Anjimile’s Joyful Becoming

Anjimile Chithambo has always tried to do right by his students. The Boston-based singer-songwriter teaches after-school music classes for kids in kindergarten through fifth grade, and amid games of musical chairs and craft projects involving homemade instruments, he’s tried to mold their young minds by playing artists ranging from Madonna to Sufjan Stevens. Just one problem: The youths aren’t having any of it.

“The kids were like, ‘What the hell is this!? We don’t want to listen to Madonna!’” Chithambo recalls with a laugh. “I was like, ‘Come on!’ It made me realize how old I am.”

Chithambo, 27, isn’t that old (even if working with kids younger than Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face” is enough to make anyone feel ancient). Beyond the classroom, though, as he prepares to release his debut album as Anjimile, Giver Taker, on the scrappy indie label Father/Daughter Records, there’s something to that assessment. In the perennial search for what’s next in music, we often turn to the youngest voices; there’s something intriguing about an artist like Anjimile, who arrives with a few extra years of life and experience behind him.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

Anjimile wrote and refined the songs on Giver Taker over the past six years, as he got sober and began living more fully as a trans non-binary person (Anjimile uses both he/him and they/them pronouns). It’s very much a document of those years, formed in those dual crucibles, along with a molten mire of identity, love, grief, spirituality, family, failure, and possibility. There’s an element of reflection in the way the songs have transformed in that time, from the stripped-back versions on previous projects like 2018’s Colors and the 2019 Maker Mixtape, to the rich, textured compositions on Giver Taker.

Those earlier, self-released projects came while Anjimile was establishing his voice, living and gigging around Boston. In 2018, he entered NPR Music’s Tiny Desk Concert contest, and a panel from Boston affiliate WBUR named him the best entrant from Massachusetts. The following year, a Live Arts Boston grant from a pair of local non-profit foundations gave him the budget to make Giver Taker. Anjimile says his goal this time was to find a label that could help bring his music to an audience beyond Boston.

“It’s exciting, because they’ve been developing on their own in a scene for the past decade, and we get to come in and help bring them to a national — and hopefully international — audience,” says Tyler Andere, the A&R at Father/Daughter who signed Anjimile last year. “Anjimile is definitely one of the most seasoned artists that I’ve worked with, and it’s really important for them to be as involved on the business side of things, in all the conversations and on all the emails, as it is to be working on the music.”

Anjimile made Giver Taker with longtime bandmate Justine Bowe (who also fronts the synth-pop outfit Photocomfort) and New York-based indie artist/producer Gabe Goodman. Starting in March 2019, the three would leave their day jobs behind and spend one weekend a month in studios across Brooklyn, Boston, and New Hampshire, “getting the musical energy flowing,” as Anjimile puts it. Before this, Anjimile’s sound consisted of voice, guitar, occasional drums and bass, some scattered synths, and whatever other noises he could cook up on Ableton. He never imagined his songs could sound the way they do on Giver Taker, and he admits he was wary at first. When Goodman and Bowe first tied a synth harp solo onto the end of the first verse of album-opener “Your Tree,” Anjimile says he wondered, “What the hell are they doing to my song?” Twenty minutes later, he was firmly on the side of, “This is really, really dope.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

“They completely opened my musical heart and brain to a variety of new influences,” Anjimile says of his collaborators. “I feel like they were able to transform these songs and adorn them with gold and flowers and ribbons and frankincense and myrrh and shit like that.”

There’s perhaps no better example of this overhaul than lead single “Maker,” a song on which he carves a winding path towards self-actualization: “I’m not a just a boy, I’m a man/I’m not just a man, I’m a god/I’m not just a god, I’m a maker.” The version that first arrived in 2019 was a five-minute stunner built around Anjimile’s steely finger-picking. The album version of “Maker” starts similarly, only this time, the song unfolds with a percussive pulse, like rain drops on wood, followed by thick bass kicks, a skip-shuffle of drums into a new groove, a muted high-wire pluck of electric guitar, and then another sound — two bright stabs followed by an elated tumble that seems conjured from some unknown instrument Anjimile could’ve made with his music students.

Asked later about the source of this sound, Anjimile texts back gleefully: “It’s the sweet sweet guitar tone of Gabe Goodman,” followed by a requisite bursting-heart-eyes emoji. “He’s a wizard Harry!!”

Giver Taker is a record with no small amount of gravity — in its subject matter, musical palette, and especially in Anjimile’s voice: “This really brilliant, piercing vocal that cuts through the noise,” as Andere describes it. But Anjimile brings plenty of bliss, too. The instrumentation can be playful and grand; Anjimile’s lyrics flush with colors, natural wonders, literary nods, and sly quips. His voice can tenderize your heart as it does on a song like “1978,” but then he’ll turn around and sound positively rakish on “Baby No More.” The glue is a generosity of spirit and fearlessness, epitomized by the opening lines of “Ndimakukonda”: “Your parents think I’m crazy, I can’t say they’re wrong/I’m something of a soldier, marching into song.”

Anjimile’s parents emigrated from Malawi to the United States in the Eighties, and in the Nineties they settled in Richardson, Texas, a Dallas suburb flush with tech jobs known as the Telecom Corridor. His father was a doctor, his mother a computer programmer, and Anjimile the third of four kids. Anjimile is frank about his hometown — “pretty racist, pretty homophobic” — and how its structures of white supremacy became clearer as he grew older. At home, he says, “the love and comfort of the family unit helped to make that less painful.”

On Saturday mornings, 9 a.m. sharp, Anjimile’s mother would wake everyone up for breakfast and chores, clapping as she went from room to room, loud music blaring through the house. His parents’ rotation included Madonna, Michael Jackson, Bob Marley, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and the great Zimbabwean musician Oliver Mtukudzi. Outside the house, Anjimile sang choir and a cappella, went through punk and ska phases, and listened obsessively to Lauryn Hill and the Fugees. In 11th grade, a friend gave him a mixtape. “This is indie rock,” Anjimile remembers her saying with a laugh. “I think that person was the first hipster I’d ever seen.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The mix introduced Anjimile to Sufjan Stevens, Born Ruffians, and Iron and Wine, artists whose influence is central to Giver Taker, especially Anjimile’s guitar playing. He began playing at 10 or 12, but found using a pick to be uncomfortable; after he shifted to finger-picking, he refined his approach by playing along to Iron and Wine’s 2004 album, Our Endless Numbered Days. “It gave me the idea that I could play guitar in a way that worked for me,” he says. The picking patterns he absorbed from that record are laced throughout Giver Taker, as are alluring melodies gleaned from his parents’ Eighties pop favorites, and African polyrhythms plucked from Mtukudzi and Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Anjimile wrote his first songs in the summer of 2011 as he prepared to leave Texas for Boston to start college at Northeastern, a move spurred in part by a high school love of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe. In Boston, he started playing on-campus open mics, just him and his guitar; as he ventured deeper into the scene, playing house shows and bars, he tried out a full-band sound, too. Regular gigging and a handful of early recordings earned Anjimile some local renown, but by 2016, his future looked like it might be swallowed up by booze.

“I had stopped playing shows, I wasn’t really writing, because I was very busy drinking alcohol,” Anjimile says. “I think I decided I was quitting music to focus on drinking. There was no creativity happening. I had a lot of shame and guilt that created an emotional, psychological, and spiritual block, but also a creative block.”

Anjimile left Boston for Florida to seek treatment for alcoholism that year. Despite the creative wall he’d hit, he got on the plane with his guitar. “I bring that thing everywhere,” he says. “I kind of figured, if I were to stick it out, my instinct is to write songs. That’s just what I do.”

The songs didn’t come immediately, but when they did, about a month or two in, they “came rushing like a waterfall,” Anjimile says. One was “1978,” written for his maternal grandmother, who died in an accident long before Anjimile was born, but lived on in the strength and spirituality Anjimile saw in his mother. As he got sober, a conversation he’d had with his mom laid heavy in his mind. He was 18 or 19, and she’d sat him down and told him his grandfather had been an alcoholic, and his grandmother had suffered greatly because of it.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“This runs in the family,” Anjimile remembers his mother saying, “and she was an incredibly strong person. This is something that is part of our family history, and that you can face and overcome.”

“Being in recovery and getting sober completely transformed my life in an almost preposterously positive way.”

At the time, Anjimile acknowledges, he didn’t think much of that conversation; he wasn’t interested in getting sober, or ready to try. But in Florida, he says, “I started to view my grandmother as a driving force in my recovery and some ancestral strength that I could rely on and draw from. I just needed that strength. So I wrote [‘1978’] as a devotional, a dedication, and a thank you.”

Towards the end of his time in Florida, Anjimile wrote Giver Taker‘s closing track, “To Meet You There,” a musical exclamation point that ventures from euphoric folk to a deep house breakdown, then re-emerges even more elated than before. It’s the manifestation of the first joy Anjimile says he felt in years.

”Being in recovery and getting sober completely transformed my life in an almost preposterously positive way,” he says. “I was pretty convinced I was just going to die an alcoholic. I was not successful in trying to seek help, so when I actually was able to, I was like, ‘Holy shit, this is dope as fuck.’”

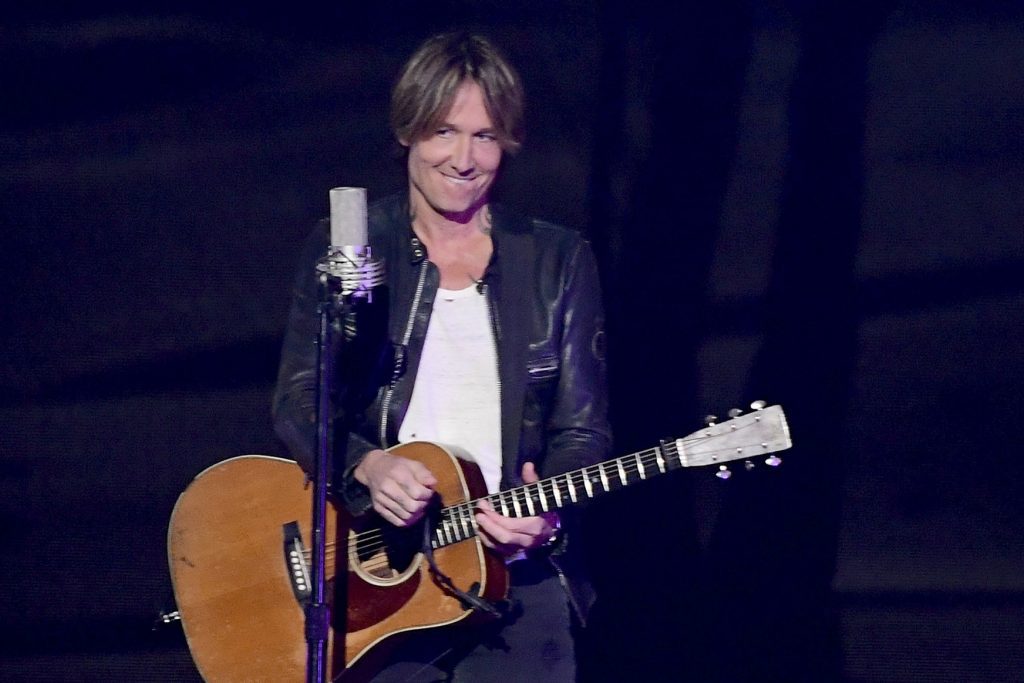

Kannetha Brown for IndieLand

Though much of Giver Taker came about during and after Anjimile’s time in recovery, there are a few songs that pre-date his sobriety. “Baby No More,” a slinky bit of folk-pop, finds him facing a relationship that’s floundering in no small part because of his drinking. Another example, somewhat surprisingly, is the clear-eyed “Maker.” Anjimile admits his memory is too fuzzy to recall the specifics of its creation, but he says it came from an attempt to buck himself up, spur some kind of change, and face himself in the mirror at a time of deep turmoil.

“My emotional health was on the decline and I wasn’t really doing anything to help that, and this was also coinciding with my realization that I was transgender,” he says.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The movement in the chorus — boy to man, man to god, god to maker — “I don’t know where the fuck that came from, but when it was written I felt it strongly to be true,” he continues. “I very much link my queer identity to my spirituality, and I think that’s where the progression came from. The boy to man thing, for me, was a movement of maturity. Man to god represented a transcendence from the idea of gender as an identity to my spiritual being as the thing that’s most important. And then…”

Anjimile stops suddenly. Then lets out a magnificent laugh. “I’m sorry,” he says after a moment. “I feel like I sound like a hippie.”

This is the exact tone that gives Giver Taker its power. It’s a deeply spiritual record — unabashedly holistic music for chaotic times. Spirituality, for Anjimile, is “deep, honest feeling,” and the vulnerability required to project that isn’t insignificant. The same goes for anyone who wants to receive it as a listener, to say nothing of the sincerity required all around. Getting that open, that earnest, is a lot, but maybe, as Anjimile does, you’re supposed to laugh. Not as a defense mechanism, but because deep, honest feeling is beautiful, and beauty brings joy.

As for that final leap in “Maker,” from god to maker, Anjimile explains: “At that period in my life, the only good thing I was doing, the only positive impact I was having was sometimes writing songs that were good. I was looking to being a maker, and to my creativity, as a lifeline.”

Anjimile was raised Presbyterian, spent his rebellious teenage years as a self-described atheist, but began seeking more explicit forms of spirituality after getting sober. He wanted to probe his place in the universe and also just “give props to it” after staring down death. His connection to nature and music deepened; he did indeed, as he happily admits, become a hippie. And his credo, no joke whatsoever, became Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz’s “Colors of the Wind,” from the 1995 Disney movie Pocahontas.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t really think much of the lyrics,” he says. “I was like, ‘This song’s tight, I’m loving these visuals, very colorful.’ And then as I got older, I started to seriously vibe with the lyrics. Just the concept of singing with all the voices of the mountains — there’s so much beautiful imagery in that song, and I can relate to that specific image as a vocalist. My voice is also part of my spirituality, because the way I feel when I sing is just so… I feel joy, and deep melancholy, and there’s just a lot of emotion, but it feels powerful.”

A year or so before recording Giver Taker, Anjimile began taking testosterone as he started to transition. He wanted his voice to change, but he knew that would mean learning to sing all over again. It was a difficult experience, but exciting as well. His upper register disappeared, and he gained a fragile falsetto that he found a bit embarrassing at first, but eventually came to realize was “powerful because of its fragility.” When it came time to record some of his older songs for Giver Taker, he found new textures and spaces to explore, even if it was just a simple hum on “To Meet You There.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“That ‘mmm’ sound just resonates in my chest now in a different way, because it’s a different note,” Anjimile says. “The sound of my singing voice has become so full and cavernous. It’s different, but I really like it, and I’m glad that’s happened.”

To make Giver Taker, Anjimile had to tap back into the original emotions that spurred these songs. “So many just feel so much truer than they did before,” he says. He cites the oldest song on the album, “Ndimakukonda,” a love song written in 2013 that pulls a bit of Shakespeare — the letter Hamlet writes Ophelia, “Doubt thou the stars are fire/Doubt that the sun doth move/Doubt truth to be a liar/But never doubt I love” — and takes its title and refrain from his parents’ language: “Ndimakukonda,” meaning “I love you” in Chichewa.

The song began, Anjimile says, as a love song to a former partner, but “now feels like a song of love to myself and my friends — and not just like a romantic overture, but an offering of love.”

Giver Taker arrives at a moment where Anjimile won’t be able to take his songs on the road, though there will be a virtual listening party/Q&A on September 18th at 8 p.m. ET, and a release show streaming live on his YouTube page on the 19th at 8 p.m. ET. In the meantime, Anjimile hasn’t stopped writing and already seems eager to follow his grand introduction with the next phase of his musical and spiritual journey.

“It seems like there’s a lot of protest songs in my heart, and a lot of grief, and a lot of chromatic shit is happening for some reason,” he says. “I’m thinking it’s gonna get weird. I’d like to keep expanding the definition of what my sound is.”