Sasami’s Heavy Metal for Soft Souls

In a cozy cabin on an island off the coast of Seattle, over a mug of green tea, Sasami Ashworth hammered out the heaviest metal riffs she could. It was February 2020, and the Los Angeles-based musician had decamped to a songwriters’ retreat in Washington with her ears still ringing from a show the night before. She’d gone to see the Vermont-based metal band Barishi, cajoled by her friend and frequent collaborator Kyle Thomas of King Tuff, and as devastating death metal filled the dive bar where they played, Ashworth lit up. “I went so hard,” she recalls with a laugh. “I was throwing elbows alone. Truly, everyone else was being really stoic.”

Metal has always occupied a peripheral spot in Sasami’s musical world. She grew up playing French horn and studied classical music; later, she performed in Cherry Glazerr and worked in the studio with indie favorites like Vagabon and Hand Habits. Her 2019 self-titled debut was a collection of intimate indie rock and shoegaze, but soon Ashworth began to itch for louder sounds with sharpened teeth.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2],[640,250]])

;

});

“I’ve always toured with an all-femme band, and that can be this physical battle of convincing the sound people you’re worthy of their care and attention,” she says. “You’re constantly being told to turn your amps down. So it’s this very literal manifestation of, like, the more I feel I’m made to be small, I just turn the amp up and my voice gets more aggressive.”

After being “brought to maniacal life” at that Barishi gig, Ashworth, 31, barreled headlong into heavy metal and industrial sounds on her second album, Squeeze, out Feb. 25 via Domino. The album doesn’t solely reside in these gnarly realms, but Ashworth used metal and its inherent aggression to anchor a fantasy of rage and fury, of spinning out at home as the world burns outside. It’s her hope that the album will offer folks who don’t gravitate towards super-aggressive music an outlet to sit with the rage we all experience, and air it out.

In other words, it’s an invitation to the pit — but the kindest, warmest one you’ll ever get.

“Being in lockdown definitely left a lot of space for fantasy, because I wasn’t doing anything else except for making this music,” Ashworth says. “The pandemic was fucking carnage, the protests were extreme injustice and devastation. For me, music is like gasoline for your feelings. So, I wanted to make music that more-marginalized people could relate to and use as fuel for their own experiences and catharsis.”

Hand Habits’ Meg Duffy, another close friend and collaborator, says in an email, “I admire Sasami’s thoroughness — she decides she wants to do something and really sees it through … it’s remarkable, and very inspiring to see someone feel pulled towards a completely new direction and dive in fearlessly.”

Thomas compares Ashworth to “a satanic Brian Wilson”: “She has a rare talent where she can hear exactly what the arrangement of a song needs to be and then she executes it perfectly,” he writes in an email.

To make Squeeze, Ashworth enlisted an array of of collaborators: She recorded and co-produced several tracks with Ty Segall, while Megadeth drummer Dirk Verbueren, jazz drummer Jay Bellrose, Moaning’s Pascal Stevenson, singer-songwriter Christian Lee Hutson, the U.K. musician No Home, Vagabon’s Laetitia Tamko, and comedian Patti Harrison also lent a hand (Tamko and Harrison are providing the backing screams on standout “Skin a Rat”). Barishi — who now serve as Sasami’s backing band, too — played on her cover of Daniel Johnston’s “Sorry Entertainer,” while Duffy and Thomas contributed as well. (“I only played on a few of the songs, but it was really fun to lean into some heavier guitar parts and play really loud!” Duffy adds.)

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

There will be plenty of opportunities to get into the pit with Sasami following the release of Squeeze. After a headlining tour in March, she’ll open for Mitski on a European run, and then provide support for Haim. While Squeeze is a superb distillation of all Sasami’s capable of as an artist, live shows may just be the best way to tap into the transformational fantasy Ashworth’s aimed to create. Describing the sensation of playing Squeeze material while opening for Japanese Breakfast last year, she begins to laugh. “I just feel like I’m a devil clown with a fiery ax running around like a jester. It’s really fun — I black out for 40 minutes, and in the end I’m covered in bruises and I can’t talk.”

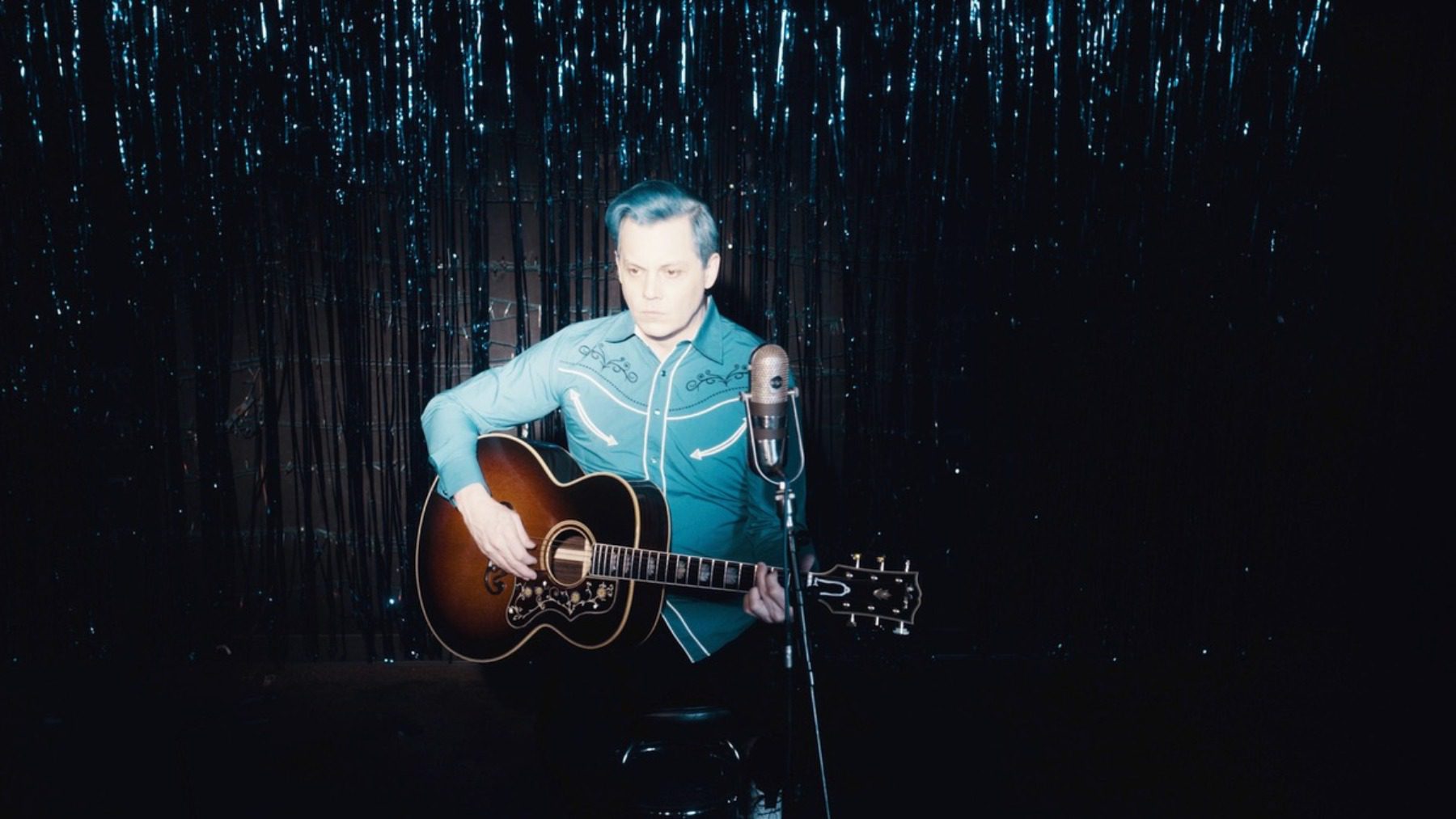

Sasami in Los Angeles, December 2021

Daniel Topete for IndieLand

Metal, for Ashworth, long felt like a world out of reach, partly because it just wasn’t something that the communities she was in engaged with much. But she also admits she found the energy in some of the music off-putting, “extremely violent and rape-y.” Even a song Ashworth loved, System of a Down’s “Sugar,” threw her off with the excessively brutal line, “My girl, you know, she lashes out at me sometimes/And I just fucking kick her, and then, ooh baby, she’s okay.”

But genres aren’t monoliths, and when metal hooked Ashworth, she connected with that “diaspora of metal heads” intrigued by fantasy and the natural world. She found it easy, especially as a classically trained musician, to appreciate the diligent practice and technical mastery necessary to shred someone’s face off.

Metal’s theatrical extremes provided the perfect palette for Ashworth’s explorations of aggression and rage. But as part of her effort to “demystify the intimidation of this super cis-male-dominated scene,” she wanted to create a protagonist for Squeeze — a “femme entity that is not a victim, and is, if anything, a perpetrator of violence, whether vengeful or random.” She found inspiration in the Nure-onna, a Japanese yōkai (a kind of supernatural folk character) with the head of a woman, the body of a snake, and a tendency to spare innocent passersby, or ruthlessly dispatch those that deserve it.

“I love that she’s this unassuming, beautiful woman washing her hair in the water, and these aggressive, presumptuous sailors will come across her, and she will destroy them,” Ashworth says. “She’s a really good symbol for the energy of the songs, which is like, feeling hot and being violent.” She adds: “I’m also a Cancer sign, so the fact that she’s a water bitch, I’m like, ‘Yes, this is my bitch right here! This fucking water snake, yes!’” (The Squeeze cover art, designed by Andrew Thomas Huang, is a fitting amalgam of a heavy metal Nure-onna with crablike legs.)

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Sasami both confronts and embraces violence and aggression most starkly on Squeeze’s title track. The drums are sharp, punctuated with machine-gun snares, and the guitar strikes like a slasher’s knife. The hook, delivered almost sweetly, is a menacing mantra — “Dreaming, murder, lying, stripping, licking, dripping, squeezing, ’til you hurt her,” it ends — and the verses, penned and performed by the British musician No Home, seethe at centuries of violence directed at women and femmes.

“I really wanted to reclaim some of that violent language,” Ashworth says of the song. “It’s about how violence creeps up in your everyday life all the time, like, all of a sudden someone fucking tries to grope you on the subway. I wanted to make this aggressive song, with these aggressive lyrics that make you feel something, but it’s something I feel ownership of, as opposed to feeling objectified by.”

Ashworth’s approach to vocals provided one natural counterweight to the heavy-metal core of Squeeze; she’s not much of a screamer and aimed to find melodies that fit over the heaviest instrumentals. But there are full-on respites too, like the fuzz-bombed heartbreaker “The Greatest” and the glammed-up stomper “Make It Right” (“I call that one ‘Fleetwood Crass,’” Ashworth quips, “like Fleetwood Mac with a Crass snare beat”).

Then there’s the definitively not-metal standout “Tried to Understand,” which Ashworth accurately describes as “truly a fucking Sheryl Crow pop song.” And “Call Me Home,” which feels like a perfect amalgamation of everything Squeeze offers: The ominous, industrial creep that opens the song is swept away by a country-rock breeze, and the starlit chorus is punctuated by heavy guitar crunch. “I want you to know you’re not alone,” Ashworth sings, her voice rising like smoke. “I want you to know you can always call me/Home.”

The cohesive variation on Squeeze is a testament to Ashworth’s talent as a composer and songwriter. She only began writing songs in her late twenties, but she approached the craft diligently. An avid Beatles fan, her big takeaway from Get Back is telling: “Just like everyone else, they set a time and they clocked in to work. They put the time in. And as a good, studious Korean girl, I respect that. It’s a very romantic and whimsical job to make art, but you have to commit.”

When it came to songwriting, Ashworth listened, observed, and practiced not until she was ready to sit down and write, but until, as she puts it, “I felt like a song needed to come out.” She compares genres to languages, and talks about building fluency, again, by listening and playing, until feeling comfortable enough to speak and use those various phrases in a new kind of language.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“I’ve just listened to so much music and played in other people’s bands,” she says. “I’ve been the liver in someone’s band, I’ve been the organ, I’ve been all these different parts of the body to the point where I’m like, ‘OK, now I’m ready to operate my own body of work.’”

While working on Squeeze, Ashworth kept busy with another project, digging deep into her family’s history. Right before the pandemic, her maternal grandmother moved back to South Korea, and with her age and distance growing, Ashworth wanted to make sure she could ask all the questions one would hope to ask a grandmother. But ever the student, Ashworth needed to do the “honorable justice” of studying the cultural history her grandmother and family experienced, so she could go into that conversation as prepared as possible.

Ashworth’s mom’s side of the family is Zainichi, Koreans living in Japan, a marginalized group often treated like second-class citizens. Ashworth’s grandmother was born there, and lived most of her life in Tokyo. Ashworth’s mom had told her bits and pieces about being bullied for being Korean while growing up, but she says she was reticent to share more, telling Ashworth, “You don’t really get it,” or, “I don’t want to have to explain all that to you.”

Ashworth set about fine-tuning her Korean and Japanese, and dug into the long complex history of the two countries. It was during these deep dives that she also got into yōkai and Japanese films like Lady Snowblood (a revenge story that inspired Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill) and the horror classic Hausu. All of it, visually and thematically, tied into the work she was doing on Squeeze.

She also read Min Jin Lee’s celebrated 2017 novel, Pachinko, an epic tale about a Zainichi family, and was stunned at all the echoes of her own family’s story. Like several characters in the book, Ashworth’s grandfather owned pachinko parlors — a cornerstone of the Japanese gambling industry that Korean Japanese people came to dominate because they were so often shut out of other jobs — and it was this business that allowed her grandfather to raise his family out of extreme poverty.

Sasami in Los Angeles, December 2021

Daniel Topete for IndieLand

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“My family was always talking about pachinko machines, and I never knew what they were until I read this fictional book,” Ashworth says. “Family — these random people you probably wouldn’t even know if you weren’t related by DNA — is such an interesting source for storytelling. Everyone’s family is a weird snowflake, so it’s natural that going deep into your family’s history helps ignite some fantasy world.”

While Ashworth is still waiting to speak to her grandmother in person, her conversations with her mother have already opened up more, thanks to all she’s learned. That’s also shed some light on how and why her parents joined and raised her in the Unification Church, a Korean religious movement — often referred to as “the Moonies,” for the founder Sun Myung Moon — which some have labeled a cult.

Ashworth describes the Unification Church as a “Korean supremacist church,” and says for a young Zainichi woman like her mom, who barely felt like she belonged in her home country of Japan, finding such a welcoming group was a revelation, especially after she immigrated to America in her twenties, looking for a fresh start.

For Ashworth, who was raised in the very white L.A. suburb of El Segundo, the Unification Church rooted her childhood in Korean culture. She went to Korean school every Sunday and learned ritualistic prayers — but at the same time, the American faction of the church was, well, fairly Americanized and whitewashed. Nowhere was this more clear than the music.

“There were so many white hippies [in the church] and so much of the music was acoustic folk,” Ashworth recalls with a laugh. “We would sing ‘Eight Days a Week,’ but like, ‘Ooh, I need your love, Lord.’ That kind of shit. But there were also these beautiful acoustic folk songs, but with Korean melodies, and we would sing some traditional Korean folk songs, too.”

Ashworth is still unpacking it all — her time in the church, her family’s history, how some of these threads are tied, how others are not. But she doesn’t seem concerned with tidy answers. Emboldened by the search, she embraces the multitudes on Squeeze. It’s in the music, a newfound love of metal mingling with more classic rock and pop styles, and on the cover art, where the album’s title appears in Korean calligraphy by her mother.

“All your experiences give you emotional vocabulary for creating art, and growing up in a countercultural experience affects the lens with which you view your life and the world,” Ashworth says. “It’s hard to unravel what parts are from institutions, your family’s baggage, your own mental health issues, your environment. So much of making art is not questioning where the emotional experience necessarily comes from, but pulling the thread and going there.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});