‘You got it or you didn’t’: the sweat, smoke and sonic excess of the indie scene pre-Britpop

A while back, photographer Joe Dilworth found himself talking to the drummer in a currently successful British rock band. He asked how they got started, expecting to hear about low-rent gigs, and was startled to find the drummer talking about their business plan. “He told me they’d got loans, from their parents I think, and they paid themselves 20 grand a year until they got signed.” Dilworth laughs. “They’d treated it like a startup. They’d viewed playing small gigs as a kind of loss leader.”

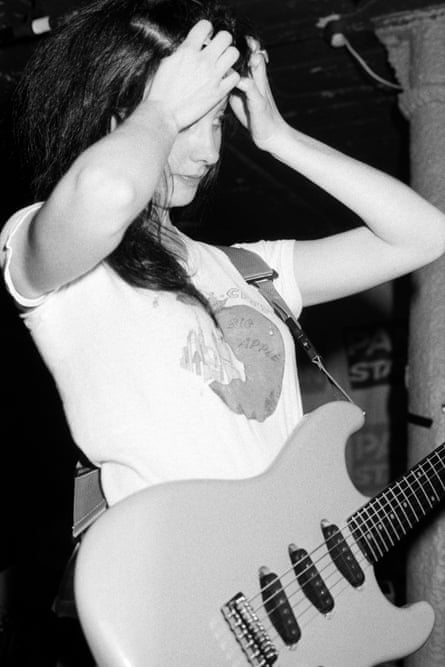

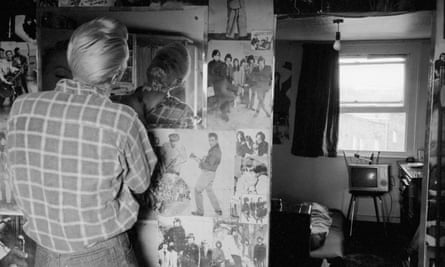

It was a conversation from which you could infer a lot about the state of music in the 21st century, but it got Dilworth thinking about the bands he’d photographed in north London in the late 80s and early 90s: pictures of tiny, unruly gigs (“the band were always in cigarette-lighting distance of the audience”), dingy pubs, and what you’d politely describe as rudimentary living conditions. These are now collected in a book, Everything, All at Once Forever.

Some of the bands ultimately went on to cult success, hailed as an inspiration by other artists, My Bloody Valentine and Stereolab among them. Some enjoyed a brief moment of music press notoriety before fading away, including Silverfish and Th’ Faith Healers, with whom Dilworth drummed. Some had a subterranean profile even at the time: it would take a very enthusiastic scholar of indie obscurity to recall Sun Carriage or the Charity Case.

But regardless of how they ended up, it seems safe to say that no one in their right minds – not even the wealthiest, most devoted parent – would have considered investing thousands in them. As Dilworth points out, none of them sounded much like each other. There wasn’t much to link Stereolab’s hypnotically repetitious, Krautrock-and-vintage-electronica-inspired sound to the lurching, combustible din of Silverfish, with their fearsome frontwoman Lesley Rankine, and their songs called things like Total Fucking Asshole, Shit Out of Luck and Don’t Fuck – beyond the fact that all of them represented challenging listening in one way or another, way outside even alternative music’s mainstream. In 1988, the NME’s bankable cover stars were the Pogues, the Mission, Morrissey and the Wonder Stuff.

Dilworth joined Th’ Faith Healers after witnessing an early gig at indie haunt the Camden Falcon, during which the pub’s landlord rushed in and started trying to unplug the band’s equipment, desperate to make the racket stop. Today, My Bloody Valentine are regularly hailed as one of the most innovative and influential guitar bands of their era, but Everything, All at Once Forever captures the shock of encountering them in a tiny venue around the time of their breakthrough single You Made Me Realise.

It contains photos of a 1988 show at Dingwalls that degenerated into chaos when the venue’s soundman simply gave up trying to deal with band’s trademark sound – drowsy melodies submerged beneath an ear-splitting wall of churning noise – and walked out mid-set. “The setup just couldn’t handle it,” says Dilworth. “It wasn’t designed for what was happening. Their sound was something you either got or you didn’t – and no one was going to break it down for you.”

But the thing they really had in common was a lack of expectation, an almost complete disregard for commercial success. Forming a band like that in the late 80s, Dilworth laughs, “was declaring yourself a total loser, actively saying that you were wasting your life”. With the benefit of hindsight, he says, it also feels like a statement, a sloughing-off of what he calls the 80s “aspirational culture”.

“If you think about the ads on the telly then,” he says, “it was all selling off British Telecom and British Gas. We were all supposed to be living this yuppie dream. I think it became obvious to people that they weren’t going to be part of any of that, so why not just do our own thing? At that point in the late 80s, deep into the Thatcher years, that wasn’t what you were supposed to be doing. Everything seemed to be either going, ‘Oh, it was much better back then’ or, ‘You’re going to make it and be rich one day.’ But this whole thing was very much, ‘This is it. This is it right now. It’s all about the right now.’”

Then again, no one actually needed to front the bands a loan. The photos in Everything, All at Once Forever capture a lost north London in which everything looks infinitely grimier and grimmer than today: you can almost smell the live photos, the distinctive tang of cigarette smoke, sweat, stale beer and small rooms untroubled by the concept of a cleaning rota that was the grassroots gig venue’s default scent 35 years ago.

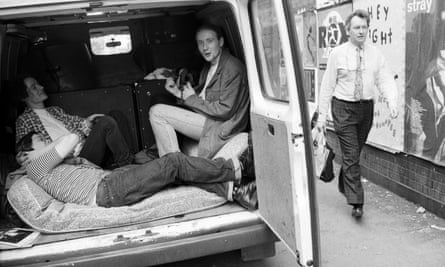

The photos of pubs, meanwhile, speak of a world before guest beers and gastrofication when, in the unlikely event that food was served, actually eating it involved taking your life in your hands. But it also looks somehow more alive and exciting. As Dilworth points out, things were happening in Camden that couldn’t happen now, supported by a preponderance of pubs with music licences, people scraping by on the dole (“the best arts funding the British government ever provided”) and the capacity to live rent-free if you didn’t mind the privations of squatting.

“My Bloody Valentine had been living in Berlin,” he says, “and they moved to London because you could effectively do what they were doing for free. I remember taking a music journalist to their squat in Kentish Town and he was like, ‘They live here?’ You know, you had to climb over a car bonnet to get in the front door. It really was very, very grotty. But it was free.”

The photos tail off around 1993, the year Britpop started to take off, bringing with it a very different attitude to mass appeal and commerciality. In tandem with a series of dramatic shifts in the music industry – and, more broadly, in British society – it ultimately ushered in what you might call the business-plan era of alternative rock. “One of the things that makes it so hard to remember all this,” says Dilworth, “is that what came after was so kind of crushing.”

A couple of bands managed to navigate the ensuing years, Stereolab among them. Most split up or faded away. My Bloody Valentine signed a £250,000 deal with a major label then vanished. They declined to release another album for 22 years, a state of affairs usually held to be the result of a curious combination of perfectionism and indolence on the part of the band’s mastermind, Kevin Shields.

But perhaps it also carries something of the confrontational spirit of the scene that Everything, All at Once Forever pungently captures. “I remember visiting them in the studio,” says Dilworth. “We hung about a bit, went to the pub, came back. I thought, ‘There’s a producer here, the clock is running.’ Kevin was absolutely unfazed, saying, ‘Yeah, I’ve spent this week making a tent for my amplifier out of blankets.’ It was like, ‘If you’re dealing with me, this is what I’m doing.’”