‘She’s Not Free’: Inside Roger Waters’ Quest to Release a Jailed Kurdish Musician

Singer-songwriter Nûdem Durak was already two years into her 19-year prison sentence when one of the few threads that connected her to freedom was cut. Before her 2015 incarceration, Durak was living in Cizre, Turkey, singing songs in both Turkish and her ethnically native tongue, Kurdish. She was subsequently accused of communicating with members of the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers Party), which Turkey and the United States have called a terrorist organization. According to her lawyer, she was convicted of “membership in an illegal organization” and sentenced without being able to present evidence properly in her defense. When she reported for her sentence, she was allowed to bring her acoustic guitar to prison, but the instrument was ruined in a routine cell check in 2017 when guards severed its neck from the rest of its body.

“I always dreamed of having a guitar, but I didn’t have the money for it,” Durak recalled in an Al Jazeera interview before going to prison. “My mother gave me her wedding ring and said, ‘Sell this ring and buy a guitar.’ When I had the guitar, it meant the world to me.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2],[640,250]])

;

});

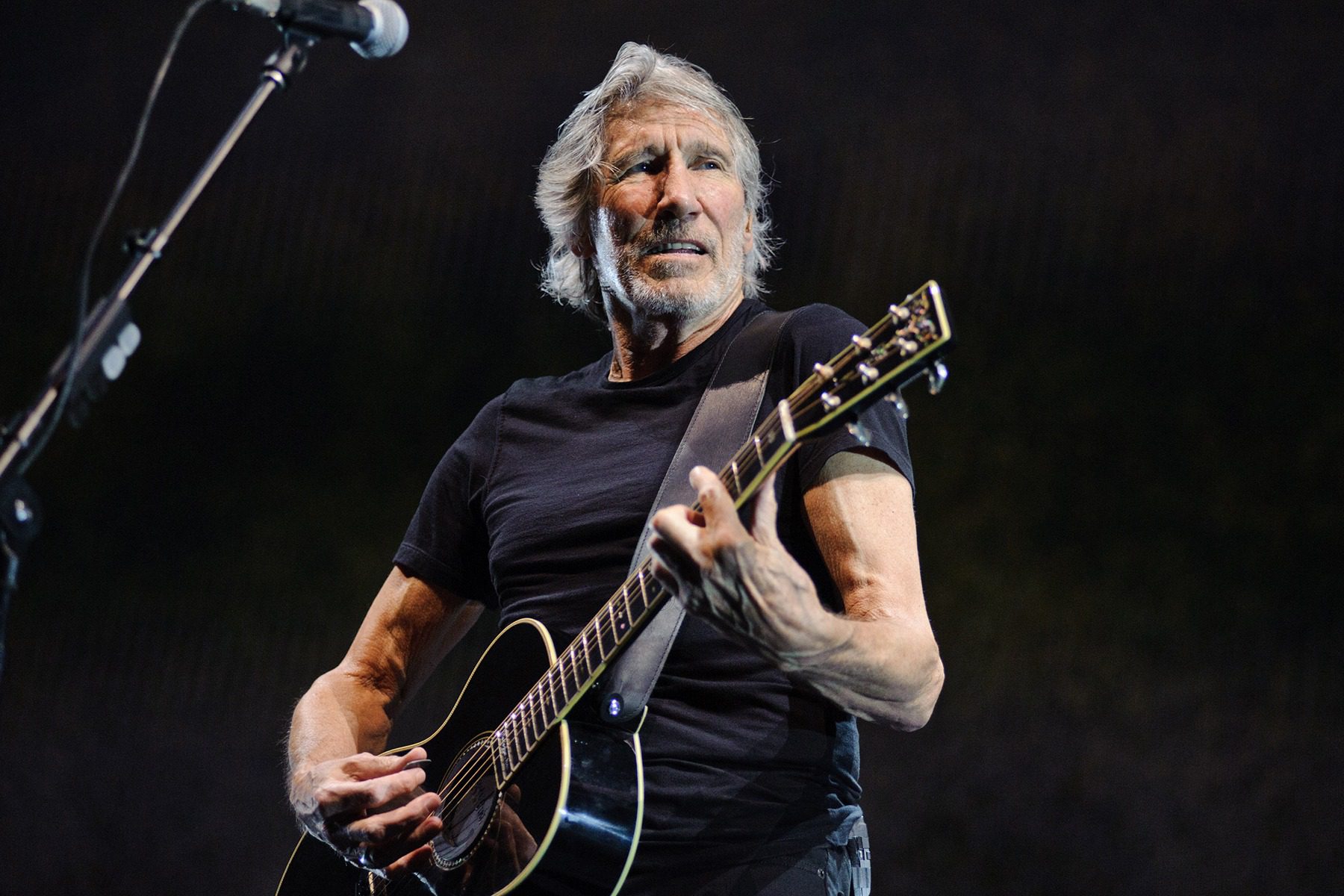

As awareness of Durak’s situation gained momentum in recent years, the destruction of her instrument has resonated with musicians around the world. Roger Waters, the solo artist and former Pink Floyd singer-songwriter, felt anger upon learning of her guitar’s fate and the nearly two-decade sentence she had received. “I imagine a guitar would be a comfort if you’re a singer-songwriter and you’re in prison,” he tells IndieLand. After doing extensive research into Durak’s case, he has been raising attention to her situation, enlisting rockers like Pete Townshend, Robert Plant, Peter Gabriel and Brian May to amplify her message and subsequently get her a new trial.

“Nûdem Durak is our sister,” Waters says, “and we have an absolute responsibility to support her and the hundreds of thousands of others who continue to suffer her fate with false imprisonment and incarceration all over the world, not least in the United States and the United Kingdom.”

“Art must be where our creative heart can be set free, whether it’s for the elevation of the human spirit or for our need for justice,” Townshend tells IndieLand in a statement. “Nûdem happens to be a Kurd. Her voice is connected to her soul and her soul will always sing for her family, her people, and her nation. As musicians, we can’t stop ourselves. Our truth is who we are and who we are born to be. It happens that Nûdem’s music is great music, and it is so saddening that a country with the immense historical artistic legacy of Turkey should treat a good musician the way they have treated Nûdem – whatever they feel about the Kurds’ desire for recognition.”

We will get you out #NûdemDurak pic.twitter.com/Fkjaj9g2hE

— Roger Waters (@rogerwaters) February 11, 2022

Waters subsequently came up with an attention-grabbing idea to bring eyes to her case: sending the black Martin acoustic guitar he used on his 2017/18 Us + Them Tour to Durak in prison but with a twist. Since the guitar began its travels from Waters’ home in Long Island, New York last year, it’s made several stops across Europe – where many of rock’s biggest names are endorsing the instrument with words of support – before heading to the Bayburt, Turkey prison housing Durak this year. “If we could move the Turkish authorities, that would be a very good thing,” he says. “Her lawyer told me through an interpreter that she said that she felt free for the first time in six years. She’s not free.”

In addition to Waters’ own signature, Townshend, Gabriel, Plant, May, Marianne Faithfull, Mark Knopfler, Noel Gallagher, and Waters’ onetime Pink Floyd bandmate, Nick Mason, have been adding their own inscriptions.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“I was made aware of the persecution of Kurdish musicians in the 1980s and more recently learned about Nûdem’s plight through my daughter who was working on the Voice Project,” Gabriel tells IndieLand, referring to the Voice Project’s “Imprisoned for Art” campaign in 2016. “The destruction of her guitar was something that any musician can identify with, so I was very pleased to be able to support her in this way.”

Waters’ views on Middle Eastern politics have rankled people around the world. His support of Palestine and the BDS movement in Israel’s West Bank, urging artists not to perform in Israel until the country grants equitable rights to Palestinians, have led to accusations of anti-semitism. “I am not an antisemite or against the Israeli people,” Waters said in response to an accusation from antisemitism watchdog group Community Security Trust. “I am a critic of the policies of the government of Israel.”

The Anti-Defamation League has also criticized Waters’ urging to boycott Israel in support of Palestine in letters to other musicians. In a response to criticism from Radiohead’s Thom Yorke over his views on Israel, Waters has said he believes that “the BDS picket line exists to shine a light on the predicament of the occupied people of Palestine.”

Before her arrest, Durak was a member of the musical group Koma Sorxwîn and also played music by herself at Cizre’s Mem û Zîn Cultural Center, which, until it was recently demolished, was a gathering place for Kurds in southeastern Turkey. That part of the country, along with neighboring areas of Iraq, Iran, and Syria, comprise the geo-cultural territory known as Kurdistan. Even though Kurds have lived there for centuries, they have faced oppression in recent years; from 1983 until 1991, it was illegal to speak Kurdish in Turkey and singing in Kurdish was a jailable offense.

By the time Durak was charged in 2015, Turkey had loosened its restrictions on the Kurdish culture while staying wary about PKK attacks. In the late Aughts, the country’s government reacted to these attacks with a police operation that led to the arrests of more than 150 people whom the government claimed were terrorists. With surveillance in the region ratcheted up, authorities accused Durak of making phone calls to PKK members and for visiting an address that turned out to be a PKK cell. (Turkey’s Ministry of Justice did not respond to multiple inquiries into the status of Durak’s sentence.) “She was imprisoned because she was falsely accused of being a danger to Turkish society, because they claim she was a terrorist or a terrorist sympathizer,” says Waters, who learned of Durak’s plight from a friend that directed him to the 2015 Al-Jazeera featurette on her.

“My lawyer called me and told me I have been sentenced,” Durak said in the clip. “There was an arrest warrant for me. I thought he was joking. I even laughed at him. Unfortunately, it was true. And it isn’t a few years of prison time; it’s 10-and-a-half years.” (The clip erroneously reports that Durak was sentenced simply for singing in prison, though her lawyer now says that wasn’t the case. Her sentence was later lengthened to 19 years.)

Kamilah Chavis*

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350],[2,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Durak’s lawyer, Ali Çimen, told Waters that she was not able to adequately defend herself, claiming that she was convicted, in part, on grounds that a wiretap recording was a “strong possibility” that it was her, but not confirmed. Çimen further claimed that Durak was unaware of any involvement with the PKK at the address she visited. Authorities told her that they had begun investigating her after she accepted a message from a PKK member while performing at the Mezopotamya Cultural Center, though the person who originally said she took the messages later recanted his accusation saying he was forced to give a false statement, according to Durak’s lawyer.

“It seems entirely clear that there is not a shred of evidence to support the government protestation that she’s a violent criminal,” Waters says. “There is no evidence to support that view at all. She’s done nothing except teach children to play the guitar and write and sing songs about her motherland. She’s a Kurd.”

In two trials, alongside more than a dozen other defendants each, Durak was sentenced to nine and 10 years, respectively, in connection to a terror attack that led to 18 deaths. Durak’s lawyer tells Waters that despite the fact that no one came forward with accusations against her, she was sentenced for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“It’s shocking to realize that there are still countries in which musicians who want to do exactly the same thing that we do end up in jail with their lives at risk,” Gabriel says. “It’s both a reminder of the freedoms we take for granted and the responsibility that we have to make their stories better known.”

Asked what the average person can do to help Durak, Waters says, “It’s a very good question. “There is a choir out there, and this choir will be deeply concerned about the predicament of this young woman, as they are concerned about the predicament of falsely imprisoned people, whether they’re political or not, everywhere. And that choir, from time to time, raises its voice in harmony.”