How the U.S. Postal Service Gave Us John Prine

John Prine faced an uncertain future as he prepared to graduate high school in the mid-1960s. Growing up in Maywood, Illinois, Prine quietly considered himself a songwriter, but he’d yet to play his songs for anyone. He was a skilled gymnast, which he thought might lead to college and a career in broadcast journalism, but “my grades were too ugly,” he said. “I could’ve gotten a gymnastics scholarship probably to Pennsylvania or Illinois, ‘cause they had really good gymnastic programs. But my grades just weren’t up there.”

Instead, Prine took the advice of his older brother, Dave, who had taught him how to play guitar, and became a mailman. “I said, ‘Look, they pay good, they got good benefits,” Dave said last year. “And you get a lot of good exercise.”

Prine took a civil service test and was immediately sent to out on a mail route in his hometown, a suburb of Chicago. Mail volume across the country had more than doubled between 1940 and 1960, leading to the introduction of the zip code. “They were really short of mailmen on long, long routes,” Prine said. “They made me a mailman really quick.”

He did not consider himself a great mailman. While other carriers would finish up by 3:30 p.m., Prine was out hours longer on his routes. “I’d be out there so late, it’d be dark,” he said. “And people are having dinner and I’d have to go stand by their dining room window so I could get some light. I’m out in their yard, sorting for the next five houses between my fingers.”

Prine added, “I was on the same route for three years, and a woman comes out of the house one day and asks me when the regular guy is coming back.”

But his mail route had one benefit: It turned out to be a great place to write songs. “I’d just go off into a dream world and stay out there and deliver the mail,” Prine said.

He wrote most of his classic 1971 debut on that mail route. There was “Donald and Lydia,” the waltzing tune about two people who fantasized about each other, and “made love from ten miles away.” There was “Spanish Pipedream,” where Prine suggested the listener “blow up your TV/Throw away your paper.” And there was “Hello in There,” maybe his best song, about the deep loneliness of the elderly. That song came out of Prine reflecting on an even earlier mail route, when he was about 11 years old and helped a friend deliver newspapers. One of Prine’s stops then was a “Baptist old person’s home.” “Some of the folks apparently never got visitors,” Prine said. “They used to act like I was their grandson or nephew or something. They’d have a visitor in the room and they’d act like I was somebody that they knew, and I’d just play along with them. That’s the first inkling I got of how lonely they were.”

The USPS route provided the time and space for Prine to reflect on the unordinary characters and emotions that came to define his music. “Those early songs, a lot of the stuff I was writing about were things I saw and felt and didn’t hear them in songs,” he said. “I certainly didn’t hear them in songs or the stories that I read, the novels. It was about certain silent things that people didn’t talk about. And when they were talked about, it was probably in an argument, or dismissed. And that’s basically what I was writing about those early songs. Whether I was writing about an individual, like ‘Quiet Man,’ – it was all stuff about communication, or non-communication.”

“You’d meet some interesting characters,” Prine said. “I remember a diner I used to eat in. It was a little truck stop. And there was a ventriloquist. The waitress would keep her dummy up on top of the milk machine. And if any of the truckers would, you know, get smart with her or anything, she’d have the dummy call ’em out. She’d talk back and forth with the dummy: ‘He has no right to call you “babe.”’ And then the other guys would end up laughing the guy out of the place. Really colorful, rich stuff.”

Prine also used his time delivering mail to reflect on the politics of the late Sixties. His mail route included delivering a lot of issues of Reader’s Digest. One of those issues included an American flag decal as the Vietnam War was heating up. “They didn’t say why, they just put a free flag decal in with every issue, and I had to deliver them,” Prine said. The following day, he noticed, “‘Everyone had stuck ’em either on their car or on their front door. It was the silent majority. It was their way of saying, ‘Don’t mess with my America,’ you know?” Prine wrote “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You into Heaven Anymore.” “I thought that song would last about six months,” Prine said. “I mean, people are always out there waving the flag for the wrong reasons. And that song just won’t die. We get just as much attention for that song as we did 45 years ago.”

Prine had to take a break from his life as a mailman when he himself was drafted to serve in the war. He lucked out when he was sent to a base in Germany, but a lot of his friends weren’t as lucky. “I knew a lot of guys that went there,” he remembered. “And a lot of the ones that came home never really came home. These were friends of mine I’d grown up with. It was really odd. None of them had stories that they were in a lot of combat or all that – it was just living under the [threat] of what might happen. One friend told me you could be going to get a beer at night and a buddy of yours would step on a land mine. And it was going on around you.” Prine wrote “Sam Stone” about the mental toll of the war on veterans, with his classic line “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes/Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose.”

He worked up the courage to play “Sam Stone” for his brother Dave. “It was just like wow, where did this come from?” said Dave. “Because he’d shown absolutely no singer-songwriter tendencies at all before that. This was clear out of the blue. And evidently he had a bunch of stuff he had done. One of his stories was, on the mail route, they had a central collection box you put your stuff in. And he would get in there and shut the door and work on songs. And it just blew my mind.”

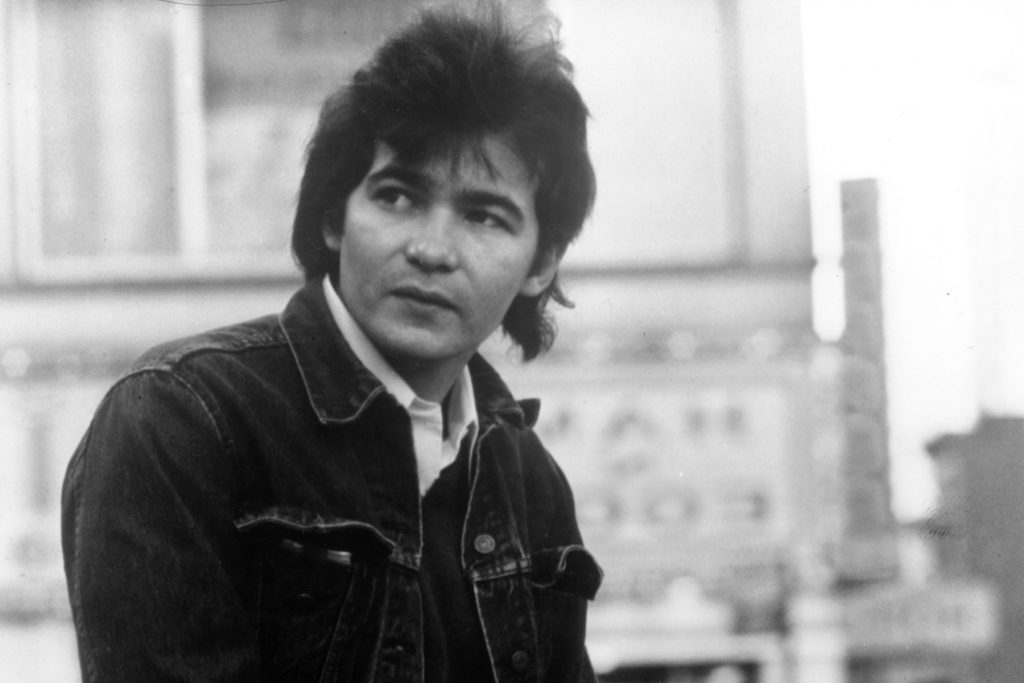

Prine soon got onstage at an open-mic night to test out the songs he’d written while delivering the mail. He was offered a job on the spot. That year, Roger Ebert, who was working as a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, walked in and saw Prine for the first time. Ebert wrote a column that ran with the headline “Singing Mailman Who Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words.” “I didn’t have an empty seat after that,” Prine said. “Cause of Roger Ebert.”

Donald Trump has made it clear that he’s not a fan of the U.S. Postal Service. He’s called it “a joke,” blocking emergency funding for the service during the Covid-19 pandemic — and in May he installed Louis DeJoy, a wealthy Trump campaign donor, as the new postmaster general. DeJoy has put an end to overtime for postal workers, ordered the removal of sorting machines from post offices, and shuffled the USPS leadership, leading to mail delays and widespread outcry. In his eulogy for civil rights hero John Lewis, former president Barack Obama said Trump was attacking voting rights “with surgical precision, even undermining the Postal Service in the run-up to an election that is going to be dependent on mailed-in ballots so people don’t get sick.”

Prine isn’t here to weigh in on the subject; he died of Covid-19 complications in April. But he often discussed the way that working as a postal carrier gave him the freedom and security to hone his craft as a songwriter. He was just one of countless hard-working Americans who have found a steady job with the USPS, serving a crucial function in our democracy and building a life of dignity for themselves. “I knew until I decided what I wanted to be, it was a good place to be,” Prine said. “Because I didn’t have to worry about any bills or anything. The post office didn’t drive me crazy. I could handle it.”

At the first night of this year’s Democratic National Convention, the mail was a major subject of discussion. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada denounced Trump’s efforts to defund the USPS: “Seniors won’t be able to get their prescriptions because he wants to win an election. Mr. President, America is not intimidated by you.” There were stories from people who have lost family members to Covid-19. “Enough is enough,” said Kristin Urquiza, whose father died of the virus this summer. “Donald Trump may not have caused the coronavirus, but his dishonesty and his irresponsible actions made it so much worse.”

Prine’s music made an appearance at the convention, too: “I Remember Everything,” the single that his family released after his death this spring, soundtracked a moving tribute to the lives lost to the pandemic.

In a conversation in Ireland two years ago, Prine talked about the Trump presidency. “I gotta say, this reminds me of when Nixon was president and we were in Vietnam,” he said. “Nixon’s politics and Trump’s politics are two different things. But along with us being so involved in Vietnam that there wasn’t a way to get out, and [Nixon] being President — those were really tough times. I think the country is almost just as divided now as they were then. I’m 71 years old, I would expect that within my lifetime the country has learned some lessons. It doesn’t seem so. It’s gonna take somebody really special to bring the country back together. I don’t know who that’ll be. It won’t be me.”

pic.twitter.com/WbI8zpWbtC

— John Prine (@JohnPrineMusic) August 18, 2020