Pay to get playlisted? The accusations against Spotify’s Discovery Mode

In November 2020, Spotify published an opaque headline on its company blog: “Amplifying Artist Input in Your Personalised Recommendations.” The post introduced a new program called Discovery Mode, which would ask artists to accept lower royalty rates in exchange for algorithmic promotion. It was pay-to-play, but Spotify introduced the scheme using neutral language: artists would be able to “identify music that’s a priority for them”, which would become one of “thousands” of data inputs influencing how Spotify delivers “the perfect song for the moment, just for you”. Rather than charge an upfront fee, “labels or rights-holders agree to be paid a promotional recording royalty rate for streams in personalised listening sessions where Spotify provided this service”.

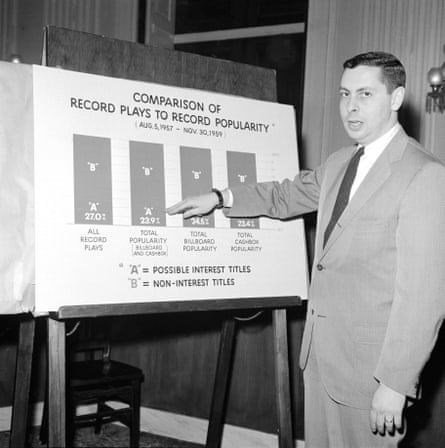

Participating artists and labels take a 30% royalty reduction on tracks enrolled in the program, when they are discovered through its channels. Only tracks more than 30 days old are eligible. Notably, there have been no signs that Spotify plans to publicly label which songs are enrolled: a lack of disclosure that has caused many music advocacy groups to liken Discovery Mode to the radio payola of the 1950s, which was eventually outlawed by the US Federal Trade Commission. (Though the company points out that it has published a broad guide to understanding recommendations on Spotify, including a paragraph on “commercial considerations”.)

In the early 1960s, in what became known as “the Payola hearings”, the US government outlawed the practice of radio stations accepting under-the-table cash in exchange for airplay without disclosure. According to several accounts of the day’s payola practices, sometimes DJs were handed stacks of cash, but other times they were offered fake songwriting credits or a percentage of royalties. And while making payola illegal did not automatically make mainstream radio more fair – some say that now there exists just an “institutionalised” form of payola – outlawing it sent a message about the responsibility of regulators to take corporate deception of the public seriously. Payola was outlawed, in part, because regulators said accepting money in exchange for plays could artificially inflate popularity and mislead listeners.

Spotify, of course, framed Discovery Mode – which wasn’t exactly replicating the terms of radio payola – as democratising. One Spotify employee explained it this way: “We’re not asking for any upfront budget or payment, which means there’s no barrier to entry.” More artists would now have the freedom to devalue their work, the opportunity to participate in an extractive system – and that was somehow democratic.

Discovery Mode’s inner workings are, in part, a product of how playlists have evolved more broadly. Many of Spotify’s recommendation systems start with a curator identifying songs eligible to be included in a playlist; a personalisation algorithm then decides which 50 end up on a user’s playlist based on what they are most likely to identify with. Similarly, in the automated mixes impacted by Discovery Mode – user-specific mixes and the Radio and Autoplay features – a sequencing algorithm re-ranks the tracks from a relevant pool before they are delivered, increasing their chance of being served to users, a source explained.

Internally, Discovery Mode’s success has been measured by the percentage of total artists who were onboarded, and how much cash this was saving Spotify. By 2023, Spotify employees celebrated an “exciting Discovery Mode milestone”, according to a review of company Slack messages. More than 50% of what Spotify calls Tier 2–3 artists – those with annual royalties of $50,000-500,000 – had tried Discovery Mode. “Last year we set out with an ambitious goal of getting to 30%,” an employee wrote. “Surpassing 50% felt beyond our wildest dreams and yet here we are. Congrats all!”

Spotify has made a lot of money from Discovery Mode, with profits also exceeding goals. Between May 2022 and May 2023, Discovery Mode had brought in €61.4m (£51m) in gross profit, according to a review of a chart shared internally. In May 2023 alone, it generated €6.6m (£5.5m) in gross profit – with nearly all of it coming from the independent and DIY sectors. It appeared from the breakdown in the chart that there was a direct connection between the musicians who were opting into Discovery Mode and those who already stood to be affected by the introduction of so-called “artist-centric” royalty policies, which as of 2024 have demonetised tracks with less than 1000 annual streams.

But in the long term, Discovery Mode also seemed like an economic arrangement that only the most moneyed labels could afford. “Discovery Mode is very insidious in that it doesn’t matter whether you do it or not, you’re affected by it,” one indie label employee told me. “If all of your competitors are using Discovery Mode and you’re not, your share is going to go down.”

Three years after the launch of Discovery Mode’s pilot version, an employee reflected on Slack about what its architects had accomplished: “It’s amazing to look back on our progress.”

The disingenuous promotional material emphasised how this program was all about what the artist wanted to promote. But by the end of 2023, that was in question, as Spotify introduced “Pre-Campaign Insights” or PCI, an algorithm that would tell an artist or label which tracks were most likely to stream well in a Discovery Mode campaign. It was rolled out for “managed service” Discovery Mode customers, as opposed to “self-service” customers – advertising industry terminology referring to whether a customer has a point-of-contact managing their campaign. For those eligible, the company claimed that the PCI algorithm would recommend, with roughly 85% accuracy, tracks “predicted to see a lift in streams” from a Discovery Mode campaign.

One independent record label manager said she had tried Discovery Mode campaigns for different artists on her indie rock label, but it was only the “folk-leaning artists” for whom it was most effective. “It serves passive listeners,” she told me. She reflected on how frustrating it was that opting into Discovery Mode actually did lead to increased streams for her artists; the fact that someone would hear a promoted track and not know that it was promoted raised ethical concerns. “This, unfortunately, is the way that the future looks for us. And we have zero control over it.”

Another independent label manager noted that despite seeing results from Discovery Mode, he was not sure yet what their royalty statements would look like. “It’s this vicious cycle where we’re losing revenue because of streaming. And then streaming is pushing these weird opportunities on us. And we need to take them in order to make up for that lost revenue. It sadly is so desperate, because the industry changes so consistently and we are constantly thinking of ways to keep up.”

Discovery Mode wasn’t Spotify’s first go at paid promo. Since 2019, it had been trying to get artists to pay for pop-up ads called “Marquees”, which cost 50 cents per click, or 55 cents if the artist wanted to target “lapsed, casual, or recently interested listeners”. An artist set a dollar amount for the campaign, which would then run for 10 days, or until the budget was spent. “Our distributor said, don’t use this, you are going to lose money,” one of the independent label managers told me. In 2023, Spotify introduced another, similar ad product called “Showcase”, a sponsored shelf that sat on the home page; those cost 40 cents per click, and lasted 14 days.

Later that year, Spotify launched an initiative called Campaign Kit, its attempt to get artists to not just purchase Marquee ads, Showcase shelves, or to trade royalties for algorithmic promotion, but to convince them that all of these tools worked best when purchased together. The last component of the kit was Spotify’s tool for submitting tracks for editorial playlist consideration. It’s as if the company were saying it’s not enough to buy ads, take a reduced royalty to use Discovery Mode, or pray at the altar of playlist pitching: artists must do all of these things.

In late 2023, a Showcase-related announcement hit the company Slack, detailing a high benchmark hit just two months after launch: over €1m (£833k) worth of ads booked. “We should all be very proud of this moment. As you go through the proverbial halls, don’t forget to pat your local Native Ads Showcase drivers on the back.”

after newsletter promotion

Spotify’s pitches to the independent music industry seemed to be working. But these ambitions to monetise musicians were seriously concerning to many. The Artist Rights Alliance, in a Rolling Stone op-ed published in April 2021, called Discovery Mode “payola” as well as “exploitative”, “unfair”, and a “money grab”, noting the potential for the royalty cut to be “so steep that working artists and independent labels cannot even afford to pay it, clearing the field for major record labels and pop megastars to swallow up even more of the streaming pie”. The group wrote that the biggest losers would be “working artists, independent labels, and above all music fans looking to expand and diversify their listening.”

In June 2021, the United States House Judiciary Committee sent a letter to Spotify co-founder Daniel Ek, warning that the feature could establish a “race to the bottom” where artists feel required to accept lower royalties in order to be heard. The letter asserted that “at a time when the global pandemic has devastated incomes for musicians and other performers, without a clear path back to pre-pandemic levels, any plan that could ultimately lead to further cut pay for working artists and ultimately potentially less consumer choice raises significant policy issues”.

The authors of the House Judiciary letter outlined a series of questions directly for Daniel Ek: Would the pilot become permanent? What safeguards would protect artists from Discovery Mode boosts potentially cancelling each other out? How would the “promotional” royalty rate be calculated and would it be the same for everyone? How could artists and labels measure the success of the program on their streams? And how would royalties be returned to artists if participating failed to increase streams?

Shortly after the Artist Rights Alliance op-ed was published, a staff member shared it in a Slack channel called “ethics-club”, where a group of Spotify employees would debate ethical issues of the streaming business. Some of these employees quickly agreed with the alliance’s assertion that Discovery Mode was payola-like. One said that the article nicely summed up his “raised eyebrows” from the meeting where he first learned about the program. “Controlling more of the listening experience via programming pretty clearly benefits us more than anybody else,” a different employee wrote. “That’s exactly why we have goals to increase programmed share.”

“This isn’t just like selling a banner ad somewhere. The boosted plays come at the cost of other artists,” said another. “And as the article correctly notes, the degenerate case is that artists stop benefitting at all from paying us.”

Even Spotify’s own employees could see that Discovery Mode was a deceptive practice as they debated the general lack of transparency, and the blurred boundaries between pay-for-play and “marketplace”.

According to Kevin Erickson, director of the Future of Music Coalition, there are important distinctions between payola on radio and what may appear to be its contemporary online equivalent. Payola has gone underground with radio, but comparable practices online are happening out in the open. Musicians are not paid at all when they’re played on US AM or FM radio, so there isn’t the same sort of commercial incentive to use payola. “There’s this whole other category of harm that happens on the digital side,” said Erickson.

In his view, many of the issues artists face in the streaming era, including what has been characterised as digital payola, are antitrust issues that both the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have the power to take on as unfair methods of competition (because they suppress wages and contribute to an anticompetitive market) and as deceptive practices (because people don’t know whether they’re listening to a song due to a curated recommendation or a business relationship). In addition, Erickson noted, the FTC could also contribute to a more equitable streaming landscape by investigating the major record label contracts that are currently locked up by NDAs – as well as any contracts digital service providers hold with aggregators and stock music providers.

As he puts it: “Unaccountable power is the problem wherever it pops up. It’s not about any particular technology. It’s concentrated, unaccountable private power.”

In response to points raised in this article, a Spotify spokesperson disputed the characterisation of Discovery Mode as the contemporary equivalent of payola. While users cannot see which individual songs are part of Discovery Mode, the “about recommendations” link in algorithmically generated playlists discloses factors that may have influenced the tracklisting. Spotify disputes the accuracy of views shared by employees in some internal messages featured in this chapter. According to the company, these internal messages “appear to be largely from former employees who were chatting with each other about their views on different company matters, including matters that they may not have been working on or even have direct knowledge of”. The company adds: “We have a culture where employees are free to share their views even when they have concerns or constructive criticism.” They also dispute the claim that Discovery Mode is anticompetitive. The company would not comment on whether the Discovery Mode profits were accurate.