‘Rock and Roll Is at Its Most Beautiful Stage When It’s Free’

Paing Mhu Ko Ko/Vilane Photography

‘Rock and Roll Is at Its

Most Beautiful Stage

When It’s Free’

In Myanmar, a military coup ripped away rock musicians’ glimpse of creative freedom. Faced with a return to repression and censorship, they are finding ways to fight back

Four rock musicians met secretly at an abandoned house in Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar. It was March 7th, just over a month after the country’s military had seized power in a pre-dawn coup, and they were there to record a song about security forces shooting to kill. They called it Headshot and the chorus went:

Give us back our democracy. Now!

Release every innocent one you captured. Now!

Whose power was taken away? Ours!

We, the people, have the power

Down with the military regime, the war-dogs

Biting the hands that feed them

The song was a cry against the living hell that descended upon the people of Myanmar since February 1st, when the military overthrew the country’s civilian government. It was also a song of solidarity with the people killed while standing for democracy. And it was a song of mourning for freedoms barely tasted that were stolen overnight.

“We witnessed people get shot and killed right in front of us,” Han Htue Lwin, who goes by the stage name Kyar Pauk and is one of Myanmar’s most well-known rock musicians and producers, tells IndieLand. “We were like, ‘We’ll record one song and then we’ll split after that,’ because if we recorded that song, it would give us enough danger to split up.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody1-uid0’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article”,”mid”,”in-article1″,”mid-article1″] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody1”)

.addSize([[300,250],[620,350],[2,2],[3,3],[2,4],[4,2]])

;

});

That night in Yangon was the last time the rockers made music together. Within hours of releasing the song, the rockers scattered. Three of them were later placed on a wanted list for sedition, their names and photos shown on the military-run TV channel. By June, they’d be irreparably separated.

Kyar Pauk has since fled the country. Han Nay Tar, lead singer of Eternal Gosh, an alternative and pop rock band established in 2013, has gone deep into hiding and couldn’t be reached. Novem Htoo, among the country’s most famous metal vocalists, has sought shelter with an ethnic armed organization. Raymond, lead singer of the band The Idiots and among Myanmar’s most influential rock musicians of this generation, had been staying in the jungle with Novem Htoo, but on June 23rd, the 32-year-old, who had long suffered from gastrointestinal problems, was found dead.

Until the coup, Kyar Pauk’s career had been going well. In late January, he and his band Big Bag were on the cusp of a record deal with a new label, and he was discussing an electronic project with Raymond. There were struggles, including the shutdown of live performances due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but he was finally able to make the music he wanted.

Since the democratically elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi came to power in 2016, Kyar Pauk had experienced freedoms that were unthinkable when he had started making music in 1997.

During nearly five decades of military dictatorship, the generals had kept a close hold on power, even when it meant resorting to violence. In 1988, regime forces responded to student-led pro-democracy uprisings with a bloody crackdown that saw thousands killed and imprisoned; protests initiated by saffron-robed monks in 2007 were also met with deadly force.

For artists, the former military era came with a heavy dose of repression. Musicians needed to apply for studio licenses, which enabled the regime to trace what was recorded and where. And a censorship board screened art, music, cinematography, journalism, and literature prior to publication. It restricted anything hinting at Western influence or opposition to military rule. Even paintings with too much red — the color of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy — evoked suspicion, Kyar Pauk says.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-article-inbody2-uid1’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid-article2″,”mid”,”in-article2″,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbody2”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[620,350],[2,4],[4,2],[3,3]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Beyond censorship, the generals’ approach to running the country stifled the development of a robust music scene. A stagnated education system meant most musicians learned through informal means, Shwe Gyaw Gyaw, who has been writing and producing music since the 1980s, tells IndieLand. “Myanmar has many talented musicians who for decades couldn’t learn music systematically,” he says. Meanwhile, weak rule of law left copyright infringement commonplace, making it difficult for even the most talented musicians to earn a living through music production, he says. Technology also lagged: Myint Zaw, one of the first audio engineers and producers to mix music electronically, was only able to access computer engineering systems for audio recording beginning around 1998.

The former military regime sought to kill creativity, the musicians say. Foreign rock and pop were banned as “cultural pollution,” and the overwhelming majority of songs were covers of Western hits with innocuous lyrics. “We only had love songs and a bit of hate songs about love and relationships. We couldn’t talk about society or criticize the junta,” says Kyar Pauk. In 2008, the censorship board blocked his entire album because the songs were in English.

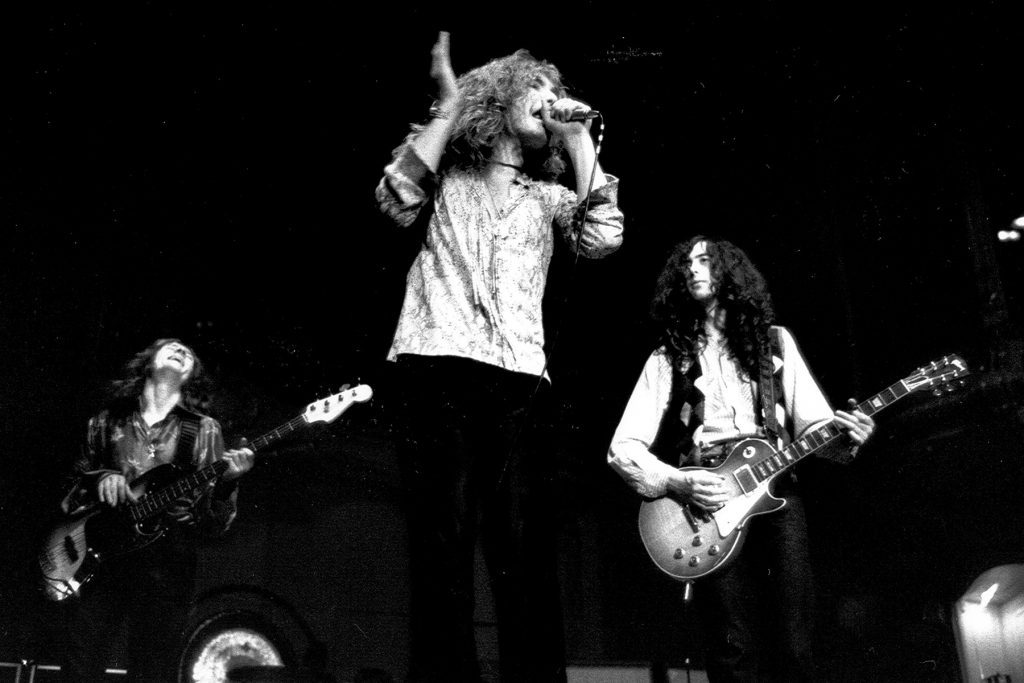

Kyar Pauk and Raymond perform at a protest in February 2021.

Paing Mhu Ko Ko/Vilane Photography

Authorities also imposed random acts of intimidation. In 2006, Kyar Pauk was banned from performing for six months because he gave a free live show with foreign musicians without informing authorities, even though according to the law, free shows didn’t need advance permission. In 2009, he faced another six-month ban on performing because he donated medicine to an HIV clinic run by the National League for Democracy.

But Kyar Pauk was determined to outsmart the regime — for example, by bleeping out provocative words that he knew his fans would grasp through the context. “We needed to tiptoe around [the censorship board] just to pass the message to the people, to our fans,” he says. “We needed to train our brains to pass them, to write in a way that the censorship board couldn’t get it, but my fans would.”

In 2010, while Myanmar hung on the precipice of a political transition, Novem Htoo, currently lead vocalist for the metal band Extant, was also on the edge of an artistic breakthrough.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid2’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

At the time, Myanmar’s mainstream music scene was limited to pop and rock, but Novem Htoo, who had spent his troubled teenage years listening to pirated tracks from Slipknot and Limp Bizkit, decided to push the limits. Lacking mobile internet, he began studying metal videos on YouTube at internet cafes. But in spite of his best efforts, he faced barriers. “I needed to learn to scream,” he says. He also had to choose his lyrics carefully to avoid offending authorities. “Sometimes it made our brains drain,” he tells IndieLand.

In 2010, in line with a plan it called the “roadmap to democracy,” the former junta held sham elections, which saw the military-backed party come to power. The following year, the new government began initiating a series of political reforms.

Pre-censorship ended in 2012, and in 2013, the price of SIM cards, which had been kept prohibitively high, dropped hundredfold, giving the general public ready access to mobile internet. “We could taste new bands,” says Novem Htoo of that time. He rose from performing on neighborhood streets to becoming lead singer of Myanmar’s top metal band, Nightmare, which produced its first album in 2014.

In November 2015, the country held openly democratic elections, and the National League for Democracy won in a landslide.The military-drafted 2008 constitution left the civilian government sharing power with the military and also barred Aung San Suu Kyi from serving as president, but she took the role of state counsellor, leaving her the effective country leader.

The following years saw a further, though flawed, political opening, accompanied by an explosion of artistic creation. “We didn’t need to care about the lyrics, and we could write whatever we wanted,” says Novem Htoo. “We could focus our minds completely on music.”

But for Kyar Pauk, years of writing under censorship left him struggling to acclimate. “I had to train my brain to think freely without any interruption,” he says. “I had no idea what to do and how free is free … We had to test, poke around, and then I think around the end of 2014, we were like, ‘OK, shit, this is great!’”

Once the feeling of freedom sunk in, Kyar Pauk ran with it. “The thinking pattern changed. … You could say almost everything,” he says. In 2016, he produced his first uncensored album, We Are Big Bag. “I said everything in it — what I think about society, religion, rights, you name it — everything we hadn’t been able to say our whole lives. I put it in that album; I crammed it in.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid3’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

The musicians interviewed by IndieLand say that despite the fragility of the democratic transition, the blossoming of rock creation was immeasurable over the past decade. “We had so many bands, so many underground artists, so many people with a lyrical sense of genius,” says Kyar Pauk. “Being able to say whatever we wanted was the most beautiful thing in rock music, because rock & roll is at its most beautiful stage when it’s free.”

And then, overnight, those freedoms were gone.

“It was never fully a people’s government, but the last five years were the best of it. … Things developed very quickly, like you couldn’t even believe, and then all of a sudden, it’s not there anymore,” says Kyar Pauk.

In the months leading up to the coup, the warning signs loomed.

On November 8th, 2020, Myanmar held its second national elections since the end of military rule. In spite of the pandemic, voters across the country queued for hours to cast their ballots. Aung San Suu Kyi maintained a loyal support base, and despite her party’s shortcomings, many saw it as the only antidote to the military and hoped that with another five years in power, the party could deliver on its promise to bring constitutional reform and changes that it had not achieved during its first term. When the election results came in, the military-backed party had suffered a humiliating defeat to the NLD, losing by an even wider margin than in 2015.

Protesters make three-finger salutes and hold up banners and posters as they march on February 8th, 2021, in downtown Yangon, Myanmar. Millions have demonstrated across the country in opposition to the military junta, also known as the Tadmadaw, who on February 1st staged a coup.

Stringer/Getty Images

Although independent observers found no major voting irregularities, the military claimed electoral fraud and refused to accept the results, stating on January 28th that it would not rule out a coup.

In the early dawn on February 1st, just hours before the new government was set to be sworn in, soldiers arrested Aung San Suu Kyi and dozens of NLD party members; they also arrested dissidents and prominent NLD supporters, including reggae singer Saw Phoe Khwar. That morning, Kyar Pauk’s manager phoned him, advising him he should immediately go into hiding. Having produced a popular NLD campaign song, Kyar Pauk knew he could be the next one seized. He quickly left home, narrowly escaping police, who arrived 15 minutes after he’d gone.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid4’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

That day was frighteningly quiet across the country, the people in shock. By the next evening, people were banging pots and pans to “drive out evil,” and the day after that, medical workers launched a civil disobedience movement, refusing to work in an effort to shut down the junta’s mechanisms — an effort that has since paralyzed public services across the country.

That day, February 3rd, Kyar Pauk fled Yangon. Demonstrations started on February 4th, in the central city of Mandalay, and by the end of the week, the country’s streets were overflowing with protesters, who by some estimates numbered in the millions. Around a week after leaving the city, Kyar Pauk returned to join the front lines of the protests with Raymond and Novem Htoo.

Initially, Yangon’s streets reverberated with resistance-themed music, dance, and street art, and the musicians were in the thick of it, leading crowds in singing motivational songs and calling for their rights. But the mood across the country darkened as security forces began dispersing crowds with tear gas, rubber bullets, and water cannons on February 8th.

Then, the situation became deadly. On February 9th, the military fired its first live rounds, in the capital city of Naypyidaw. A bullet pierced the helmet of 19-year-old protester Mya Thwet Thwet Khine; she died 10 days later. Security forces opened fire in Mandalay on February 20th, killing two, including the first of dozens of children who have since been shot dead. From there, the violence intensified, and along with it, the people’s will to resist.

By March 3rd, a day when security forces assaulted volunteer medics and gunned down 38 protesters, a local rights group described Yangon as a “war zone.” According to the rights group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) the military has killed more than 1,000 people since the coup, including at least 114 people gunned down on March 27th. The AAPP has also documented more than 7,700 arrests.

Kyar Pauk, Raymond, Novem Htoo, and Han Nay Tar were in the eye of the storm. Four days after the March 3rd killings, they recorded “Headshot” with a broken-stringed guitar and scarce equipment in Kyar Pauk’s deserted house; they mixed the song and released it online the next morning. That night, three truckloads of police broke down Kyar Pauk’s door, but the rockers were already gone.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid5’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Novem Htoo was the first to leave the city. After assuaging his parents with a story that he was going to hide in the French embassy, he shaved his facial hair, covered a tattoo across his neck that read “Spring Revolution” — the name given to the protest movement — with makeup, donned a mask, and set out with his drummer’s ID card. “He’s a long-haired guy. Even though we don’t look the same, the cops didn’t recognize the difference,” Novem Htoo says.

He boarded a public bus and four hours later, disembarked at a roadside restaurant, where a military-imposed 8 p.m. national curfew necessitated he spend the night. “There were many mosquitoes, and I didn’t have any mosquito net. I felt scared, because it was my first experience going to live in the jungle,” he says. The next morning, he resumed his journey, which ended at Myanmar’s southeastern border with Thailand, in the territory of an ethnic armed organization.

Shwe Gyaw Gyaw and Myint Zaw

Courtesy of Shwe Gyaw Gyaw; Courtesy of Myint Zaw

Since gaining independence from Britain in 1948, Myanmar has seen civil war along its borders, as the country’s diverse ethnic people have sought self-determination and rights. Around 20 ethnic armed organizations have been intermittently fighting against the military; the largest of these claim territories where they run their own administrative systems. Myanmar’s military has sought to crush these resistance movements, including with horrific violations of human rights. Their tactics have included indiscriminate airstrikes, the burning of villages, and the use of forced labor, portering, and human shields. As of 2019, Myanmar was also the only country in the world where the military deployed land mines, which are also deployed by ethnic armed organizations to defend their territories; 2020 saw more than 250 casualties to land mines and explosive remnants of war.

When Aung San Suu Kyi came to power in 2016, she pledged to make national reconciliation her government’s first priority, but the next five years saw a faltering peace process and fresh fighting, including some of the deadliest conflict the country had seen in decades. In 2017, the military also launched a campaign of arson, rape, and killing against the country’s Rohingya population in northern Rakhine State, causing more than 700,000 to flee to Bangladesh.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid6’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Myanmar was consequently charged with genocide at The Hague in 2019, for which Aung San Suu Kyi defended the military, badly tarnishing her international image. At the time, many people in Myanmar rallied around Aung San Suu Kyi and dismissed the Rohingyas’ plight. But the military’s killing of unarmed protesters since the coup has initiated a greater public consciousness of its history of rights abuses against ethnic minorities including the Rohingya, and apologies abound for failing to support international justice mechanisms to hold the military accountable.

Since the coup, fighting between ethnic armed organizations and the military has accelerated, while dozens of new civilian defense forces have also emerged to resist military rule. Armed with little but homemade hunting rifles, they have launched ambushes and attacks on military convoys and police stations, killing dozens of security forces. In response, the military has fired heavy weapons into towns, shelled churches sheltering displaced people, and hindered access to food and relief supplies for civilians. In total, 230,000 people have been newly displaced, primarily along Myanmar’s borders with Thailand, India, and China.

Amid this crisis, ethinic armed organizations have sheltered masses of dissidents fleeing urban areas and provided training to urban youth. Like many youth, Novem Htoo said he decided to train with an ethnic armed organization because, with his life in danger in Yangon, he felt it was his only option to fight back against the military regime.

In the jungle, Novem Htoo faced a dramatic change from city life, but a few days after he arrived, he was joined by Raymond, and the time passed quickly. The two began singing and giving speeches to boost the young trainees’ spirits, and Novem Htoo recalls those days fondly. “We met many youth, but they came and went. Sometimes, just the two of us were left alone … we sat on the bed and talked, because mostly there was no [internet] connection. We supported each other emotionally.”

Raymond, whose parents were both prominent musicians, jumped to a national stage in the late 2000s, when he began producing original tracks with his band and hit songs for other artists. Within years, he became a rock icon among the young generation, known particularly for his lyrics and his soulful live performances.

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid7’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

On June 22nd, Raymond went on a day trip near the border with Thailand. He took his last breath the next morning; a medical examination suggests he passed away due to gastrointestinal issues. While no further details surrounding Raymond’s death have been released, Kyar Pauk tells IndieLand he feels the coup and events that followed spurred his friend’s untimely passing.

Kyar Pauk, who became friends with Raymond when they were young and whose father made music with Raymond’s father, has been grieving since Raymond’s death. “He was one of the best producers, singers, songwriters and possibly the most beautiful soul in the industry,” he says, adding that Raymond’s way of creating original music inspired other young musicians. “The way he composed songs was so grand and complex and his lyrical and melodic twists and everything were so beautiful,” he tells IndieLand.

Novem Htoo holds the hand of Raymond at his funeral.

Novem Htoo

When the coup happened, it killed Myanmar’s rock scene. “The music movement is now zero in Myanmar. Nobody is recording anything,” says Kyar Pauk.

Having spent decades making music under military rule, audio engineer and producer Myint Zaw said he no longer feels good to be alive. “I feel lost for the future of music here, as creation has run away,” he tells IndieLand.

Songwriter and producer Shwe Gyaw Gyaw also says he has no motivation to create music. “Everyone is obsessed with the funeral situation of the country, mourning the losses, bracing the situation and trying to pass through,” he tells IndieLand. “We lost our life meaning and future.”

The military has acted swiftly to cut off connectivity and access to information, and digital surveillance is also rising. For Kyar Pauk, the changes highlight an inevitable course under military rule. “They do whatever they can to control the spread of good ideas that will provoke any kind of thinking,” he says. “Gradually and eventually, they will control everything.”

On May 20th, Kyar Pauk announced he was going on hiatus from the music industry. “I decided I won’t be able to make music again with this kind of mindset. Everyone is internally jailed, in prison. I don’t want to train my mind again; I don’t want to train my brain to be able to write under censorship again,” he says. Haunted by images of violence and preoccupied by concern for his loved ones, he also has no motivation. “We cannot talk about the creative level. It’s about the basic level … I cannot create.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid8’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});

Instead, he is hiding in an undisclosed location outside of Myanmar, where he is making podcasts seeking to reverse the junta’s propaganda and drawing comics for D-Day, an anti-coup online journal.

He hopes that brave artists from the next generation will eventually find ways to safely carry the flame. “I [once] strongly believed I could outsmart the censorship board. … Lyrically and educationally, I was way better than them, so some words I put into the songs were very profound and my fans got it, but [the censorship board] didn’t. I had that kind of confidence in me. I want the new artists to have that,” he says.

As news of Raymond’s death spread, fans and friends across the country erupted in grief over social media for an artist who lost his life while standing with the people in their fight for their rights.

Fearing military surveillance, Raymond’s family was unable to hold an open funeral, but on June 25th, around 300 people gathered at a rural cemetery to pay tribute to an artist whose life, many believe, was cut short as a result of the coup. In a final farewell before Raymond’s body was cremated, Novem Htoo clasped his hand. “We were together as best friends, and now I don’t know what to do anymore,” he says.

With a public funeral impossible, he has since initiated a tree-planting campaign so that fans around the country can memorialize Raymond and symbolically help his soul rest in peace.

According to Shwe Gyaw Gyaw, Raymond’s death represents a microcosm of the tragedies that have befallen Myanmar’s youth, and dealt a heavy blow to the morale of musicians across the country. “It’s very miserable to accept his death during this crisis, while he was doing what he believed in,” he says.

The coup, and Raymond’s death, crushed Novem Htoo’s morale. “I haven’t been able to mourn properly as I have to keep moving from place to place,” he says. But he vowed to continue fighting in the people’s revolution against dictatorship. “I will keep trying to make revolutionary songs … to keep expressing, to rebel through music,” he says. “Our lives got dark, yet our resilience will lighten the next generation.”

blogherads.adq.push(function () {

blogherads

.defineSlot( ‘medrec’, ‘gpt-dsk-tab-inbodyX-uid9’ )

.setTargeting( ‘pos’, [“mid”,”mid-articleX”,”in-articleX”,”mid-article”] )

.setSubAdUnitPath(“music//article//inbodyX”)

.addSize([[300,250],[300,251],[3,3],[620,350]])

.setLazyLoadMultiplier(2)

;

});