Hiroshi Yoshimura

In 1967, the Canadian composer and philosopher R. Murray Schafer wrote, “The ear is always open.” He didn’t mean metaphorically: Unlike the lidded eye, the ear cannot close itself off to unwanted stimuli, leaving us particularly susceptible to intrusive sounds. Schafer’s observation turned up again in the liner notes to Hiroshi Yoshimura’s debut album, 1982’s Music for Nine Postcards, a contemplative ambient soundtrack composed for Tokyo’s Hara Museum of Contemporary Art. Echoing Schafer’s preoccupation with the rising volume of the industrialized world, Satoshi Ashikawa, whose Sound Process label first released Yoshimura’s album, wrote, “Presently, the levels of sound and music in the environment have clearly exceeded man’s capacity to assimilate them, and the audio ecosystem is beginning to fall apart.” Encouraging a “more conscious attitude” toward sound, he offered Yoshimura’s music—delicate Rhodes figures trailing pastel shadows, their spiraling as aimless as a slowly twisting mobile in a large, empty room—as a kind of palliative.

Yoshimura, who died of cancer in 2003, was a polymath par excellence: composer, designer, historian. Most of his work existed in the overlap between sound, architecture, and everyday life, including installations and commissioned work for museums, hotels, runway shows, an aquarium, a sports stadium, the Tokyo and Kobe subway systems, and Osaka International Airport. Yoshimura’s activities made him one of the central figures of kankyō ongaku, or environmental music, a homegrown style that drew upon Erik Satie’s “furniture music” and Brian Eno’s ambient investigations, as well as centuries-old ritual traditions, to fashion a new kind of site-specific sound uniquely suited to Japan’s post-war economic boom.

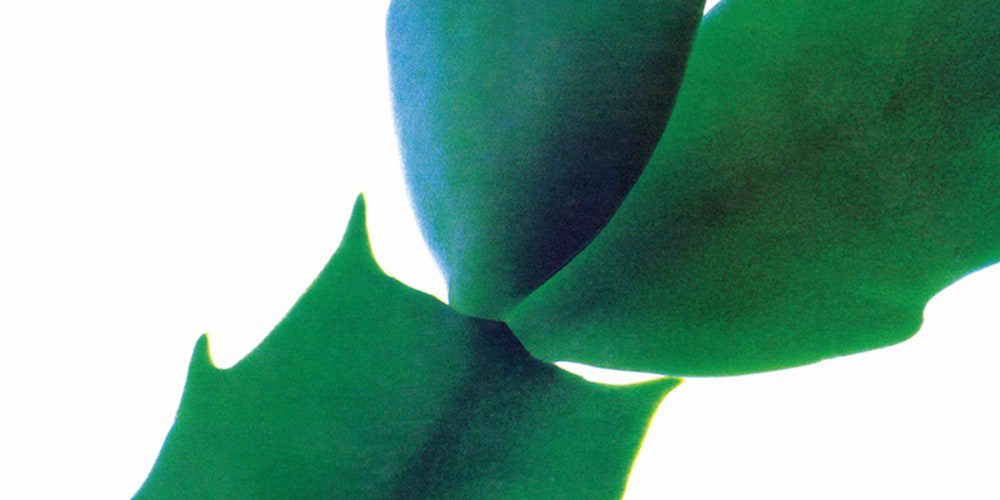

Yet listeners outside Japan remained largely ignorant of Yoshimura’s legacy until the past decade, when people like Spencer Doran, of the Portland, Oregon, duo Visible Cloaks, began advocating for his work. In 2017, Doran and Maxwell August Croy’s Empire of Signs label reissued Music for Nine Postcards, helping kick off what has become a broad revival of formerly obscure Japanese ambient and electronic music; Doran also curated Light in the Attic’s 2019 compilation Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990. GREEN, originally released on Kazuo Uehara’s AIR Records in 1986, is not just a welcome addition to that retrospective catalog; a cult classic of growing acclaim (a YouTube upload of the album has been played more than two million times in just four years), it is crucial in fleshing out the portrait of a musician that many Westerners are only beginning to understand.

Many of Yoshimura’s early releases were soundscapes designed to heighten listeners’ perceptions of the spaces around them. Music for Nine Postcards, written with the Hara Museum’s luminous interior in mind, was inspired by scenes glimpsed from the composer’s window—a kind of landscape drawing in sound, translating the movements of clouds and tree branches into simple, gestural motifs. In his notes to 1983’s Pier & Loft, the muted soundtrack to a fashion show held in a warehouse on the Tokyo Bay, Yoshimura wrote obliquely of nostalgic views of a disintegrating city. Cosmetics maker Shiseido commissioned 1984’s barely there A・I・R (Air in Resort) as the sonic complement to a fragrance, while 1986’s lulling Soundscape 1: Surround was distributed as the almost imperceptible soundtrack to a tastefully designed line of prefab homes.

All of these recordings share certain sonic characteristics: They tend to be soft, unobtrusive, and meditative, dissolving like sugar on the tongue. But GREEN is different: lush and layered, with a sense of purpose that makes it unique in Yoshimura’s catalog. The shift in complexity is palpable from the very first track, “CREEK,” in which mallet-like arpeggios rise from a thrumming, struck-bamboo pulse like a flock of colorful birds bursting from the rushes. It feels more elaborate than Yoshimura’s previous work; it feels more musical, with a greater emphasis on harmonic surprise.

This sense of movement ripples across the album, but it remains quietest at its center: The stretch of songs across “SLEEP, “GREEN,” “FEET,” and “STREET” reprises the abstracted mood of Music for Nine Postcards—an impression reinforced by the fact that “FEET” and “STREET” are essentially variations on a theme. Still, even at its most sedate, GREEN boasts an inviting array of timbres and textures. In one song, the gentle bite of an overdriven Rhodes keyboard jumps to the fore; in another, a buzzing FM bass tone bristles faintly. Yoshimura favors pentatonic scales and tends to avoid major or minor thirds, and as a result, GREEN often feels like an inviting frame in which to project your own feelings. Happy, sad, blue, agitated: It welcomes all comers, promises serene uplift when needed, and offers to sand the edge off any unwanted extremes.

Curiously, all of GREEN’s song titles share an assonant ee sound. The titles were written in English on the original sleeve, along with a cryptic acrostic descending down the musical stave: “Garden River Echo Empty Nostalgia/Ground Rain Earth Environment Nature.” In the liner notes to the original release, Yoshimura wrote, “GREEN does not specifically refer to a color. I like the word for its phonetic quality, and song titles were chosen for their similar linguistic characteristics. I hope that this music will convey the comfortable scenery of the natural cycle known as GREEN.” By treating “green” as a phoneme, Yoshimura taps into the musicality of language, which lies beyond mere signification. However anyone else might hear this music, Yoshimura clearly believed his pieces belonged to the key of ee, and developed an evocative synesthetic world to accompany his mental images of that sound.

If Satoshi Ashikawa saw Yoshimura’s work as a necessary corrective to the modern world’s persistent and worsening din, perhaps this is an opportune time to reconnect with the Japanese composer’s work. Numerous reports have detailed the ways that the world has quieted during the pandemic. With fewer cars on the road, seismologists can detect earthquakes from further away; even in the busiest cities, birdsong is once again audible. This pause opens up a space for Yoshimura’s music to fulfill its purpose: recalibrate our relationship with the sonic world around us.

When GREEN was licensed to the American new-age label Sona Gaia for release on CD and cassette, the sounds of running water and birdsong were added, presumably as a selling point for the American market. Light in the Attic’s reissue restores the original edition, which, Doran says, is the version that Yoshimura preferred. Light in the Attic plans to reissue the adulterated “SFX Version” on streaming platforms this summer, alongside the original; eventually, you can compare for yourself. For a long time, the Sona Gaia version was the only one I knew. But in the past couple of months, I’ve been listening to the Light in the Attic reissue, sans nature sounds, while sitting outside on my porch, where the music mingles with the actual sounds of birds, neighbors’ voices, and the breeze through the trees, plus the occasional motorcycle revving rudely, a few blocks away. These sounds turn out to be the perfect complements for Yoshimura’s music, opening up its dimensions. The ear is always open, and all the world’s a stage.

Buy: Rough Trade

(Pitchfork earns a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)