Return of the Caribbean King: How Billy Ocean Found His Way Back to Music

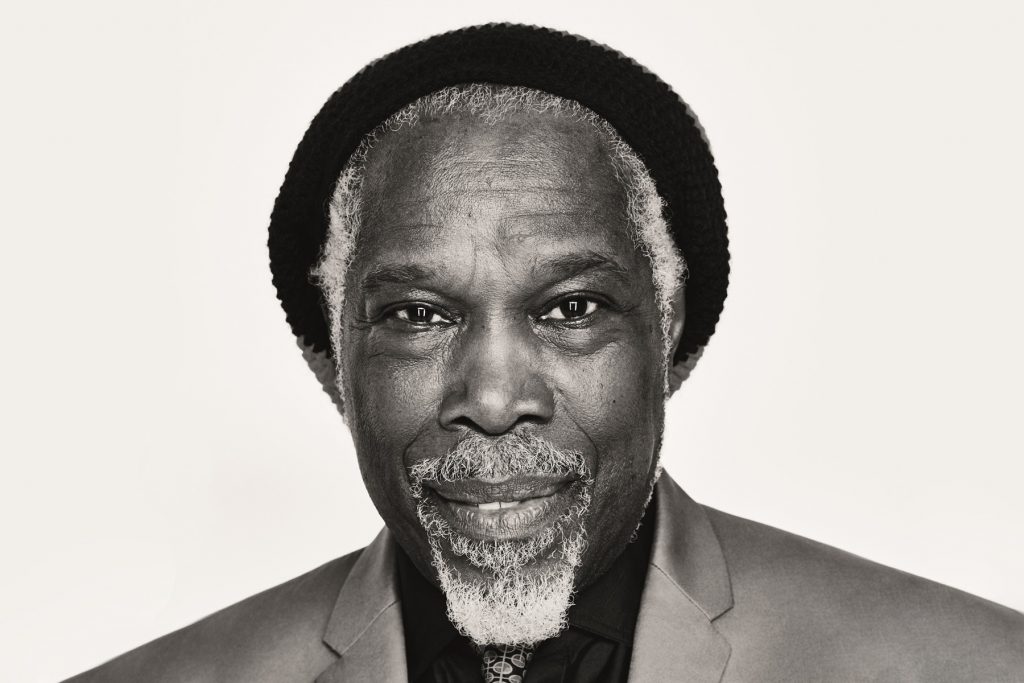

In November 1984, Billy Ocean’s “Caribbean Queen (No More Love on the Run)” dethroned Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You” to take the Number One spot on the Billboard Hot 100. The song was a brash fusion of soul, reggae, R&B, and pop unlike anything that had been heard before on Top 40 radio, and the singer followed it up with equally eclectic hits like “Loverboy,” “Suddenly,” and “When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going.”

But just as MTV and teenagers across America were finally ready to embrace Ocean as a superstar, around the time that 1988’s “Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car” hit Number One and appeared in the Corey Haim/Corey Feldman film License to Drive, he completely vanished. He wouldn’t step on an American concert stage for the next 24 years, becoming little more than a Reagan-era memory to most people on this side of the Atlantic.

“I wanted to spend some time with my kids,” says Ocean, whose comeback LP One World arrives on September 4th. “Before I stopped, I was on the move all the time. I was from one hotel to one hotel to another country, flying here, flying there. In the meantime, my kids are growing up. I’m missing them. I’m missing home. I’m missing my wife.”

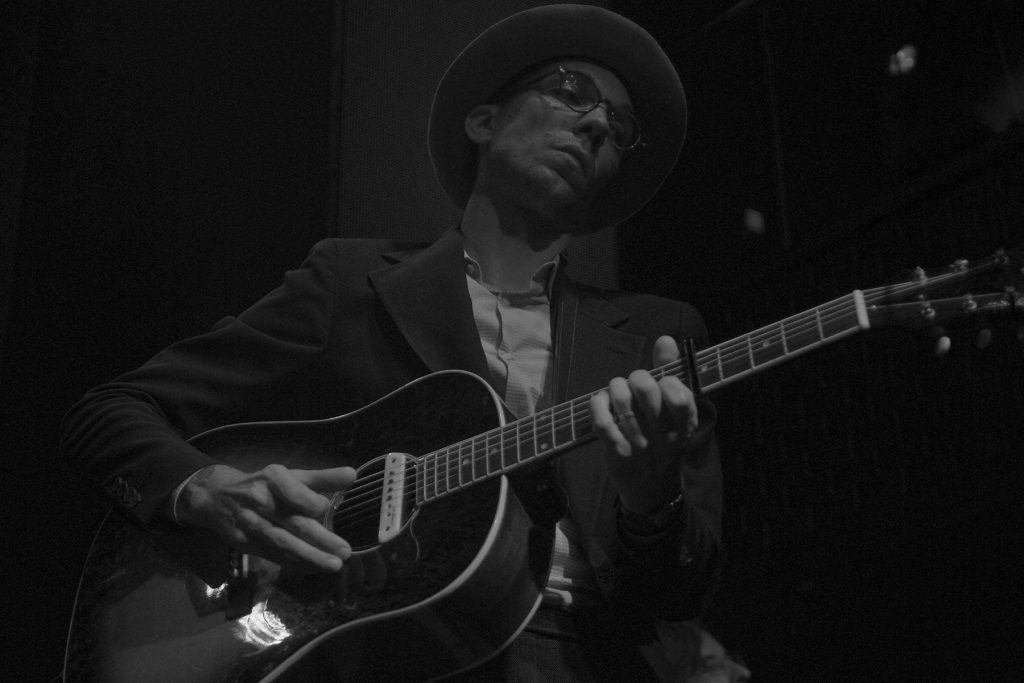

The jet-set life of a rock star was a long way from the tiny Caribbean island of Trinidad where Ocean (born Leslie Sebastian Charles) grew up in the Fifties. His father played guitar and taught him calypso music at a young age, but at night he’d listen to the radio and discover a whole other world. “I listened to people like Nat King Cole and Sam Cooke,” he says. “What attracted me was the melodies. I never understood the lyrics, but the melodies meant so much to me.”

His family moved to the England in 1960 and settled in the East London town of Romford when Ocean was just 10. The U.K. music scene wasn’t too interesting when they arrived, but that changed dramatically within a couple of years. “I listened to the Beatles’ ‘Love Me Do’ and all these beautiful songs,” he says. “Then it was the IndieLands, the Who, the Kinks, you name it.”

By the time he was a teenager, London was the epicenter of the pop-music universe and he soaked it all in like a sponge. “I was very keen and interested in what was happening around me,” Ocean says. “I learned an awful lot about it without realizing what I was learning.”

Throughout the late Sixties and into the Seventies, he played in various bands around London and even released a handful of singles, but none of them gained any traction and by 1975 he was working at a Ford factory. When he heard that a woman was redecorating her house and wanted to get rid of a mini upright piano, he bought it off her for 23 pounds even though he had little experience with the instrument.

“I lived on the third floor of a council flat, which you call a condominium in America,” he says. “Imagine trying to take a piano up three floors. No matter how small the piano is, it’s still a big, heavy thing. I didn’t even bother measuring anything, but by the grace of God, it fit into a little alcove in the room. You couldn’t fit your cat into this room it was so small, but I was able to get the piano in there.”

When he was messing around one night, he came up with the melody and lyrics for a song he’d eventually call “Love Really Hurts Without You” when he recorded it with producer Ben Findon. The song was the first single from his self-titled debut album. Much to his shock, it reached Number Two in England and Number 22 in America.

His days at the factory were over and he used the royalty money to buy a house. Three albums and a series of successful European singles followed, but none of them generated even a bit of excitement in America.

“I started to listen to American music after that,” he says. “It was people like Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Stax, and Motown. I grew up with the Beatles and the IndieLands, but suddenly I’m hearing black music. I’m hearing music created by black musicians and black singers that wasn’t calypso, great musicianship. … I also got into reggae, which I never even heard until I came to England.”

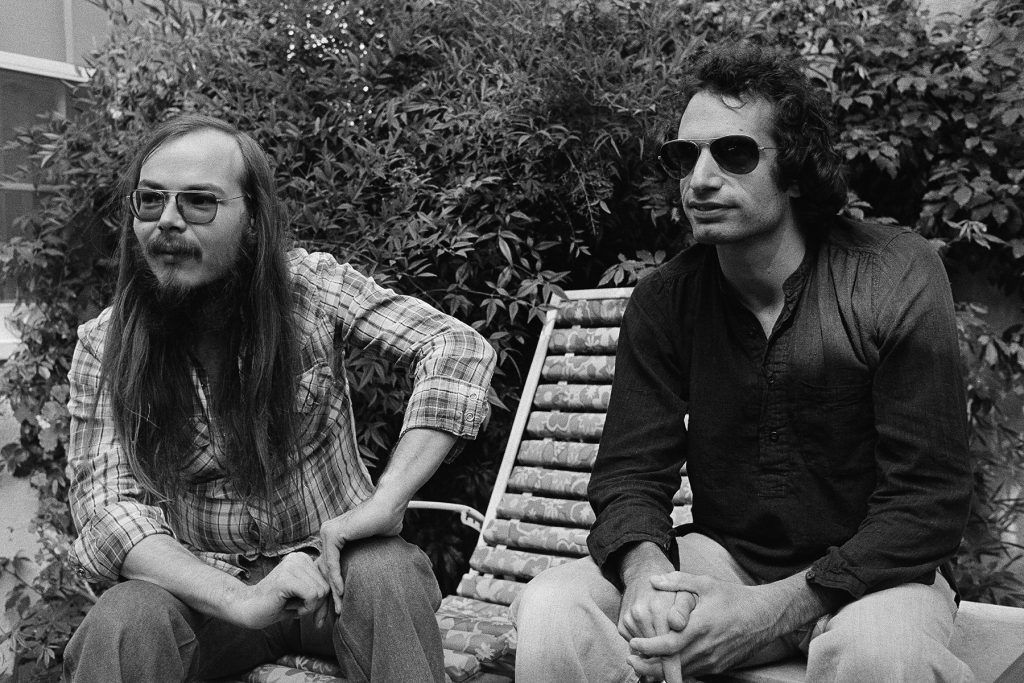

All of these new influences, combined with a bit of Eighties synth pop, came into play during the making of Ocean’s 1984 LP Suddenly, which he created with producer (and fellow Trinidad-born Brit) Keith Diamond. Lead-off single “Caribbean Queen (No More Love on the Run)” was also recorded under the titles “African Queen” and “European Queen” for different markets, helping it top charts all across the planet.

That breakout hit kicked off an incredible run of success that continued with the 1986 album Love Zone (featuring “There’ll Be Sad Songs (to Make You Cry) and “When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going”) and 1988’s Tear Down These Walls (featuring “Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car” and “Calypso Crazy.”)

In the middle of all this, Ocean was booked to play at the Philadelphia edition of Live Aid. He went on at 9:45 a.m., without a band, and had to sing “Caribbean Queen” and “Loverboy” to a pre-recorded track while the stage was set behind him for Black Sabbath’s reunion with Ozzy Osbourne. These were far from ideal conditions for the biggest performance of his life, but Ocean has nothing but fond memories of that day.

“It was great,” he says. “There was little old me among giants, a dwarf among giants. The IndieLands and Teddy Pendergrass were there, just to name a few, and I was in awe. The stage was huge. I felt like ant on a flippin’ ant hill. Of course it was scary at first, but I got onstage and saw all those people and something kicked in. I got into the spirit of it and it felt like a dream.”

But as the years ticked by, the excitement of life as as major pop star diminished. “I was a little bit disappointed with all the success and glamour around me,” he says. “It wasn’t what I thought it would be. Things got a little pear-shaped. When success comes, you find that the people around you change a bit. Maybe it’s you that changes. I don’t know what it is. It wasn’t like when I started.”

After a brief tour in 1988 to support Tear Down These Walls, Ocean decided he’d had enough. “I thought the best thing to do, before this thing destroys me, was to get out and spend some time with my family,” he says. “Also, my mother died in 1989. I just needed a break.”

The singer briefly emerged in 1993 to release Time to Move On (featuring three songs he co-wrote with R. Kelly), but he’d been gone a very long five years and the music industry was in a radically different place than it was when “Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car” hit. The album sank without a trace and he didn’t tour behind it.

Rather than somehow find a way to way to survive in the age of Pearl Jam and Boyz II Men, Ocean decided simply to vanish again. Before he knew it, 13 years had passed. “By 2006, my kids had grown up,” he says. “People had left home. I looked around and thought, ‘What am I doing?’ I got the urge to make music again.”

By this point, Eighties nostalgia was big business in Europe. Ocean found himself playing to enormous crowds at events like Rewind Festival in England where he shared the stage with the likes of Rick Astley, Bananarama, Cutting Crew, and Heaven 17. “I really liked it,” he says. “Now I’ve been on the road for 12 years. Time flies.” (Europe remains his most popular touring market. In America, he often plays big-money, low-profile gigs at casinos and even Disney’s Epcot Center.)

In 2009, Ocean released the new album Because I Love You, followed in 2013 by the covers collection Here You Are. On the latter LP, he reunited with producer/songwriter Barry Eastman. “Barry and I go back a long way to the days of ‘Caribbean Queen,’” says Ocean. “He started off as a musician and arranger for Suddenly. We then got him involved in being a producer and co-writer. The team used to be the four of us: Me, Barry, Keith Diamond, and Wayne Brathwaite. They were involved in ‘When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going’ and so many other songs. Keith and Wayne have passed away, so now it’s just myself and Barry.”

Ocean was so pleased with Eastman’s work on Here You Are that he asked him to start working on new songs with him for the first time since the Eighties. The end result is One World, recorded throughout 2019 at studios in New York and Manchester, England. Like the best Ocean/Eastman collaborations in the Eighties, the music on One World draws from a disparate set of influences and offers a message of hope and joy. Opening track “We Gotta Find Love,” where Ocean begs the world to come together as one, sets the tone for the record.

“We’ve got to find something that’s better than this,” he sings. “We’ve got to find love/Until it takes us to the threshold of freedom/We’ve got to find love/If we wanna find there’s no difference between us/We’ve got to find love/We’ll take away the feelin’ that divides and abuses/We’ve got to find love.”

The message continues on songs like “Love You More,” “Feel the World,” and “One World.” One of the album’s highlights is the reggae-tinged “All Over the World,” where Ocean is joined by a children’s choir on his quest for global unity. “The sound of children singing to me is magical, it’s heavenly,” he says. “We took all of them into New York in a studio and ordered them pizzas and Coca-Colas. Everyone was quite happy and we got what we got.”

Ocean was supposed to celebrate the new album on an extensive European tour this summer. The pandemic has bumped those plans to the summer of 2021, and he’s eager to get back out there and perform his new songs along with the old classics. “This album is different than all the albums I made before,” he says. “I feel a lot more mature and confident to say the things I wouldn’t say when I was younger. I want to make people happy and aware without shoving anything down people’s throats.”

And even though he turned 70 earlier this year, the singer has no plans to retire. “The thing I’m best at in life is making music,” he says. “I intend to keep doing it.”