‘Have the courage to walk away’: Bon Iver on romance, retirement and his rapturous new record

Justin Vernon would rather not be doing any of this. Releasing a new Bon Iver album, promoting it. He absolutely isn’t going to tour it. “I don’t need to do this any more,” he says. “I want to be done with this whole thing. But I am dead serious about these songs. That’s how much I care about them, that I’m going to do something I haven’t been comfortable with to put them out.”

As soon as Vernon hit the public eye in 2008, he started pulling away from its obsessive glare – and from the caricature of him as the lonely woodsman who made his era-defining debut, For Emma Forever Ago, in a hunting cabin in his native Wisconsin. His sound grew cryptic and mutated, though he was no less popular for it. Kanye West and Taylor Swift wanted to collaborate. But anxious from the demands to flay himself for entertainment, he clouded his image. He intimated that he would retire, which only created more distorting attention. As Vernon puts out his first album in six years, he knows better than to make such declarations, though he “might peace out” after releasing Sable, Fable.

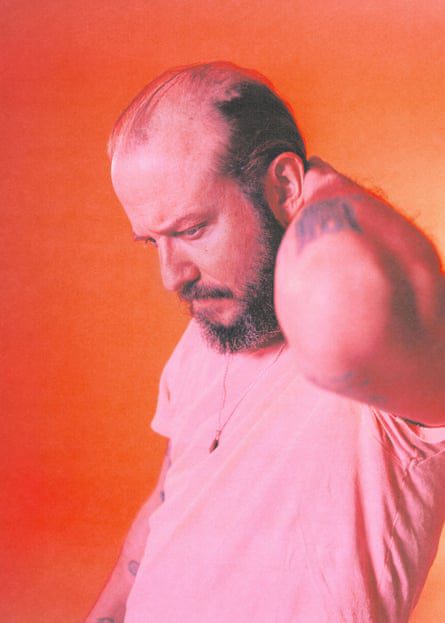

If he is going to give these pivotal songs a chance, he wants to go all out. As well as an album, he’s selling a salmon-hued – to him, the colour of life – T-shirt bearing the image of a giant salmon, plus a tinned smoked salmon collaboration, and a fragrance (not salmon). “I’m not gonna hide my face any more,” he says. “I’m gonna be out here full-bore, full-scene. I wanna see how bad it feels.”

It’s why the 43-year-old songwriter is sitting cross-legged on my sofa in north London in mid-March. He’s kicked off his “footies” – hand-sprayed in salmon – freeing the ankle he recently sprained playing basketball. Wearing a blue hoodie advertising a hometown brewery, he relays the dark and light of his past half-decade with dude-ish enthusiasm and ease.

Sable, Fable documents a period when what had felt like irrevocable darkness became light. The Sable part arrived as a three-track EP last autumn: lovely, straightforwardly sad songs about hitting a wall. “I wanted to try to be basic,” says Vernon. The last of the three, Awards Season, is a pivot, as new love enters his life: “You can be remade,” he sings. The revelation invites the radiantly funky secular gospel of nine infatuated songs that make up the remaining Fable part of the album, made with Jim-E Stack and, often, Danielle Haim. The lyrics have strikingly simple repeated internal rhymes, like nesting dolls. “I just want it to feel good and feel happy,” says Vernon. “To have a song about sex where the only way to listen to it is to move rather than be like, let me introspect.”

Vernon wrote Everything Is Peaceful Love, Fable’s centrepiece, in 2019. It has a beautifully silly chorus that crests like a sunrise: “Damn if I’m not climbing up a tree right now!” – childish ecstasy meeting the fear of what you do once you get that high. “It was almost like, I feel so good I don’t know what to do,” says Vernon. He wanted to harness that mood. “We put it on the wall to see what else gathered around it.”

The feeling was mostly aspirational. Then, the future really “looked like a brick wall that I didn’t have the mechanics to go around”, he says even‑handedly. “I didn’t have suicidal ideation, but I remember telling my therapist: if a bus hit me today that would be a fucking relief.”

Vernon’s body had been “buzzing with anxiety for a dozen years”. After his massively successful debut, making 2011’s Grammy-winning followup Bon Iver, Bon Iver, was almost a lark. “It was so funny to me that we had blown up so hard. It was almost like I couldn’t lose, so I had all that courage: y’all are crazy. I’m gonna do a record where it starts out like metal and ends as 80s sex rock.”

But by the time Vernon got to the symbol-laden 22, A Million in 2016, he was “struggling with not really having anything new to say”. Profound anxiety meant he cancelled a European tour: “I couldn’t even leave the house.” Performing drained him. “Not to say I’m special, but some of my music, you have to get down in there to find the source, to actually speak the music,” he says. “That’s a mechanism like anything else. It breaks down and needs recuperation, and it just wasn’t getting enough.” He managed to “get back in the groove” for 2019’s expansive i, i. His mental health was “patched together, and I loved the touring family so much”.

The pandemic soon prompted Vernon to ask himself some “hard questions” about the future. He was back in the Wisconsin woods again, and wrote the incantatory Things Behind Things Behind Things. “I would like the feeling / I would like the feeling / I would like the feeling gone / Cause I don’t like the way it’s / I don’t like the way it’s / I don’t like the way it’s looking,” he sings. “It was like, this feeling sucks,” he says, dejected. “Kind of prayering it out, summoning it so that you could throw it in the wind and have it blow away like dust.”

Still, Bon Iver got back on the road in 2022. “I was excited for about a week, then immediately started having this panic, exhaustion.” He felt trapped until the tour ended. In September 2023, he definitively sold or donated all his live gear: “If I didn’t, I was almost afraid that I could get pulled back into it accidentally.” He still felt unwell for another year.

There was one immediate improvement: he attended a five-week programme to quit smoking. He had started in his mid-20s while working as a chef, which he hated. (Quitting that, and his then-band, brought Bon Iver into being.) It worked: Vernon replaced smoking with nicotine toothpicks, which he tweaks as we talk. It was another “big brick wall”, he says. But this time, “all the good parts of me kept going and all the shitty parts kind of hit that wall.”

Smoking became a metaphor for other ways Vernon wanted to better himself. He asked: “What validation was I getting from being this sad, bruised boy? The attention came to me and of course I’m going to react, like: I’m worth it, or something. Then, subconsciously you steer towards a little more self-destruction.”

Vernon questioned whether fame and his fried system had made him a “shithead”: a bad brother, boyfriend, friend. “I don’t really want to talk about Kanye,” he says – having worked on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Yeezus, long before the rapper’s heel turn – “but it’s a good example of observing when people have their head up their ass a little bit, or they’re so busy, and so needed, that you start getting soft.”

He concluded that his problems weren’t “that hard”. If touring was the problem, then “Just stop it,” he says. “I know there’s a lot of pressure on you, but the answer is either yes or no, and if it’s no, you better get the fuck out of here because you can’t keep acting like this. I could see the quality of my character slowly diminishing from trying to be too much to too many people.” He believes the world needs more hard decisions. “My buddy Trevor says: ‘Hard decisions, easy life. Easy decisions, hard life.’”

Vernon faced that scenario again with the new love he sings about in Awards Season. “I wasn’t feeling too good about myself, and this person made me feel really good about myself,” he says. “Like everything I had done to this point had been OK.” Then came the classic next step: “Let me just give you everything. I need that feeling. Please give it to me constantly.” He had to pull back from the relationship. “Where’s the personal growth? How much can you depend on another person? What parts of me are just rushing to conclusion?”

Vernon says that the relationship is neither over nor ongoing, “and I don’t mean to be vague”, he says. “This person is a central part of my life. But it wasn’t in the cards to be like, now we’re together.” That’s the Fable part: “Little lessons about what happens after that” – messages he’s still getting from the songs. His favourite is the gleaming benediction There’s a Rhythmn. “It says: I don’t know what’s gonna happen. It might not matter whether we’re together or not because you changed me for the better. We shouldn’t squander what didn’t happen. We should just be thankful for what we do have.”

after newsletter promotion

The experience overhauled his idea of relationships. “Since I was eight years old, I could not wait to get married,” he says. “And here I am, 43, far away from that being a possibility, which saddened me for so long. Growing up with such a strong family, every day since I left the house at 18 was kind of a letdown. So was I looking for that relationship because I wanted to have that peace? I have to make that for myself before that can ever happen.”

Fittingly, when Charli xcx asked Vernon to appear on her Brat remix album last year, he refashioned I Think About It All the Time, about whether career and motherhood are incompatible. “What she’s talking about in that song, like, I’m always two steps ahead of myself, it was really easy for me to react to that,” says Vernon. “It was great timing because it felt like a coda for all the lessons I’ve been learning.”

Vernon might be technically middle-aged, but he’s stopped feeling as if he is running out of time. “I’ve done enough personal work where now I feel young,” he says. “When I was 33, I was like, oh my God, I’m gonna die soon – like, life is short. But now, I’ve got my health. I feel like I’ve got a lot of years to live. To be able to say that and feel truthful, I feel like I really overcame some shit.”

He knows some listeners might hate this sea change: after all, everything today is not exactly peaceful love. “I’m not really afraid of that,” he says. “I know that I need to do this for me. I would hate to think it feels like a distraction or that I’m ignoring the problems of the world to sell myself. But I give myself permission to put this kind of art into the world because it is about love, and we’re animals out here.”

Days before Sable, Fable’s release, I speak to Vernon again: he has just flown to a cottage he’s been renting in Los Angeles, where he’s been splitting his time, after seeing Bob Dylan play Eau Claire at the weekend. Dylan was apparently in the mood to play It Ain’t Me, Babe in the style of Irving Berlin’s Puttin’ on the Ritz. “I didn’t like it? I wasn’t having a good time?” Vernon says over a video call, questioning himself. “And yet, every time words start to come out of my mouth, I’m like, you don’t need to say anything about it! The guy is a free fucking spirit.”

In LA this week, he has a few more promotional duties, including hosting a basketball tournament. (“I bought ankle braces today.”) A month of being “full-bore” turned out to be all right. “I barely recognise myself,” he says, reclining in a black T-shirt. “I don’t think I would do this for ever. I don’t know if I’ll do it again. To have really given myself a gift – to not be getting ready to do the whole touring rigmarole, and to have been present enough to talk about something that I worked hard on for a super long time – has been really rewarding.” His system finally feels calm and reset. Friends have noticed the difference. “They’re like: ‘You seem good,’” he says.

As much as Sable, Fable reflects a radiant period, it also, fundamentally, emerged from depression, as did all Bon Iver records. Vernon has been learning to handle it differently. “I haven’t had a bad day since New Year’s,” he says. Back then, for the second year running, he was ill, home alone and miserable. Then his friend Aiden suggested: “‘How about 2025 – no defeatism?’ It was like a switch went off,” says Vernon. “What the fuck have I been doing? What do I have to feel sad about?” With any anxiety since, he says, “you notice it, you absorb it, you consider it and you breathe through it”.

Vernon hopes that anyone initially drawn to the lonely woodsman of For Emma might find similar solace in Sable, Fable. “Running away to a cabin is very powerful because it’s an example that you can choose to do anything,” he says. “That’s the crazy part of having any freedom in this world.” Quitting touring or accepting a relationship’s end is no different. “In There’s a Rhythmn, I sing: ‘Get tall and walk away.’ Have the courage to walk away from something that seems to be the greatest thing on Earth, but it’s not serving you. Have courage to do something bold, not just for bold’s sake, but because you have the patience to locate what’s wrong.”

It didn’t initially dawn on him that both Sable and Fable contain the word “able”. If the album is about aptitude, he says, it’s: “Can you conceive of having the strength to move forward?” Next he might start a new group, make an album with Tobias Jesso Jr, reunite with Hadestown’s Anaïs Mitchell (who cast him as Orpheus in the original album) or create “a secular music church with the greatest sound system in the world”, he says. “What can I take from what me and my team have accomplished to break down the format of this tired thing that is touring? I’m in my early 40s. It’s a good time to still be young and to try to rattle the cage.”

It’s why he can’t diss that weird Dylan show. “This motherfucker is not of this planet. And just because I was uncomfortable with everything musically, I still watched something real, at least.”

Vernon thinks he has now taken all he can from Sable, Fable. “It makes me quite emotional, because it’s therapy,” he says. “It’s me constructing this giant map and then staring at it, and the wind is about to blow it away and then it will be for everyone else.” It’s another fable: just because a moment might not last, doesn’t mean it’s not meaningful or worth doing. Vernon had resisted being Bon Iver again, but he’s showing up for it, for love. “That’s it,” he laughs. “That’s what I’m trying to do.”

Sable, Fable is out now on Jagjaguwar