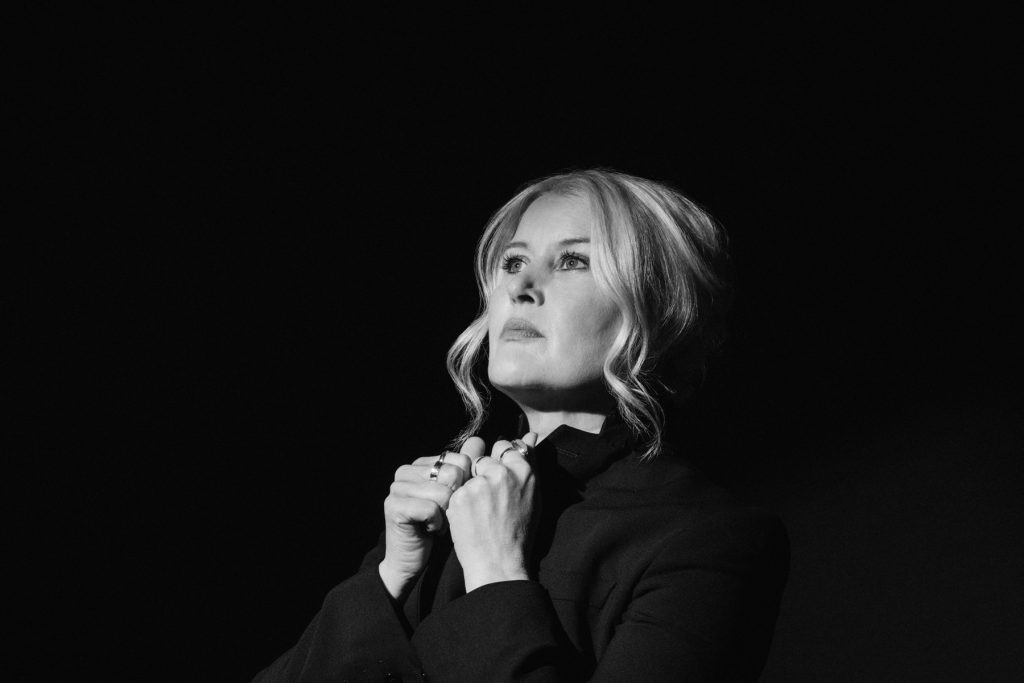

How Allison Russell Broke Free of Her Painful Past

Onboard a stormy flight in July 2019, Allison Russell started thinking back to one of the most turbulent periods in her life. The singer-songwriter fled her abusive home as a teenager growing up in Montreal, spending the rest of her adolescence roaming the city’s streets, sleeping in its graveyards, and playing chess late into the early-morning hours in its cafés. Russell remembered something she used to be told by those who didn’t know what she was going through at the time.

“‘These are the best years of your life,’” Russell jotted down while seated on the plane. “If I’d believed it I’d have died.”

By the end of the flight, Russell had goosebumps: She’d finished writing a song called “4th Day Prayer,” and it was unlike anything she had ever composed in her 15-plus years as a professional songwriter.

“That was when I knew this was a record,” says Russell, 39. “That there’s a whole journey of inquiry that I have to go on here, and it’s going to be painful.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

“4th Day Prayer” was the first song Russell wrote for Outside Child, her stunning debut solo album, which came together over a feverish three-month period during the summer of 2019. Singing a blend of elegant torch songs, ancestral ballads (in French and English), gentle country shuffles, and Al-Green inspired R&B, Russell embarks on a fresh musical beginning by dealing directly with her traumatic upbringing.

“It’s excavating and reckoning with the most painful part of my past, is what it is,” she says. “I just felt that because I can sing about it, I have to.”

Starting at age five, Russell was sexually abused by a close family member. She attempted to work through her trauma as a young singer-songwriter, starting out in her band Po Girl (see the group’s 2010 song “No Shame”). “I was in my twenties and I just didn’t have the support system yet, frankly, to be able to do it safely and honestly,” she says of that time. Russell then spent much of the ensuing decade largely side-stepping the darkest parts of her past as one half of the eclectic roots duo Birds of Chicago, with her husband, JT Nero.

Her latest work is the culmination of a years-long project of searching for the deeper generational, racial, and social roots of the abuse she suffered. “This record is about trying to lay to rest the shame and the anger,” she says, “From 2010, when I was trying to first start talking about things, there’s been much more integration of my own identity and sense of self.”

Russell was inspired to mine such deeply personal material after becoming a member of the banjo-roots supergroup Our Native Daughters in 2018. Before Russell joined the group, she had gone through a nearly four-year period of writer’s block as a new mother. “The only thing I wrote were lullabies,” she says. When the group’s founder, Rhiannon Giddens, first invited her to become a member, Russell was “terrified. I was like, ‘What if I just get there and I have no inspiration, nothing to contribute, and I’m dead weight?’” she recalls feeling. “That was my biggest fear. But what ended up happening was, it was like the dam broke.”

The song that did it was “Quasheba, Quasheba,” an ode to the strength of an ancestor of Russell’s, who, centuries ago, had been captured from her native West Africa and enslaved on a new continent. Writing the song for Our Native Daughters’ 2019 debut album helped Russell understand the ways in which her years of abuse were part of a “continuum of that same white supremacist colonial system.”

“From the coast of Africa/to the hills of Grenada/to the cold of Montreal,” Russell sings on “4th Day Prayer,” tracing her continent-spanning lineage. “That whip, that whip still falls.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-country-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article2″,”btf”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//country//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Despite its heavy inspirations, Outside Child is anything but despairing or academic. Many of its songs mask their dark, difficult tales in deceptively sweet nursery-rhyme melodies (“I’m a violent lullaby,” as Russell herself succinctly puts it, on the gorgeous “Nightflyer”). One of the most jubilant moments on the record comes during “Persephone,” Russell’s ode to her teenage girlfriend and first love, whose home provided a refuge for Russell during her traumatic, transient adolescence.

“You can find joy and happiness even if you have climbed out of horrible circumstances,” says the singer. As if to prove her point, Russell closes the record with an acoustic anthem titled “Joyful Motherfuckers.” “Oh my father, you were the thief of nothing,” she sings in a moment of hard-won clarity, “I’ll be a child in the garden, 10,000 years and counting.”

She recorded the album in three short days in Nashville in September 2019 with producer Dan Knobler (Erin Rae, Rodney Crowell), as well as longtime members of Russell’s extended musical family such as Yola, the McCrary Sisters, and Erin Rae. “So much of my childhood was being isolated and alone and outside that it’s really comforting and compelling to me to feel like I’m in a magic circle,” says Russell. “That’s what a band is to me, a magic circle. It’s a sacred, holy thing, so the notion of stepping out on my own was terrifying.” The process of recording Outside Child, however, still “felt like being inside that magic circle: safer than safe and just endlessly creative.”

Russell’s decision to release her first ever album under her own name at 39 is part of her ongoing project to live up to the legacy of her ancestors like Quasheba. “It’s important for me as a survivor, as a mother, and as someone who wants the abuse to stop with me, to step into my own power and name and story,” she says. “Yes, my childhood was awful. But I have more agency than any of the women in my lineage prior to me. Every person that’s come before — on my Scottish side, too, they all went through unbelievable hardship. If they could survive, then I have to be able to.”