Suzi Quatro on Landing the 1975 Cover of ‘IndieLand’

Suzi Quatro’s life and career as a female rock pioneer is chronicled in the upcoming documentary Suzi Q, which arrives on-demand on Friday. On Wednesday, the documentary will premiere virtually, featuring a Q&A with Quatro, the Runaways’ Cherie Currie, and the Go-Go’s Kathy Valentine.

“The reaction to the documentary is so terrific,” Quatro tells IndieLand on the phone from her home in Essex, England, where she’s lived since 1980. “People are loving it, that it’s warts and all, and exposed and vulnerable. It tells you the story of how the first person who did it — which was me, that’s in the history books — it tells you that story, and it tells you well.”

Hopefully the documentary will rectify Quatro’s forgotten status in the U.S., where she’s mostly remembered for portraying Pinky Tuscadero’s younger sister, Leather, on Happy Days. Still, she had a major moment in America, specifically when she appeared on the January 2nd, 1975, cover of IndieLand.

Right between a December 19th, 1974, cover of George Harrison and a January 16th, 1975, cover of Gregg Allman was Quatro’s cover story, written by Anthony Haden-Guest and aptly titled “Suzi Quatro Flexes Her Leather.” For the photo, Quatro appears in — yes — all leather.

Ahead of the documentary release, Quatro looked back on the cover, her career, and her legacy.

What’s it like being off the road?

Very strange. I’m lucky in a way that I had one of the best years of my entire career last year. Which has made this maybe a little bit easier to bear. I did, like, 80 shows. I put out an album that just went ballistic everywhere [No Control]. The critics raved. I put out my documentary, which is now coming out in America. I just had such a high year, you know? I even thought to myself, “Well, if everything finishes tomorrow, I can hold my head up.”

It’s crazy. After 56 years of doing nothing but gigs, to not be doing them. But saying that, I have the mindset that I have to keep busy. It’s how I am. So I have been extremely creative. Even social media, I’ve been doing my bass-line tutorials every day, and that’s a lot of work. You’re talking maybe, I don’t know, maybe three hours to put down one track because it’s sometimes stuff you haven’t played since 1973. And I’ve been doing my Sunday Specials. This is all being filmed, and I do songs stripped back at the piano. I’ve written 14 songs for the next album. My last album was with my son, written and produced, and everybody loved it. So we’re doing another one.

I’ve assimilated a lyric book from scratch while I’ve been on lockdown, called Through My Words. And I’m working on the script of my movie, which is hot on the heels of the documentary because of the attention it’s gotten. They signed me to do a movie, so that script is being worked on and July 17th is the delivery date.

How does it feel that the documentary is finally coming to America?

Well, it should have been there in March. I was booked to come to Frisco to do the first opening at the Sonoma Film Festival. And, of course, that got canceled. I’m not the only one this has happened to. It’s happened to everybody. But now it’s finally coming there, a little bit delayed. You’re the last people to get it, because it just worked out that way. You know, you were late in coming to the table, anyway. It’s the last one that was going to show it. So it doesn’t matter. It’s coming there now. People are going nuts over it. There have been rave reviews.

What’s good about it coming to America is that you’re often only remembered for your role on Happy Days.

I know! It’s so crazy. Do you know that that’s the only country in the entire planet where people talk about me that way? Everywhere else in the world, even where the show has been popular, they say, “Didn’t you do Happy Days?” It’s like the opposite way around. But it doesn’t matter.

I didn’t have the catalog of hit singles in America that I had everywhere else. I had album success, tour success. Everybody definitely knew me, but the singles weren’t as big there. So this is how they came to my table, through Happy Days. And that’s OK, as long as you’re there now. As long as you’re at the table, then we’re on the same page.

Tell me about appearing on the cover of IndieLand.

I’ll never forget it. As you know, I’m American. I’m from Detroit. I was born and raised there; I didn’t leave there until I was 21. So IndieLand was like the Bible. It was quite a thrill to be on the cover. I have it upstairs framed in my Ego Room. Everybody has these moments in their life. I look at that picture and I say to people, “I looked good that day.” I’m really proud of that picture. It’s a good one, isn’t it?

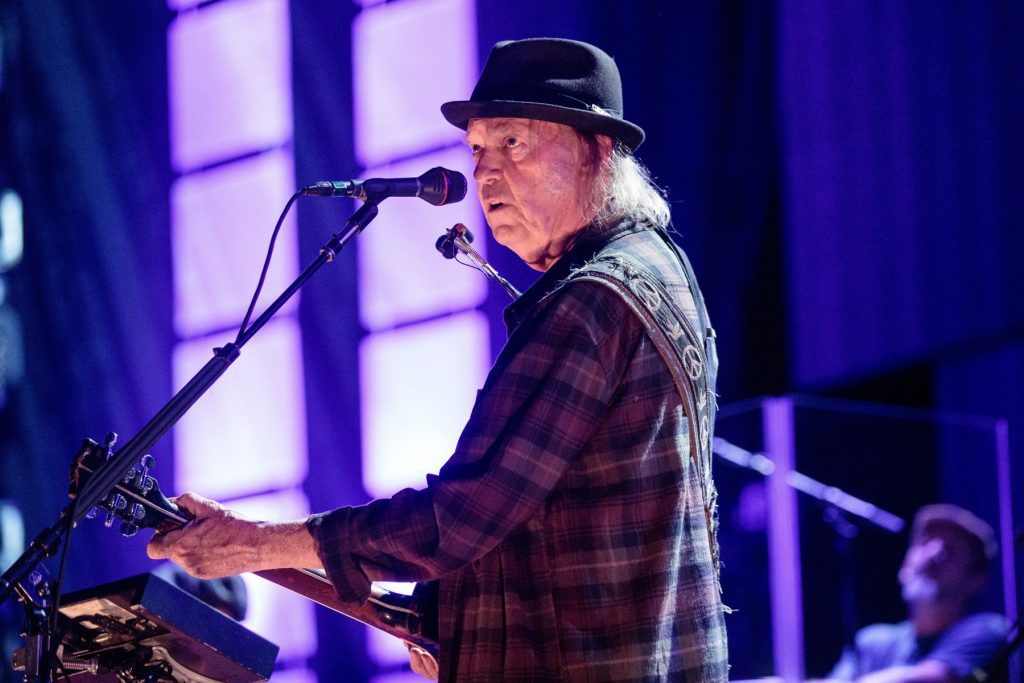

Suzi Quatro on the cover of the January 2nd, 1975, issue of ‘IndieLand’

Photograph by Peter Gowland

Were you familiar with the writer?

I knew the writer. He had done a big piece on me in England, and it was our second interview together. They asked him to do it. It was all good. It’s a proud moment to be on the cover of IndieLand. Who had it? Dr. Hook [and the Medicine Show]. I didn’t need the song. It’s still a good magazine. I still buy it now.

There’s one part that comes off as a bit sexist to me. Can I read it to you?

Sure.

“Nor is the significance of being a titchy lady gripping that monster instrument between her thighs entirely lost on her. ‘Yeah, it’s phallic.’ The drums move the arse, she says, the guitar is for the head, but the bass ‘gets you right between the legs.’ It is, she observes, horny. And the hornier she gets, the more she wants to play her arse off.”

I don’t know where they got that from. I was quoted as saying — which I said years ago, and I remember saying it — that every instrument touches a different part of your body and the bass hits you right where it should [laughs]. Maybe that’s where he got that from.

Who knows when these men write these stories. You’ve got to forgive them, their little forays into fantasy. I never played the sex card. I never played the female card. So if this guy played it, he played it on his own. It’s like masturbation. Who cares? That’s not who I am. You always will get this from some guys, but I really don’t even pay any attention to it because I have such self-awareness.

So all these years later, what do you think you achieved for women?

You’ve seen the documentary. It says it all in there. All these women, one after the other, from young to old, coming up and telling me that I opened the door. I can’t say I did it on purpose — I was just sticking to who I was. I won’t compromise. That’s the way I am. There was not even a guarantee I was gonna make it. I could have failed miserably because what I was doing was not done before. I didn’t have a blueprint. I feel great now, in hindsight, that I was able to give women permission to be who and what they wanted to be. That’s what I take to my grave. I gave them permission.

This movie has really made me stop and re-evaluate. When I see these women coming up … Cherie Currie is giving me an award at She Rocks, and she’s in tears. I’m doing an interview with Kathy and Cherie on Zoom, and Kathy starts crying. This happens to me all the time. And this is why I have re-evaluated what I’ve done.

It’s more than just opening the door. It’s more than that. It’s giving women permission to be. There are so many women who don’t belong anywhere. That’s what I had. Where do I belong? I don’t know. I found my voice, and once I found my voice, I wasn’t going to shut up for anybody. And because I found my voice, I gave permission for women who are unusual or don’t fit here or don’t fit there. They looked at me and said, “Oh, my God, if she can do that, I can do this.” That is a wonderful legacy to leave.

What are your views on feminism now?

I’ve never been a feminist as such because I don’t actually do gender. I never have. I’ve never, ever called myself a female musician. Doesn’t occur to me. I’ve been more of a me-ist. This is what I preach: I preach to be who you are. Male or female, rich or poor, black or white, whatever your religion. Nothing matters but being and becoming everything that you have the ability to be. There should be no limitations. That’s how I see life. And I’ve always seen it that way.

It didn’t occur to me even when I was starting out; when I first saw Elvis at the age of five going on six on TV, I had that light-bulb moment — I really did, this is no bullshit — and I thought, “I’m going to be like that. That’s who I’m going to be.” It didn’t occur to me for a millisecond that he was a guy and I was a girl.

And when somebody said to me, “You’re gonna play the bass,” I just said, “OK.” That’s just the way I’m wired. So I think in hindsight now, and this is at the age of 70, that the reason it fell onto my shoulders to break that door down was — because I don’t do gender. I don’t think it would have worked with a woman up there who was maybe big busted and maybe a little bit like, “Here I am, a girl! I can do it, too!” That kind of attitude. It’s just the way it was supposed to be.