Taylor Swift Has Been Working Toward ‘Folklore’ All Along

“I’m on some new shit,” Taylor Swift sings in the opening lines of Folklore, announcing with a smile and a wink that the many Taylor Swifts of her previous seven albums — even the not-quite-year-old Taylor of Lover — can’t come to the phone right now.

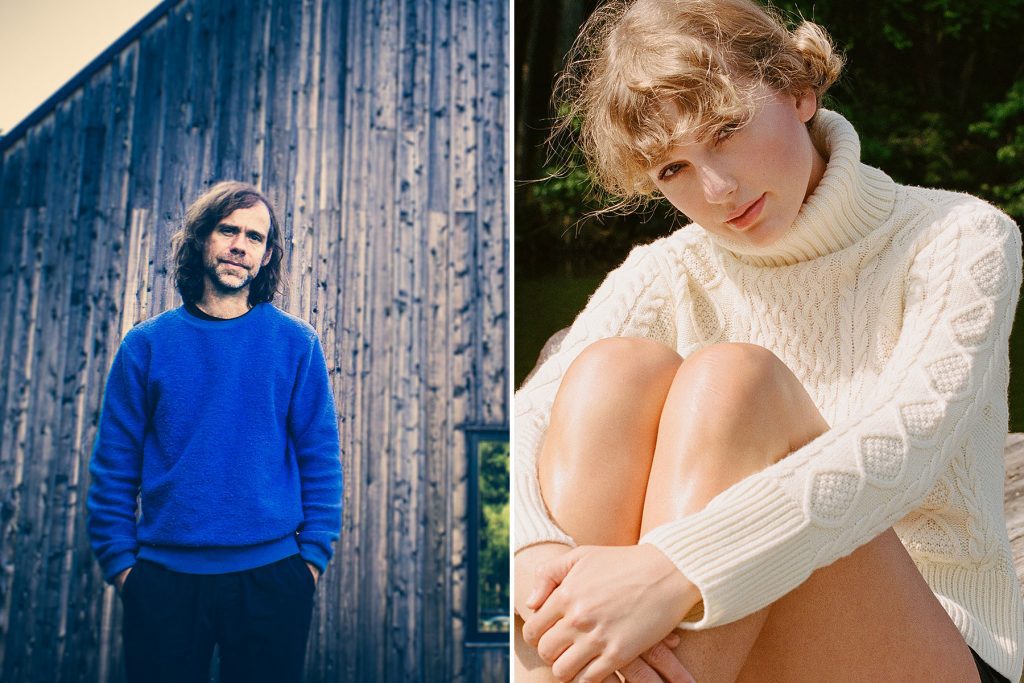

Swift has always conceived of herself, first and foremost, as a singer-songwriter. But she’s never presented herself to the world that way with quite so much clarity as on Folklore, the surprise LP that she spent the past four months recording with a who’s who of atmospheric indie rockers, including Aaron Dessner and Justin Vernon. The most surprising aspect of the album, though, is just how ultimately unsurprising it feels to hear Swift on her new shit, singing over fluttering High Violet trumpets, morose Dessner piano runs, and gently thundering 22, A Million programming glitches.

That’s because Swift has spent the past 15 years developing an internal world of melody and song structure so sui generis that her songs now belong more to her than to whatever sonic palette she’s working in at any given time. Take “Better Man,” the 2016 power ballad she wrote for country group Little Big Town, or “This is What You Came For,” the EDM hit she co-wrote for Rihanna that same year. Dressed up slightly differently, either song could have fit seamlessly on any of Swift’s last three albums — because at heart, neither of them is a country song or an EDM song, so much as they’re both Swift songs.

Swift could have chosen any number of directions for her latest step forward, but on Folklore she clearly relishes working in a realm that might be a little closer to the way she’s always heard her own songs in her head. “Just like a folk song/Our love will be passed on,” sings the woman named after James Taylor. Even if these songs don’t actually present as folk music in any strict musicological sense, it makes sense that Swift has chosen folk music as the broad aesthetic template for her deepest dive into writing third-person character sketches. “I found myself not only writing my own stories,” she said of her new album, “but also writing about or from the perspective of people i’ve never met.”

Like many who were melodramatic twenty-somethings in the late aughts, Swift has likely spent time with Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago, the album that redefined folk in the popular imagination a music of deeply felt cabin-in-the-woods seclusion. Faced, then, with an unfamiliar period of physical isolation under quarantine, Swift did what anyone in her position might: She called up Justin Vernon and started writing some sad songs.

Swift’s ability to effortlessly try on new sounds and styles comes from her lifetime of devouring every record she could get her hands on. As with all of her albums, there are hints of her wide-ranging listening all over Folklore: the Dashboard Confessional singles she obsessed over as a teenager; the light Avril Lavigne and Colbie Caillat singer-songwriter pop that helped inspire her first two albums; the Death Cab for Cutie, MGMT, Band of Horses, Tunnel of Love-era Springsteen, and Flaming Lips tunes she expressed love for on the Speak Now tour; and yes, the various National and Justin Vernon-related songs she’s been putting on her own curated playlists since as early as 2017. (In 2018, Swift shouted out the National’s “Slow Show,” which features the band’s all-time most Swiftian couplet: “You know I dreamed about you/For 29 years before I saw you.”)

As such, Folklore doesn’t signal any sort of declarative pivot from the past, so much as it opens up a new world of future costumes that’d surely fit her just as well, from pop-punk (as others showed on ReRed, last year’s scrappy garage-rock remake of 2012’s Red), to the spectral Ingrid Michaelson indie-pop she always seems one step away from diving into headfirst, to the dobro-laced Patty Griffin roots record Swift seems bound to one day gravitate towards a decade or two down the line.

There’s no question what genre any of those records would ultimately belong to — her own. But part of the fun of watching her genre-hopping is in the way she enjoys playfully embodying the outward aesthetics of her latest collaborators. In the case of Folklore, she’s been referring to newfound musical buddies like Vernon in public since at least 2014, and you can hear her taking up the role of a record-collector nerd even as she commands her own sound. On the chorus to “Cardigan,” Swift tries on her best version of Matt Berninger’s wine-tipsy “This is The Last Time” mumble, singing the word “I” as “i-i-i-i.” “Your favorite song was playing/from the far side of the gym,” she sighs later, alluding to the National’s 2017 song “Dark Side of the Gym,” one of Swift’s favorite of their tunes. (Leave it to Taylor to write a line about the fact that she placed a certain song on an Apple Music playlist.)

That line comes 14 songs into the album, on the Dessner-produced “Betty,” a rootsy, harmonica-driven number that, on one hand, feels like one of the precious few purely acoustic tunes you might expect from an album with a title like Folklore. On the other hand, the melody of “Betty” feels like an amalgamation of Swift’s entire balladeering career: the tender, “Tim McGraw” loping verse phrasing, the folk-pop Fearless pop turn in the chorus, the gently ascendant Speak Now bridge. “I showed up at your party,” Swift sings in the song, addressing, in part, any skeptical genre gatekeepers wondering what she’s doing with her newfangled sounds. But Swift has the last laugh once again. She knows she’s been at the party, lurking over on the dark side of the gym, the whole time.