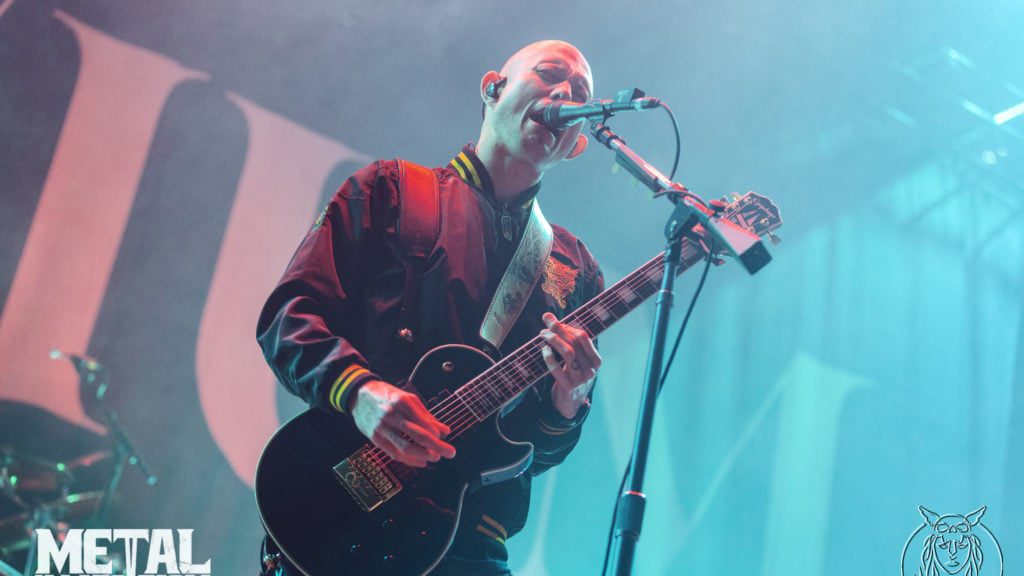

Teenage Disaster Is Making Good on His Dad’s Musical Dreams

Scott Baker grew up obsessed with all things horror, playing various types of heavy, riff-based music, and “listening to too much Danzig.” When he was 19, a band-mate took a demo to L.A. and claimed that it garnered some interest, but by the time Baker arrived, the deal had fallen through. He continued playing in groups anyway, including one with the son of Black Sabbath’s drummer Bill Ward. Ward “told me that one of the biggest regrets he had was that his son didn’t have a traditional childhood, growing up in hotels,” Baker recalled. This nugget stayed in his mind when he had his own son, Thorne, 20 years ago. “I couldn’t go out on the road and leave Thorne at home,” Baker says, so he quit the touring life. “When I was younger there were a million different things I put away to be a dad.”

Two decades later, he’s able to pick some of these activities up again thanks to Thorne, who records as Teenage Disaster, penning shambling, fuck-off rock, angsty guitar missiles, and ominous hip-hop, often from the perspective of threatening characters (killers, criminals, creeps, corpses, the usual). Teenage Disaster signed to Atlantic Records earlier this year. This is unusual considering that many record companies focus on signing music that is already popular on platforms like TikTok — the industry tends to reduce artists to hit singles and talks about those tracks with the same dispassion with which traders approach their stocks — but none of Teenage Disaster’s songs had even a million Spotify streams at the time of his signing.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

“Data forces you to rush and capture a moment,” says Jeff Levin, senior vice president of A&R at Atlantic Records. “I believe if you invest your time and energy on the art, the data will catch up. Building an artist’s world takes a lot of patience — most of the time, years.”

Thorne is from Humboldt County, California, known for its high-caliber marijuana, “but weed gives me panic attacks,” he says, “so there were no benefits to living there.” He grew up in a home stuffed to the gills with horror-movie paraphernalia (Scott: “We have life-size zombies and Frankenstein monsters in the dining room”), watched his dad practice guitar around the house (Thorne: “I was a dumb three year-old slapping bongos and screaming and shit”), and, as he grew older, became fixated on the videos from Rob Zombie’s Hellbilly Deluxe, watching them every day after school. Thorne attended a Montessori school that he liked about as much as panic attacks, but it did introduce him to the ukulele. “I would just play ukulele, add a fuck-ton of reverb to it, and make weird indie songs,” he remembers.

Scott, who was working at a gas station to pay the bills, didn’t believe the songs were quite so amateurish. “He had something that wasn’t just a kid screwing around,” the father says. “When I was his age, music was a sanity thing — you have shit in your head, and playing music is the best way to get it out. That’s what I saw him doing. I encouraged him as much as I could, got him microphones and guitars when I could, to keep him on that path.”

Discovering Lil Peep’s catalog was instrumental to Teenage Disaster’s development. “I found his music videos and fell in love with the aesthetic — emo, but it felt less cringe,” Thorne says. His friends didn’t care for it, but Thorne found Lil Peep tracks like “Crybaby” a call to arms: “It’s cool to be a musician on the internet!”

He kept writing songs and working on his production, posting snippets on Instagram, joining and then leaving a collective, finding other collaborators, changing his artist name, performing for initially uncaring crowds who were hoping for something closer to Youngboy Never Broke Again. At the same time, Thorne was struggling to stay afloat in school, battling depression and anxiety, frequently missing classes, and attending therapy on a weekly basis. “My dad was trying his best, single-handedly supporting me and my brother,” he says. “But growing up we were poor. We were fucking struggling. There were nights we couldn’t go grocery shopping. I’m punching the wall and shit, not being able to do anything.”

“We’ve been in survival mode forever, as long back as I can remember,” Scott acknowledges. “I never wanted my kids to go without. It’s been a constant struggle to provide them with the things they need, keep my head down, push forward, make ends meet.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

An inflection point arrived earlier this year when Liam McCarthy, a manager and talent scout, was hunting for new music on Spotify, scouring user-generated playlists on the platform in the hopes of striking gold. Buried in a collection titled “dark edgy rap songs,” he encountered Teenage Disaster’s “Criminal Song,” which pairs a nasty bass line with a series of nastier threats that rapidly escalate in intensity: “I’ll rob you, your mother, your sister, and your brother;” “I hate this place, I wanna punch yo’ face;” “Damn you could’ve run faster/Pray to the priest, but I killed the fuckin’ pastor.”

“It sounded different than everything in the playlist, which was mostly trap beats with fast hi-hats,” McCarthy recalls. He dug into Thorne’s other music. “He can make an intense rap song, or something like ‘Screwball,’ which reminded me of Dominic Fike,” McCarthy adds. “His versatility stood out. As did the creativity in the artwork, which he does himself, so it was all cohesive.”

Despite McCarthy’s enthusiasm, he initially had difficulty connecting with Thorne, who had stopped responding to people from the music industry that were reaching out to him on social media. “He had several people hitting him up to manage him, and some of those folks came off heavy-handed and creepy,” Scott explains. “So he was blowing them off.” Or, as Thorne puts it cheerfully, “I’m going through all my DMs like, ‘I hate these people!’” McCarthy managed to track down Scott’s landline to make contact, then flew up to Humboldt County over successive weekends to prove he wasn’t another one of the “heavy-handed, creepy” types; he now manages Thorne.

With help of a major-label budget, Thorne is now working excitedly on new music, and even better, videos, where his horror-filled upbringing can surely help him concoct eye-popping visuals. Scott is helping too — he quit the gas station job and already wrote one video treatment for Thorne. “I gave him the guitar part to an old song I wrote years and years ago and he made a song to it,” Scott says. “It’s cool to do music with my kid.”

To hear Thorne tell it, this is just the first of many collaborations. “I want him to get royalties from my stuff so he can support himself and my brother as well,” Thorne says. “And he can do the shit he was meant to do.”