‘Strange Fruit’: The Timely Return of One of America’s Most Powerful Protest Songs

Last year, North Carolina rapper Rapsody was searching for an introductory track for her new album, Eve, a concept LP about the history and power of black women. Her producer suggested a song she didn’t know well: Nina Simone’s 1965 version of “Strange Fruit.” A concise but graphic evocation of a Southern lynching, “Strange Fruit” was one of America’s earliest and most shocking protest songs, drawing attention to the thousands of acts of racist terrorism against black people in this country’s history. “Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees/Pastoral scene of the gallant South/The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,” went one of its verses.

“As soon as I heard it, I knew that was the intro,” says Rapsody, who used the sample as the basis for her song “Nina.” “I’ve always been drawn to hearing about that part of our history, and I’ve been drawn to artists who speak to the reality of the times we live in. And even 80 years later, that song still speaks to the times. You don’t need more than 91 words. What else needs to be said?”

This year, with the return of Black Lives Matter protests to national headlines, a song written just over 80 years ago has taken on startling new relevance. In the first six months of this year, Billie Holiday’s 1939 recording of “Strange Fruit” — the first and most famous version of the song — was streamed more than 2 million times, according to Alpha Data, the data-analytics provider that powers the IndieLand Charts. On his SiriusXM show last month, Bruce Springsteen included “Strange Fruit” on his playlist of protest songs, and in an interview called it “just an epic piece of music that was so far ahead of its time. It still strikes a deep, deep, deep nerve in the conversation of today.”

Veteran R&B singer Bettye LaVette moved up the release of her new cover of “Strange Fruit” after the police killing of George Floyd. “I watch the news all day long, and the language started to change from ‘unarmed black man’ to ‘lynching,’” she told RS last month. “So I called the [record] company and told them that it seemed like we keep telling this story over and over and over.”

Director Lee Daniels will retell the song’s story in an upcoming movie, The United States Vs. Billie Holiday, just picked up for distribution by Paramount Pictures. Playing Holiday is Andra Day, known both for her inspirational R&B career. Three years ago, Day covered “Strange Fruit” in a rendition created to bring attention to the non-profit Equal Justice Initiative, which works to end mass incarceration. (Holiday will also be the subject of a new documentary, director James Erskine’s Billie, arriving in November.)

“‘Strange Fruit’ is still relevant, because black people are still being lynched,” says Day. “It’s not just a Southern breeze. That’s the polite version of it. We’re seeing that everywhere.”

The story of “Strange Fruit” is full of drama and surprises. As recounted in the work of author David Margolick (Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song), Joel Katz’s 2002 documentary Strange Fruit, and a study by scholar Nancy Kovaleff Baker, the song was first written by a white Jewish schoolteacher in the Bronx. Abel Meeropol, who taught English at DeWitt Clinton High School starting in 1927, was a dedicated Communist and progressive thinker who was also a part-time writer and poet.

Sometime in the Thirties, Meeropol came upon a photo of a lynching, most likely in a magazine. At the time, lynchings were shockingly commonplace: According to an updated study done last year by historians Charles Seguin and David Rigby, 4,467 people — 3,265 of them black — were lynched in America between 1883 and 1941. Photos of those horrific sites were turned into postcards (the line “They’re selling postcards of the hanging” in Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row” refers to the practice). The image Meeropol saw stayed with him and first appeared in a poem, “Bitter Fruit,” that he wrote for a 1937 union publication.

Meeropol, a self-taught composer and pianist with no musical training, soon set the poem to a spectral, meditative melody. The renamed “Strange Fruit” was performed on several occasions, including by singer Laura Duncan at Madison Square Garden, before it made its way to Holiday, who was then performing at New York’s Café Society club. Holiday didn’t just sing it; she inhabited it, earning her recording a place in history.

Holiday wasn’t immediately sure her audiences would want to hear the song. “I was scared people would hate it,” she wrote in her memoir, Lady Sings the Blues. “The first time I sang it I thought it was a mistake and I had been right being scared. There wasn’t even a patter of applause when I finished. Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everyone was clapping.” “Strange Fruit” became the centerpiece of Holiday’s set, often performed at the end of the show for maximum effect. As one critic wrote at the time, “The song is by far the most effective cry Miss Holiday’s race has uttered against the injustice of a Christian country.”

Fearing controversy, Holiday’s label, Columbia, opted out of recording the song, so Holiday turned to a smaller label, Commodore, and cut it in 1939. Between its sparse, unconventional arrangement and vivid lyrics, her recording of “Strange Fruit” became a sensation and a hit for Holiday when it was released by Commodore that year.

As music, “Strange Fruit” was hard to categorize. “Is it a blues song?” asks Meeropol’s son Robert. “It has a bluesy introduction, but it’s not rhythm and blues. It’s not blues. It’s not anything. It’s also unlike anything Abel ever wrote musically. I defy anyone to categorize the music.”

One undeniable fact, as Holiday wrote, was that the song took “all the strength out of me” when she sang it. Cassandra Wilson, who has recorded two versions of the song, the first in 1996, agrees: “The problem is not that it’s difficult to sing,” she says. “It’s emotionally draining. When we performed it live, we always did it as the last song. You can’t do anything else after that.”

Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” generated a range of reactions, positive to negative, appreciative to enraged. It also impacted Meeropol, who had published the song under his pseudonym Lewis Allan, based on the names of his and his wife Anne’s stillborn children. Shortly after Holiday’s version shook the music world, Meeropol testified before the New York state legislature’s Rapp-Coudert Committee, which was investigating supposed Communist influence in the state’s public schools and colleges. Robert Meeropol, who recalls that his father was asked whether the Communist Party had instructed him to write the song, says his father found the hearings “very amusing.”

Meeropol was surprised when, in her book, Holiday implied she had helped set his poem to music. This was untrue, according to the Meeropol family, but his father kept his complaints quiet: “He didn’t want to give the racists any ammunition against Billie Holiday, so he never publicly attacked her for falsely claiming his work.” At the urging of her book publisher, Holiday issued a statement that “Strange Fruit” was indeed “an original composition by Lewis Allan,” who was “the sole author.”

By 1953, Meeropol had relocated to Los Angeles to become a full-time songwriter; his other best-known composition was the anti-prejudice song “The House I Live In,” immortalized by Frank Sinatra. That year, Meeropol’s name returned to headlines when he and his wife adopted Robert and Michael — the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the couple executed by the U.S. government that year for supposedly passing American atom-bomb secrets to the Soviet Union. (Both Rosenbergs maintained their innocence.) Gossip columnist Walter Winchell, who’d taken a McCarthyite turn in that era, was among the many who stoked the fires of red-baiting rumor: “The Abe Meeropol who hid the Rosenberg children at his home and has a commy membership name (Lewis Allen) [sic] wrote the song ‘Strange Fruit,’” he groused in print.

Robert Meeropol, who was almost seven when he was adopted by the Meeropols, says he’s unclear whether his natural-born parents were familiar with “Strange Fruit.” In his memory, the Rosenbergs had no Holiday albums in their collection and didn’t go out to clubs much. But he says they referenced the song in one of their prison correspondences before their death. “It’s clear to me that they knew about it,” he says. “And given their politics, it would be surprising [if they hadn’t].”

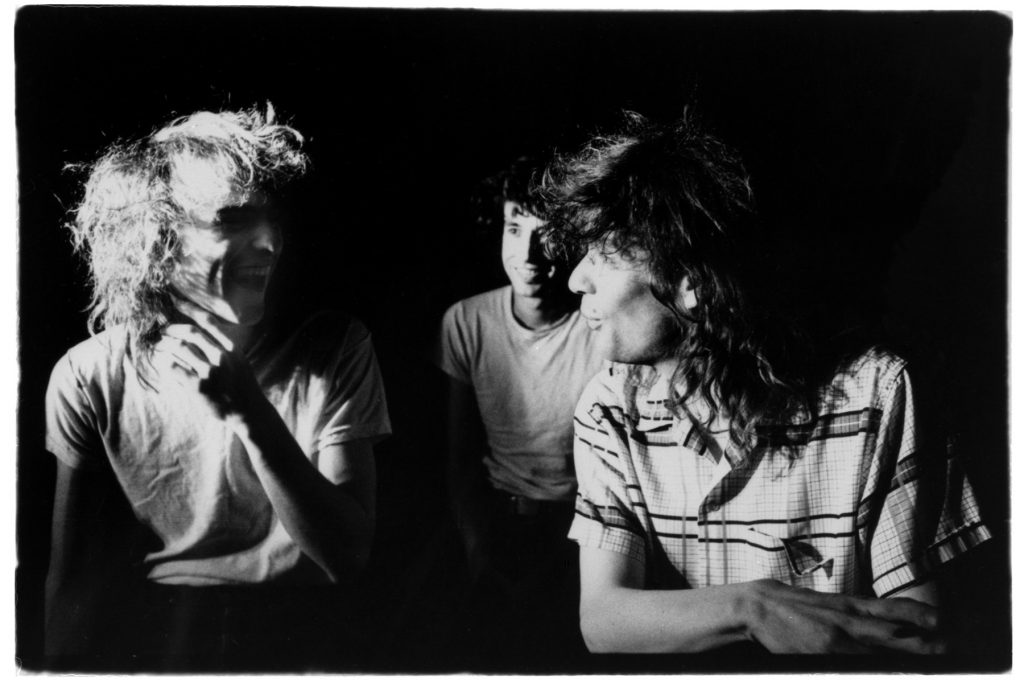

Nina Simone in 1964, the year before she recorded “Strange Fruit.”

Getty Images

Holiday kept singing the song through the years, but especially after her death in 1959, “Strange Fruit” took on a lower profile. Simone recorded her version in 1965, and Diana Ross sang it in her starring role as Holiday in the 1972 biopic Lady Sings the Blues. By the Seventies, though, Abel Meeropol was worried about the future of the song that made him most proud. As his son Robert recalls, “I remember him saying, ‘I wish I could help you boys out more. If it was played more, you’d get more royalties.’”

In 1980, a new version appeared when UB40 recast “Strange Fruit” to a reggae groove, and Meeropol’s friend Pete Seeger played him a tape of the song on a visit to the nursing home where Meeropol was suffering from Alzheimer’s. Still thinking his song was on the verge of being forgotten, Meeropol died at 83 in 1986; an old friend performed “Strange Fruit” at a memorial meeting at his house.

A few other covers emerged, like Siouxsie and the Banshees’ string-drenched 1987 cover; in the early Nineties, Tori Amos released a stripped-down version, and Jeff Buckley regularly included the song in his sets at the club Sin-é New York. Then, in 1996, Wilson included the song on her album New Moon Daughter, which focused on songs with Southern themes.

Wilson says she was inspired to include “Strange Fruit” for two reasons: Her mother had once told her about the time she had witnessed a lynching, and Wilson also connected the theme of slavery to music business practices. (Three years before, Prince had famously written the word “Slave” on his face to protest his treatment by Warner Brothers Records.) “Slavery is not just something in our past,” she says. “The music business has a lot of the same elements of it. So it could have been that I was forecasting something.”

New Moon Daughter went on to win a Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal performance, and Robert Meeropol feels that Wilson’s version helped reignite interest in the song. It has now been covered by more than 60 artists, including, recently, Annie Lennox, India.Arie, and Fantasia. The song’s emergence in hip-hop has been particularly striking. Over the last two decades, tracks like Cassidy’s “Celebration” and Pete Rock’s “Strange Fruit” have sampled it, along with Rapsody’s “Nina.”

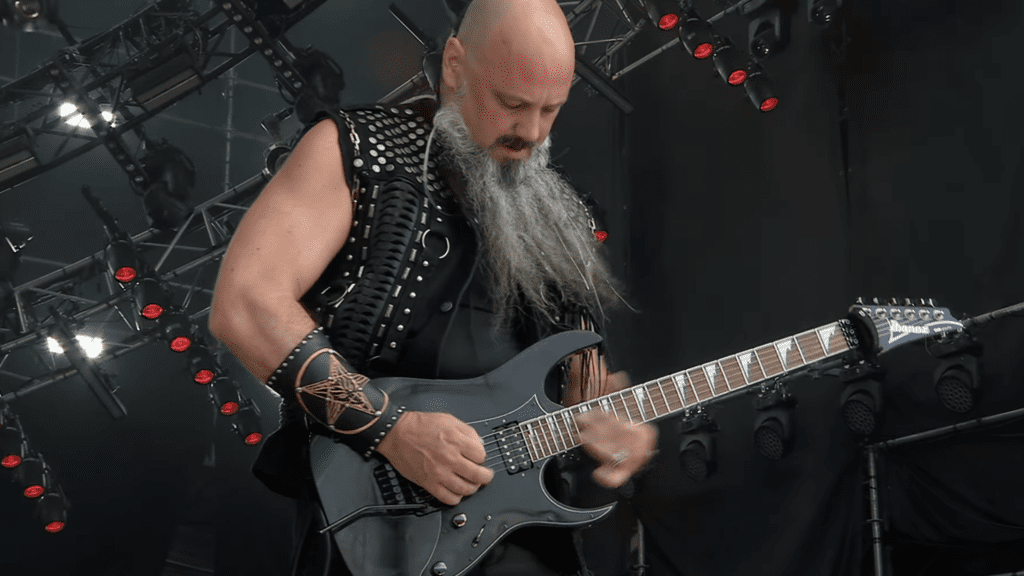

Kanye West, whose song “Blood on the Leaves” sampled Simone’s “Strange Fruit” in 2013.

Lloyd Bishop/NBCU Photo Bank/Getty Images

Rapsody feels that hip-hop artists are drawn to both the lyrics and the soulful singers, like Holiday and Simone, who sang “Strange Fruit.” Others have suggested that the political fury beneath the song’s chilled melody may be another reason it resonates today. “If the hip-hop generation is taking it to heart, they recognize it’s not mournful,” says Michael Meeropol. “Abel wasn’t mourning the deaths; he was calling out Southerners who were doing the murders.” Wilson agrees: “It’s a very angry song. ‘The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth.’ That’s pretty damn descriptive. How many lyrics do you hear like that?”

Seven years ago, Kanye West shone the brightest light on “Strange Fruit” when he incorporated a sample of Simone’s rendition in “Blood on the Leaves,” one of the most gripping moments on Yeezus. According to Elon Rutberg, the writer, director, and songwriter who was one of West’s collaborators on the song, “Blood on the Leaves” began as part of a discussion equating basketball players with modern slavery. “We thought that was very powerful,” he recalls. “It was the idea that people have everything but they don’t have the freedom they’re longing for.”

The result was a song narrated by an athlete tormented by professional and personal-life issues. “It’s this outrageous ask for the listener to connect with a wealthy person’s persona and private trauma, but it’s still connected to this larger struggle,” Rutberg adds. “‘Strange Fruit’ is about finding a way to articulate the feelings you have when you stare terror in the face, and we did not want to disrespect Nina or the original song.”

The Meeropols admits they were initially puzzled by West’s song: “Robby and I were like, ‘What’s going on here?’” recalls Michael. Adds his brother, “That started a discussion, and people were talking about Nina Simone and were starting to cover the song. Abel would not have minded that in the slightest.”

West’s “Blood on the Leaves” was streamed nearly four times as often as Holiday’s original in the first half of this year, according to Alpha Data. The Meeropols continue to earn royalties off the song: Thanks to several changes in copyright law, the lyrics and melody to “Strange Fruit” won’t go into public domain until 2033, 98 years after its initial 1939 copyright. The song has generated about $300,000 in royalties in just over the last 22 years. A portion of Robert Meeropol’s earnings has gone toward the establishment of the Abel Meeropol Social Justice Writing Awards; in 2017, the first recipient was black poet Patricia Smith, a multiple-time National Poetry Slam winner.

The fact that “Strange Fruit” is newly relevant is “a sad, sad commentary,” says Michael Meeropol. “We were supposed to have killed Jim Crow in 1964 and ’65. There’s a trope that says, ‘Until the last anti-Semite is dead, I’m Jewish.’ Now, until the last racist is dead, ‘Strange Fruit’ will be relevant. And the last racist is now president of the United States.”