The Year Fandom Went Underground

Twenty years ago, in The Village Voice’s yearly poll of music critics, one of the writers quipped about the future: “So who’s going to be paying $300 a seat for the Backstreet Boys reunion at AOL Hard Rock Cafe in 2020?” As it happens, $300 would have snagged you a general-admission pit ticket for the Backstreet Boys’ summer tour at the Jiffy Lube Live venue in Bristow, Virginia, on July 21st. Except this show didn’t happen, and neither did the rest of their DNA Tour. Nor did anybody’s tour.

Instead, the Backstreet Boys got stranded like the rest of us. All five of them combined for one of the year’s most strangely touching music moments: Elton John’s live-TV Covid-19 benefit in April, when the BSBs Zoom-harmonized “I Want It That Way” from their separate homes. No “reunion” necessary — they just made a Number One album last year. (They had to cancel a tour in 2009 when Brian got swine flu — until now, that was a big-deal pandemic.) They looked awkward, unsure how much swagger fit the moment, or whether they felt ridiculous posing as pop idols in front of their goofy couches. And it was ridiculous — that was the beauty of it.

This may not be the way we wanted it, back in the “I Want It That Way” day. But as Mick Jagger sang when it was the IndieLands’ turn to do the Zoom live-TV honors, you can’t always get what you want.

This was the year fandom went underground. In 2020, being a music fan meant listening by yourself, more than ever, as the coronavirus ravaged the country and our lives. Being a fan in 2020 was crazy in ways that were totally new, because everything about pop life changed overnight. We didn’t get to hear “WAP” in the club or at a party. We didn’t rock out to our favorite new songs live. We didn’t get that shared public experience of music. Isolation became a major fact of life, and the music reflected that. For so many of us, music is key to how we connect to the outside world. But in 2020, music became the outside world, as public spaces were few and far between. It was a shared experience at a time when we really needed that.

Pop music got lustier and hornier all year as a direct response. Ariana Grande made a fantastic album called Positions, basically a grinding-at-the-club thirst trap. It really encapsulated the year in pop fandom — a sex-crazed fantasy lovingly crafted by, for, and about people who aren’t doing any of the wild and crazy things in the songs. Remember the Ariana who sang “Break Up With Your Boyfriend, I’m Bored”? So does she, and there was something heroic about keeping that spirit alive this year.

Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion dropped everyone’s favorite summer sex jam, “WAP,” announcing the presence of whores in the house. When “WAP” hit Number One, it replaced Harry Styles’ “Watermelon Sugar” — I love that: two songs about the same thing, as different musically as two songs could be, yet kindred spirits as two of the year’s filthiest hits in the least Hot Girl Summer of all time. Part of why “Watermelon Sugar” felt timely was the video Harry filmed on the beach in January, right before lockdown, with the intro: “This video is dedicated to touching.”

Two of my favorite albums this year, by Dua Lipa and Jessie Ware, were shut-in disco fantasies self-consciously designed to evoke the neon glittered-up dance-floor sweat that fans could only imagine from afar. There was something beautiful about that, like the glitzy Busby Berkeley musicals in the Great Depression — not really escapism, just a shared communal desire.

Everything about being a music fan was so different in 2020. You wouldn’t expect a Buckcherry show to be a place where people take their lives in their hands to hear “Crazy Bitch” at a superspreader festival. Hell, “Super Spreader” sounds like it should be the name of a Buckcherry song, right? But the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota in August was basically a feed-the-virus benefit concert, designed to protest the idea that there was any kind of public-health emergency, starring a bunch of bands you might have hoped would do better: Smash Mouth (yep, what a concept), Lit, 38 Special, Quiet Riot, Night Ranger. It sounds ridiculous to catch yourself saying “I’m disappointed in Buckcherry’s moral choices,” but it was that kind of year (and I ride hard for Buckcherry’s anti-Iraq War-protest period). Smash Mouth, whose most famous concert previously was the 2015 Colorado gig where the singer yelled at the crowd to stop throwing bread slices at him, declared, “Now we’re all here together tonight, and we’re being human once again. Fuck that Covid shit!”

Sadly, by the fall, South Dakota was utterly ravaged by viral infections, leading the nation in cases and deaths per capita. By November, South Dakota had more Covid fatalities than South Korea. Your brain gets smart, but your head gets dumb.

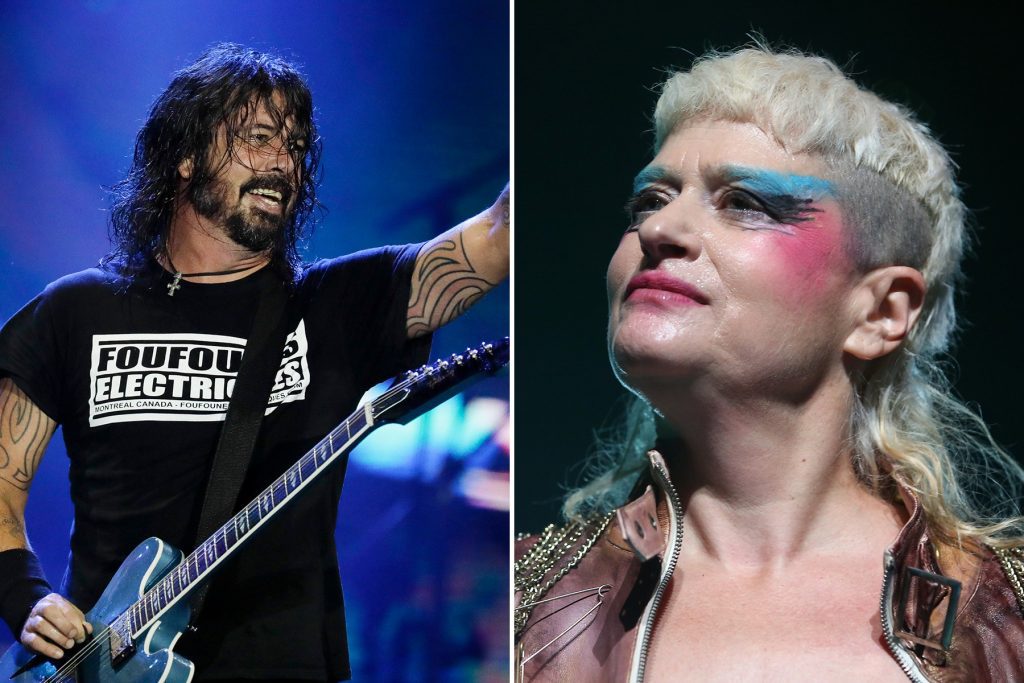

I kept getting reminders about all the 2020 shows I grabbed tickets for that never happened: Ticketmaster sent me the worst email subject line of all time: “Stephen Malkmus Has Been Canceled.” Dave Grohl, a mensch as always, spent the year in a video drum battle with a 10-year-old girl across the country — and, as he proudly admitted — losing. Miley Cyrus sang Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” on SNL — so right for her voice, so right for the moment. Paul McCartney called it “rockdown,” a very Paul way to put it, but he spent his downtime on the farm making a spontaneous album that wouldn’t have happened otherwise, just like Taylor Swift did. Artists dropped home recordings that otherwise would have sat on hard drives.

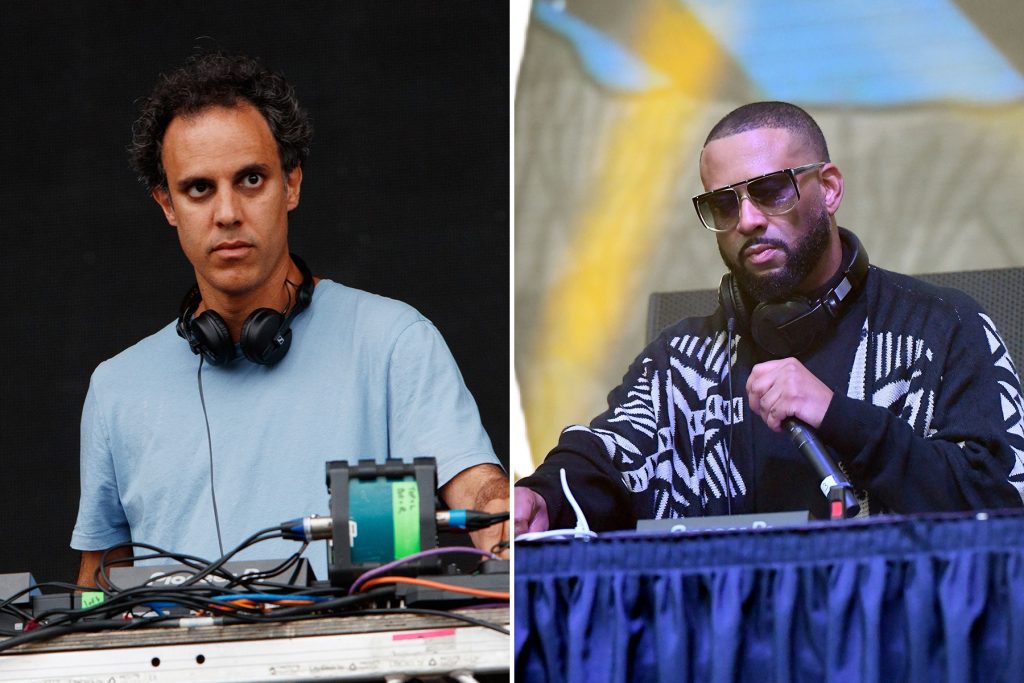

The audience had to fill the void, looking for other long-distance ways to share that ritualistic fan experience, from Verzuz battles to Bandcamp Fridays. Tim Burgess, the U.K. rock star from Manchester’s the Charlatans, did his Twitter listening parties, which became a surprisingly therapeutic way for music fans to listen together worldwide, with the artists themselves live-tweeting along. Rock stars who seemed long lost, or reclusive, or just plain forgotten, came out of the woodwork — like the members of New Order, who haven’t spoken in years, bitching out one another on Twitter. They all knew this was the biggest audience they’d get all year.

Music was part of the year’s cultural upheavals, from the summer’s Black Lives Matter uprising to the November victory celebrations when Joe Biden and Kamala Harris beat Trump, with dancing in the streets. Within an hour of Pennsylvania getting called, I was in a Brooklyn park in the Saturday-afternoon sunshine, caught up in the middle of a spontaneous dance party (everyone masked up and nobody uptight about it). There was a psychedelic jam trio playing, the first live band I’d gotten to hear in eight months. The DJ was blasting “Y.M.C.A.,” the gayest of Seventies disco anthems, as well as the song Trump bizarrely claimed as his personal campaign-rally theme. Every banger the DJ busted out felt perfect: “Thank U, Next,” “Bodak Yellow,” “Get Ur Freak On,” “Beautiful Day,” Chic’s “Good Times,” YG’s “FDT,” and of course, Stevie Nicks’ “Edge of Seventeen.” It all felt cathartic, tinged with a lot of dread and a little hope. In other words, the combination that pop dreams are always made of — and a moment to carry over into 2021.

if(typeof(jQuery)==”function”){(function($){$.fn.fitVids=function(){}})(jQuery)};

jwplayer(‘jwplayer_c132tQIF_zFOPDjEV_div’).setup(

{“floating”:true,”playlist”:”https:////content.jwplatform.com//feeds//c132tQIF.json”,”ph”:2}

);