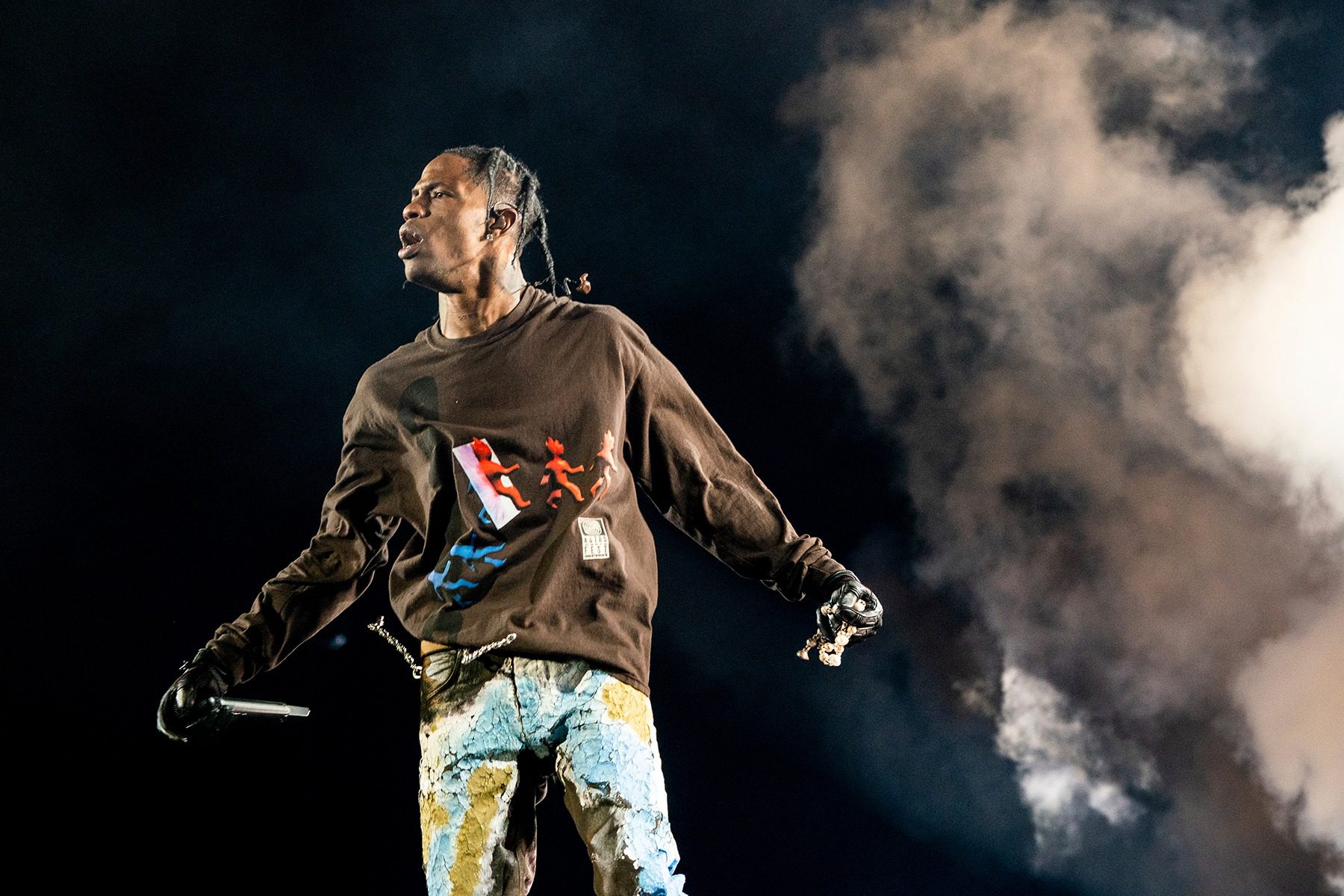

The Travis Scott Brand Wasn’t Built For This

For close to a decade, Travis Scott has carefully positioned himself squarely at the center of hype. His rise coincided with the corporate takeover of streetwear and sneaker cultures, making him a de facto stand-in for “cool.” An avatar on which to place as many logos as possible. His corporate partnerships, of which there are scores, have inspired fawning coverage in music magazines and business publications alike. Scott is, for better and for worse, a symbol of millennial marketing — easily adaptable, capable of molding himself around any company’s needs. The kids go crazy for it, regardless of what it is.

Except, it would appear that Scott has become too good at monetizing his audience; at turning the thousands of kids who’ll wait in line for a limited-edition sneaker, or a McDonald’s meal, into profit. It’s why, after eight people lost their lives and hundreds more were injured at Scott’s Astroworld Festival in Houston, the backlash was so swift. Up to now, Scott’s relationship with his audience, while far from symbiotic, hadn’t revealed itself to be parasitic. Sure, he’s a corporate behemoth in the form of a rapper, but he puts on a good show, and the shoes look cool. In a moment like this, however, that isn’t nearly enough to fall back on. The product Scott has become so adept at selling couldn’t be further removed from real life. From Cacti to his invocation of Houston’s iconic rodeo and even more iconic AstroWorld amusement park, Scott has never been in the business of real connection, instead gesturing at real-life references, sublimating any legible context to create an easily palatable product.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2],[640,250]])

;

});

Since news broke of the harrowing conditions in the crowd during Scott’s performance at his festival — of the fact that Scott continued performing for more than a half hour after officials had declared a “mass casualty event” — fans have taken to social media, calling on others to stop listening to Scott’s music on streaming services. In an instant, the audience he’s so consistently relied on for revenue turned on the Travis Scott enterprise. “Go to his Spotify page and click the … next to his name and ‘don’t play artist’ it will stop him from getting money,” has been copy-pasted by many users, followed by, “boost this.” (On the day of the tragedy at Astroworld, Scott’s “Escape Plan” received almost two million streams on Spotify, making it the number one song on the streaming service that day.)

Part of Scott’s appeal has been a mainstream repackaging of punk rock’s underground ethos. His concerts are notorious for aggressive mosh pits — which are often egged on by the rapper himself. Except, unlike the punk and hardcore scenes where mosh pits thrive, the “rage” Scott encourages at his show is ultimately hollow. It’s why many first-hand accounts of the events at Astroworld describe an audience seemingly unconcerned with humanity. In videos, you can see attendees dancing on top of ambulance trucks in the crowd. None of it seemed real, and why would it?

“I’m a huge fan of Travis but gawd DAMN he needa know when to chill tf out. I know he’s known for loving to ‘rage’ and thats cool n’ all but last night was completely outta control,” one fan tweeted. “He incites this shit on a regular so part of this is on him idc.”

On social media, upset fans have pointed to Scott’s previous shows — in which he allegedly encouraged people to jump from high-up balconies, and in one case was convicted of reckless endangerment for egging fans on at Lollapalooza — as proof that the rapper himself boosted the unsafe atmosphere that led to deaths at Astroworld. “He promotes people raging in the crowd,” tweeted one fan. “He cultivated this energy and should be held responsible.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Others have called him out for not stopping the show, despite the emergency that was unfolding. While he did pause briefly, some are arguing that other artists have taken more care in the past to deal with injured audience members, posting clips of bands like Linkin Park pausing their set when a show gets too rowdy.

But it isn’t surprising that Scott kept performing or, as has been reported, continued to encourage rowdy behavior well into his set. Travis Scott’s brand — his empire — never required him to be an actual person. It’s why, in the string of apologies the rapper posted since the tragedy unfolded, he can’t seem to strike a genuinely compassionate tone. Like an employer accused of wrongdoing, every response has the telltale markers of corporate damage control. In addition to covering funeral expenses for those who passed away at the festival, Scott announced a partnership with the app BetterHealth to offer free counseling for anyone traumatized by the experience. Even in the face of tragedy, Scott’s response is another corporate collaboration.

It reveals a fundamental flaw in the rapper’s multimillion-dollar brand. No one comes to Travis Scott for a deeply cultivated community of fans that care for one another. They come for hype. For the chance to get a pair of sneakers that’ll quadruple in value over the course of a few months. For a chance to be front-row at a social-media-worthy experience. After the tragic and avoidable events of Astroworld, it will be an almost impossible sell.

Additional reporting by Andrea Marks.