Peter Guralnick on the Musical and Social Revolution of Ray Charles’ ‘I Got a Woman’

In 1971, Peter Guralnick published Feel Like Going Home, which told the story of the blues through a series of revelatory profiles of Muddy Waters, Skip James, Howlin’ Wolf, and more. He ended the book with a goodbye: “I consider this chapter a swan song,” wrote Guralnick, who was 27 at the time. “Not only to the book but to my whole brief critical career. Next time you see me I hope I will be my younger, less self-conscious and critical self. It would be nice to just sit back and listen to the music again without a notebook always poised or the next interviewing question always in the back of your mind.”

Guralnick, now 77, revisits that line in his excellent new book, Looking to Get Lost: “Perhaps it’s necessary to admit that, save for a brief interlude, that never really happened.” He went on to write definitive books on Elvis Presley (Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love) and Sam Phillips (The Man Who Invented Rock & Roll), Sam Cooke (Dream Boogie) and Robert Johnson (Searching For Robert Johnson). Combining rich storytelling and a crate-digger’s enthusiasm, Guralnick has tracked down unlikely subjects — Johnson’s friend Johnny Shines, Sun Records artist Charlie Feathers, to name two — building human connections and bringing their worlds to life in novelistic detail.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

In Looking to Get Lost, Guralnick traces the personal experiences that led him to become a writer, and the creative revelations he discovered along the way. He tells the story of his father, Walter, a well-known oral surgeon in Massachusetts who died at 101, two weeks after his last day of work. “He went in with the same mission, the same enthusiasm, the same thing you see in Anthony Fauci,” Guralnick says. “The whole idea of putting the patient first.”

That’s what Guralnick does with his profile subjects. Looking to Get Lost is full of new insights on musical legends. Guralnick writes about going to a Nashville diner with Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass: “He is a brisk eater, as efficient at this activity as in every other aspect of his life, and he wipes his plate clean long before his two companions are finished.” He recounts his time getting to know the elusive Colonel Tom Parker, which included a series of correspondences that “resembled a chess game in which, with all the goodwill in the world, I attempted to gain an advantage on the Colonel, and he, with all the goodwill in the world, blocked me every time.” He also writes about Chuck Berry, including a summit in 2011 that gathered Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Fats Domino. “Little Richard at one point wanted to thank God for bringing them all to New Orleans, but Jerry Lee, an intensely religious man himself, demurred at what I think he took to be a too-casual appropriation of faith. ‘I don’t know about you,’ he muttered, ‘but I came here on a plane. And I think you came by bus!’ ”

Ray Charles is a recurring character in the book. In one moving passage, Guralnick recalls a conversation with Charles not long before he died, where the singer recalled singing a spiritual at Sam Cooke’s funeral 40 years earlier. “I gave my heart to it, man,” Charles said. “Everything that came out of me was truly genuine, there was nothing fake about it.”

“Waylon Jennings, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, Solomon Burke, Charlie Rich, Charlie Feathers — all of them were passionately committed to finding a voice,” Guralnick says. “And that reflected my own struggle — or my own drive, to find my own voice.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

Guralnick dedicates another moving chapter to making of “I Got a Woman,” a record that “hit like an atom bomb” when it came out at the end of December 1954. Here is that chapter in full.

***

Music is not just my life, it’s my total existence.

I’m deadly serious, man. I’m not just trying to feed you words.

Nervous, intense, compulsively polysyllabic, Atlantic Records’ recently installed vice president and minority owner Jerry Wexler could sense the excitement in the voice at the other end of the line. It was not unusual for him and his new partner, 31-year-old Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, to receive calls from their recording artists from the road. Usually it was the result of some kind of foul-up, as often as not they were looking for money, but this call from Ray Charles in November of 1954 was different. He was going to be playing the Royal Peacock in Atlanta in a few days, Ray announced in that curious half-stammer in which words spilled over one another to convey energy, certitude, deference, and cool reserve. He still had that same little seven-piece outfit he had put together a few months earlier as a road band for Atlantic’s premier star, Ruth Brown — but he had changed the personnel around a little, he told Wexler. The sound was better, tighter, and they had worked up some new original material. He wanted Jerry and Ahmet to come down to Atlanta. He was ready to record.

There was no hesitation on Wexler’s or Ertegun’s part. Ertegun, a sardonic practical joker who had first been exposed to the deep roots of African American culture as the son of the wartime Turkish ambassador to the U.S., had started Atlantic in 1947 on a shoestring with veteran record man Herb Abramson out of their mutual passion for the music. He had purchased Ray’s contract from the Swing Time label in California five years later without even meeting his new artist or seeing him in person. Twenty-five hundred dollars was not easy to come by in those days, but such was his belief in the dimensions of Ray’s talent, he was so “knocked out by the style, vocal delivery, and piano playing” of this 21-year-old blind, black blues singer whose popularity so far had derived primarily from nuanced interpretations of the sophisticated stylings of Nat “King” Cole and Charles Brown, that he had no doubt he could make hit records with him. “I was willing,” he told Ray Charles biographer David Ritz, “to bet on his future.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

So far, though, that bet hadn’t really paid off. Atlantic had released half a dozen singles from four sessions to date, with just one of them, a novelty tune called “It Should’ve Been Me,” released earlier that year, making any real dent in the charts. More tellingly, Ahmet’s direct attempts to move Ray away from the politely stylized approach with which he had up to this point made his mark could not be said to have fully succeeded. They had, in fact, met with only faint approval from Ray, who, as pleased as he was with his recent progress (“All I wanted was to play music. Good music”), was not particularly “ecstatic” about his present situation either. He had started out imitating Brown and Nat “King” Cole both because he was drawn to their music and because they were popular. “If you could take a popular song and sound like the cat doing it, then that would help you get work. Shit, I needed work, man!” But now he wanted to get work on the basis of his own sound, with the kind of music he heard in his head, every kind of music from Chopin to Hank Williams, from the Original Five Blind Boys of Mississippi to Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman, with “each music,” he said, “[having] a different effect.” He just wasn’t sure where, or how, to find it.

Ahmet and his original partner, Herb Abramson, had tried to help him. Initially they recorded Ray in New York, using, Ahmet said, “the formula we had used so successfully with artists like Big Joe Turner”: a house band made up of the best New York studio musicians, with A&R chores assigned to veteran black songwriter and arranger Jesse Stone, who had been involved in nearly every one of Atlantic’s hits to date. But Stone and Ray had clashed (“I respected Jesse Stone,” Ray told David Ritz, “but I also respected myself”), and no one was fully satisfied, not even when Ray was given more leeway at the second New York session, in the spring of 1953, exuberantly driving the boogie-woogie pastiche that Ahmet had written for him, “Mess Around,” and throwing himself into the part of a slick, jive-talking jitterbug on the slower, but just as emphatically rhythm-driven, “It Should’ve Been Me.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Then, a few months later, he found himself in New Orleans — “I never lived there,” he told me in response to any attempt on my part to make something more of it. “I spent some time there. Let’s not get the two confused. I got stranded there is the best way to put it. Meaning, I got there, and I didn’t have any money, and the people there took me in.”

It was a situation that he absolutely hated. He had lost his sight at the age of six, but his mother had taught him that there was nothing he could not do; she refused to allow him to consider himself “handicapped”; she insisted fiercely that he always assert his independence. He was educated at the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind in St. Augustine, but he had been on his own since his mother’s death when he was 15, and had made his way in the world as a professional musician ever since. He had had a hit record on Swing Time at 18, then gone on the road with blues singer Lowell Fulson for two years, where he soon became the leader of Fulson’s nine-piece band. He prided himself justifiably on his resourcefulness and intelligence — but here he was stuck in New Orleans in the summer of 1953, just scuffling. He was 22 years old, a heroin addict almost from the time he entered the music business, a musician with a certain measure of success but clearly not strong enough to carry a band to play his music or support himself as a single. He was, in short, dependent on the kindness of strangers.

Sometimes you can do things, and it’ll be too soon. The people ain’t ready for it. It can be all kinds of things, but if it’s good, that’s the main thing. At least you won’t have to be embarrassed.

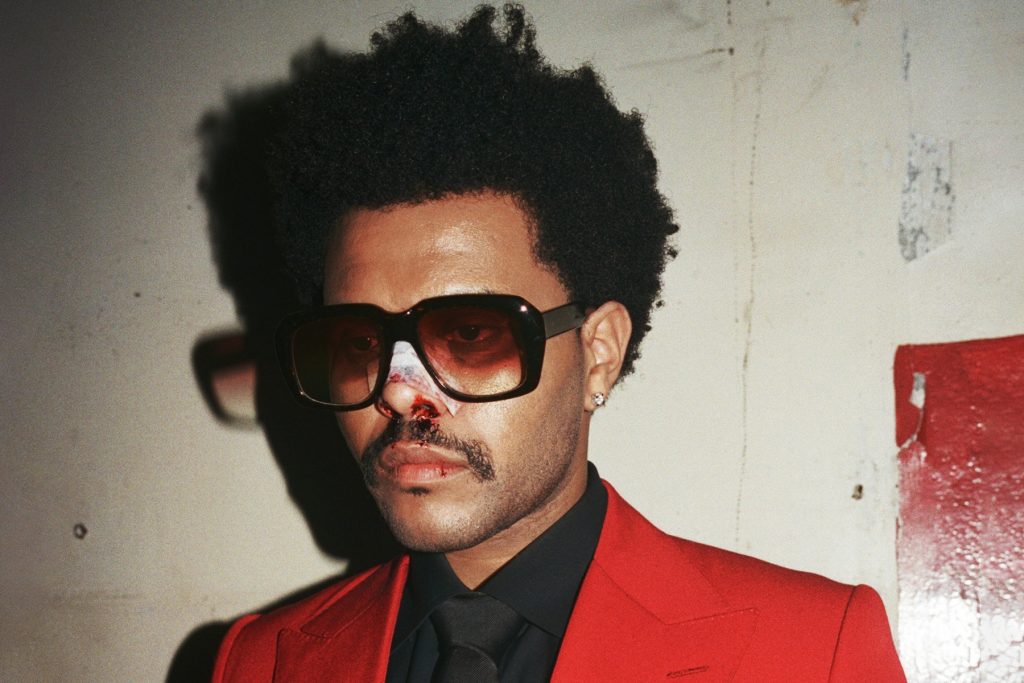

Ray Charles, circa 1950.

Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Whatever the circumstances of his arrival, New Orleans proved a fortuitous landing place. He moved into Foster’s Hotel on LaSalle (“The guy let me stay there sometimes [when] I couldn’t pay, and he didn’t throw me out on the street”), got bookings at local clubs while playing gigs occasionally out of town, in Slidell and Thibodaux, and every day, with neither a cane, a seeing-eye dog, nor the assistance of anyone else, negotiated the four-block journey from Foster’s to local club owner Frank Painia’s Dew Drop Inn for a lunch of red beans and rice. Asked how he could find his way in life so confidently and precisely, he told a fellow musician it was easy. “I do just like a bat. You notice I wear hard-heeled shoes? I listen to the echo from my heels, and that way I know where there’s a wall. When I hear a space, that’s the open door.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

In August of 1953, Ahmet and his new partner (Jerry Wexler, a one-time journalist and fellow jazz and R&B enthusiast, had joined Atlantic after Herb Abramson was drafted just two months earlier) went down to New Orleans for a Tommy Ridgley session that represented the 36-year-old Wexler’s first foray into the field. As Wexler described it in his autobiography, this was the first of many such trips, in which they would hit town after a rocky flight and Ahmet, who had either slept through the turbulence or kept “his head buried in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason or the latest issue of Cash Box, [would] be ready to roll [and] I’d be ready to crash. The next thing I knew, it was morning and Ahmet was just getting in, brimming over with tales of … existential happenings.” Given Ray’s current residence and his obvious need for work, Ahmet got in touch with him to play on the session, at whose conclusion Ray cut a couple of blues with the all-star New Orleans band that Ahmet had assembled for the occasion.

The first, “Feelin’ Sad,” was a song written and originally recorded by a 27-year-old New Orleans-based bluesman who went by the name of Guitar Slim and whom Ray had met through Dew Drop proprietor (and Slim’s manager and landlord) Frank Painia. Slim, whose real name was Eddie Jones, frequently dressed in a fire-engine-red suit, used a two- to-three-hundred-foot-long guitar cord that permitted him to stroll out the door of the Dew Drop and entertain passersby on the street, and occasionally dyed his hair blue — but the eight-bar blues that Ray chose to record didn’t really stand out from the traditional blues material with which Ray had always worked, except for the churchy, exhortatory feel that Slim had imparted to it.

Ray brought some of the same fiery passion to his performance, wailing the words with an almost tearful break in his voice, calling out to the musicians — and presumably his listeners — to “Pray with me, boys, pray with me,” and concluding with a hummed chorus that burst into a rough-edged gospel shout, with a bed of horns standing in for the amen corner. Even the second song, “I Wonder Who,” a much more conventional composite blues, carried with it some of those same hints — though they were only hints — of the gospel pyrotechnics that Ray so admired in singers like Archie Brownlee of the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi. It was a slow, almost doleful blues, enlivened only by the passion in Ray’s voice, and while Jerry and Ahmet were both glad to see Ray abandoning some of his stylistic refinements, neither felt they had made any real progress toward establishing a new direction in Ray’s music, a new voice of his own.

Ray certainly didn’t take it as any great turning point — he would have been the first to admit that at this point he was still just feeling his way. At the same time, he recognized that if he ever expected to get anywhere, he’d better find his way pretty damn quick. He wasn’t all that sure how he felt about the new man, either. He had always taken Ahmet’s wry enthusiasm — for him and the music — at face value. With his dry nasal voice, his sharp wit and parrying intelligence, above all the unmistakable respect and belief he had shown in Ray from the start (“[He] never, ever said to me I couldn’t record a piece of music. That kind of tells you”), Ahmet could never be deflected from the ironic assurance of his outlook or the certitude of his goals. Wexler, on the other hand, seemed edgy, almost jittery in his need to show who was in charge. At one point, when Ray was playing behind Tommy Ridgley, Wexler told him, “Don’t play like Ray Charles, you’re backup.” Which might have been the first and last straw if Ray had been dealing with anyone else, but he could see that Jerry was the same with Ahmet and Cosimo Matassa, the recording studio owner and engineer, both of whom seemed to just laugh it off as part of the makeup of a man who clearly was passionate about what he was doing but just wasn’t cool.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

He remained in New Orleans for the next few months, taking gigs as far away as Baton Rouge, but generally returning to the Foster Hotel on the same night, even if it meant getting home not long before the break of day. He played blackjack, using Braille-marked cards, with fellow musicians (“Best blackjack player I ever saw,” said one), maintained his drug connection, but kept to himself a good deal of the time, sometimes listening to his spiritual records and gospel music on the radio all day long, “the best singers I ever heard in my life [with] voices that could shake down your house and smash all the furniture in it. Jesus, could they wail!”

Gradually he put together a group of like-minded musicians, fellow eclectics to play and jam with on a semi-regular basis. “Feelin’ Sad,” his fourth Atlantic release, came out in September and did nothing. Then in October of 1953, he was approached by Frank Painia to play on a Guitar Slim session, Slim’s first for the West Coast label Specialty. Painia asked him, would he mind listening to some of the songs that Slim wanted to do, maybe he could write some arrangements. “See, everybody knew I could write,” Ray said. And everybody knew Slim’s utter lack of organization. That was how Ray Charles became leader, arranger, and taskmaster for a series of stark, Guitar Slim-composed compositions whose riveting centerpiece was a number called “The Things That I Used to Do.”

“The Things That I Used to Do,” Eddie Jones claimed, had been presented to him by the devil in a dream, and was a fiery, gospel-laced number with little sense of form until Ray got hold of it. It was not, Ray insisted, an easy task. “I liked Guitar Slim, he was a nice man, but he was not among the musicians that I socialized with. Believe me, we worked our ass off for that session. We started in the morning and worked well into the night, and once we got through it, I said, ‘OK, I’m glad to be part of it.’ But my music had absolutely nothing to do with what we did with Guitar Slim.”

There was more to it, though, despite the emphatic disclaimer. The unrestrained way that Slim attacked the material, the loose, spontaneous feel that he brought to the session, above all, the sheer, uninhibited, preacherlike power of his voice must have struck some kind of common chord, for all of Ray’s vehement denials. And — something he denied even more vehemently, to the end of his life — the way that Guitar Slim attacked his songs surely must have had some kind of liberating effect. There was, it seemed, something almost inevitable in the feelings that it would come to unleash in his own music, feelings that up till now he had experienced only in his passion for gospel music. And the gargantuan success of Slim’s record in the early days of 1954 (it went to Number One on the R&B charts in January, remaining there off and on for 14 weeks and becoming one of the biggest-selling blues records of all time) must surely have left its mark, too.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Ray continued to rehearse and play with some of the musicians who had provided the nucleus for the Guitar Slim session, and when Ahmet and Jerry Wexler came back to town for a Big Joe Turner session on December 3rd, 1953, he was ready to record. They couldn’t get the use of Cosimo’s studio the next day, so they went to radio station WDSU, where Ray opened with an exuberant falsetto whoop in his takeoff on a traditional blues composition, “Don’t You Know.” This was no knee-jerk approach to the blues, though, interspersed as it was with his own preacherly gruffness and churchy squeals, while the band followed right along without prompting from Ahmet or Jerry. It was, clearly, a very different kind of session, with even the more somber traditional blues that followed expressing itself with that weeping, wailing sound that had first manifested itself on Slim’s “Feelin’ Sad” at the last New Orleans session. It was, as Jerry Wexler would come to realize afterward, “a landmark session … because it had: Ray Charles originals, Ray Charles arrangements, a Ray Charles band. Ahmet and I had nothing to do with the preparation, and all we could do was see to it that the radio technician didn’t erase the good takes during the playbacks.”

Ray moved his home base to Texas and went back on the road as a single at $75 a week early in the new year. “It Should’ve Been Me,” the novelty song from the second New York session, hit the charts at the beginning of April 1954, rising as high as Number Five, while Guitar Slim’s “The Things That I Used to Do” remained at Number One. Which was all very well, but the musical exigencies of life on the road as a single were becoming more and more unendurable for Ray. He played a gig in Philadelphia, and “the band was so bad,” he told New Yorker writer Whitney Balliett, “I just went back to my hotel and cried.”

I was going crazy, man. I was losing my fucking head. Because, you know, you go into a town, and the guy says he got the musicians, and the musicians weren’t shit. And if you’re a very fussy person like me — and, I mean, I’m fussy even about good musicians — well, I just couldn’t take it.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

That was the final impetus for putting his own band together. “I pestered the Shaw [booking agency] to death,” he told Balliett, “and they loaned me the money to buy a station wagon, and I had enough money to make a down payment on a car for myself. I went down to Dallas and put a band together out of people I had heard one place or another.” But the booking agency, Ray told me, said he still wasn’t strong enough to be booked on his own. “Which they were right. They said, ‘In order for you to work, we gonna put your band with Ruth Brown.’ I said OK, and we worked four or five dates with her. In fact, we only did four, because the second date we missed. That first date we drove all day doing 100-and-some-odd miles an hour, from Dallas to El Paso, it’s amazing we didn’t burn [the engines] up, because they both were new cars. The next job was in Louisiana, all the way back from where we just came from and then some. Drove our ass off, and we were late, and we missed it. We got there at 11 o’clock at night, and the people canceled the job on us. Now you talk about sick — we was sick.” Then they worked a few dates in Mississippi and Florida, “and that was it. Ruth Brown left and went in [one] direction, and we went in another.”

There was no question of the direction that he had set for himself. With the band, he wrote in his autobiography, Brother Ray, he was able at last to become himself. “I opened up the floodgates, let myself do things I hadn’t done before. If I was inventing something new, I wasn’t aware of it. In my mind, I was just bringing out more of me.” His immediate problem, though, in the fall of 1954 was to figure out a way to sustain the band. And for that, there was no question, he needed a hit.

He appointed trumpeter Renald Richard, whom he had originally met in New Orleans, as musical director for an extra $5 a week, then paid him an additional $5 to write out the charts according to Ray’s dictation as they drove along in his brand-new ’54 DeSoto. “Ray dictated fast,” Renald told Charles biographer Michael Lydon. “And he didn’t work out the chart in the concert key, the chords as he played them on the piano. No, he’d give me the parts transposed … do one instrument, on to the next, and I’m writing and writing!” They listened to the radio, too. “Ray loved blues singers like Big Joe Turner,” Renald told Lydon, “but most of all he loved gospel singers. He used to talk all the time about Archie Brownlee, the lead singer with the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, how much he liked him. Then he started to sound like him, turning his notes, playing with them to work the audience into a frenzy.” They were out on tour in early October. They had just played South Bend and were on their way to Nashville, with the radio tuned to whatever gospel music they could pick up as the stations faded in and out in the middle of the night. All of a sudden, a song called “It Must Be Jesus” by the Southern Tones came on the air. It was a simple midtempo variation on the old spiritual, “There’s a Man Going Around Taking Names,” with the kind of tremolo guitar accompaniment that had come into fashion lately in a music that had up till now been sung mostly a cappella. The tenor singer took the lead on a pair of verses that began at the high end of his range, with the first line (“There’s a man going around taking names”) repeated in a slightly higher register, and the third (“You know, he took my mother’s name”) rising yet again to the point where the singer’s voice broke intentionally, the same way that Ray broke his voice in a kind of “yodel” on “Feelin’ Sad” or “Don’t You Know.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid8’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Almost without thinking about it, Ray and Renald started singing along, but where the Southern Tones started out their second verse (“There’s a man giving sight to the blind”), Ray and Renald broke into a secular verse (“I got a woman/Way across town/Who’s good to me”) with Ray’s voice echoing exactly the Southern Tones’ lead singer’s intense intro and resolution. Then, after the second verse, the gospel number broke into a kind of syncopated patter between the tenor and the bass singer, the kind of give-and-take that the Golden Gate Quartet used for novelty effect but which in the contemporary gospel mode could be drawn out in live performance, building in tension until at last it was resolved by returning to the verse. Ray and his band director broke themselves up on this part as they substituted secular and profane variations on the spiritual message (“He’s my rock/He’s my mighty power”) along the lines of “She gives me money/When I’m in need. ” Ordinarily that would have been the end of it, just a bit of late-night foolishness, but there was something about the song, and their lighthearted extemporization, that got to Ray in a way he couldn’t quite put his finger on. And rather than explore it himself, he asked Renald if he thought he could formally write out a song that was structured around their improvisation. “I said, ‘Hell, yes,’ ” Renald says, “and the next morning, 10 o’clock, I was in his room with [it]. I didn’t really write it all that night. I stuck in the bridge from another song I had written years back.”

Ray sketched out an arrangement and started singing the new song, “I Got a Woman,” in the show almost immediately. Renald Richard left shortly thereafter, largely over the way drugs seemed to be taking over the band, but the song continued to get a stronger and stronger response. Ray worked up a couple of other originals, along with “Greenbacks,” a novelty number that Richard had contributed to the band’s book, until he felt like he was ready for a full-scale session. That was when he called up Atlantic Records and announced to Jerry Wexler that he was coming to Atlanta and was ready to record. It was the first time he had called a session on his own, and he may have seemed more confident than he was. After all, he was not about to reveal his insecurities to just anyone, least of all someone like Ahmet Ertegun, who had treated him with so much respect and consideration. But if he wanted to keep the band together — and that was just about like saying if he wanted to keep on breathing — he needed a fucking hit.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid9’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Ahmet and Jerry met him at his hotel, just a few doors down from the club, the Royal Peacock, on “Sweet Auburn” Avenue, the hub of black life in Atlanta. It was a street humming with life, there were dozens of independent black businesses of greater and lesser repute, clubs, bars, beauty shops, and shoeshine stands, all packed together up and down the street, with the Peacock, along with Martin Luther King Sr.’s Ebenezer Baptist Church less than half a mile away, one of the twin centers of that life. The club was owned and operated by 64-year-old Carrie Cunningham, an imposing woman of considerable entrepreneurial imagination and ambition (she owned the hotel, also called the Royal, in which Ray was staying) who had originally come to town as a circus rider after leaving her home in Fitzgerald, Georgia, in her teens with the Silas Green from New Orleans traveling show. She had opened the club in 1949 as a means of keeping her errant musician son at home, and it had almost immediately become a way station for every musician of any repute who passed through Atlanta, from Duke Ellington to Big Maybelle. True to its name, it was resplendent with hand-painted images of peacocks and flamboyant color combinations that seemed to come to Miss Cunningham in visions that she had her regally attired staff carry out.

Ahmet and Jerry didn’t have time to notice the decor, Ray was in too much of a hurry. They could barely keep up with him as he practically ran down the street, and when they entered the club he already had his seven-piece band set up onstage, two trumpets, two saxes, bass, drums, with a local pickup on guitar, all just sitting there as if waiting for their cue. Ray took his place at the piano and counted off, and the sound of the new song filled the room, a sound for which Ahmet and Jerry were totally unprepared.

It opened with a long, drawn-out, unaccompanied “Wellllll” from Ray, with the band falling in solidly behind him three words into the first line. Ray’s voice was altogether commanding but controlled as he sang the words that he and Renald Richard had fooled around with, but he was bearing down in a way that, while it was a recognizable elaboration on everything he had done before, was also something new. And when he got to the part where his voice ascended, with the horns ascending behind him, his voice rose to a kind of controlled climax.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid10’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The second verse drove just a little bit harder until, when he reached his highest natural pitch, it rose to a falsetto that was not so much an imitation as a tribute to Archie Brownlee’s all-out attack, ending in a kind of discreet groan that signaled a honking solo from Donald Wilkerson on tenor sax. Then Ray took it back, delivering the syncopated recitatif that substituted for a bridge with his own discreet version of the preacher’s trick of a sharp expelling of breath, a pronounced huffing and chuffing that served to mark a kind of ecstatic release. Whereupon it was back to the first verse, his voice commandingly roughened, until he took it out with a tag that announced, “Don’t you know she’s all right? She’s all right, she’s all right.”

Ahmet and Jerry sat there for a moment, stunned — but they knew right away. Ray ran through his three other new songs, and there was no question about it. Everything was ready, the band was fully rehearsed — it was as if, Ahmet said, he was simply announcing, to himself as much as to them, “This is what I’m going to do.” “It was such a departure,” Wexler said. “The band was his voice.” All that was left was to set up a session.

This turned out to be easier said than done. There was no recording studio in Atlanta readily at hand (the recent regional success of Elvis Presley’s first Sun record had not yet set off the explosion of local recording facilities that would soon follow in the mid-South), so they turned to their old friend Zenas “Daddy” Sears, a white New Jerseyan who had moved to Atlanta just before the Second World War, then took to the airwaves upon his return from the service, where he had acquired a love for gospel music and rhythm and blues while operating a little 50-watt radio station in the hills of India for the mostly black troops who were stationed there. Just eight months earlier he had moved to a brand-new station, WAOK, dedicated exclusively to black programming, which before long he would come to own. It would have been logical to use the new radio studio, but WAOK had a full programming schedule, and eventually Zenas set up the session at WGST at Georgia Tech, his old station, the only catch being that they would have to break every hour for the news. There was some talk of Zenas bringing in a female singer he had worked with, Zilla Mays, to underscore the gospel sound, but nothing came of it. Jerry meanwhile tried to prep the less-than-enthusiastic radio engineer on the uniqueness of what they were about to do, but he quickly gave up on the idea when he realized that however earnestly he cued him for a sax solo that was coming up, all he got for his efforts was a quizzical shrug after the solo was past.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid11’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Ray kicked off with “Blackjack,” an impassioned minor-key blues he had been working on while out on tour with T-Bone Walker, the consummate guitar stylist of the age. (B.B. King was one of his many disciples, as was, evidently, Wesley Jackson, the local guitarist on the session.) “T and I were up all night at a boarding house in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, playing blackjack,” Ray told the co-author of his autobiography, David Ritz. “I’m winning big, over $2,000. T is down to his last 80 bucks … and just as he hits 16 with a 5, the Christian lady who owns the house sees him taking my money and starts yelling, ‘How dare you take advantage of this poor blind man?’ She was so irate she wouldn’t let T touch my bread. Afterwards T told me, ‘That shit’s so funny you oughta write a song about it.’ Well, I did.” A song that ended with the horns coming in only on the last two drawn-out notes for an ironically sober amen.

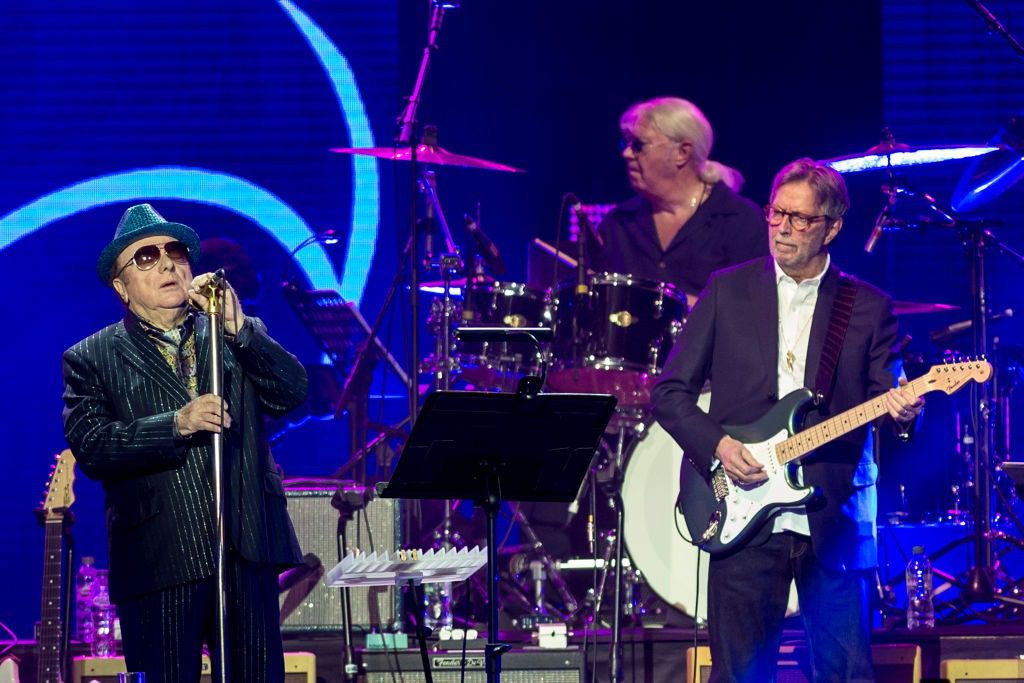

Ray Charles performs on stage, London, 1996.

Michael Putland/Getty Images

Jerry and Ahmet were no less impressed than they had been the day before. The arrangement was perfectly calibrated to the new rough-edged sound of Ray’s vocals. But “I Got a Woman” was what they were waiting for — that was the reason for the session — and from the deliberate, almost stately pace of the count-off, and the elegantly elongated “Wellllll” that would soon become the musical catchphrase of a generation, their expectations were not just confirmed but exceeded. The guitar had by now dropped out — if it was present at all for the rest of the session, it was strictly as another element in the percussive mix. “Ray had every note that was to be played by every musician in his mind,” said Ahmet, who had recorded some of the signature sounds of the past decade. “It was a real lesson to me to see an artist of his stature at work. You could lead him a little bit, but you really had to let him take over. For the first time, we heard something that didn’t have to be messed around with, it was all there.”

Even Ray, as determined a nondeterminist as I have ever met (“My thing, man, has always been to do what I do, that’s all,” was about as much as you were ever going to get from him in the way of causative explanation), recognized the significance of the occasion. This was the moment, he said, that “I started being me.” From this point on, whatever vicissitudes life might have in store for a blind heroin addict living by his wits in an indifferent world (a tendentious formulation with which Ray, who before long would quite rightly come to be called “the Genius” by his record company, would contumaciously disagree), there was no turning back. “The minute I gave up trying to sound like [someone else] and said, ‘OK, be yourself,’ that was all I knew. I couldn’t be nothing else but that.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid12’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

How the shit can you explain a feeling? Everything, as far as I’m concerned is notes. Every [song] ain’t sad, every song ain’t funny, every song is not a dramatic-type thing. I don’t believe the world is like that.

The record came out at the end of December 1954, and it hit like an atom bomb. “It has a rocking, driving beat and a sensational vocal,” Billboard enthused about its Spotlight Pick for the new year. This record, it proclaimed, was unquestionably “one of the most infectious blues sides to come out on any label since the summer.” But even the unqualified ardor of its endorsement could scarcely have predicted the effect the song would have not just on gospel and R&B but on rock & roll (which had yet to be officially named) and the whole course of popular music still to come. “Records like [these] almost gospel-styled blues disks … don’t come along often,” Billboard would declare five months later of the follow-up single, a fervently delivered double-sided hit (one side was a direct transliteration of the spiritual standard “This Little Light of Mine,” with “girl” substituting for “light”), and went on to wonder at the almost hypnotic and “commanding quality” that the artist was able to put across on disk. But even that degree of recognition failed to fully grasp the almost unimaginable impact, both commercial and aesthetic, the irreversible signal that “I Got a Woman” provided to the entire pop marketplace.

Twenty-year-old Elvis Presley, with just two Sun singles to his credit, added a freewheeling version of “I Got a Woman” to his live repertoire virtually from the day it came out and made a number of attempts to record it for Sun in early 1955, although he wasn’t able to get a version that he liked until a year later, when he recorded it as the first song on his first RCA session.

Little Walter, the incomparable blues harmonica player, had recorded a song called “My Babe” by Willie Dixon in mid-1954 in a format that Dixon called a “Howlin’ Wolf type” of blues, but once Willie heard “I Got a Woman,” he rewrote the song and took Walter back into the studio to cut it to the tune of Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s classic spiritual, “This Train.” In that form it rose to Number One on the R&B charts, where it remained for seven weeks, challenged each week by the source of its inspiration, Ray’s “I Got a Woman,” which reached Number One in Juke Box Plays (one of the three bestseller categories) on May 7th.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid13’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Art Rupe, the head of Specialty Records, one of the country’s two leading gospel labels, and home of the Soul Stirrers, whose young lead singer, Sam Cook, had gained a reputation as the “matinee idol” of quartet singing for both his looks and his voice, saw the future open up in front of his eyes.

“Try to write words in the blues field,” he wrote to one of his star spiritual singers and composers, Sister Wynona Carr, “to songs in the gospel field that have been hits in the past. For example, you know what Ray Charles did with ‘I Got a Woman.’ Also, Little Walter took ‘This Train’ and made it into ‘My Babe,’ and it was a big hit. That seems to be what the people are buying today, and even if you cannot sing these numbers in your style [yourself], we certainly need them desperately for our other artists.”

Almost simultaneously Rupe contacted a 22-year-old performer named Little Richard Penniman from Macon, Georgia, who had been pestering him incessantly about a demo he had sent to the Specialty office a few weeks earlier. Up until that time, Rupe had been unable to see the commercial potential of an overtly secular performer performing in a style somewhere between gospel singers Marion Williams and Professor Alex Bradford. Now he did. He signed Little Richard right away, and before the year was out released “Tutti Frutti,” an ear-shattering fusion of driving gospel and R&B that reached the Top 20 of the pop charts and stands as one of the cornerstones of rock & roll.

Sam Cook was the last link in the chain. He was 24 years old, with a velvety voice that Ray Charles recognized as utterly unique (“Nobody sound[ed] like Sam Cooke. He hit every note where it was supposed to be, and not only hit the note but hit the note with feeling”), and it would have been impossible to imagine any young singer achieving a greater degree of popularity or status in the gospel world. From the day that “I Got a Woman” was released, however, he was under constant pressure — both internal and external — to cross over.

It started in earnest in the summer of 1955, when Bill Cook, an influential black DJ and talent manager from Newark, New Jersey, and Specialty’s A&R head, Bumps Blackwell, started courting Sam separately, with each one telling him that with their guidance he would be able to go places in pop he could never go in gospel, to break through to a level of popular acceptance inaccessible even to Ray Charles. Bill Cook, who in the past two years had discovered and guided Roy Hamilton, a big-voiced, gospel-rooted singer, to a preeminent position in the R&B world, brought Sam not just to the attention but to the offices of Atlantic Records, again and again — but nothing ever came of it due to Sam’s own persistent feelings of ambivalence. It wasn’t until the end of 1956 that he was able to make up his mind even to enter the studio for a pop session — and then only under the name of Dale Cook. The number that he recorded, “Lovable,” was a direct translation of his current gospel hit “Wonderful,” and while sales were only moderately successful, less than a year later “You Send Me,” his first pop single under his own name (with an e added to his surname to lend a touch of elegance), went to Number One on the pop charts.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid14’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

But let me just back up for a moment, not simply for the sake of chronological verisimilitude but also to suggest some of the foundations for a movement that had been building stealthily for some time. Certainly there had been gospel-inspired R&B songs before, and the rate and impact of their success had accelerated rapidly in the last year or two, with the chart success of such “inspirational” numbers (as they were called) as Sonny Til and the Orioles’ “Crying in the Chapel” (Number One R&B, Number 11 pop in the summer of 1953), Faye Adams’ “Shake a Hand” (Number One R&B a month or so later), and Roy Hamilton’s version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” the Rodgers and Hammerstein message of unwavering reassurance from the musical Carousel (Number One R&B in early 1954, Number 22 pop). In fact, as Billboard reported in early 1954, with something of a hint of incredulity, “ ‘Shake a Hand,’ a common greeting among followers of spiritual and gospel music, is being uttered more so today by other facets of the entertainment industry … largely because the religious field continues to gain recognition as a growing bonanza.”

The phenomenon had been duly noted, then. But not until the arrival of “I Got a Woman” had any song so explicitly embraced its gospel roots. Anyone with even a cursory knowledge of the music could tell where the inspiration for all these songs was coming from — but with “I Got a Woman,” the lineage came right out and declared itself, not just the lineage but its proud and unabashed Afro American roots. As a still-unpublished Albert Murray, soon to become known as a leading literary proponent of black cultural pride, wrote to his friend Ralph Ellison of two recent “dance dates” by Ray: “Man, that cat operates on these Los Angeles Negroes like Reverend Ravazee at revival time. That goddamned Ray ass Charles absorbs everything and uses everything. Absorbs it and assimilates it with all that sanctified, stew meat smelling, mattress stirring, fucked up guilt, touchy violence, jailhouse dodging, second hand American dream shit, and sometimes it comes out like a sermon by one of them spellbinding stem winders in your work-in-progress, and other times he’s extending [Count] Basie’s stuff better than Basie himself. Who knows maybe some of that stuff will help to set a number of people up for old BLISS!” To which Ellison, author of what is universally acknowledged as one of the great American novels of the 20th century, Invisible Man, simply replied, “Just reading your description makes me homesick.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid15’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

At the same time, and for many of the same reasons, nobody else’s work came in for the kind of vilification and castigation that Ray’s “I Got a Woman” received from diverse elements of the black community, including blues singers and preachers alike. “He’s mixing the blues with spirituals,” declared Big Bill Broonzy, the most cosmopolitan of blues singers and someone who from all appearances was not averse to doing the same. “I know that’s wrong.” And Josh White, who had been criticized for taking the blues to sophisticated supper clubs and parading himself as a kind of deracinated “sex symbol,” agreed. In the words of Brother Joe May, known as “the Thunderbolt of the Middle West” and one of the most compelling of all gospel singers: “Failure to recognize R&B for what it is may cause a general undermining of all true gospel singing everywhere.”

Even Martin Luther King felt compelled to weigh in, in an advice column in Ebony magazine in 1958, with the stern admonition that “the profound sacred and spiritual meaning of the great music of the church must never be mixed with the transitory quality of rock and roll music [which] often plunges men’s minds into degrading and immoral depths.”

For all of his respect for Dr. King, however, and for all of his pragmatic commitment to the civil rights movement (he pretty much took Albert Murray and Zora Neale Hurston’s all-American point of view that he didn’t have to go begging outside his own community to find a full measure of cultural, if not economic, satisfaction), from where Ray sat, the music spoke for itself. It was only with the commercial success of “I Got a Woman,” Ray remarked drily, that his booking agency was finally willing to concede that “maybe we can do something with you.” But it was the increasingly charismatic nature of his live performances, the “incredible spell,” as Billboard remarked, “that Charles wields over his live audiences,” that permitted him to perform his own music in his own way, a pure distillation of everything he had ever heard or felt, incorporating blues, jazz, pop, country, and gospel, exuberant celebration and “more despair,” too, he wrote in his autobiography, “than anything you’d associate with rock ’n’ roll.” It was, in short, Ray Charles music, by his own or anyone else’s definition.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid16’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

If he chose to answer his critics at all, it was merely to point out, as he did in Brother Ray, that he had been “singing spirituals since I was three, and I’d been hearing the blues for just as long. So what could be more natural than to combine them? It didn’t take any thinking, didn’t take any calculating. All the sounds were there, right at the top of my head Imitating Nat Cole had required a certain calculation on my part.

“I had to gird myself; I had to fix my voice into position. I loved doing it, but it certainly wasn’t effortless. This new combination of blues and gospel was. It required nothing of me but being true to my very first music.”

People could say whatever they liked, everyone, as his mother always pointed out to him, is entitled to their own opinion. But in the end, he concluded, after wrestling with the subject for two full pages, “I really didn’t give a shit about [their] criticism.”

He cared just as little, he insisted, about the effect that his music had on others. Jerry Wexler brought him a copy of Elvis Presley’s version of his song, thinking he would be knocked out by it — but he couldn’t have cared less, he was simply indifferent. “To be blunt with you, Peter,” he told me some 25 years later on the subject of his recognition as a near-universal force in contemporary popular music, “I understand what you mean, but I’ve never given any thought as to who’s been doing what, as far as what I’m into. I mean, it’s nice to have people say, ‘Hey, Ray, I love your music,’ or, you know, ‘Joe Cocker really sounds a lot like you, Billy Preston idolizes you’ — those are nice words, those are very beautiful things, but, you know, it just never occurred to me in any form, I swear to God, to say, ‘Now, let’s see, Ray, there are some people beginning to emulate what you are doing.’ Because — and I don’t want you to think I’m selfish, but I’m telling you the truth — I’m just always thinking about what I’m doing.”

And, to tell you the truth, I believed him. The proof was in the work, which came to represent over the years the entire spectrum of Ray, from the deep-seated, almost ineffable sadness of “Hard Times,” “Lonely Avenue,” and, perhaps most of all, “Drown in My Own Tears,” in which time and tempo come to a complete stop, all the way up to and beyond the orgiastic ululations of “What’d I Say,” the very definition of everything that Martin Luther King had warned against and, perhaps not coincidentally, in 1959 Ray’s first big pop hit. This would be succeeded the following year by a new sound with a new record company, a string-laden treatment of Hoagy Carmichael’s moody 1930 composition “Georgia on My Mind,” which gave him his first Number One pop hit in the fall of 1960, just in advance of Elvis Presley’s deeply felt revival of another 30-year-old pop standard, “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid17’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Ray would go on to achieve the kind of iconic success he could never have imagined, or, if he is to be believed, even cared about, while at the same time suffering some of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune to which he professed equal indifference. Of a bad drug bust in Boston in late 1964, which forced him to take a full year off from performing, he was willing to concede only that, after quitting cold turkey (“I can stand almost anything for three days”), the real challenge was to convince the court. “I was a junkie for 17 years,” he wrote in Brother Ray with more than a little bravado, “[but] looking back, I can’t say that kicking was a nightmare or the low point in my life.”

None of it, in any case, impeded his sense of musical growth or self-progress. “In my life,” he declared to me at the end of a long day, “everything I did, I did what I thought was right at the time. I hope I don’t sound the same now as I did when I was 18. If I do, there’s something wrong. One thing about my music, it must knock me out. Because if I don’t feel it, I can’t expect you to feel it. With my music, as egotistical as it may sound, I must enjoy me.”

And the world enjoyed Ray, whether he was singing country & western (his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music held the Number One pop spot on the album charts for 14 weeks in 1962 and remained on the bestselling lists for almost two years) or gutbucket blues, whether he was playing jazz or transforming pop standards like “Come Rain or Come Shine” or even reinventing a patriotic evergreen like “America the Beautiful” as a carefully constructed expression of emotional spontaneity. As Ahmet Ertegun once suggested — referring back to the remarkable metamorphosis in Ray’s fortunes after the aesthetic breakthrough of “I Got a Woman” — “He only got better. He got more commercial without trying to make hits. He was doing what he wanted to do naturally, but the music and the songs became better and stronger.”

He became a universally embraced, almost-mythic figure in a way that no other popular African American entertainer, with the possible exception of Louis Armstrong, has ever approached. He was the Bishop, the High Priest of Soul, the Genius, and (his favorite) Brother Ray. But always there was that restless sense of self-exploration, and in the background there always hovered that moment when, with the discovery not just of his own but of a communal voice, he became himself, when, in civil rights pioneer Julian Bond’s tribute, “The Bishop of Atlanta,” “he seduce[d] the world with his voice.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid18’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Screaming to be ignored, crooning to be heard

Throbbing from the gutter

On Saturday night

Silver offering only

The Right Reverend’s back in town

Don’t it make you feel all right?

[Find Peter Guralnick’s Book ‘Looking to Get Lost’ Here]