‘The body was the drums, the brain was the synthesiser’: darkwave, the gothic genre lighting up pop

For whatever reason, there is a huge appetite right now for music that embraces a moody, minimalist, synth-heavy, often lo-fi sound that feels redolent of an amphetamine-charged squat party in 1980s West Berlin.

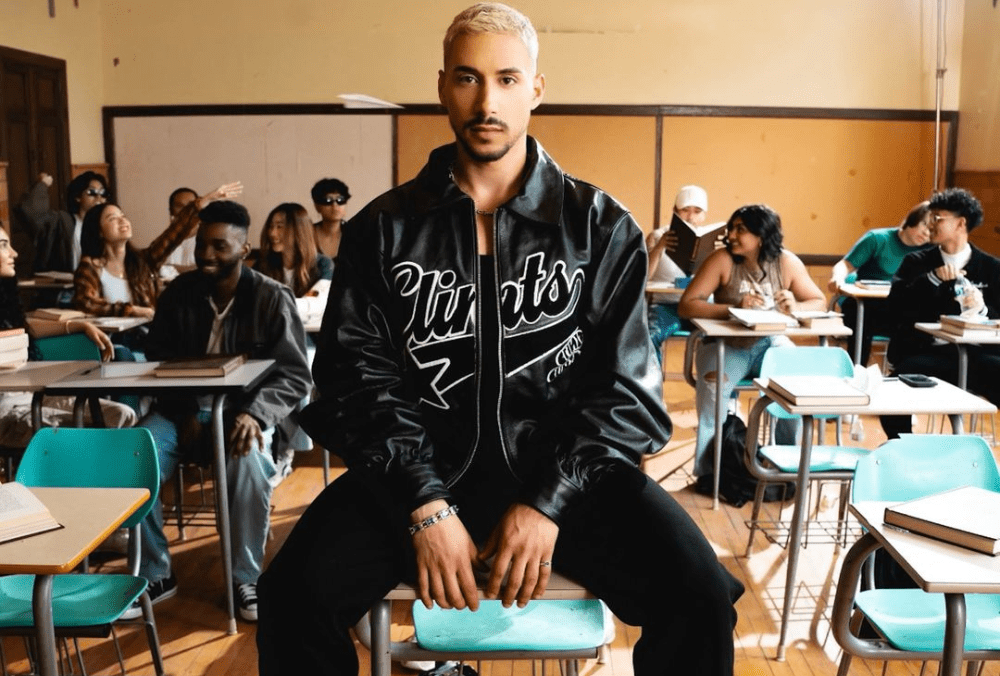

Take I Like the Way You Kiss Me, by British-Cypriot musician Artemas Diamandis, who performs as Artemas. The two-minute burst of pulsating, icy synth-pop – depicting an objectified and emotionally disengaged love affair – has been sticking out a mile in the charts next to Sabrina Carpenter, Kendrick Lamar and the ranks of earnestly strummed acoustic guitars. “We made the song in about three hours, I posted it the next day, then things went crazy,” he says. On release in March it leaped to No 1 in numerous countries and on Spotify alone it has had over half a billion streams – and is just one of many mega-streamed songs in a similar ilk.

An official Spotify playlist of artists featuring the likes of Artemas, Mareux, Boy Harsher, Ekkstacy, ThxSoMch, Twin Tribes, the KVB, Molchat Doma and Pastel Ghost – along with older groups like the Cure and Depeche Mode – have been bundled together under the label of darkwave. But while it’s unquestionably one of the most popular genres in the world at the moment, nobody can agree on what exactly it is or whether they fit into it.

“It’s hard to say what darkwave is,” says Carter De Filippis, AKA ThxSoMch, whose 2022 track Spit In My Face! also broke the half-billion streaming mark. “Artists, especially nowadays, we’re not really thinking of genre when making music. We’re just pulling from things we like and the music from the past kind of becomes music of the future.”

Diamandis agrees. “The romantic in me wants to have a specific sound,” the 24-year-old says. “All my favourite acts from the past do, but it’s really hard for artists of my generation to have that because we have such scattered tastes. We don’t really have scenes, we just have playlists and an endless supply of music.” While Khyree Zienty, AKA Ekkstacy, says: “I’ve never been good at putting a name on my music. It’s hard to do without sounding like an asshole.”

Helpfully, a new 60-track compilation album No Songs Tomorrow: Darkwave, Ethereal Rock and Coldwave 1981-1990, has arrived to provide some historical context. Featuring the likes of the Cure, Dead Can Dance, Cocteau Twins, In the Nursery, and Twice a Man, it shows that even in its original form, darkwave has always been a blurred genre. Simply speaking it’s an exercise in opposites: taking new wave, keeping it uptempo, but inverting it to something more minor key, introspective, alienated and, well, dark.

If there’s one single band that most neatly embodies darkwave in its original cross-pollinated form, it’s Clan of Xymox, whose 1985 self-titled album on 4AD remains a template album for music that is as brooding and melancholic as it is quietly euphoric and dancefloor ready. “John Peel declared we were the pioneers of darkwave,” says Ronny Moorings of the band, who has seen their influence in the current wave of groups via remixes from Twin Tribes and covers from She Past Away. “Darkwave is totally hip at the moment,” he says. “Newer bands always say we were inspirational to them but I also get inspired by their music – it’s a perfect cycle.”

All-female German band Malaria!, another 80s act featured on No Songs Tomorrow, harnessed the edgier end of post-punk but with added synths and hooks. “I was always interested in the brain and the body,” says the band’s Gudrun Gut. “The body was the drums, and the brain was the synthesiser.” Gut says interest in her old band in recent years has spiked. “A lot of very young producers and musicians, especially women, reference Malaria! a lot,” she says. “We were role models.”

Both Gut and Moorings, and the music they made, stemmed from a rejection of conventional living and mainstream music. Moorings was living in squats in the Netherlands – one of which burned down while he was in it – playing gigs in abandoned factories. “It was a free state and we could do whatever we wanted,” he recalls of the time. Gut says her music was a reflection of the “wild, extreme yet grey” backdrop of West Berlin, which was made up of a community of likeminded “art lovers and partiers”. Gut was even in the earliest incarnation of Einstürzende Neubauten, a band who rejected the gloss of the era perhaps more vehemently than any by pilfering from building sites to make instruments, recording music under motorways, and drilling through walls at shows.

However, the through-line from 1980s music into the new crop of gen Z artists is not straightforward. Both Diamandis and De Filippis cite Nirvana, grunge, and Soundcloud rap, as well as the avant-electro of groups such as Crystal Castles and the shimmering neon pop of the Weeknd, as being more key to their foundations. Diamandis’s primary association with 80s artists came more from when his mum told him his music sounded like that, and so he went back to explore.

The likes of Boy Harsher and the KVB, who have been around for more than a decade now, have seen their streaming numbers and live audiences grow rapidly amid this fresh surge. “The main difference with new bands coming up now is the influence of the club,” says one half of Boy Harsher, Augustus Muller. “Club culture is much more prevalent, especially in the States. The first raves we played were all DIY spaces and there were a lot more live sets than DJs – just, like, a 707 [drum machine] into a Boss distortion [pedal] and some guy headbanging. Now there’s lots of proper clubs with nice sound systems and Berlin is a household name. People are going to adapt to where they imagine their music playing and that has a major impact on the sound. We’re writing more for the club these days, and less for the old chemical factory in North Philly.”

Kat Day of the KVB says that “music production becoming more democratic with digital audio workstations and cheaper synths” has helped. “At its heart, the darkwave scene is absolutely DIY. They are bedroom-written and produced songs which, with the internet, have the power to traverse borders.”

Spotify’s patronage aside, there’s also a feeling that this is organic and fan-driven. “Artists have built followings without a big-budget PR campaign or expensive studio recording sessions,” says Day. She also wonders if the appeal for younger listeners is “a kind of rebellion towards music not pushed by the masses or that is overly commercialised,” she says. “The songs themselves are not over-polished, have a lo-fi aesthetic, and are maybe an antidote to the overly perfectionist social media worlds that this generation grew up on.”

This seems to ring true for the younger generation who are making the music. “I was just doing this in my bedroom and then I’m getting a million streams a day,” says De Filippis. “It’s like, how is this happening? I think people are gravitating towards it because it’s so easy for everything to be digital and clean. I like it when things are a little grimy.”

Throw in the wildcard era of TikTok and even more songs are seemingly exploding from nowhere. Back in 2015, Mareux covered the Cure song the Perfect Girl, but it would take six years for it to blow up on social media after people started placing the song over cuts from the film American Psycho. Similarly, the Belarus outfit Molchat Doma, signed to the relatively cult underground label Sacred Bones, got huge when their music began to accompany a TikTok fashion challenge, as well as numerous Soviet-era videos of brutalist architecture and the like. Soon the brooding sound of their track Sudno (Boris Ryzhy) was being heard by hundreds of millions of people.

While TikTok trends come and go, the music appears to be lasting. “People say our music resonates with them because of its honesty and sincerity,” says Raman Kamahortsau of Molchat Doma. “In our songs, we convey the dark side of a person – the depressive, sad, and anxious moments.”

That plays out in Artemas’s I Like the Way You Kiss Me, whose lovey-dovey title is rather undermined by its brutally honest chorus: “Not tryna be romantic, I’ll hit it from the back, just so you don’t get attached.” Diamandis says this unabashed, unpolished lyricism is resonating. “I would never say some of the stuff in conversation in real life that I sing in my songs,” he says. “But there’s something about singing it in a falsetto over a hard beat that’s quite freeing. Once people know that I don’t take myself too seriously, and maybe know more embarrassing things about me, I just find it much easier to relax and breathe.” De Filippis says his tracks are “a way for me to make darker, more melancholy music that I can still move around to while still being true to myself”.

Whatever the appeal of darkwave, millions of fans have gathered under its broad umbrella. Diamandis speaks to me in the middle of his first ever tour, and the next one booked for later in the year is in venues quadruple the size. “Before this I’d only played shows to 20 people in a room,” he says. “I guess that’s just how things move with virality these days – once people decide that they want something, that’s it.”

No Songs Tomorrow: Darkwave, Ethereal Rock and Coldwave 1981-1990 is out now on Cherry Red Records