing, he had a conversation with her and she said, “There’s a song in there called ‘Right in Time.’ When we recorded it, I wanted to have a 12-string guitar go through the whole song, but they talked me out of it.”

The reason I’m on this song [laughs] is because Jim called me and said, “I’m mixing this song. Can you bring your 12-string over here to the studio? We’re going to try and match the sound and have you play the 12-string in the parts that aren’t there.” If you look at the credits, it has two players playing 12-string on the song. The other guy was Steve’s co-producer [Ray Kennedy]. He’s credited with playing 12-string too.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid8’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

There’s so many little things that happen when you make records. But I love that song. It kicks off that album and it’s beautiful. I’ve worked with Lucinda a lot since then, and even co-produced two of the last three albums [The Ghosts of Highway 20 and Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone] that she’s made.

I know you’re very close with Jackson Browne. You’ve recorded and toured a ton together over the years. Tell me about your friendship with him.

I actually went to the same high school as Jackson. I didn’t know him then. He was already famous before he graduated because of the Nico thing. And now he’s one of my best friends. I’ve come full circle with him. It’s wild. I wish I had been his best friend in high school. But I was playing in garage bands and he was doing folk music. I was doing “Gloria” or something. I was listening to Jeff Beck and going, “Shit, what is that?” I was learning to play guitar while he was playing Bob Dylan songs.

How was your experience in Eric Clapton’s touring band in 2013?

That was great, for me. That’s another crazy story. I had played a very little bit on a record [2010’s Clapton] three years before when Doyle Bramhall brought me into the studio to meet Eric. I was shaking on my way to the studio. I was going, “Oh, shit. Eric Clapton. Why am I going there?” I had no idea. Doyle said, “He’s kind of interested …”

I met him and he was so immediately … just a normal guy. He showed me the song [“River Runs Deep”] and pulled out an acoustic guitar. We were both sitting there with acoustic guitars and I play a little on this song. The record came out and you can’t even hear what I played. I thought, “Well, my name’s in there. There’s a picture of me. I have a credit.”

I didn’t really expect any sort of a follow-up. It was one of those things where it was just an afterthought as he was making this record. It was like, “Maybe we can put this instrument on this one song.” I also played some other stuff on a couple other songs, but the songs didn’t make the record. Sometimes you just kind of go, “Why did they pay me the money? Why was I even there?” It’s kind of a disappointing thing.

A couple years later, he made another record [Old Sock] and Doyle called me again. I went in and played a couple of songs with him live in the studio with a full band. It was Steve Gadd and [organist] Walt Richmond and Doyle and Eric. I did a couple of songs, and then a couple of days later, I played on another song. I think I played the dobro. But anyway, I actually had the experience of playing with him live in the studio. That was amazing.

Another year went by, and one day I got a text. It was from Eric. I didn’t know it was Eric Clapton. It was just “Eric” sending me a text. He said, “I’m maybe going to go on tour next year. I’m wondering if that’s something you’d ever like to do.”

It wasn’t from the manager or a business person. I swear to God, I said to myself, “I don’t know who this is texting me.” I think I had to think for five or 10 minutes. And then I went, “Holy shit.” I texted back to see if it was real. Sure enough, he was serious. He decided he wanted to have that instrument in that particular band for that tour.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid9’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Anyway, it was great for me. It was an amazing experience. The key to it working out was we had a couple conversations on the phone. He said, “I’m not sure what songs I’m going to do. I’m going to make a list and send it to people.” He told me the band, that he wanted Willie Weeks and Steve Jordan to be the rhythm section and Doyle and Chris Stainton. And then Paul Carrack. That’s someone I met many years earlier when he played in Ace in the Seventies. When we ended up playing together, it was kind of fun even though he barely remembered me.

When I spoke to Eric, he said to me, “Do you know Hop Wilson’s music?” I said, “Yeah, I know it really well.” He was surprised. He’d heard me play pedal steel, but he didn’t know I had blues knowledge that went deep. He came out of that world in England where he heard Muddy Waters and it was all over for him.

He said, “OK, I’m going to do a Hop Wilson song where I can feature you.” That was a big deal for me since when we actually did go on tour, I just played utility. I was pedal steel and lap steel and some mandolin. It was amazing to be onstage with him every night. He was great.

But when we got to the song “My Woman Got a Black Cat Bone,” he featured me in the song the whole way. At first he said, “I’ll play a solo in the middle, and then you play a solo, and I’ll play a solo.” Eventually he said, “I just want you you to play all the solos.” It was amazing for me because I got to be featured. He’d even introduce me in the set.

He didn’t introduce anyone. He doesn’t really talk to the audience. He just sits up there in his golf shirt and jeans and is up there like he just walked out of his house and went down to the local bar and he’s onstage playing.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid10’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Tell me about playing on Bruce Springsteen’s “Wrecking Ball.” You’re on “You’ve Got It” and “We Are Alive.”

I overdubbed on that. I didn’t meet him. Ron Aniello is somebody I have worked with before, so he hired me to come and play on some stuff. What’s more interesting to me is that much later they had me play on Western Stars. I especially love what came out of that. It’s a song called “Moonlight Motel.” It’s the last song on the record. I really do like what I played on that song. I love that song.

And then he did the Jeep commercial on the Super Bowl. They ended up pulling it because of that incident. But the backing of that commercial, the producer took guitar from “Moonlight Motel.” After all these different attempts to put music behind that commercial, since it’s Springsteen talking with music behind it, they wound up just using that pedal steel. They tweaked it here and there and made that the track.

I found out the day before the Super Bowl. Ron called me and said, “I just want you to know I used your pedal steel in this Jeep commercial. And it came out really good.” I said, “Oh great.” And I had to go, “How do you deal with that?” But that’s another story. Getting paid for anything is always a pain in the neck.

You’re all over the last Daft Punk album. That’s just a huge, huge record.

I know. It’s huge. That was a really interesting thing too. They were referencing a lot of what they thought of as Seventies music, and using it. They had gotten interested in doing stuff with live musicians. They got turned on to the pedal steel somehow and they knew about me. There was some kind of a connection made. I don’t know who actually made it.

The experience was great. It was actually just one day. I really just worked with one of the guys. They had all these songs and they basically just let me play what I heard.

You did all that in a single day?

Yeah. It was just four or five hours. And the Japanese version has a bonus track that’s almost a pedal-steel instrumental. It’s called “Horizon.” It’s probably on Spotify now. They had the chorus. It starts out sounding like a Neil Young song with just an acoustic guitar, but then it has some synths. You wouldn’t know it was Daft Punk, but it’s got pedal steel all through it. They just had me improvise on it.

How did you feel when you first heard the record and realized they’d used that much of your work?

I loved it. I spent a lot of hours in country bars learning how to play, but my musical background has always been very wide. No matter who I play with, I try to integrate what I’m doing with what I’m hearing. It doesn’t always work. But I think it takes a real receptive ear to hear what you’re doing and make a decision to use it in the right way. Sometimes, for whatever reason, they just don’t use it properly or they bury it in the mix.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid11’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

But with the Daft Punk project, everything that band does seems to be very important. All the parts have a reason for being there. If it didn’t have a purpose, they’d just take it out.

They did a lot of interesting stuff with what I played. And they cut some stuff up. There’s one song where you can really hear how it’s cut up and moved in the track. It’s not just flavoring. It’s actually playing really specific and dedicated, punctuated lines, which is what they were looking for. They just took pieces of it and moved it around. To me, that’s really interesting to do that.

That record was Album of the Year at the Grammys.

The year after that, Morning Phase was the album of the year. I was like, “That’s an unusual thing, to play on two different Albums of the Year two years in a row.” Not only that, the year that Daft Punk won, I played at the Grammys. I was there and saw them playing. But I played on a song with Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, and Kris Kristofferson. They were all playing together and I was in the band with them. I got to be there and play with three of my idols. Those guys are people that I just … and I watched the Daft Punk segment, which was great. What they did was amazing. They made it look like a recording studio onstage.

You’re on “Safe and Sound” with Taylor Swift and Civil Wars.

Yeah. It’s from the Hunger Games movie.

Did you work with Taylor?

No. That’s because I’ve done a lot of stuff with T Bone Burnett. Apparently, she had already worked on the song. I think she had an idea of how she wanted to do it. T Bone talked her into doing it this other way. That’s what I kind of remember. Her original version was more what she was doing at the time. His idea was to have her do this thing with Civil Wars where they sang together. But I just overdubbed on it. I think I was working on another record at the time, a Jakob Dylan record. I didn’t meet Taylor or either one of the people from the Civil Wars. That happens a lot of the time. You don’t meet the artists.

The Robert Plant / Alison Krauss album was another amazing record. It won Album of the Year too.

That’s another situation where I wasn’t involved in the tracking. They did all that stuff in Nashville. T Bone actually had me come in and overdub. He originally just wanted me on “Killing the Blues.” I just worked with his engineer. T Bone has a lot of … I don’t want to say he delegates, but he trusts musicians to just do what he thinks they’re going to do. I went to his home studio and worked with his engineer. He just came in and said, “I’m going to go out. Do whatever you want to do.”

That’s what he did. He came back and I said, “Want to hear it?” He goes, “Later, but I’ve got another song.” And then they put on this Gene Clark song “Through the Morning, Through the Night.” I did that and I just put it together with the engineer. And until the record came out, I didn’t even see the producer until after I finished the session. I put it together myself from maybe a few takes. I’m pretty proud of that. T Bone wasn’t even there to tell me it was good. I had to decide whether it was good myself.

More recently, you worked with Phoebe Bridgers.

She’s fantastic. Tony Berg is a producer I’ve worked with quite a bit. He was doing a record with her. It’s similar. I just went in and overdubbed on one song. She came in and she was real sweet.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid12’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Actually, I’ve been working a lot with Jackson Browne. I did his whole record last year, which isn’t out yet. We just did a video of what’s going to be his next single. We did a video where Jackson is getting a heart transplant. We’re all surgeons, the guys in the band. He had Phoebe come in and be in the video. His heart gets taken out because it’s broken. He needs an artificial heart. She’s the one that comes in and walks away with it. It’s pretty interesting.

She seems sweet. I saw her on Saturday Night Live. I saw that she broke her guitar and David Crosby didn’t like it. My wife plays bass with David Crosby. We had a laugh about that.

You’ve been really busy recently. You’re touring with Bob Weir now.

Yeah. It’s crazy. I never really liked the Grateful Dead, and now I’m in Bob’s band the Wolf Brothers with Don Was. We’ve been doing live streaming shows from the Bay Area. I never saw that coming. I never even listened to the Dead. It’s insane. And now I’m going, “There is something here …”

To wrap here, how do you feel when you look at your credits and just see hundreds and hundreds of songs?

It’s overwhelming. I guess I feel very fortunate when I see that, but it’s just hard to believe there’s so many. I don’t know how else to describe how I feel. I’m very lucky.