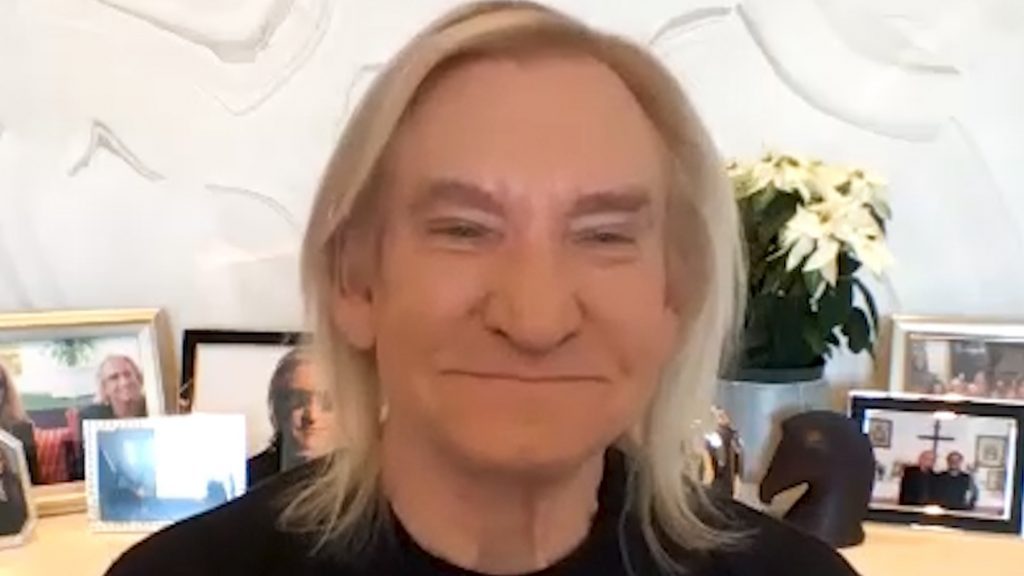

No I.D. Still Believes We Can Fix the Music Industry

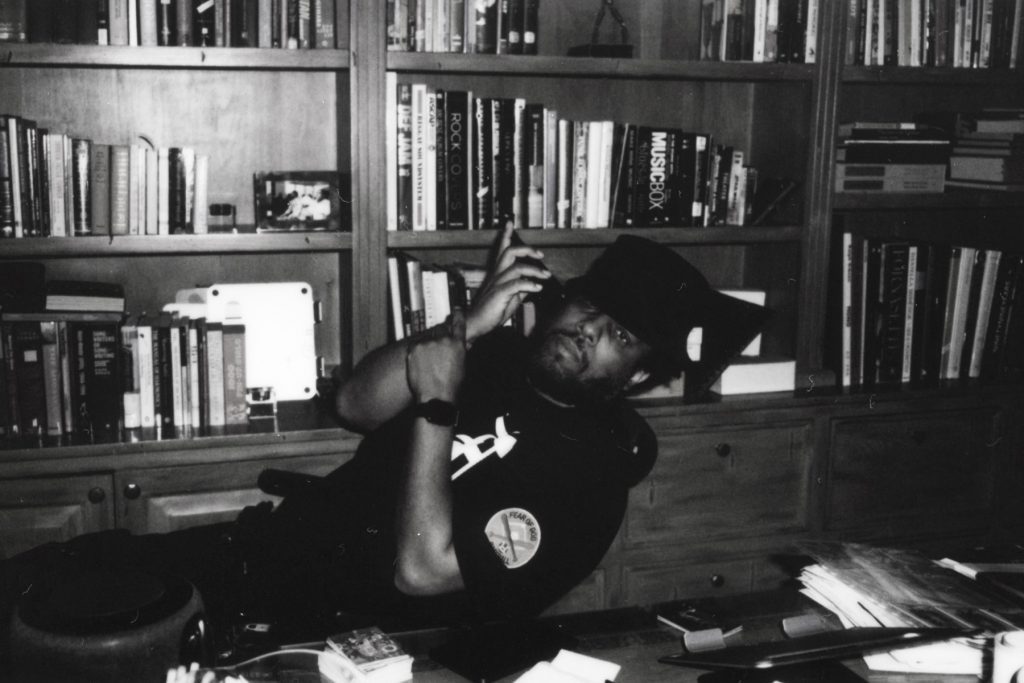

This summer, five A&R veterans convened on Zoom to discuss racism in the music industry. As protests erupted around the country after the killing of George Floyd, various music companies made statements supporting equality and announced donations to organizations fighting for racial justice. This virtual panel was notably different — instead of offering feel-good bromides about inclusivity, the participants discussed the ways that the music industry is complicit in systemic racism.

The five men took turns speaking bluntly about the bias they faced while working at labels, even as highly successful executives. One of the speakers, the producer and A&R No I.D., pointed out that “pop” was a troubling term that harmed black acts and openly wondered why his generation put so much stock in holding down jobs at companies that often seem to care little for the wellbeing of black artists and executives.

This felt shocking in the context of a music industry where most people invariably toe the party line. But these remarks weren’t out of character for No I.D., a soft-spoken leader intent on remodeling and rehabilitating the modern music industry even while he walks its corridors of power.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

No I.D.’s peers compare him to both “the Black Godfather” — Clarence Avant, one of the most powerful behind-the-scenes players in music history, who managed Bill Withers and helped Janet Jackson become a perennial hit-maker — and Yoda from Star Wars.

“One thing him and I always joke about, we say, ‘they hate to educate a Negro,’” says Eddie Blackmon, vp of A&R at AWAL and organizer of the Zoom panel. “A lot of times we’re just happy to be in the building, but we’re not understanding how the game is actually played. [No I.D.] is that person who helps educate us, black executives.”

In a year when the dirty laundry of the music business got hung out in plain view, No I.D. is adamant that “we can correct the system” — or at least construct a better one. “We don’t have to change anyone’s [existing] company,” he adds. “We need to build different companies that have different models and different perspectives.”

In April, he took his label Artium independent, giving him a chance to test this theory firsthand. If Artium is viewed as a triumph, it could have ripple effects throughout the music business, showing other executives, especially non-white ones, that it’s possible to impact the industry’s architecture without dynamiting its rotten foundation.

No I.D. was never interested in an executive job. But even as a kid, he held sway over those around him. “He always had a lot of influence,” says Common, who has been close with No I.D. since they attended fourth grade together. “My friends used to joke, instead of saying ‘C.R.E.A.M.,’ cash rules everything around me, they would say ‘D.R.E.A.M.,’ for Dion rules everything around me. Everything he said, cats was listening.”

No I.D. also didn’t need an executive job, considering how successful he was as a producer. His early friendship with Common turned into a fruitful creative partnership — No I.D. was responsible for the majority of the beats on the rapper’s first three albums, establishing himself as a beat-maker with an ear for a golden sample and an ankle-breaking drum pattern. Songs like “I Used to Love H.E.R.” and “Stolen Moments – Part III” remain shining specimens of Nineties boom bap.

Common’s music with No I.D. didn’t storm the charts, but after a lull in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the producer started to rack up a slew of hits, first working with Jermaine Dupri — Bow Wow’s “Let Me Hold You” and “Outta My System” — and then Kanye West, whom No. I.D. briefly managed a few years before he became a superstar. West and No I.D. collaborated on West’s own “Heartless,” Jay-Z’s “Run This Town,” and Drake’s “Find Your Love.” Working on “Heartless” and “Find Your Love” helped push auto-tune into hip-hop’s mainstream, showing that No I.D. wasn’t constrained by his spotless traditionalist resume.

He could have kept bouncing from one star-packed session to the next until retirement, but in 2009, West demanded that No I.D. take the reins of his G.O.O.D. Music label. “One day Kanye goes, ‘G.O.O.D. Music is over — if you don’t become the president, I’m distancing myself from this,’” No I.D. said in 2018.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

;

});

“I really felt like, as a creative, I have a hard time speaking with people who don’t understand what I’m talking about when it comes to music,” No I.D. says now. “I thought I might as well bite the bullet and make myself available to help others by sitting in those types of positions.”

As No I.D. moved from running G.O.O.D. Music to helming the A&R department at Def Jam and then to a position as EVP of Capitol Music Group, he confused many of his new colleagues. Because of his background in production, “when most people saw me being an exec, they were just like, ‘go in the studio,’” he recalls. Instead he went out of his way to spend hour after hour in tedious label meetings.

“I was the guy who went to every single person’s office,” he says. “What do you do? How do you do it?”

No I.D. hoped to learn how to tackle a long-standing issue in the music industry, one that had plagued him as a young producer eager to make an impact. Labels are ground zero in a never-ending cold war between musicians and executives, where art first collides with the cruel commercial machine. “Creatives make music, think it’s good, want someone to promote it,” No I.D. explains. “That’s how simple it is to us. Creatives don’t have to be politicians. They just make demands and threats.”

The problem, according to No I.D., is that labels are constructed to be impervious to demands and threats. “Systems are set up to deal with that already,” he continues. “It’s already pre-assumed that people who are not familiar with the way things work will come in with the same complaints, and there is already a script set up for that.” This leaves artists and executives talking past each other, each lacking the experience, and thus the language, to communicate with the other side.

With no one to mediate, interactions can become increasingly opaque and frustrating. A label, for example, may refuse to approve an artist’s marketing budget until the artist picks a release date for an album. “Transparency is more your friend in these situations,” No I.D. says. But because “most companies are so vilified, the artist wants to not communicate with the company as much as possible,” making the situation even worse. “If you don’t pick a date because you’re trying to be secretive,” No I.D. explains, “you’re actually working against yourself within the system.”

No I.D. began to take on the role of translator, a bridge between the artists and the bean-counters. “He’ll put things in perspective where people can learn and not feel like they’re being manipulated,” says Noah Preston, senior vice president of A&R for Def Jam, who has worked closely with No I.D. on albums for both Jhené Aiko and Logic. “A lot of people at his level don’t give everyone the patience and the time. But Dion can come in like, ‘you probably shouldn’t have signed this if you feel this way. I did a horrible deal back when me and Common did this album.’”

I.P.W. (2)*

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

At the same time, No I.D. can advocate on the artist’s behalf in a way that makes sense to the men — and it’s almost entirely men — who control the labels’ purse strings. “He’ll go back to the label and be like, ‘so-and-so feels disenfranchised,’” Preston adds. More importantly, he’ll say, “you guys should probably fix this.”

Executives are often ranked according to the number of artists they have helped “break” — acts ushered from unknown to commercially successful. In his time as an executive, No I.D. has been instrumental in the rise of Aiko (more than two billion streams in 2020 alone, plus an Album of the Year nomination at the upcoming Grammys), Logic (more than one billion streams in 2020 so far), Big Sean (more than 800 million), Alessia Cara (more than 400 million), Queen Naija (more than 400 million), Snoh Aalegra (more than 200 million), and Vince Staples (more than 100 million).

But No I.D. is equally interested in nurturing like-minded executives — a valuable break for anyone, but an especially rare opportunity for black men and women in the music industry, who are underrepresented in positions of power relative to their white counterparts. “I’m not sure he thinks he’s a mentor, but that’s what he is to a lot of people,” says Daouda Leonard, a manager and the CEO of CreateSafe. “He’s always providing sage advice in public and private forums.”

“It’s ridiculous how many people are affected by the expert tutelage of Dion,” adds Blackmon, who got his first industry job at G.O.O.D. Music.

In 2019, Blackmon got a dollop of No I.D.’s wisdom when signing Aalegra to AWAL. The Swedish soul singer was hotly pursued at the time, and in the streaming era, headlines about multi-million dollar record deals have become routine. But “Dion said, ‘let’s not do that [type of flashy deal],’” Blackmon recalls.

Instead, the two men agreed on a reasonably affordable deal where Aalegra received additional injections of funds each time she hit pre-set streaming benchmarks. This ended up being a win for the singer, who quickly recouped her advance and soared past the benchmarks, for Blackmon, who brought in a “very economical” deal, and for AWAL, which is still making handsome profits from the relationship, even though it only lasted for one album.

No I.D. says that in situations like this, he is just trying to replicate a dynamic that helped his own career. “It’s important that I let people know that I sought mentorship,” he says. “I sought counsel with older producers. Jay Brown [co-founder of Roc Nation] helped me learn how to negotiate.” (“I just told him that ‘no’ is a very powerful word,” Brown says.)

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Still, many of those who have benefitted from No I.D.’s generosity with advice and business acumen — “We were calling him Yoda when we was in our early 20s,” Common jokes. “Where Yoda at?” — say it sets him apart in a hyper-competitive music industry. Sam Taylor, executive vice president of A&R at Republic Records, explains that the way No I.D. conducts himself “is probably the complete opposite of what most people do” in the music business.

“It’s very easy for a lot of us in the game to say, ‘I’m gonna look out for this person,’” Taylor adds. “But he actually does it.”

Fitting for a man who chose a moniker about lacking an identity, No I.D. doesn’t do a lot of interviews; several times in the course of a 90-minute conversation, he says he’s uncomfortable with doing this one as well. “That’s why he got the name No I.D. — it’s Dion backwards, but he liked playing in the background,” Common explains.

But No I.D. took Artium independent in April, leaving behind a position as EVP of creative at Universal Music Group, and perhaps it’s not a coincidence that he has been somewhat more outspoken than usual in the subsequent months. He has popped up in discussions on the social media app Clubhouse, which is popular in the music industry, and appeared on Blackmon’s lively panel.

At the time, some segments of the music industry were debating whether they should continue to use the term “urban” as a blanket description for music made by black acts. No I.D. was quick to point out that this debate was essentially irrelevant, the equivalent of treating a symptom without addressing the underlying disease: “Whether we got the word or not, there is still a system in place that prejudges what we do,” he said.

“Let’s talk about getting rid of the word ‘pop’ too, cause I don’t know what that is,” No I.D. continued. “You go to your department and you say, ‘I got a record and it’s pop.’ Well, [the way the major labels work,] black people don’t go straight to pop. Black people gotta go through urban and rhythmic first… [labels] don’t just let [black artists] into the biggest market.”

Due to this sort of bias, No I.D. admitted that he frequently felt “uncomfortable” working as an executive. And while his tone was calm, his frustration with the music industry was evident. “We’re putting our foot in a snake pit acting like it’s rabbits in there,” he said. “We get our foot chewed off. We gotta go sit down and heal up. Then the next person puts their foot in and it’s a cycle.”

Hunting for the right analogy, No I.D. compared the challenge of label reform to activists’ ongoing efforts to improve problematic police departments. “Do we need to go into the police department to make the police better, or do we need to defund the police?” he asked. “I’m not saying I have the answer. But it’s the same question.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

At one point during the panel, Blackmon posed another question. “Do we have a real shot of being in the rooms, having a seat at the table, being able to dictate change [in the music industry]?” he asked. “Or is it all a mirage?”

Sha Money XL, another participant on the Zoom call, didn’t hesitate. “It’s a mirage,” he replied.

While the panelists were united in doubting the music industry’s capacity for positive change, No I.D. disagrees with some of the harshest critiques of the business that flourished in the wake of Blackout Tuesday. “I know the difference between systemic racism and capitalism,” he says. “A lot of the people that are being attacked are mainly capitalists. They just want to make as much money as possible by any means. Is that a crime? I don’t think so.”

And he’s as likely to critique would-be music industry rebels as the industry. Record labels have historically taken ownership of artists’ master recordings in exchange for bankrolling their careers; today it’s increasingly common for artists to talk about the importance of retaining those masters. But “not many people know what to do with them if they own them,” No I.D. says. “You gonna put ’em in a suitcase?” he jokes. “Lock ’em in a safe?”

“What’s the reason to not sell your masters, that’s something I’ve heard him talk about,” Leonard adds. “Do you actually know how to exploit that master to its fullest? Record labels do, or at least they’re supposed to.” No I.D. sold off the rights to his own catalog, encompassing more than 270 songs, this summer.

“Ultimately I’m not here to oppose a company that makes superstars,” No I.D. says. “I want to work with companies that do that. But how we work together, what the terms are, that’s where the real conversation should be.”

Artium is a chance for No I.D. to lead through example, to build a successful label by emphasizing education instead of exploitation, collaboration instead of competition.

No I.D. started Artium at the same time he joined Def Jam; his initial deal allowed him to sign one act to his own label for every act he signed to the bigger company. No I.D. wasn’t able to focus on Artium much while working at Capitol, but now that he is out on his own, he’s grown the label to six acts.

Aalegra is currently Artium’s biggest artist — a success, if not yet a superstar — and the strongest demonstration that No I.D.’s approach can pay off outside of the major-label system. “Most execs care about you when you’re hot and don’t give a damn about you when you’re not,” Aalegra says. Her career, on the other hand, has been a testament to the power of the slow burn. She had a few false starts in the industry, which tried to push her away from the R&B she loved. Working with Artium, she has demonstrated a knack for neo-soul songs that are emotionally bracing but musically serene, and her commercial growth has been steady. She was named Best New Artist at the Soul Train Awards last week.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Aalegra is joined by acts like Jordan Ward, who is starting to build a following with airy, yearning tracks like “Sandiego,” and Sonny, who No I.D. estimates has already written more than 500 songs this year. These artists will surely benefit from the fact that No I.D. is comfortable taking views that many executives find counterintuitive. Label higher-ups are often known for their egos — they ultimately have a degree of control over which artists are prioritized and how, and they want you to know it.

But No I.D.’s philosophy is different. “That’s another skill I’ve had over time, not making myself a gatekeeper for talent,” he says. “It’s not, ‘this is what you need to do, and this is how it needs to go.’ It’s: ‘What do you want to accomplish, and how can I help?’”