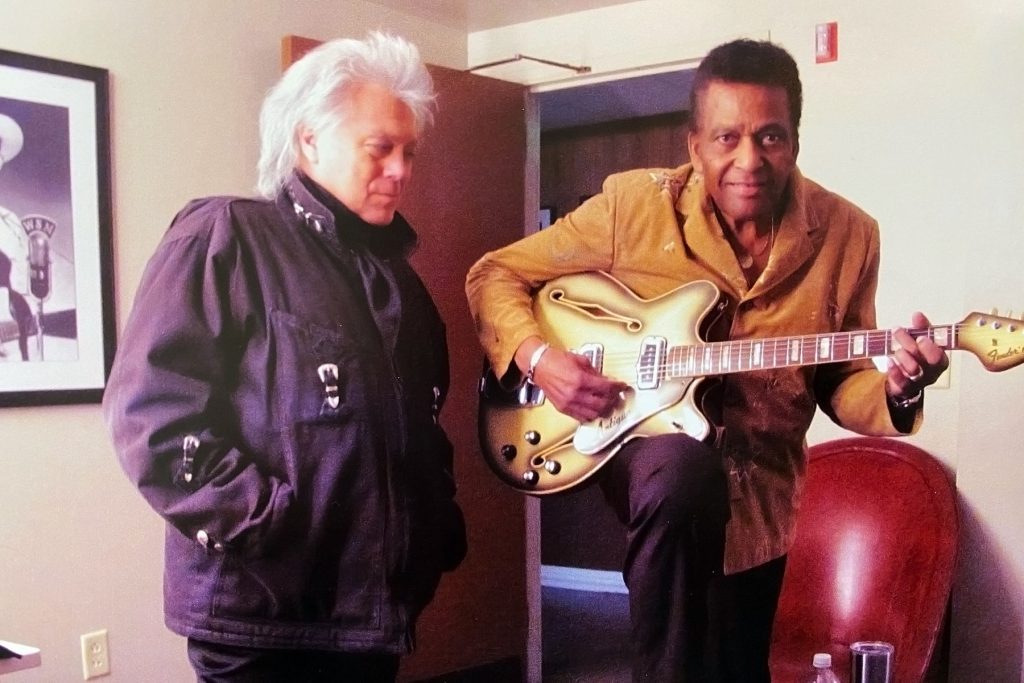

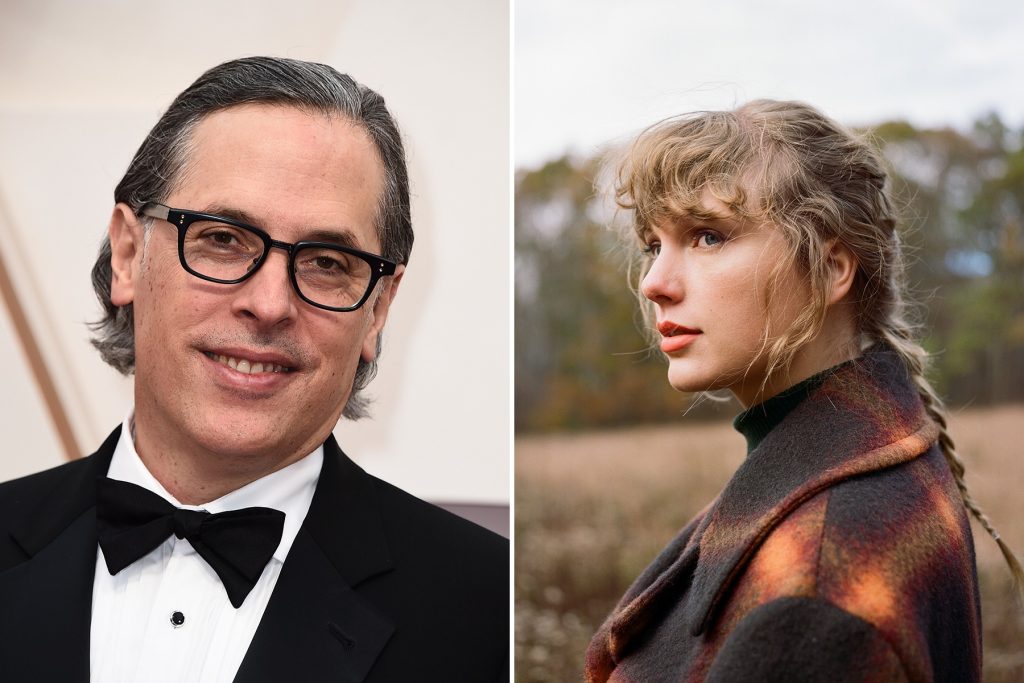

‘Willow’ Cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto Didn’t Know Taylor Swift Had a New Album, Either

When award-winning cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto started working on the video for “Willow” with Taylor Swift in November, he didn’t know that it was a part of her new surprise album, Evermore.

“I thought maybe it was a video for the previous album,” he tells IndieLand. “I didn’t even know what the song was at our first meeting.”

Prieto wasn’t the only one in the dark about the new record; Swift dropped Evermore last week with a very similar rollout to her previous LP Folklore, complete with a self-directed music video released at midnight along with the album: “Willow.” The video serves as a narrative continuation of the story in the “Cardigan” music video — which Prieto also worked on — featuring a ton of visual references to tracks from Folklore.

“Willow” starts off in the same cabin where the “Cardigan” video left off, and Swift is once again beckoned to go inside her magical, time-and-space-traveling piano. She follows a golden string (referencing the Folklore song “Invisible String”) and arrives at an autumnal forest clearing under a willow tree, where she sees the reflection of a man (played by her tour dancer Taeok Lee) and a woman in a moonlit pool. The string later leads her to a scene from her childhood, a carnival tent party where she performs inside a glass box, and a wintery seance in the middle of the forest. Eventually, the string leads her back to the cabin where she reunites with Lee.

As with the “Cardigan” video, Swift, Prieto and the production team not only had to keep the shoot under wraps, but also find innovative ways to film the project under Covid-19 safety protocols without endangering the lives of the crew. Prieto spoke to IndieLand about the production this time around, and how the team brought Swift’s witchy vision for “Willow” to life.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

How did the “Willow” shoot differ from “Cardigan”? It looks like you guys were able to have other actors on set this time around, but how did that change the safety measures you had to follow?

It was still very, very strict. A big part of it was the whole testing protocols, which we also did last time. But when we were doing this video, we knew more [about the virus], and the safety guidelines were more specific. We followed the same ones the DGA has done, that my union Local 600 has done, SAG — they’ve all put in place these protocols that we did follow, and were very careful about it.

For instance, in the scene with the choreography around the tree and the clearing, you know, with a sort of dance around these magical orbs, there was a limit on how many actors and dancers we could have there. That was created by visual effects, actually — they added in more dancers. I think the actual number was 10 dancers when we were filming, and they all have masks on, actually. We can’t see their faces, and that’s partly because they have masks.

There’s only really one moment, in the cabin, where she’s in close contact with [another actor], with the man that she’s been missing at all these different moments. But, of course, both were tested, and they’d only take off their masks in the moment where we’re actually shooting. Everyone else would always wear masks on. And similar to last time, anybody who was in the immediate vicinity of the scene had to have a red wristband — it was all color-coded, in terms of who could be close to the scene and the actors. And certainly, it was very important to have not only a mask, but a face shield whenever we were anywhere close to Taylor or any of the other actors or dancers.

I still used the remote camera on a crane, so there wasn’t even a camera operator close to anybody. We were still following all the guidelines very closely, but now, it felt more relaxed in the sense that we have more information. We could just follow all these protocols. And we knew that we’d be safe because it was all pretty strict.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

You mentioned last time that communication could sometimes be difficult on the “Cardigan” set because everyone had to kind of yell at each other or point to things since they couldn’t get in close proximity. Was Taylor able to be more hands-on in her directing this time around, like she was while you were shooting the music video for “The Man?”

That was still was the case — especially when you have a mask and a face shield, and you’re six feet away, you have to be a little louder to be heard. So we did maintain that protocol. But she was still very involved. I would stay at my monitor at the DIT [digital imaging technician] station, because it was the best image, but everyone would all be kind of looking at it from a distance, from six feet away.

But there was one moment that was unforgettable. And she actually has mentioned it, which was, just as we were starting to film on November 7th, we got the news of the election result. We were both looking at the monitor at the DIT station, and she got a text alert or something like that. Obviously, at that moment, we were all working on the video, but in the back of our minds we’re all like, OK, what’s gonna happen? And she was the only one who could actually look at her phone, because in fact, everybody had to relinquish their phones in the beginning so that nobody would take photos of anything, except for a few people like myself, who could sometimes use our phone to take a photograph as reference. And I was only using it very, very sporadically for that sort of thing.

So Taylor ended up being the messenger for the election results on set.

Exactly. So, she’s next to me — six feet away, but she was next to me. And she got this text, and she showed it to me. So I learned of the result from her at that moment, and what I told her was, “I will never forget this moment,” both because it’s such a historically important moment and because she was the one who showed me this information, you know. That was pretty special. Yeah. I felt like celebrating and doing a little dance, but I didn’t — we’re professionals and we’re working and also, I wanted to be respectful of anybody who had voted differently. But it was a very incredible moment, and just the beginning of a three-day shoot that turned out to be an adventure.

This video makes so many references to songs on Folklore and older songs from Taylor’s discography, both obvious and hidden. How did she lay out her vision to you?

The first meeting was talking about the story and the ideas. I still didn’t know the song, but the first thing was figuring out that it’s a continuation of the previous one we did together. At that moment, she was still kind of developing her ideas and trying to figure out exactly what was going to happen — for example, the ending wasn’t quite clear yet. She knew that she wanted to finish again in the cabin and that [the man] would be there, right. But during that meeting, we decided to have them both leave the cabin. That was an idea that came to us as we were talking as a team.

And then we went back and forth — at first she thought it should be night outside because it’s always been night, and then she changed her mind and said it should be daytime, so we were like, OK, what does it look like out there? Is it just the limbo? And then Ethan Tobman, our production designer, said it should be this sort of autumn forest. She was very much appreciative of that and really listened to everybody’s ideas.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

There was also discussion about that moment in the clearing, about whether it should be a bonfire or not. First of all, with production, we would have had to shoot it outside and that would have been very complicated. But also she felt that, even with special effects, it was not a good thing to show with all the wildfires going on in California. So she came up with the concept of some type of orbs, something more magical, and Ethan Tobman came up with a bunch of different reference photos for that. That was the way we developed these concepts — even with the willow tree, Ethan sent some images and ideas, and one of them had these magenta leaves on the ground, which was weird and magical. Taylor and I loved that. It was that kind of back-and-forth in the pre-production phase, before we even heard the music.

It’s amazing how you were able to pull this off under such complicated circumstances — communicating back-and-forth over Zoom, and then with the actual video shoot itself.

It’s pretty tricky to get such a complicated and really technically challenging shoot off the ground, but we planned it all beforehand. Ethan Tobman was working with his art director Simon Morgan on designing the sets over Zoom. So, it was all overhead plans, and then you have to go to the set and map it out. For that clearing scene, for instance, Simon Morgan and myself, and my gaffer Manny Tapia and my key grip Donald Reynolds, we went to the soundstage first and taped the space in the center where the magic orbs would be. And then we measured the distance to the background with the blue screen, and taped where all the trees would be, and then figured out where all the lighting would be for there and the carnival set — everything had to be very, very precise, and the distance had to all be worked out. It really helped when we were actually shooting, because it went very smoothly. So, that’s how we made it.