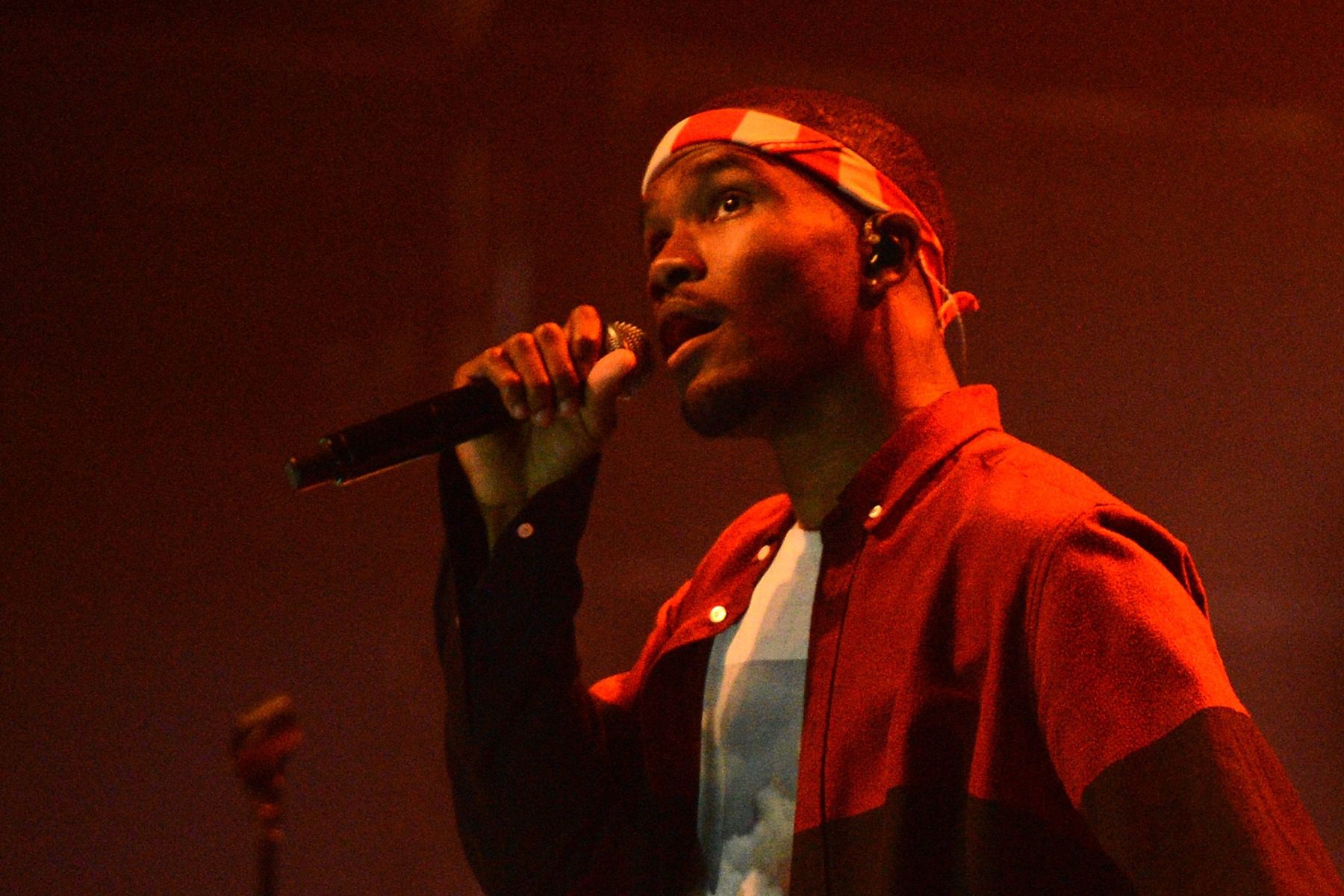

The Radical Openness of Frank Ocean’s ‘Channel Orange’

Released ten years ago today, Frank Ocean’s debut, Channel Orange, stands as a singular achievement in popular culture and a touchstone for a cohort born into the ethics of social media. Frank exhibits the kind of radical openness that would come to define a generation of young people who, like him, discovered their true selves with the help of the internet.

Frank’s lens is crystalline and otherworldly, like the diamonds of Sierra Leone — one of the many locales he brings us to throughout the record — offering a view of heartbreak so honest that it feels universal. The album offers a kaleidoscopic worldview that’s both untethered from time and fueled by a vivid sense of feeling. A familiar story that manages to feel brand new, even a decade later.

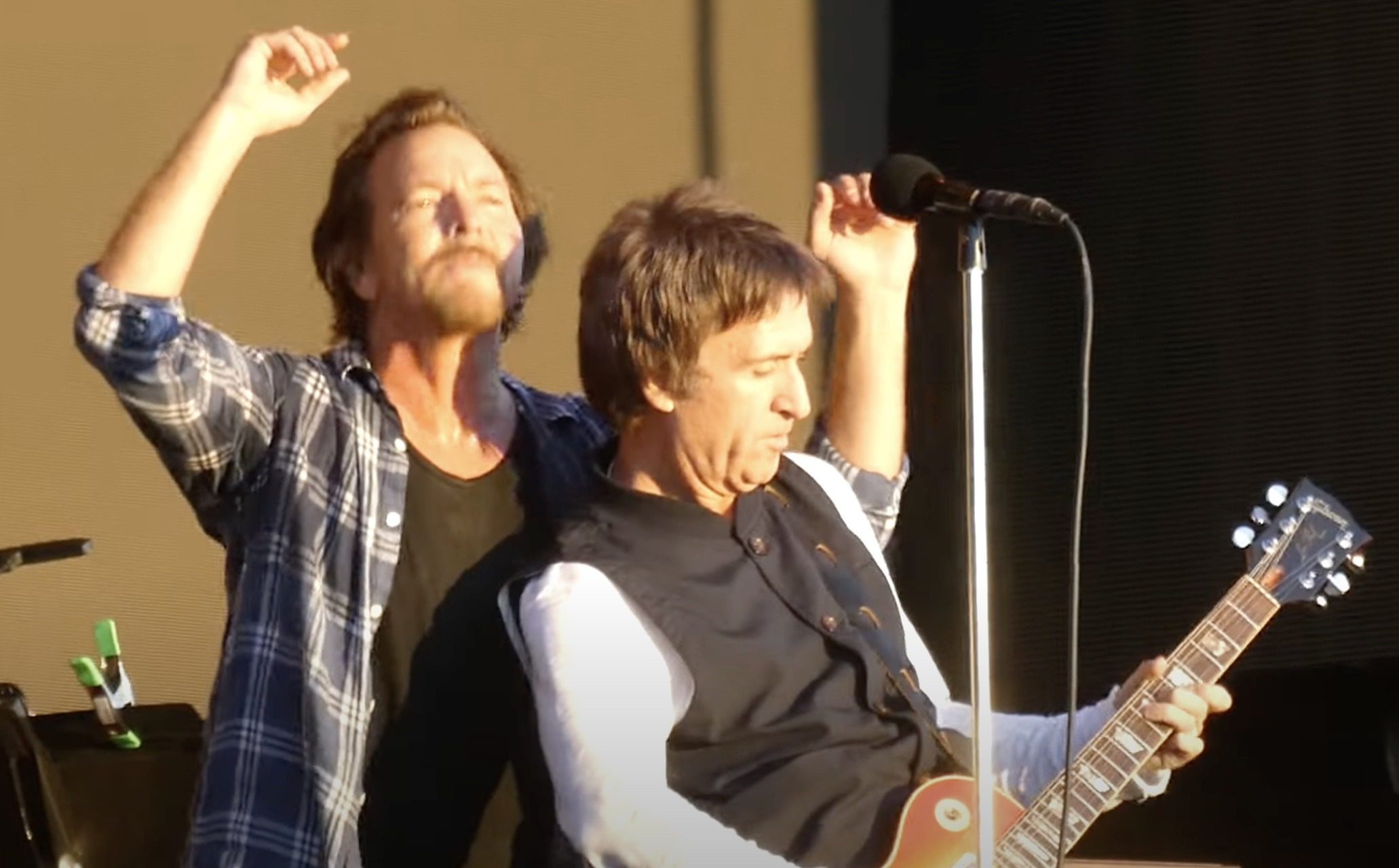

Born Christopher Edwin Breaux in New Orleans, Frank made his way into the mainstream through the crater-sized back door his Odd Future compatriots blew open during the two years leading up to Channel Orange’s release. Already, the Los Angeles-based crew of punk-looking rappers were reconfiguring the contours of not only hip-hop but also of Black life in America. We still don’t quite have the language to articulate the shift brought about by a band of skateboarding Black teens with a penchant for rap music and horror films. OF were far from the first “alternative” Black artists in the mainstream, but the ways in which they wholeheartedly rejected the framework of identity remains novel to this day.

And Odd Future’s genuinely punk ethos matched well with Frank Ocean’s empathic detachment. Throughout his debut mixtape, 2011’s Nostalgia, Ultra, he reveals himself, as a songwriter, to be chiefly concerned with not just his emotions, but with the nature of feeling itself. Frank managed to bring an existential sensibility to R&B, like on “Songs for Women,” in which Frank takes a meta approach to the traditional love song. That kind of radical inquisitiveness pulses through the project, which was released as a kind of “Fuck You” to the reticent major labels unwilling to release it.

Still, it somehow felt more possible, in the optimistic glow of the 2010s, for an artist like Frank Ocean to thrive. Not just as an openly queer black man straddling the worlds of hip-hop and R&B, but also as an artist committed to a literary understanding of his life. Frank’s worldview doesn’t arrive in the split-second vignettes that typify the current generation, but in layered and subtle textures that, a decade on, lend themselves to new prisms of understanding.

The delicate pronoun wordplay in “Thinkin Bout You,” for example, has a way of obliterating any notion of a gender binary, fusing the colloquial and personal “boy,” into something of a subconscious missile. The song relies on a mischievous repurposing of language. In the second verse, as though delivered with a sly wink, Frank takes a bygone lover to task. “No, I don’t like you, I just thought you were cool enough to kick it/Got a beach house I could sell you in Idaho,” he sings. I still remember the feverish sessions dissecting the album’s lyrics back in 2012, explaining to anyone who’d listen how Frank was employing a poet’s flair for wordplay. “Since you think I don’t love you, I just thought you were cute/That’s why I kissed you,” he continues. “Got a fighter jet, I don’t get to fly it though, I’m lying down.”

While the follow-up, 2016’s Blonde, arguably outshined Channel Orange in scope and impact, Frank’s debut offers a rare look at one of this generation’s most honest voices coming into his own. On the Earl Sweatshirt-assisted “Super Rich Kids” an interpolated sample of Elton John’s “Benny and the Jets” guides us into the world of Black wealth in Los Angeles. Here, Frank is in new terrain. He explained to GQ around the album’s release that, despite chatter online, the song was not inspired by his own life (“We were not middle-class,” he said. “We were poor.”) But fan confusion here is instructive, throughout Channel Orange, Frank is able to embody experiences with a lived-in clarity. On “Crack Rock” we’re in the middle of Arkansas, with a “little rock left in that glass dick.” Like a line out of a Hunter S. Thompson novel, a momentary image captures a lifetime.

“Pink Matter,” maybe the album’s best track, grapples with the very nature of human sexuality. Flesh and evolutionary functions tussle for supremacy until Frank, in his way, brings it home. “Nothing mattered/Cotton candy, Majin Buu.” Andre 3000, in one of his best guest verses, matches the song’s concern with ennui. Andre floats above the already ethereal beat, contemplating his own relationship to sexuality. “I’m building y’all a clock, stop, what am I, Hemingway?” he raps. “She had the kind of body that would probably intimidate/Any of ’em that were un-southern, not me, cousin.”

On the daringly experimental “Pyramids,” Frank glides from biblical mythology to the strip club, expounding a view of womanhood that stretches through time in a way that makes the past and present feel less like distinct points and more like a singular experience. Almost like the multiverse narratives that today dominate pop culture, Frank Ocean found a way to bring a view of the world as vastly and beautifully interconnected into the mainstream. His famous Tumblr letter, in which he elegantly and tenderly tells the story of falling in love with a man, opens with what, ten years later, feels like a genuine statement of purpose. “Whoever you are. Wherever you are…I’m starting to think we’re a lot alike,” he wrote. “Human beings spinning on blackness. All wanting to be seen, touched, heard, paid attention to.”

The world today feels terrifyingly distant from the one in which Frank released his debut. It makes revisiting Channel Orange today feel tinged with an amalgam of grief and hope. Something about today feels like a regression, but more than anything Channel Orange makes the case for seeing the passage of time in less linear terms. Rather than see our current troubles as a unique point in history, we can view them as part of a larger mosaic. Channel Orange starts and ends with the sound of a TV switching stations, and creates a near-hypnotic loop. What feels like the end is almost always just the beginning.