‘It was like a toxic relationship’: the exiled Russian musicians starting again abroad

‘We can say what we feel,” says Nadya Samodurova, “but we needed to move to another country to do so.” Half of the acclaimed Russian psych-rock band Lucidvox are speaking to me, via video link, from a modest room in the Serbian capital Belgrade. It’s where Samodurova and Anna Moskvitina, the group’s drummer and bassist, have moved to since the war against Ukraine began because, as Samodurova puts it: “It’s really dangerous to speak out in Russia.”

“I felt like I needed to move,” adds Moskvitina, “because I don’t want to pretend that I’m someone else.”

Their two bandmates, Alina Evseeva and Galla Gintovt, have also left, and are now based in Israel and Germany respectively. Like many of their musician friends, the ongoing conflict has made them exiles.

It is a dangerous time to be an outspoken Russian artist. In November, a court sentenced Aleksandra “Sasha” Skochilenko, a musician, artist and activist from St Petersburg, to seven years in prison for “knowingly spreading false information about the Russian army” in March 2022. Skochilenko had replaced five price tags in a local supermarket with pieces of paper urging shoppers to stop the war and resist propaganda on television.

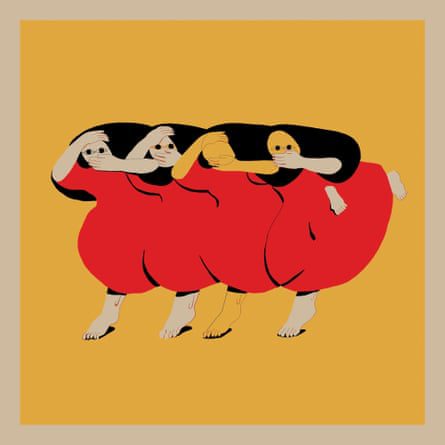

Since the war began in February 2022, the alternative Russian music scene has lost many of its leading players. Not only Lucidvox, who recently released their second album, That’s What Remained, to widespread praise, but also artists such as Gnoomes and Kate NV, who have all based themselves abroad, and see little prospect of returning. “It doesn’t seem possible in the near future,” says Moskvitina. “To be mentally stable, it’s better not to think about it.”

Evgeny Gorbunov is a musician, media artist, indie label owner and guitarist in the band Glintshake. His solo project Inturist blends avant-rock, psychedelia, kosmiche and off-kilter electronica. New album, Off-Season, is his sixth. “It’s ironic stuff about a long term vacation,” he says. “That feeling where you are a bit lost in a new place and don’t know what will happen next.”

Gorbunov now lives in Berlin, his third move since the war began, following spells in Slovenia and Tel Aviv. “The main reason is the war,” he says. “I don’t support the regime. You can go to jail for a long, long time just for posting something about the president.”

For Samodurova, whose day job is in the music industry, there were pragmatic reasons for leaving Russia as well as ideological ones. “I’m involved with a few showcase festivals in Moscow that bring artists from all over the world, and we realised that we can’t bring international artists to Moscow any more. Also, I didn’t want to go on stage and play with artists who support the war.”

Moskvitina emphasises that some musicians who have remained are also anti-war and anti-Putin. Their friends in the band Shortparis have chosen to stay in St Petersburg. “They are against the war but they want to stay and say something and support their friends,” she says. “Underground music has gone even more underground. These people are the bravest we know, because it’s not safe at all.”

This is no exaggeration. “You can say something [negative] on Instagram and go to prison for five years,” says Samodurova. “Day by day, people we know, activists, have this. People are really scared to say something on social networks because they don’t want to go to prison. The last protest I was at after the war started, it was really aggressive for people.”

There is also another risk. “The danger of being recruited into the military is real, but you have a choice,” says Gorbunov. “My friends would prefer jail to going to war.”

I speak to Gnoomes, now a duo consisting of Sasha Piankov and his wife Masha, while they are back in their home city of Perm, 1,200 km east of Moscow, finalising the paperwork that will allow them to relocate permanently to Slovenia, where Masha’s parents have a house. It’s an anxious time. “My parents just received a letter saying I am invited to the military office,” says Sasha. “That’s not the official summons, but it’s still scary. If I receive an official paper about the army, I don’t know how it’s going to be. We don’t feel safe here. Even inside our families, it is tricky to talk.”

Similarly, even in exile, Samodurova is “a little nervous, because I am doing a festival which creates some positive noise against the war, and also we have the band. I want to have the opportunity to go back to see my relatives. I could be nervous, but I don’t want to shut up.”

Gnoomes can’t wait to leave for good. “We wanted to do it for a long time,” says Masha. “The war was a kick in the ass. We were living in a bubble and Covid made it worse. We would destroy our career as musicians if we stayed here.” While in Perm, they take refuge in what Sasha calls “inner emigration”. In their heads, they are already gone.

Gnoomes’ situation highlights a divide. In Moscow, says Moskvitina, “in our environment, among artistic and creative people, I don’t know one person from our generation who supports Putin and the war. But Moscow is not Russia, you know? It’s a very European city, with lots of creative people. In the regions there could be other opinions because they have different lives.”

“It’s not like Moscow in Perm,” Masha confirms. “Here, you cannot find a bottle of Coca-Cola.” All the artists agree that older generations are much less likely to question official news channels and pro-Putin propaganda.

after newsletter promotion

Art can transcend borders, but despite being vocally resistant to the war, some Russian artists have been subject to negative reactions within the global music community. In October, British duo Giant Swan and Swiss-born Aïsha Devi, cancelled appearances at Serbian music festival Changeover because Russians were part of the organising team, which includes Samodurova. “Some artists cancelled because they had a lot of aggression from Ukrainian people,” says Samodurova. “But we have Ukrainian people working on the festival, and my colleague is on the list of people who are dangerous in Russia. He can’t go back. We made some posts explaining our views. I don’t want to answer with aggression. We do what we want to do, to help artists play music and share some feelings.”

She worries that it may affect the way people react to Lucidvox. “I saw a few [negative] comments on Facebook when we released the single. I have a fear that some people will not listen to the album but will just go to the comments and say, ‘Russians, fuck you!’ It’s really sad. Some people don’t know what is going on in Russia and how the government is really dangerous for people. Also, it’s hard for us to live a new life. We’ve had difficult conversations with our relatives. I heard some words from my father, like, ‘You’re not my daughter any more.’”

“When the war started, there was this mass hysteria about cancelling Russian culture, and I was confused,” says Gorbunov. “You want to be part of society, but you also understand that it’s not fair, because in the counterculture in Russia, most personalities oppose the repressive machine. The Russian government withheld funding for modern culture for many years, because it is not traditional. Art is an instrument of protest, so cancelling Russian culture is not really a smart decision.” Happily, he says, “I haven’t met one person who has judged me.”

Lucidvox’s album was mostly recorded in Moscow in 2020. The impact of the war has since made their creative lives much more complicated. “Before, we had very regular rehearsals, we would meet a lot and talk,” says Samodurova. “Now it’s much harder.”

“We didn’t see each other for a year,” says Moskvitina. “We met in Moscow a year ago, and we had one day of rehearsal! Hopefully, it should be easier now that Nadya and I live in the same city and can make music together.”

Along with the disruption, there has also been opportunity. New creative communities are forming, and there is a sense of excitement and regeneration. Belgrade is a hub for émigré Russian artists; one reason Gnoomes opted for Slovenia was because they are now only a five-hour drive from the Serbian capital. Originally, they considered moving to the UK on a global talent visa, but Brexit made it financially impossible to tour mainland Europe from Britain. “We’ve always felt safe in Europe,” says Masha.

Gorbunov has found maintaining his band Glintshake “complicated … our bass player has a son and a big family and he can’t break the connection [to Russia]. Our other members are scattered around the world. We didn’t have a rehearsal for more than a year.”

Yet with Inturist, he is making vibrant connections, including with a creative hub in the Italian city of Brescia. “I left Russia and I think now that I will be out for a long, long time,” he says. “It was like a toxic relationship – you normalise a lot of things that seem wild and crazy from the outside. I don’t really want to go back now. I want to integrate in other societies. There are a lot of people scattered around the world who make something on this niche level, and we understand each other. I feel like a fish in the ocean. Very excited.”