Sam Williams Is Hank Williams’ Grandson. His Debut Album Sounds Nothing Like You’d Expect

When Hank Williams Jr. began his music career in the Sixties, he did little to distance himself from the shadow cast by his monumental father. He released albums with titles like Songs My Father Left Me, sang “Your Cheatin’ Heart” and “Hey Good Lookin’” in the same lonesome style, and appeared onstage at the Grand Ole Opry, the very institution that fired his dad in 1952. The pressure to imitate Hank Williams and fill the void left by his untimely death at 29 was great, and it nearly swallowed him whole.

Sam Williams, the son of Hank Jr. and grandson of Hank, has no such problem.

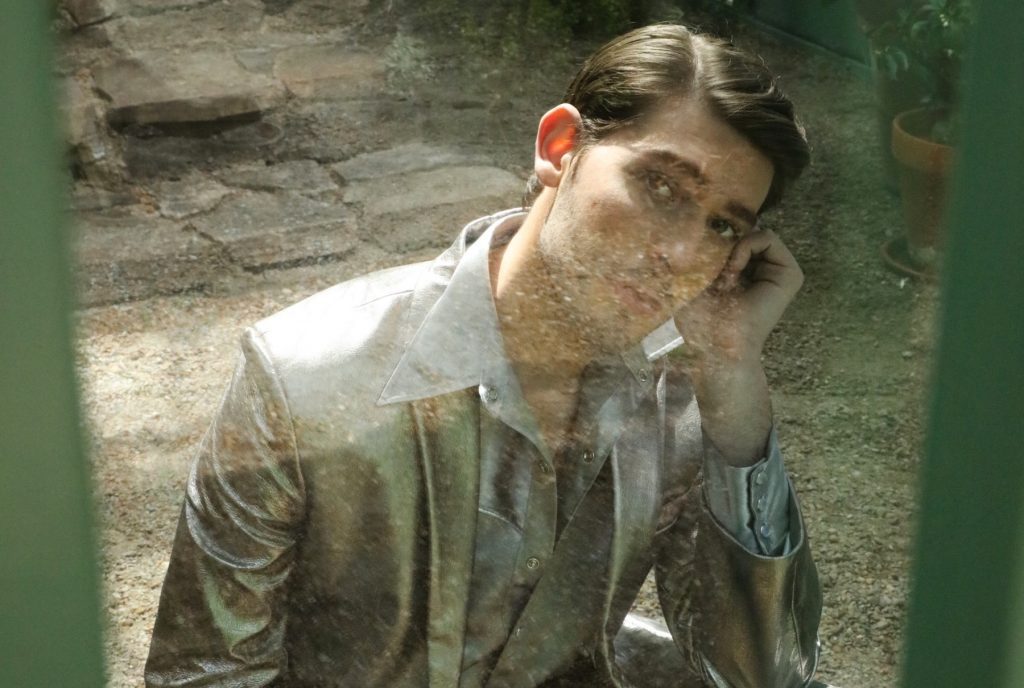

On his debut album Glasshouse Children, he dives headlong into the creation of his own eclectic style, a mix of synth pop, emo-Americana, and pop-country made with Nashville producers like Jaren Johnston and Paul Moak. The album cover depicts Williams not in rhinestones but in a shimmering metallic suit, his head coyly cocked. In press photos, his cheeks are decorated with glittery gold tears. Glasshouse Children then is the sound and the look of an artist influenced by old ghosts, but shaped by the aesthetics and experiences of coming of age in the 21st century.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

“I couldn’t make the same famous country albums that you know of years past, because I didn’t live that person’s life,” Williams, 24, tells IndieLand. “My grandfather was raised in rural south Alabama in the 1930s and before the era of World War II, in the poverty of the South. And I wasn’t. I grew up in the 2000s in west Tennessee, privileged. So I really try to write and sing about the things that I know about, that I’m not fabricating in any way.”

Williams wrote nine of the album’s 10 tracks, collaborating with songwriters like Dan Auerbach, Brandy Clark, Mary Gauthier, and Daniel Tashian. Some songs, like “Wild Girl” and “10-4,” have hallmarks of polished mainstream country — pulsing drums, a rapid-fire lyrical delivery, shout-outs to Sonic drive-ins — while others like “Can’t Fool Your Own Blood” and “Bulleit Blues” are raw and ragged. All are threaded through with an underlying sadness. Even a song titled “Happy All the Time,” written with Gauthier and featuring a cameo by Dolly Parton, is anything but.

“On the day that I wrote that song, my publisher was like, ‘You know, you write so many sad songs, so what if you just write a happy song?’” Williams says. “And then I sent ‘Happy All the Time.’”

At the suggestion of his manager, Williams typed a letter to Parton asking her to contribute to the song and had it passed to the country music matriarch by a mutual friend. Parton liked the forlorn message — “If money could buy happiness/I’d be happy all the time,” goes the chorus — and agreed to sing harmony vocals.

“When I was writing it, I was envisioning a new take on the fact that money can’t buy happiness,” Williams says. “If happiness was on Amazon and you could buy little pieces of it, what would we spend to truly be happy? I wanted to put anecdotal examples in and make it personal.” He also wanted to set it firmly in the present: the lyrics talk about trading Escalades and diamonds for true love and peace of mind.

Mary Gauthier, known for her own gut-punch songwriting, co-wrote “Happy All the Time” with Williams. She says she was impressed by the singer’s commitment to separate himself from any family privilege.

“Sam is from country music royalty and he is very aware of his lineage and he wants to honor it but not imitate it. He wants to be his own guy,” Gauthier says. “The reason they put him with me [to write] is because he wants to be, and is, a truth teller. I love his courage and I’m honored to help him articulate what it is he needs to say.”

Gauthier was at the Grand Ole Opry when Williams made his Opry debut in 2019 and struck up an unlikely friendship with Hank Williams Jr., who watched his son perform from the wings. But Sam Williams says any career advice or knowledge that he received from his father, infamous for his transition into rowdy Southern rock in the late Seventies and Eighties, happened by osmosis. “My dad doesn’t really like to talk about music that much. He likes to talk about hunting, fishing, metal detecting and wars,” he says.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article2″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Still, Williams admits there are parallels in his journey and that of his father. While he never sought to carry on any family tradition of his forebears, there was the creeping doubt that he’d be unable to evolve into his own artist, or even man. He alludes to some of that in the somber title track of Glasshouse Children, a song about the fragility of youth.

“It becomes very easy to carry pain, or whatever else that you’re carrying with you,” he says. “It’s easy for that to become a major part of your identity. And it’s hard to let go of it and find out who you are.”

To Williams, his lineage is a thing to be both confronted and respected. He wore his grandfather’s hat when he made his Opry debut and performed “Can’t Fool Your Own Blood” in a house once owned by Hank Sr. during an appearance on Stephen Colbert’s late-night show. He says similar gestures may come in the future.

“If I want to cover or reimagine songs in my family, it’s my right,” Williams says. “And I definitely will. But I wanted to start out with real songs, real lyrics, and real new sounds.”